- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

While studying for the Orthopedic Clinical Specialty (OCS) examination, I received several emails regarding preparation for the exam. Since there is so much content to be learned and only a little organized test prep material, there lies a gray area regarding the most important concepts. Personally, the majority of my studying included the APTA's Current Concepts, the Orthopedic Physical Therapy Secrets Textbook, and reviewing Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs). Each piece of information provided different value which is why I recommend studying from several different sources. The Current Concepts is a series sponsored by the APTA which include a joint-by-joint breakdown of the anatomy, arthrokinematics, pathology, treatment, and sample questions at the end of each section. They are written by an expert on the subject matter and highlight many key components of the exam. A downside of the Current Concepts is that the material is usually written only by a single author so the material included can be limited to what that author views as pertinent. Additionally, the information in the Current Concepts may be outdated compared to the newest literature, which is why reviewing the JOSPT's in the last couple years may prove beneficial, especially regarding any landmark studies. Finally the information contained within these pages is typically pathoanatomically based and treatment follows the same model. The Ortho Secrets book was a great quick reference as well. Several times I found myself reading through Current Concepts and wanting deeper knowledge of a specific pathology. The Secrets book gave me the extra knowledge in a concise format without any 'fluff' material. The book consists of questions and answers regarding commonly misconceived PT questions. Finally, studying the CPGs was essential. The purpose of the OCS exam is to assess your knowledge of clinical practice based on the best available evidence. The Clinical Practice Guidelines are a large part of the examination because the information is the highest available evidence peer reviewed by experts. However, the CPGs are only updated every 5 years and may be outdated as well, but for the purpose of the exam, they are the gold standard. In conclusion, studying for the OCS can be challenging. There is limited availability to practice exams and much physical therapy literature is varied making it difficult to comprehend what is 'best' to know. I also utilized an online lecture series for review, so any class specific for OCS preparation may prove useful. Additionally, much of the content follows a pathoanatomical model and does not incorporate much of the various schools of thought such as MDT and movement impairment syndromes. Studying for the OCS was valuable because I gained extensive knowledge regarding the anatomy and arthrokinematics, but the information I learned regarding assessment and treatment was quite varied from true clinical practice. I hope these tips help, Jim

10 Comments

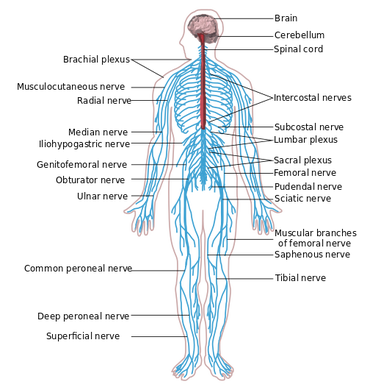

I recently had my second fellowship class which focused on joint manipulation and adverse neural tissue tension. As you may have noticed with the recent increase in posts related to the neural system, the class had quite an impact on me. The obvious benefit the manipulation portion of the course was a dramatic improvement in our technique and clinical reasoning behind when and where to do a manipulation. As beneficial as that was, the part of the course focusing on neural tension had an even greater impact. Adverse Neural Tissue Tension can be defined as: "an abnormal physiological and/or mechanical response from the nervous system that limits its normal range of motion or stretch capabilities." Due to the connections of the central and peripheral nervous systems, tests like the Slump Test and other neural tensioning exam measures can be used to identify dysfunctional neural pathways. These connections can become problematic as tension in the peripheral nervous system can be transmitted to the central nervous system as the perineum transfers tension to the spinal dura matter. Think about how a Straight Leg Raise Test works. The tension in the sciatic nerve is transferred to the lumbar spine due elevation of the leg. The systems are linked both physically and electrically. Blood supply is essential for normal nerve function and to allow the electrical signals to be transmitted. Normal neural function can be affected by compression, stretch, friction, and disease. Double crush syndrome occurs when injury occurs to one area of a nerve due to being at elevated risk secondary to an injury to another part of the same nerve/spinal segments. Normal neural flow is disrupted as pressure increases or blood flow decreases. The greater the pressure, the quicker the axonal flow is slowed. For example, pressure at 20 mmHg begins to affect nerve conduction after 8 hours while pressure at 30 mmHg takes only 2 hours. The effects of this pressure are reversible, but often take prolonged periods of relief. Pressure of 400 mmHg for 2 hours takes 1 week to recover. It is the accumulation of the slowing of a nerve at different points that truly defines double crush syndrome as may with diagnoses such as carpal tunnel syndrome also have dysfunction in the cervical spine. The patient may present with primary complaints of pain in the distal nerves, but the inclusion of a history of proximal pain or injury may be the key to returning to 100%. Next time you have a patient with "lateral epicondylitis," check for radial nerve tension and investigate the neck for any dysfunction as well.

