- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

|

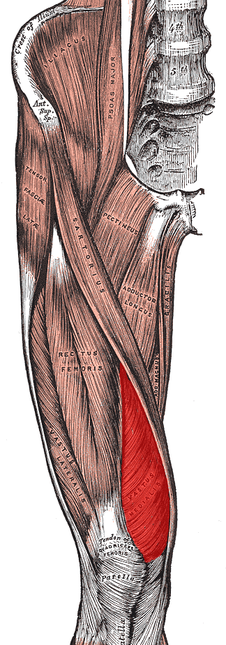

No matter where you do your rotations or practice physical therapy, you are bound to work with both people who target the VMO with their interventions and people who think it's impossible to do so. Following trauma, knee surgery, or patellofemoral pain syndrome, many practitioners claim selective atrophy and weakness of the VMO relative to the rest of the quadriceps. This becomes a focus of several interventions in the patient's care plan. Due to the controversial state of this case, we thought we would do a review on the isolation of the vastus medialis muscle. Let's start out with reviewing a little anatomy. The quadriceps is made up of four parts: rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and vastus intermedius. Rectus Femoris Origin: -Anteroinferior iliac spine (straight head), groove above rim of acetabulum (reflected head) Vastus Lateralis Origin: -Proximal part of intertrochanteric line, anterior and inferior borders of greater trochanter, lateral lip of the gluteal tuberosity, proximal half of lateral lip of linea aspera, and lateral intermuscular septum Vastus Intermedius Origin: -Anterior and lateral surfaces of the proximal 2/3 of the body of the femur, distal half of the linea aspera, and lateral intermuscular septum Vastus Medialis Origin: -Distal half of the intertrochanteric line, medial lip of the linea aspera, proximal part of the medial supracondylar line, tendons of the adductor longus and adductor magnus and medial intermuscular septum Common Insertion: -Proximal border of the patella and through the patellar ligament to the tuberosity of the tibia Common Innervation: -Femoral nerve (L2-4) Common Action: -Extends the knee (rectus femoris also flexes the hip) *(Kendall et al, 2005) One way of analyzing this controversial issue is anatomically. Hubbard et al reviewed the anatomy of cadavers to enhance the interpretation of VMO isolation. The vastus medialis is commonly broken down into two components: vastus medialis longus (VML) and vastus medialis oblique (VMO). It is thought that the VMO is responsible for medial patellar tracking, due to its oblique fiber orientation. In the study, the VMO was unable to be found separated from the VML, meaning the VMO was not found to be a muscle independently. Any attempted separation required destruction of muscle fibers. Upon review of innervation, many studies in the past have come across independent innervation, leading to the hypothesis that the VMO was a separate muscle. However, these nerves have been found to be superficial separations from the femoral nerve leading to distal motor units, sensory contribution from the saphenous nerve, or penetrating innervation for the knee capsule. The authors argue that without isolated innervation, the VMO cannot be activated independently (the patella cannot solely be pulled medially); it is the activity of the femoral nerve the stimulates the entire vastus medialis to contract and extend the knee while pulling the patella medially. Historically, many people were under the impression that the rectus femoris was the prime knee extensor. They thought the vastus medialis was responsible for the final 15 degrees of knee extension due to the inadequacies of the rectus femoris (Lieb & Perry, 1968). Boucher et al looked at the vastus medialis activity in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome. They found that the vastus medialis and vastus lateralis were not more active in terminal extension. However, they did find that in patients with PFPS, there was a decreased VM:VL ratio compared to the control group. These differences were found to be attributable to a mechanical disadvantage (greater Q-angle); when the Q-angle was decreased, the ratio returned to normal. This same difference in VM and VL ratio was found in another study to be related to mechanical factors as well (Souza & Gross, 2001). Additionally, the authors discovered that isotonic quadriceps contractions elicited larger VM:VL EMG activity compared to isometric contractions. This may influence the treatment plan for patients with pathologies, such as patellofemoral pain syndrome. Ng et al. and Cowan et al. also came across this difference in VM and VL ratio with EMG activity. In fact, the authors were able to normalize the EMG activity with use of therapeutic exercise + biofeedback. Biofeedback has been found to be a useful component in motor retraining, especially regarding earlier activation of the VMO (Cowan et al., 2002). A delay of as little as 5 ms of the VMO relative to the VL can increase the compression forces on the lateral patellafemoral joint (Boling et al, 2006). Powers described a difference between VM and VL activity as well; however, it was attributed to patellar malalignment. Decreased VM activity was not found to be the cause of abnormal patellar tracking or patellar tilt.

