- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

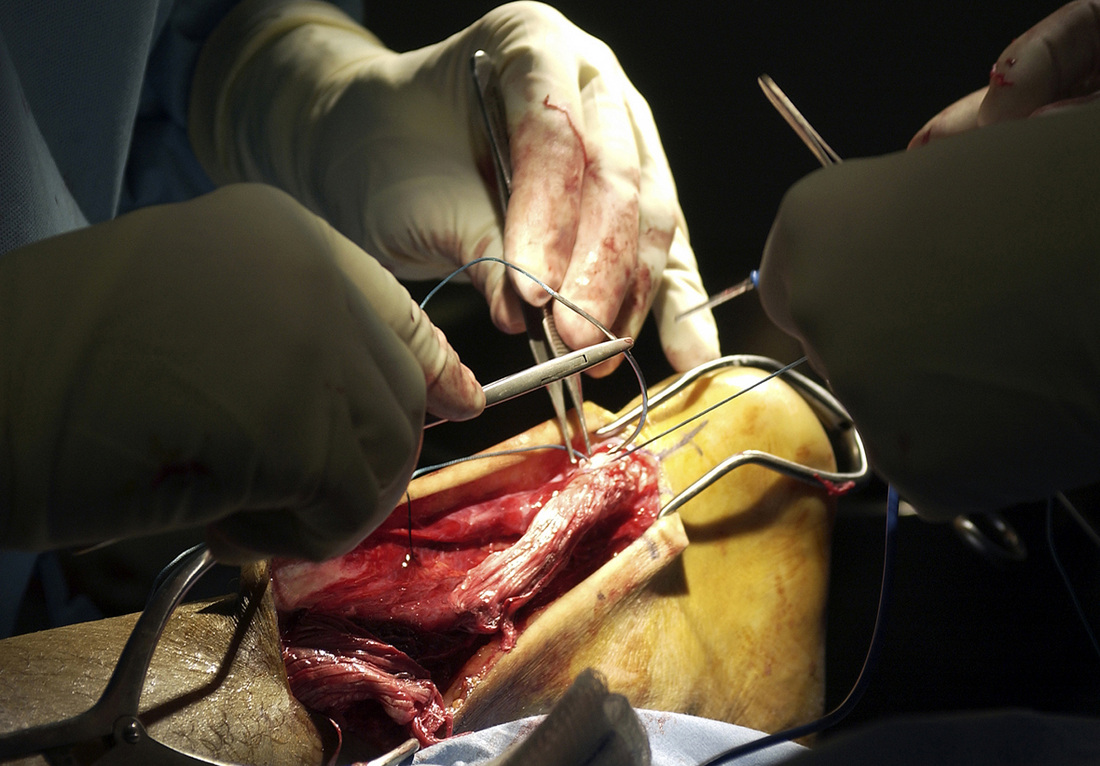

Introduction: The Achilles tendon is exposed to high levels of stress during locomotion and movement. Because high forces are transmitted through this tendon, continuous physical stresses degrade and degenerate the structural integrity of the Achilles. Ruptures are most commonly seen 2-5 cm above the calcaneal joint. The ruptures most likely occur between the 3rd and 5th decade of life and 25%-30% are seen bilaterally. Although high activity and sports are correlated with an Achilles tendon rupture, "incidence of Achilles tendon ruptures in recreationists amounts to 61% (Grubor 2012)." Decreased tendon strength, increased physical activity, past history of corticosteroids, and previous history of trauma have all been attributed to possible causes. Anatomy: According to Ding et al, the Achilles tendon is about 15 in. long and has attachments at the calcaneal tuberosity and the lower 1/3 of the calf. The tendon is vascularized and has no sheath, so the reticular tissue connects it to the aponeurosis. Three muscles contribute to the Achilles tendon: gastrocnemius, soleus, and plantaris. Origin: -Gastrocnemius: (medial head) proximal and posterior part of the medial condyle and adjacent part of the femur, capsule of the knee joint; (lateral head) lateral condyle and posterior surface of the femur, capsule of the knee joint -Soleus: posterior surfaces of the head of the fibula and proximal 1/3 of its body, soleal line and middle 1/3 of the medial border of the tibia, and tendinous arch between the tibia and fibula -Plantaris: distal part of the lateral supracondylar line of the femur, adjacent part of its popliteal surface and oblique popliteal ligament of knee joint. Insertion: -All muscles join together to form the Achilles tendon and insert into the posterior surface of the calcaneus Action: -All 3 muscles plantarflex the ankle, but the plantaris and gastrocnemius aid in flexing the knee as well Innervation: -Tibial Nerve Clinical Presentation: Patients with a ruptured Achilles tendon will complain of intense pain at the time of injury, palpable indentation in the Achilles region, and a loss of plantarflexion strength. As stated above, patients aged 30-40 years have the highest incidence with men being injured more frequently than women 5:1 (Mezzarobba, 2012). The patient will have a positive calf squeeze test, and results can be confirmed using ultrasound imaging (calf squeeze test is also known as the Thompson Test). Ultrasound has been shown to be highly sensitive and specific (Grubor 2012). Additionally, patients will perform poorly with the heel rise involved in the MMT of the plantarflexors. Surgical Management: It is a common debate whether conservative treatment or surgical management is the most effective treatment in patients with a ruptured achilles tendon. One of the primary reasons that surgical repair is often chosen over the conservative approach is the hypothesis that surgical repair reduces the likelihood of Achilles tendon re-rupture. Soroceanu et al performed a meta-analysis of RCTs and found no difference in re-rupture rate between surgical repair and non-surgical approaches, so long as early ROM was performed. No significant difference was found between the groups for calf circumference, ROM, and functional outcomes as well. If the conservative group patients did not perform early ROM, surgical repair was found to be superior. With the risks surgery places on the patient, such as infection, it is important to educate clients on all options of care. It is also important to examine the effects different surgical techniques have in order to continue developing the best plan of care for the patient. Mezzarobba et al. reviewed the results of a percutaneous repair of the Achilles tendon using Tenolig. Interestingly, the authors found several changes to the involved limb. Increased dorsiflexion ROM was noted due to lengthening of the muscle, along with calf atrophy, which leads to decreased plantarflexion strength. The quadriceps volume was found to increase as well due to the compensation resulting from calf atrophy. It is still under debate as to the effectiveness of nonoperational