- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

Treating a shoulder patient can seem very complex and overbearing at times. This post from the Sports Physiotherapist helps breakdown different scapular dyskinesias to allow for easier diagnosis and treatment of shoulder pathologies. Reviewing each dyskinesia: Type 1: Shortening of the musculature that attaches to the coracoid process. In this dyskinesia, muscles are being shortened on the anterior side of the body (pec major and pec minor specifically). In the clinic, you will observe anterior scapular tilting and likely rounded forward shoulders. Treatment options include performing a pec minor release and pec minor stretching. Both of these techniques are demonstrated by Dr. E (the manual therapist), Mike Reinold, and Chris Johnson. Type 2: Weakness or poor activation of the Lower Trap and Serratus Anterior muscles. In the clinic, if you suspect a type 2 dyskinesia, you will likely see excessive internal rotation, "winging" of the medial border, and anterior scapular tilting. The original post has 6 great videos demonstrating how to elicit these muscles. Exercises that have shown great serratus anterior MVIC include serratus punch and push-up plus. For the lower trapezius performing prone Y's and prone shoulder external rotation is very beneficial. According to McCabe et al, Prone Shoulder External Rotation with the arm positioned at 90 degrees abduction elicited a 79% MVIC. Type 3: Excessive Superior Border Prominence. These patients often have hypertonicity of the upper trapezius muscle and likely have a poor Upper Trap: Lower Trap muscle firing ratio. From my personal experiences in the clinic, these individuals have excessively tight upper trap muscles, hypomobile first ribs, and complaints of cervical tightness as well. The Sports Physiotherapists recommends performing external rotation in neutral, upper trapezius/ levator scapulae stretching, and joint mobilization to the cervical, thoracic, and scapular regions. Additionally, Arlotta, Lovasco, and McLean found that the Modified Prone Cobra selectively recruited the lower trapezius muscle with relatively low upper trapezius muscle activation. The original article has great video demonstrations of how to perform each exercise. Check it out! References:

Arlotta M, Lovasco G, and McLean L. Selective Recruitment of the lower fibers of the Trapezius Muscle. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2011. 21.3: 403.410. Web. 27 Feb 2013 McCabe R, et al. Surface Electromyographic Analysis of the Lower Trapezius Muscle during exercises performed below 90 degrees of Shoulder Elevation in Healthy Subjects. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2007. 2.1: 34-43. Web. 27 Feb 2013.