As it has probably become obvious, VMO isolation is a controversial issue with many conflicting studies. Thein Brody & Hall do an excellent job summarizing the research, while offering their own opinion. Regarding measuring EMG amplitude, they point out that EMG measures electrical activity, not force production. To truly assess the effects the VMO has on the patella, one must consider fiber orientation, and cross-sectional area. The authors then return back to an anatomical discussion, stating an isolated VMO contraction has never been displayed. This suggests training the VMO independently to improve timing may not be possible. In fact, VMO:VL timing has been shown to improve after training the quadriceps muscle as a whole. So what are your thoughts and what have your experiences been on this issue? Should we be spending so much time trying to isolate the VMO for rehabilitation or focus on a more general method? Let us know! References:

Boling MC, Bolgla LA, Mattacola CG, Uhl TL, Hosey RG. "Outcomes of a weight-bearing rehabilitation program for patients diagnosed with patellofemoral pain syndrome." Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006 Nov;87(11):1428-35. Boucher JP, King MA, Lefebvre R, Pépin A. "Quadriceps femoris muscle activity in patellofemoral pain syndrome." Am J Sports Med. 1992 Sep-Oct;20(5):527-32. Web. 17 Nov 2012. Brody LT & Hall CM. (2011). Therapeutic Exercise: Moving Toward Function. (3rd ed., pp. 530-531). Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Cowan SM, Bennell KL, Hodges PW, Crossley KM, McConnell J. "Delayed onset of electromyographic activity of vastus medialis obliquus relative to vastus lateralis in subjects with patellofemoral pain syndrome." Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001 Feb;82(2):183-9. Web. 26 Nov 2012. Cowan SM, Bennell KL, Crossley KM, Hodges PW, McConnell J. "Physical therapy alters recruitment of the vasti in patellofemoral pain syndrome." Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002 Dec;34(12):1879-85. Web. 26 Nov 2012. Gilleard W, McConnell J, Parsons D. "The effect of patellar taping on the onset of vastus medialis obliquus and vastus lateralis muscle activity in persons with patellofemoral pain." Phys Ther. 1998 Jan;78(1):25-32. Web. 25 Nov 2012. Hubbard JK, Sampson HW, Elledge JR. "Prevalence and morphology of the vastus medialis oblique muscle in human cadavers." Anat Rec. 1997 Sep;249(1):135-42. Web. 25 Nov 2012. Kendall F, McCreary E, Provance P, Rodgers M, & Romani W. (2005). Muscles: Testing and Function with Posture and Pain. (5th ed., p. 420). Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Lieb FJ, Perry J. "Quadriceps function. An anatomical and mechanical study using amputated limbs." J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1968 Dec;50(8):1535-48. Web. 17 Nov 2012. Ng GY, Zhang AQ, Li CK. "Biofeedback exercise improved the EMG activity ratio of the medial and lateral vasti muscles in subjects with patellofemoral pain syndrome." J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2008 Feb;18(1):128-33. Web. 17 Nov 2012. Powers CM, Landel R, Perry J. "Timing and intensity of vastus muscle activity during functional activities in subjects with and without patellofemoral pain." Phys Ther. 1996 Sep;76(9):946-55. Web. 25 Nov 2012. Powers CM. "Patellar kinematics, part I: the influence of vastus muscle activity in subjects with and without patellofemoral pain." Phys Ther. 2000 Oct;80(10):956-64. Web. 25 Nov 2012. Smith TO, Bowyer D, Dixon J, Stephenson R, Chester R, Donell ST. "Can vastus medialis oblique be preferentially activated? A systematic review of electromyographic studies." Physiother Theory Pract. 2009 Feb;25(2):69-98. Web. 25 Nov 2012. Souza DR, Gross MT. "Comparison of vastus medialis obliquus: vastus lateralis muscle integrated electromyographic ratios between healthy subjects and patients with patellofemoral pain." Phys Ther. 1991 Apr;71(4):310-6. Web. 25 Nov 2012. Stensdotter AK, Hodges P, Ohberg F, Häger-Ross C. "Quadriceps EMG in open and closed kinetic chain tasks in women with patellofemoral pain." J Mot Behav. 2007 May;39(3):194-202. Web. 26 Nov 2012.

17 Comments

Chad ICPT

11/28/2012 10:20:14 am

First off I want to thank the authors of this site for all of the work they have done. This site is really amazing and will be a very useful resource for students and young clinicians. I look forward to hearing the different ideas that are being shared at different programs.