So how do we determine if the nervous system is involved? Nerves typically have a rather vague presentation. Musculoskeletal complaints, on the other hand, tend to present with a more isolated area being affected. Some of the keys things I were taught to assess for in our class included palpation/tensioning of nerves and spinal mobility assessment. When your patient is describing their area of pain, consider what nerves typically are responsible for sensation in the area. I recognize that the graphs of nerve layouts only represent the most common presentation (~30% of the population), so we must rely on palpation of the nerves to assist us (TSPT Premium Channel members can expect videos of how to palpate the nerves in the LE's in a few weeks!). In general, the nerve diagrams can help us with those vague complaints of pain. A nerve that shows signs of irritation will be tender to palpation and present with positive findings on neural tensioning. During a neural tension test, if pain is increased with palpation, that increases the likelihood of contribution to the patient's complaints. Finally, any time you find signs of nerve pain, it is recommend you examine the spine thoroughly. Look for segmental restrictions and pain with segmental mobility testing. It may present with something as simple as being "tender," but being tender is not normal. Based on your findings in the spine, treat accordingly (improve motion is restricted areas and control motion in hypermobile areas). As always assess, treat, and reassess. We should be able to make pretty rapid gains in our patients with neural tension unless that are showing signs of central sensitization. -Chris  This past weekend, I was fortunate to take my first class in the fellowship at Manual Therapy Institute, starting half-way through the program (due to having completed an APTA-credentialed orthopaedic residency). The first lecture in the fellowship portion is Medical Exercise Therapy. I had been told previously that this was one of the less exciting classes due to the obvious lack of manual therapy involvement, but that didn't mean it was any less important. Each day, we spent approximately 2-3 hours just reviewing old material and practicing skill. As with any skill, the key to developing better motor control is practice, practice, and more practice. Being able to consistently utilize the instructors with your assessments is incredibly beneficial. The real focus of the class, however, is on exercise prescription and dosage. Most of the first day is spent discussing exercise physiology and its relation to each tissue type. While it may seem trivial to some, think about how often you either see (or prescribe) "3 sets of 10." How often is this actually what is appropriate? If the exercise is for actual muscle strengthening and you actually prescribe the "3 sets of 10" based on comparison to a 1 Repetition Maximum, that may be accurate. However, if the focus of the exercise is more so for tendon, bone, or cartilage healing, 3 sets of 10 would be way off. There was a significant focus on discussing exercise to rest ratio's and exercise dosage based on tissue type and the relation to research. The second day of the class was focused primarily on exercise prescription. We didn't review so much the different types of exercise, but more so different way to modify exercise. For example, there is an emphasis in the MTI program of unloading an overused joint in order to allow healing to occur. This includes using a lumbar unloader for treadmill walking (fowards, backwards, sideways) or a cervical unloader for the BUE, and cervical stabilization exercises. These are some of the more common ones, but we were also taught how to incorporate the idea of unloading to extremity exercises as well. For example, tissues like cartilage in the knee heal best at 20% body weight with thousands of repetitions. The treatment can be riding a bike or using a shuttle squat for 20 minutes. Of course you want to focus on other impairments that are involved with the movement impairment syndrome that lead to the injury, but you want to address the tissue as well. Given some of the recent research around imaging and having recently read Explain Pain, I recognize there is a lack of consistent correlation between what imaging and tissue pathology reveal in relation to the patient's perception of "pain." What we perceive as pain is more associated with a hyperactive nervous system, which may or may not be appropriate given the presence of true tissue injury. With MTI's emphasis on Sahrmann's movement impairment syndromes, exercise prescription is designed to eliminate abnormal movement impairment syndromes and be performed in a pain-free range. Given my success utilizing repeated motions in my treatments (thanks to instruction provided by The Manual Therapist), I questioned the concern about repetitive microtrauma as the basis for Sahrmann's technique. I was pleasantly surprised by the instructor's response to my questions. He was aware that there is definite success with repeated motions, but he is resistant towards prescribing them himself due to fear of contributing to repetitive microtrauma that may lead to worse