6 Comments

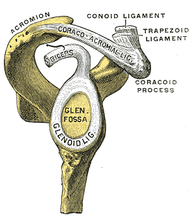

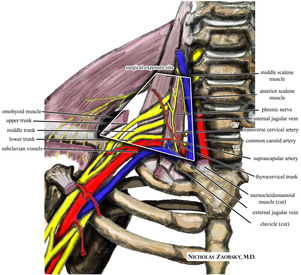

Background Information: Biceps Tendinitis encompasses a spectrum of disorders including primary biceps tendinitis, patients without primary tendinitis, and biceps tendinosis. Primary Biceps Tendinitis (5%) is inflammation of the biceps tendon in the intertubercular groove caused by mechanical stresses and overuse. Some clinicians identify biceps tendinitis simply by individuals who exhibit anterior shoulder pain that is exacerbated by shoulder and elbow flexion (Mitra et al, 2011). Mechanical stresses can include entrapment, instability, and spontaneous rupture of the long head of the biceps tendon. These patients often suffer from secondary impingement because of scapular instability, anterior capsule laxity, or posterior joint capsule tightness. Patients suffering from secondary impingement are often your younger athletic population between 18-35 years old. Primary tendinitis is much less common than those without primary tendonitis (95%). The patients without primary tendonitis have biceps tendon pathology secondary to a rotator cuff injury or labral tear. Interestingly, biceps tendinopathy is rarely found alone. It usually occurs secondary to or a cause of another pathology (Zhang et al, 2011). 85% of patients with long head of the biceps tendon partial tears have associated rotator cuff pathologies (Gazillo 2011). Additionally the umbrella term biceps tendinitis includes biceps tendinosis, which is caused by primary impingement of the shoulder and overuse. This usually involves your older population >35 years of age. Due to their age and primary impingement, these patients are also at risk for rotator cuff pathology. CLICK HERE TO CONTINUE READING  Mike Reinold is back at it again offering a different perspective on scapular exercises. It's standard procedure to include scapular strengthening with our shoulder patients. At almost any clinic, you'll see practitioners prescribing the infamous I, T, Y exercises. Reinold discusses whether or not we should be trying to achieve full symmetry, whether or not we should be performing these exercises bilaterally, and cueing our patients to "pinch your shoulder blades together." Check out his post for a different perspective along with some solutions.  There is an endless amount of shoulder tests, many lacking any diagnostic accuracy. Mike Reinold, one of the authors of The Athlete's Shoulder, presents two new tests in this article to detect SLAP lesions: the Pronated Load Test and the Resisted Supination External Rotation Test. He provides a description and video review for the tests, along with some evidence. Additionally, he links to a few other posts of his on SLAP lesions, including classification, injury mechanisms, and examination. He is in the process of developing a related post on the rehabilitation of SLAP lesions. Check out the article to add a few new tests to your tool belt! Pathophysiology: In 1980, Neer and Foster first coined the term multidirectional instability. They defined it as uncontrolled and involuntary subluxation or dislocation in the anterior or posterior direction of the shoulder. The primary pathology involved can have many potential contributors: excessive capsular redundancy, laxity due to increased elastin density and decreased collagen density, poor osseous configuration such as a flattened glenoid fossa, or weakness in the glenohumeral and scapular musculature that results in poor neuromuscular control (Andrews, Reinold, & Wilk, 2009). Understanding the primary constraints to these movements allows the clinician to have a better understanding of which ligaments and muscles are not functioning properly in MDI. There is little bony stability at the glenohumeral joint and therefore muscles and ligaments act as the primary supporter of the shoulder. Muscle activation patterns have been shown to be different in those with congenital instability compared to normal individuals; the normal force coupling that occurs is absent and the humerus has excessive translation during shoulder movements. There is some debate in the academic community about whether the abnormal muscle patterns are the cause of shoulder instability or shoulder instability leads to abnormal muscle patterns. Recent research is leaning towards the latter. The main structure resisting excessive anterior translation of the humeral head is the anterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL). Weiser et al. found that scapular protraction places increased tension on the anterior band of the IGHL. The main restraints regarding posterior instability include the posterior band of the IGHL and the posterior capsule. The rotator interval provides the main restraint against inferior instability. (The rotator interval consists of the superior glenohumeral ligament, the rotator interval capsule, the coracohumeral ligament, and the IGHL complex). One study we assessed found that subjects with MDI had significantly greater dimensions at the rotator cuff interval and inferior and posterior-inferior portions of the capsule. Additionally, inferior instability (or excessive inferior glide) was a common findings among patients with MDI. As with any other joint, the approximation of various structures can lead to injury of multiple tissue types with an injury (chronic or acute). The axillary nerve, for example, is at risk for injury with instability (the patient may present with abduction weakness). With MDI specifically, patients often present with rotator cuff tendinopathy, subacromial busitis, or secondary impingement syndrome due to the chronic nature of the pathology.