treatment vs. surgical management (Krapf et al., 2012). There are of course various surgical styles for the repair of an Achilles tendon: open repair vs. minimally invasive (percutaneous) repair. For awhile, it was theorized that the minimally invasive approach would decrease complications and accelerate rehabilitation; however, no significant difference was found between the two approaches (Kolodzielj et al, 2012). Additionally, it was shown that immediate weight-bearing and range of motion were necessary to improve outcomes. Lack of weight bearing led to impairments, such as muscle strength, endurance, and activity. When comparing open repair to mini-open repair for Achilles tendon rupture, a significant difference was found for start times for rehab (open repair: 37 days, mini-open repair: 19 days) and return to activity (open repair: 7 months, mini-open repair: 5 months) (Klein et al, 2012). Following surgical repair of the Achilles tendon, some patients experience a tendinopathy-like pain. The standard eccentric exercises or endoscopic Achilles tenolysis have been found to be sufficient in reducing the pain (Liu, 2013). Following surgery, the traditional model was to immobilize the limb in a cast/boot for 6-8 weeks in order to protect the healing tendon; however it was found that mobility can occur as early as 10 days following surgery and improve the apposition of the tendon (Soroceanu et al, 2012). One study looked at the effect early mobility has on open repair vs. non-surgical management. Initially, Achilles tendons that underwent open repair were found to be superior in their ability to withstand biomechanical loads compared to nonoperational approaches. These differences disappeared at 8 weeks. The conservative group was found to have greater histological characteristics and tendon lengthening. At the end of the study, no functional difference was noted between the groups. While these results may be surprising, it must be noted that the study used rats in the assessment and cannot be directly correlated with human reactions. The implications of this study must be further explored under human subjects before the results can be considered in rehabilitation principles.

References:

Ding W, Yan W, Zhu Y, Liu Z. (2012). Treatment of acute and closed Achilles tendon ruptures by minimally invasive tenocutaneous suturing. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg., 18(5):405-10. Web. 12 Jan 2012. Grubor P, Grubor M. (2012). Treatment of Achilles tendon rupture using different methods. Vojnosanit Pregl, 69.8: 663-668. Web. 22 Dec 2012. Kendall FP, McCreary EK, Provance PG, Rodgers MM, & Romani WA. (2005). Muscles: Testing and Function with Posture and Pain. (5th ed., pp. 414-415). Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Klein EE, Weil L Jr, Baker JR, Weil LS Sr, Sung W, Knight J. (2012). Retrospective Analysis of Mini-Open Repair Versus Open Repair for Acute Achilles Tendon Ruptures. Foot Ankle Spec. Web. 12 Jan 2013. Kołodziej L, Bohatyrewicz A, Kromuszczyńska J, Jezierski J, Biedroń M. (2012). Efficacy and complications of open and minimally invasive surgery in acute Achilles tendon rupture: a prospective randomised clinical study-preliminary report. Int Orthop. Web. 12 Jan 2013. Krapf D, Kaipel M, Majewski M. (2012). Structural and biomechanical characteristics after early mobilization in an Achilles tendon rupture model: operative versus nonoperative treatment. Orthopedics, 35(9):e1383-8. Web. 8 Jan 2013. Lui TH. (2013). Endoscopic Achilles Tenolysis for Management of Heel Cord Pain after Repair of Acute Rupture of Achilles Tendon. J Foot Ankle Surg., 52(1):125-7. Web. 12 Jan 2013. Mezzarobba S, Bortolato S, Giacomazzi A, Fancellu G, Marcovich R, Valentini R. (2012). Percutaneous repair of Achilles tendon ruptures with Tenolig: Quantitative analysis of postural control and gait pattern. Foot (Edinb), 22(4):303-9. Web. 8 Jan 2013. Soroceanu A, Sidhwa F, Aarabi S, Kaufman A, Glazebrook M. (2012). Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment of acute achilles tendon rupture: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 94(23):2136-43. Web. 12 Jan 2013.

4 Comments

|

Copyright © The Student Physical Therapist LLC 2023

RSS Feed

RSS Feed