long-term outcomes. My surprise was that he acknowledged there is no evidence that supports his concerns, but that he holds to it based on his preferred practice pattern of utilizing the Sahrmann approach. I again recognized some awareness of the possible benefit of what some may perceive as "abnormal" practices for a manual therapist. Many clinicians, especially academians, may state there is no point in doing soft tissue work to the ITB since it is not muscular. As part of my IASTM training, we are taught that engagement of soft tissue can engage the nervous system to alter tissue mobility and pain perception. This is an effect the instructor recognized specifically. You will find many advocates of a specific school of thought to be extremely stubborn regarding any conflicting idea. It is refreshing to take a course by an instructor who is always open to differing approaches. I am already looking forward to starting my mentoring hours next month and taking my next class in November. -Chris  With the completion of the USC residency graduation and reception this past Thursday night, my time in USC's Sports Residency has come to a close. Now that residency has ended I can confidently say that it was the best decision I could have made. Residency has not only had an impact on me professionally, but personally as well. The person and clinician you become when you complete such a demanding year is truly life changing. My skills as a clinician both from a clinical reasoning and manual therapy viewpoint are very much improved. I think the biggest thing that I have taken away is my way of reasoning. Even now, as I have started my new job, my mentors comments are still running through my mind with each of my patients. I critically assess my patients and my fellow co-workers patients and their treatments. I ask myself why they did this and run off 10-15 reasons why a patient might move this way or that. When my athletes come to me for an evaluation I am thinking weeks and months down the road to where I think they should be and what ideally should happen. I can recognize certain patterns much better and more importantly have a huge toolbox worth of treatments to correct impairments. Published below in a slideshow are some of the highlights of my sports residency. I post them for you all to see to understand some of the things USC's sports residency has to offer. USC's approach is very biomechanical in nature while also teaching the other schools of thought with no allegiance to one approach. This is what was so attractive about the residency experience. Furthermore, the incredible network of physical therapists and educators has been absolutely astonishing. I feel very fortunate to be part of this network and to have spoken with so many great clinicians. For those of you who are leaning towards pursuing a residency in sports physical therapy, I encourage you to make the sacrifice and further your career. I hope you consider USC's residency but more importantly, keep an open mind to all of them so that you can find the best fit for you. For me, I will now begin my next job at a private practice specializing in 1on1 treatment for collegiate/professional athletes and clientele from Beverly Hills, Hollywood, Santa Monica, and Brentwood. -Brian  Well I have officially completed my orthopaedic residency as of last week. I came out of school feeling very confident in my skills as a new graduate. I thought I was a step ahead with all the readings leading up to the residency start date. Upon retrospect, it's hard to describe how far I've come in the last year and how little I actually knew in the beginning. I cannot imagine treating patients using the methods I used a year ago. Each aspect of my residency and additional education has culminated in a better understanding of how to manage orthopaedic injuries. While it would be ideal for everyone to pursue a residency in my mind, I hope to at least provide an outline for clinical advancement by gaining additional education and training in various areas. I have said many times before that one of my favorite aspects of the SHC residency is the multiple perspectives offered. With the Orthopaedic Section's monographs of the APTA, Sahrmann's Movement Impairment Syndromes, and lectures from a manual perspective by a FAAOMPT, we learn various methods of managing our patient's injuries. The monographs offer a summary of the more current research in regards to diagnosing and treating injuries at each joint. Unfortunately, some of the information is outdated and the monograph approach of focusing on pathological tissue is as well. However, this is something that is beneficial to be aware of as parts of the OCSE is based off it and may still be useful in patient care. The Sahrmann approach allows the clinician to categorize patients by different movement patterns that led to the injury. A therapist can become extremely successful just practicing these techniques. Finally, the manual approach was a huge draw to me as I believe manual therapy can accelerate the rehabilitation in many cases. It also allows a head start in a manual therapy fellowship. One of the prime components of a residency is mentoring. While some jobs may state that mentoring is offered, it is required in residencies. Being able to utilize and learn from the clinical reasoning of a seasoned clinician with advanced training allows you to make connections that many require several years of practice to achieve. This coupled with lectures by experts in their field ensures high-level education. There obviously was much more involved with the residency, but I wanted to focus on the educational aspect. As stated earlier, I have changed completely as a clinician from where the year began to where it has ended. While much of what I have learned was part of the residency, much has also come from outside that (IASTM, SFMA, following online blogs, etc.). While I feel a residency would be beneficial for any individual looking to advance their skills in a specific area, taking the appropriate courses or using the correct resources can do wonders as well. Do not simply try to get some quick CEU's to maintain your license. With each class you take, have a deliberate plan set for how you hope to grow as a clinician (not that something can't be learned in any course). For example, SFMA or McKenzie may allow you to improve your diagnostic and treatment skills by placing into appropriate categories and prioritizing your treatments. A manual therapy certification course, may enhance your hands-on skills with a specific school of thought. Reading a book like "Explain Pain" may allow you to develop a better understanding in different areas (this one being pain science and chronic pain management). Regardless of the method chosen, I hope you all begin to develop a plan for your education and development. As for me, I will be working at Foothills Sports Medicine Physical Therapy in Scottsdale, AZ. I will begin my classes and mentoring in the Manual Therapy Institute's manual therapy fellowship in September and I hope to keep you all updated with some exciting new techniques I learn. -Chris  At the Harris Health system we only see a small percentage of pediatric cases so our clinical experiences are limited in this area. To compensate for the lack of clinical hours, our residency director, Dana Tew, PT, DPT, FAAOMPT organized a lecture with a local pediatric orthopedic expert. In this post, I want to summarize a few key points regarding pediatric- especially sport related- injuries and management. 1. If a child presents to your clinic with pain near the bone, you should almost always order an X-ray. Since muscles attach at or near the apophysis (growth plate) it is easy to see how repetitive stresses to the muscle can create undue forces across growth plate. Combined with rapid growth, adolescents are at risk for apophysitis. Apophysitis commonly occurs at the knee (Osgood Schlatter Disease), heel (Sever Disease) and medial elbow (little league elbow). Since the apophysis is skeletally immature, this area is a common site for avulsion fractures as well. The patient will likely present similar to a tendinosis patient. They will have pain near the muscle insertion and describe their symptoms as achy or throbbing. Due to the osseous immaturity, obtaining films is necessary to rule out a fracture or apophyseal injury. 2. Pediatric patients can have muscle shortness AND joint hypermobility. This is an important concept when choosing appropriate treatment options in the pediatric population. For example, a young thrower may have short Lats and Pectoralis muscles, but the glenohumeral joint is hypermobile. Many times people assume muscle shortness coincides with joint hypomobility. This may be true in older adult joints where arthritis and synovial changes have occurred, but not always the case in children. When performing a pediatric evaluation, be sure to perform a thorough joint assessment in addition to checking muscle length. 3. Parents are equally competitive about their child's athletic career as the child. Every parent dreams there child will become the next Lebron James or Aaron Rodgers, so missing this weekends little league tournament seems out of the question. It sounds ridiculous, but it is not far from the truth. Parents and children alike need education regarding tissue healing following an injury, return to sport, the importance of playing multiple sports throughout the year to avoid overuse injuries. 4. As a population, we need to do a better job preventing pediatric injuries from (re)occurring. In today's society, we have the knowledge to know what stresses will cause injury to a child. We know that factors such as pitch count, dehydration, the psychological effects of being in a sport are extremely important. However, this information is not being relayed to coaches, trainers, and parents. Despite the abundance of knowledge, rates of injury are increasing among young athletes. A recent article from Advances in Pediatrics states "the incidence of medial epicondyle apophysitis is increasing as the number and intensity of organized youth sports have increased (Hoang 2012)." As healthcare professionals specializing in movement and exercise prescription, we need to be taking a more firm approach regarding prevention, management, and discharge criteria of pediatric injuries. -Jim References:

Hoang, Quynh B., and Mohammed Mortazavi. "Pediatric Overuse Injuries in Sports." Advances in Pediatrics 59.1 (2012): 359-83. Web. USC Sports Residency Update: Learning to assess your weaknesses and learning the value of experience6/21/2014  As this incredible experience in USC's sports residency is coming to a close in a little over one month from now, I've done much reflecting lately. One year ago I was graduating from PT school and today I am treating high school, college, and professional athletes. A lot has changed from a personal and professional perspective. Going into the sports residency I had many expectations and opinions on what I thought I would get out of it. What I envisioned was much different then what has truly transpired. The most important thing I have learned this year is to constantly assess, reflect, and expand on each and every patient case. Whats the pain generating structure? What is contributing to that? Whats the most important contributing structure? How did you verify one vs the other? What treatment intervention will you choose and is that the most appropriate/best intervention and why? How did you measure if there was a change? Are you reassessing every session? Are you making a change every session? If your patient is not progressing have you expended every possible reason why? These are the daily thoughts I am challenged to think about with every patient. The residency has flipped my thought process completely. School gave me a very basic foundation, but it couldn't give me the clinical reasoning development that a residency could. It's not just clinical reasoning though, its manual therapy skills as well. Is my body placement the MOST optimal? Am I being lazy and not using a belt to get the perfect stabilization? Am I using a wedge under the scapula for shoulder mobs? Am I measuring well? Is the manual therapy selection (assessment or intervention) the very best I can use right now for this patient? Why? What makes it the most appropriate? Lastly, I think what is often confused is the word "experience". Just because someone has years of experience does not mean that experience has been "good" experience. On the flip side, just because one goes though a residency and gains additional experiences doesn't mean they are better than someone five years out. I hear that all the time, a residency gets you five years of experience in one year. Well, thats not necessarily true. The intention is to advance your experience in a particular subspecialty faster and more focused than a non-resident, thats all. Every person will be different. Do I have more experience treating athletes that I would have in an outpatient orthopedic group? Yes, thats without a doubt. Training room at the high school, college, and professional level every week, clinic time with weekend warriors, high school, college and professional athletes, and observation/co-treating with mentors in the clinic, USC, and private practices has given me opportunities that I wouldn't have been able to replicate without the residency. The point is that whatever your experience is, make the most of it. If you feel like you're weak in one area go out and find a way to improve that area. There are manual therapy courses and fellowships, sports physical therapy conferences (TCC), residencies and fellowships, online blogs and webinars, and more. Follow the top PT's in the area you want to be in and pay attention to what they are following, conferences they are going too, and places they have worked. Take advantage of the situation you have and keep moving forward! - Brian  Last week, PT Think Tank put up a post about how clinic owners view residency grads and incorporate the added training into their job offers. This was an excellent topic to present as many do not consider potential employers' opinions when deciding on whether or not to pursue a residency. While the interest in residencies appears to be increasing from a new grad perspective, many employers continue to be unaware of the benefits of a residency or why one would actually consider pursuing one. What many do not realize is that we graduate physical therapy school as generalists. We know a little bit about many different areas, but are in no way experts in any specific area. That doesn't mean we graduate incompetent, but we definitely have an inexperienced aspect to our care. While many are aware that residencies contain many different components such as additional didactic/clinical work, mentoring hours, etc., they are unaware of the impact this plays on the "experience" of a PT. A residency allows one to gain specialized training in one specific area. This immediately separates the typical "new grad" from a "residency grad," or even a PT 1 year out of school. A residency basically allows you to accumulate the experience at a higher rate compared to just regular practice. This is possible because of the accelerated development of clinical reasoning. That is not to say that a residency is necessary. I know plenty of individuals who are driven sufficiently to become an expert clinician where that residency is not required...but it doesn't hurt. I was asked in an interview why the employer should hire me (1 year out of PT school and a residency graduate) instead of a clinician with 10 years experience. I simply explained just because a PT has been practicing for a decade, it doesn't mean they are any more competent than a new grad. We know plenty of 10-year PT's who still use ultrasound and hot packs regularly. Sometimes years of practice does not correlate with improved clinical skills rather more time to form improper habits. As a residency graduate, one must be careful of potential employers and their value of residency training. If an employer does not understand the value of having highly trained clinicians on staff, that says quite a few things about the philosophy of that work place. A clinic that is looking to hire any warm body has no interest in providing quality care. With skilled clinicians, patients will have improved outcomes, resulting in word of mouth referrals and desired care. My mentor is one of the few Fellows of Manual Therapy in the state and repeatedly has referrals specifically directed towards him. This is becoming increasingly important as health care is moving towards a quality/outcomes driven reimbursement model. Should a residency grad have increased pay? Absolutely. Most clinics pay based on experience, not skill. This is unfortunate as there are just as easily bad "experienced" clinicians that have been doing the same thing for 20 years as there are bad new grads. Experience does not guarantee quality. The way I approached this topic in interviews was I listed the average salary for PT's in my area. I then gave a number above that as I felt a residency program develops above-average PT's, justifying the above-average pay. Depending on the setting you are looking to practice, you will have a various amount of influence in this area. Some settings have so many qualified applicants that you may have little bargaining power. In other places, you will have a big say due to your added training. In summary, you are going to hear a variety of opinions in regards to the value of residency training from clinic owners. Answers may vary from seeing residency training as a deficit to only hiring residency graduates. An employers view on residency training says a lot about what they think about continuing education and providing quality care. While you may be an "above average" clinician following residency graduation, that does not guarantee increased pay (due to supply and demand), so I would not pursue a residency for the financial reasons. However, if you are interested in growing as a clinician, a residency, fellowship, or some other advanced training program may be for you. Currently I am completing the upper quarter module at the Harris Health System orthopedic residency. After covering the shoulder and elbow, we spend the final 2-3 weeks reviewing wrist and hand conditions and management. This section of the module is taught by certified hand therapists and occupational therapists because they see the majority of distal upper extremity injuries at my clinic. During last Monday mornings lab we covered splint making. In this post I will cover the various splints we made with indications of when to utilize each splint. One key piece of information regarding splinting: splint as little as possible to maximize ROM at surrounding joints. Generally, only splint one joint proximal and one joint distal.

Splint making is not difficult, but like any other skill it does take practice. When making splints, focus on the diagnosis at hand and the specific impairments of the patient. As stated early, limit as little movement as possible. Hand-land can seem like a scary place at times, but with a little practice and anatomical review, you will find that treatment is similar to many other joints of the body.

-Jim  When selecting which residencies you want to apply to, a component some choose to consider is teaching. While I was interested in possibly teaching, I can't say it was necessarily one of my top criteria for deciding which ones to apply to. I had a preconceived idea that any teaching a resident would be doing would include the type of classes taught in the 1st year of PT school. That didn't exactly make me want to switch to the academic side of PT, especially with the thought of making lesson plans and grading paper. Upon accepting the residency position at Scottsdale Healthcare, I was completely unaware of the two teaching opportunities I have had thus far. A couple months ago, I was the clinical instructor for a student on her final rotation before graduation. This was a form of teaching I thoroughly enjoyed in that it was highly clinical-based. Going back to PT school, I never thought I would want to become a CI due to my distaste for completing the CPI. As many have said before, teaching an enthusiastic student can be incredibly rewarding. Being able to see the transition of a student to a highly competent physical therapist is pretty mind-blowing. We all know that we can learn from a student when they ask questions that challenge us, but we also learn by reinforcing what we already know when we teach them, as it further embeds the information into our minds. While it may seem unusual for a 1st year PT to be having a student (I had previously thought that new grads were not allowed to have students), the residency makes up for it in 2 ways. First, as residents we had developed a clinical reasoning and skill-set that were beyond most new grads, allowing us to further the skills of the students. Secondly, many of our mentoring hours changed format to mentoring for how to be a CI. As I said earlier, this teaching opportunity further enhanced my understanding of the residency material as well. The second opportunity for teaching was a recent cervical course that my mentor hosted in AZ. The other resident and I were TA's for the course, where we helped out in lab with teaching the various examination and treatment techniques. It was really interesting to watch these PT's learn and develop their skills as it was in a way a look back at how the other resident and I felt at the beginning of the residency. Another component of the course was that I was able to contribute to a current literature review regarding manual therapy in the cervical spine. I bring both of these teaching methods up because my initial impression of how one could teach in a residency was to give a case study or teach to 1st or 2nd year PT students. Both of the methods I was exposed to were more clinical-based in my opinion and thus more interesting to me. I hope that some reading this will perhaps be more open to contributing to the development of PT as a profession by teaching in any method. I was resistant towards it originally, but I found a path that was much more appealing to me and hopefully you will as well! -Chris |

Copyright © The Student Physical Therapist LLC 2023

RSS Feed

RSS Feed