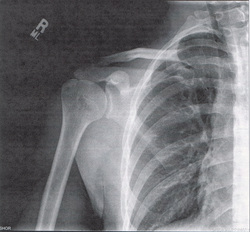

Diagnosis It is important to know the actual definition of Multiple Directional Instability in order to correctly identify individuals suffering from the disorder. There is some inconsistency in the medical field about how to accurately label these individuals. One common set of criteria include: symptomatic excessive translation of the humeral head with respect to the glenoid in more than one direction (Andrews, Reinold, & Wilk, 2009). When an individual suspect of dislocation is identified, often some form of imaging is requested by medical personnel. The initial technique is an x-ray in all common 3 views: anteroposterior, scapular, and axillary (this often doesn't reveal much in patients with MDI). Should some form of bone loss be suspected, a CT is performed to build a 3D image of the shoulder. In order to identify any soft tissue lesions, a MRI is necessary. If performed in the acute stage, a contrast may not be necessary to differentiate the tissues, but a MR arthrogram is the gold standard for viewing lesions in the shoulder related to instability. To further view a specific part of the shoulder's capsular structure, sometimes the imaging is performed in stressed positions: abducted and ER for anterior and flexed/horizontally adducted/MR for posterior. Occasionally, when nerve damage is suspected, some medical professionals prefer to perform a nerve conduction velocity test (and sometimes an MRI) to establish a baseline for nerve function and observe the progression of its healing. Imaging can also be useful in identify individuals with recurrent instability. The normal shape of the glenoid is an inverted comma. With recurrent instability, the glenoid appears like an inverted pear due to osseous destruction. It is important to identify recurrent dislocators, due to the increased incidence of additional pathologies to the shoulder (rotator cuff tears, Bankart lesions, capsular laxity, etc.). As physical therapists, we are unable to order any imaging in most settings. We have to rely on physical exam measures to determine which patients are showing signs of MDI. Patients with MDI will often present with decreased strength and proprioception, especially in the external rotators, scapular retractors, and scapular depressors. Testing ROM can give varied results, depending on the stage of the injury. In the acute stage, patients often have pain or a sense of apprehension that limit end range movement. In the chronic stage, patient may exhibit excessive ROM. As reported earlier, patients with MDI often exhibit increased instability in one specific direction compared to others; therefore, the tests for directional instability may be utilized for these individuals. To identify anterior instability and posterior instability, the examine uses the anterior and posterior instability tests respectively. To assess for inferior instability, the examiner should perform the sulcus sign. Some additional tests utilized include: Clunk test and the Load and Shift Test. Additionally, tests that identify labral pathology can be useful in determining the extent of the injury.  Conservative Treatment: Physical therapy is the first treatment course for patients with MDI. The patient should limit activities that reproduce pain or apprehension, during rehab to allow the tissues to heal. Additonally, the patient should practice proper posture, due to the stressed placed on parts of the capsule with poor posture. Conservative treatment has been shown to be effective in those suffering from MDI due to impaired muscular control or poor control and strength of the rotator cuff and scapulothoracic muscles. Patients with MDI due to bone or labral deformities have not been shown to have good outcomes with conservative treatment. Because shoulder weakness was found in 75% of MDI patients, upper extremity weight-bearing activities have been thought to play an important role in the management of MDI. In addition, rotator cuff, scapular stabilizer, and deltoid strengthening is a necessary component of the rehab program (focus on scapular stabilizers first to establish a stable base). After addressing the scapular stabilizers, the clinician should focus on strengthening the rotator cuff muscles in order to better centralize the humeral head during dynamic activities. Some clinicians prefer initiating rehab with isometric strengthening exercises or isotonic exercises in a limited range in order to allow time for the tissues to heal. Burkhead found that 80% of patients with MDI showed improvements with rotator cuff strengthening exercises. The exercises should be initiated in the scapular plane, as it is the most stable position. This position places the rotator cuff and deltoid in an optimal length-tension relationship and decreases stress placed on the anterior and posterior capsule. Exercises can be progressed to less stable positions, out of the scapular plane. Towards the end of rehabilitation, additional shoulder muscles can be addressed to further develop supporting musculature (i.e. triceps, biceps, etc.). To address the proprioception deficits, rhythmic stabilization drills can improve function of the mechanoreceptors and neuromuscular control in the shoulder by facilitating co-contraction of the shoulder musculature. Eventually, exercises should be attempted in positions of instability to decrease the muscular reflex that occurs in order to lower the likelihood of recurrent instability. Active repositioning tasks, PNF techniques, weight-bearing and plyometric exercises are also used to treat these impairments. The push-up plus, already known to strengthen the serratus anterior, has been shown to activate the subscapularis - an essential component of the rotator cuff force couple. The clinician should always remember to progress exercises in various ways: speed, intensity, frequency, etc. Stretching and PROM should not be utilized in the MDI patient due to the already excessive ROM present in the shoulder. Glenohumeral mobilizations grade III-IV should be avoided as well due to the desire to decrease capsular stress (grades I-II are permitted for pain treatment). It should be noted that conservative treatment may not be advised for all populations. According to Brotzman & Wilk, individuals < 30 years of age who experience a dislocation have a 70% chance of being recurrent dislocators. One study found that those who sought conservative treatment had a 47% recurrent dislocation rate, while those who sought surgical stabilization had a 15% recurrent dislocation rate. Therefore, patients over 30 years of age who experience a dislocation should seek conservative therapy, while patients under 30 years of age should seek surgical treatment. Always be certain of true dislocation. Often, children may present with increased apprehension for instability testing even without dislocation. Surgical Treatment If symptoms persist following a 6-12 month bout of conservative therapy, surgical treatment may be advised for the patient with MDI. Due to the overall capsular laxity, the surgical technique for unidirectional instability is not successful for patients with MDI. Capsular volume must be addressed. According to Dr. Andrews, the gold standard is the open inferior capsular shift. This technique decreases capsular volume by equilibrating capsular tension on all sides and balancing the humeral head. The approach can be anterior or posterior and is usually decided by the direction of greater instability. Those who seek surgical treatment to address instability may have an increased risk of recurrent instability of the direction opposite the approach of the procedure. The capsule can also be addressed arthroscopically (arthroscopic suture capsulorrhaphy). The advantage to the arthroscopic method is that the surgeon can identify concomitant pathologies (labral injury, rotator cuff tear, etc.) and treat them simultaneously. Thermal capsulorrhaphy is a technique that involves administering heat to the capsule with the hope of focusing on type I collagen. It breaks the cross-links and denatures the proteins, leading to a randomized state of collagen - decreasing capsular volume. This method, however, has been shown to have a high failure rate recently and is rarely used today. References:

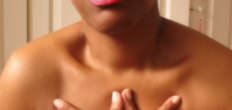

Andrews, James, Michael Reinold, Kevin Wilk. The Athlete's Shoulder. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier, 2009. 229-236, 556-559. Print. Brotzman, S., & Wilk, K. Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2003. 197-198. Print. Dalton SE, Snyder SJ. "Glenohumeral Instability." Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1989 Dec;3(3):511-34. Web. 10/21/12. Gyftopoulos S, Bencardino J, Palmer WE. "MR Imaging of the Shoulder: First Dislocation versus Chronic Instability." Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2012 Sep;16(4):286-95. Web. 10/21/12. Illyés A, Kiss J, Kiss RM. "Electromyographic analysis during pull, forward punch, elevation and overhead throw after conservative treatment or capsular shift at patient with multidirectional shoulder joint instability." J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2009 Dec;19(6):e438-47. Web. 10/22/12. Kiss, Rita. "Electromyographic analysis during pull, forward punch, elevation and overhead throw after conservative treatment or capsular shift at patient with multidirectional shoulder joint instability." Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 2009. Web. 22 Oct. 2012 Lee, Hui Jen. "Multidirectional Instability of the shoulder: rotator interval dimension and capsular laxity evaluation using MR arthrography." Skeletal Radiology. 2012. Web. 21 Oct. 2012 Ogston, Jena. "Differences in 3-Dimensional shoulder kinematics between Persons with Multidirectional Instability and Asymptomatic Controls." American Journal of Sports Medicine. 35.8 (2007): n. page. Web. 21 Oct. 2012. Swanik KA, Huxel Bliven K, Swanik CB. "Rotator-cuff muscle-recruitment strategies during shoulder rehabilitation exercises." J Sport Rehabil. 2011 Nov;20(4):471-86. Web. 10/22/12. Yamaguchi, Ken. "Management of Multidirectional Instability." Clinics in Sports Medicine. 14.4 (1995). Web. 21 Oct. 2012.  Throughout our early clinical rotations, a common impairment that we noticed was forward shoulder posture (look around your classroom and you will see it as well!). In our program, we were taught to measure muscle strength using Kendall's technique. In her book, Muscles: Testing and Function, in Posture and Pain, Kendall demonstrates measuring the length of the pec minor, along with several other muscles, in the supine position, from the posterolateral border of the acromion to the table top (>3-4 finger lengths being an adaptively shortened muscle). In this position, the biceps brachii, coracobrachialis, and pectoralis minor could all contribute to the protracted/anteriorly tilted shoulder, due to the common attachment to the coracoid process. We commonly found that the scapula lowered to normal position with shoulder flexion, which would indicate adaptively shortened coracobrachialis, even though the common assumption is the pec minor being the culprit. This article demonstrates that the pectoralis minor is indeed found to be adaptively shortened in many individuals and provides a much more reliable technique to measure the length of the pectoralis minor, as long as proper palpation skills are used. The key is to use a tape measure or caliper to measure the distance between the coracoid process and the sternal edge of the 4th rib. While there may not be sufficient evidence to start using this in the clinic right away, this new technique is something to consider when examining patients. Anatomy Review:

Pectoralis Minor Muscle: Origin: Anterior surface of the sternal ends of ribs 3-5 Insertion: Coracoid Process of the scapula Action: Protracts and depresses the scapula. Helps elevate the ribs (if O and I are reversed) Innervation: Medial Pectoral Nerve (C8-T1) Typically, External Rotation is the most limited motion in patients with adhesive capsulitis. The traditional manual therapy technique for these patients was an anterior glide mobilization to help increase external rotation ROM. This treatment was well accepted for a number of years because it agrees with the arthrokinematic principles. In recent years, there has been new evidence surfacing about the beneficial effects of posterior mobilizations for this patient population. In this article, the authors found that using a posterior glide mobilization (Kaltenborn Grade III sustained), with therapeutic ultrasound and upper extremity therapeutic exercises was the most effective for increasing external rotation ROM deficits in patients with adhesive capsulitis. They found that the posterior mobilization group had an average increase of 31.1 degrees of external rotation (after 3 treatment sessions), compared to only 3 degrees average for the anterior mobilization group. The article also found that patients with adhesive capsulitis often had a decreased rotator cuff interval space, pushing the humeral head anterior/ superior and not allowing normal posterior/ inferior motion. We must remember that at the glenohumeral joint, both anterior and posterior forces must be in coordination for proper stability. Anatomy and Kinesiology Review: |

| Superior Glenohumeral Ligament: Taut in adduction, inferior and a/p translations of the humeral head. | Middle Glenohumeral Ligament: Taut in anterior translation of the humeral head, especially in 45-60 d. of abduction; external rotation | Inferior Glenohumeral Ligament (has 3 parts): Axillary pouch: taut in 90 d. abduction, combined with a/p and inferior translations. Anterior band: taut in 90 degrees abduction and full external rotation; anterior humeral translation. Posterior band: taut in 90 d. of abduction and full internal rotation. | Coracohumeral Ligament: Taut in adduction; inferior translation of the humeral head; external rotation |

Kinesiology Reference:

Neumann, Donald. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System. 2nd Edition. Mosby Inc., 2012. Print.

Due to the multiple contributors to subacromial impingement, the treatment must be addressed in various methods. Some common impairments seen include: decreased motor control of the middle/lower traps, decreased motor control of the serratus anterior, decreased inferior accessory motion, poor scapular humeral rhythm, and of course, poor posture.

An important component for good shoulder control includes proper usage of the scapular stabilizers. Some of the muscle tend to be overused, while others are under-utilized. To determine which muscles belong to, just observe the resting position of the scapula! The press-up and push-up plus have been shown to activate both the lower trapezius and serratus anterior greater than the upper trapezius. Prone flexion, one-arm row, and prone abduction activate the lower trapezius over the serratus anterior, while shoulder press and push-up plus activate the serratus anterior over the lower trapezius. The middle trapezius is activated more than the upper trapezius with prone abduction and one-arm row.

It has been shown that exercise and home exercise programs have success in improving the symptoms of the patient, but the addition of manual therapy (i.e. mobilizations, STM) could potentially improve symptoms even more or faster. Of course scapulohumeral rhythm is of concern. Eccentric exercises of the rotator cuff have been shown to improve the patient's complaints as well.

While other shoulder injuries do not particularly fall into the category of subacromial impingement, I usually include these treatments in my plan of care for many shoulder pathologies. Any time the shoulder undergoes limited motion, the inferior capsule has a tendency to become restricted. With inferior glides, you can help prevent that! And, of course, posture is an issue with almost every individual. Poor posture=poor scapular stabilization. Retraining of the scapular stabilizers can speed up the rehabilitation of your patient.

References:

Andersen CH, Zebis MK, Saervoll C, Sundstrup E, Jakobsen MD, Sjøgaard G, Andersen LL. "Scapular muscle activity from selected strengthening exercises performed at low and high intensities." J Strength Cond Res 2012 Sep;26(9):2408-16. Web. 08/26/2012.

Başkurt Z, Başkurt F, Gelecek N, Özkan MH. "The effectiveness of scapular stabilization exercise in the patients with subacromial impingement syndrome." J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2011;24(3):173-9. Web. 08/26/2012.

Bernhardsson S, Klintberg IH, Wendt GK. "Evaluation of an exercise concept focusing on eccentric strength straining of the rotator cuff for patients with subacromial impingement syndrome." Clin Rehabil. 2011 Jan;25(1):69-78. Epub 2010 Aug 16. Web. 08/26/2012.

Camargo PR, Avila MA, Alburquerque-Sendín F, Asso NA, Hashimoto LH, Salvini TF. "Eccentric training for shoulder abductors improves pain, function and isokinetic performance in subjects with shoulder impingement syndrome: a case series." Rev Bras Fisioter 2011 Nov 21. pii: S1413-35552011005000032. Web. 08/26/2012.

Şenbursa G, Baltaci G, Atay ÖA. "The effectiveness of manual therapy in supraspinatus tendinopathy." Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2011;45(3):162-7. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2011.2385. Web. 08/26/2012.

Insider Access pages

We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!

Archives

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

October 2016

September 2016

August 2016

July 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

March 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

November 2015

October 2015

September 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

May 2015

April 2015

March 2015

February 2015

January 2015

December 2014

November 2014

October 2014

September 2014

August 2014

July 2014

June 2014

May 2014

April 2014

March 2014

February 2014

January 2014

December 2013

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

August 2013

July 2013

June 2013

May 2013

April 2013

March 2013

February 2013

January 2013

December 2012

November 2012

October 2012

September 2012

August 2012

Categories

All

Chest

Core Muscle

Elbow

Foot

Foot And Ankle

Hip

Knee

Manual Therapy

Modalities

Motivation

Neck

Neural Tension

Other

Research

Research Article

Shoulder

Sij

Spine

Sports

Therapeutic Exercise

RSS Feed

RSS Feed