Reply

You make an excellent point about the experience we have with our CIs. I too have been on multiple clinicals hearing the same explanations on "targeting the VMO." While I learned in school there is no point in trying to focus on the VMO, I did not have any research at the time to present to my CI. This may be a point in which we can try and share our findings with our clinical instructors!

Reply

12/5/2012 02:12:54 am

I completely agree that it is useless to focus on the VMO. That doesn't even pass face validity. I can see within session results when focusing on the ER and abductors of the hip.

Reply

Andy Vinakos

3/23/2013 10:29:42 am

This is a great little article. I've been having a chronic issue with pain on my left tibial tuberosity actually (no history of Osgood), with some other more mild pain on the patellar tendon itself. I actually want to see a different practitioner to solve my problem simply because the person I am seeing now (chiropractor of Chicago Bears/Cubs) has me doing a VMO exercise (Peterson step-up), and I was a bit surprised because I thought the whole "preferentially recruit the VMO over the VL" thing was kind of a myth and currently poo-poo in rehabilitation/the strength and conditioning world.

Reply

Thinking

6/25/2013 10:43:13 pm

Hi, thank you for your web page, it nicely put together the research. Whilst I don't preferentially activate the vmo, I think it's a shame to think adductors should not also be strengthened. As we know the vmo had connections into the addict it's, and if a ball is big enough, it will not cause internal rotation of the femur. I have this knee issue myself and know that hip strengthening on its own is not enough. In my opinion the key is progressive loading with variety of speed, range and planes, allowing for muscle and bony adaptations. Also endurance is a factor for the vmo and the patient needs to know how to evaluate this, as training when it has switched from fatigue is probably counter productive.

Reply

Paul

10/13/2013 08:33:53 pm

I had a maltracking patella problem for many years, I was walking in pain. The turn around in my injury was a rehab involving McConnell taping, VMO and glute strengthening. At first I found it very difficult to isolate the VMO, almost impossible. Although, with the knee taping the VMO:VL ratio went from 1:10 to 1:1, and I believe that this resulted in the VMO and glute strengthening exercise to be more pain free and effective. I am now running marathons. So I would be a little cautious in ruling out VMO based rehab out as a myth. I am an advocate of McConnell knee taping, VMO and glute strengthening.

Reply

10/13/2013 09:49:46 pm

Thanks for the story Paul. Mini case reports like this remind me everyone is different and that what may be inneffective for one may be effective for another. I still think we shouldn't start with the VMO because the evidence is less strong than for hips, but that doesn't mean I should never go there.

Reply

SKAY

5/25/2014 10:13:28 pm

Paul, I'm 27 and I have been struggling with this patella mistracking issue for the past 9 years. Now it led to chondromalacia patella. Could you please tell me what excercises you have been doing for VMO strengthening?

Reply

Diane

8/20/2015 02:26:26 am

Paul could you tell me what helped you to be able to isolate the VMO?

Reply

SamPT

7/1/2014 07:38:52 pm

Selective VMO training is surely a weak treatment programme for PFPS - anything that puts emphasis on one aspect of movement is not going to be as successful as teaching the correct way to complete the WHOLE movement.

Reply

William

1/28/2015 11:34:41 pm

How can you possibly selectively (by itself) "activate" (volitionally contract) a muscle area (VMO) apart from the rest of the muscle body (vestus medals) and apart from the other quad muscles when they are all innervated by a common nerve (femoral). If there is an action potential in the femoral nerve all of the muscles making up the quad complex will be "activated". AND at the very least there is absolutely no way to specifically "recruit" the VMO (oblique portion of the vastus medialis) apart from the entire vastus medialis muscle.

Reply

David

11/8/2015 01:58:55 pm

Excellent point William. Even if the atrophy was present, the literature is not very kind to the ability to preferentially activate this musculature either.

Reply

Ryan M, SPT

5/19/2019 10:17:27 am

Currently on my first solo clinical experience and have witnessed the VMO targeting exercises for patients with PFPS as well as post TKA treatment. I've primarily witnessed straight leg raises in supine with femoral external rotation to preferentially target the VMO. Considering the research presented in my program and in this article I would argue that this is shifting the exercise from quad-dominant to adductor dominant, any thoughts?

Reply

Pat Solomon

6/17/2022 12:34:02 pm

Thought I needed another TKR but the problem is the patella. Looking for help without a patellar prosthesis

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed