- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

|

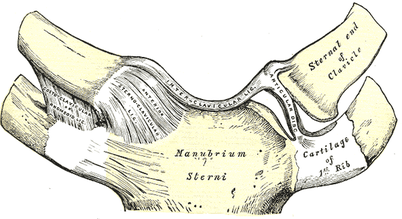

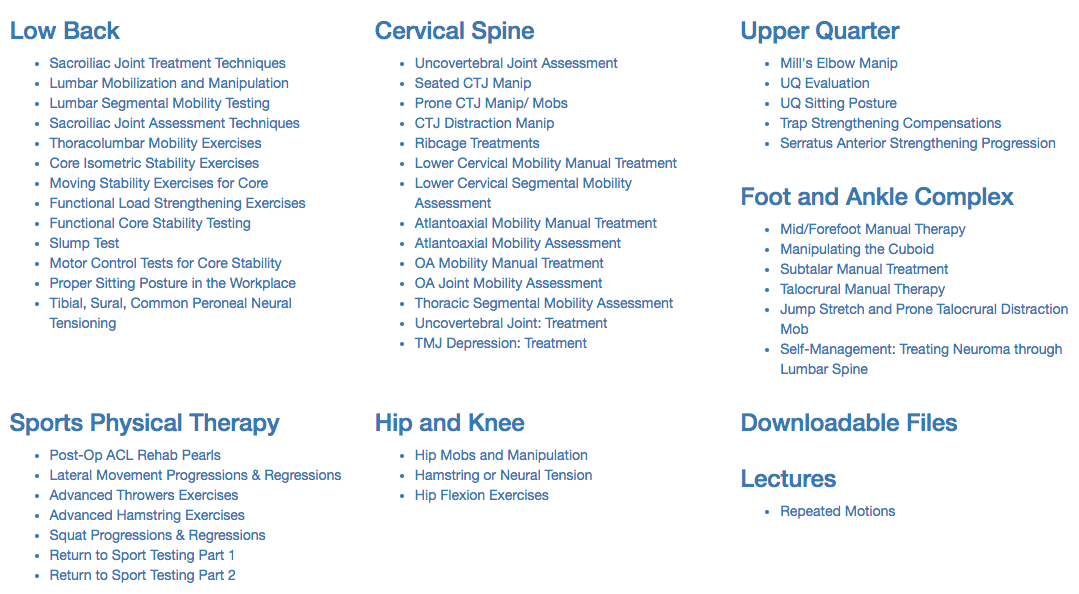

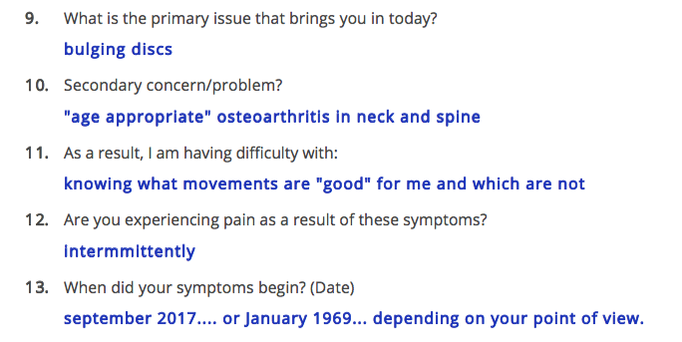

This past week I had a patient that presented with left upper quarter pain following a traction injury to her left arm as her dog yanked her arm forward. The pain was located over her left clavicular region and anterior to left scapula. My examination revealed hypomobility over her left ribs 2-3 and left sternoclavicular (SC) joint as her primary restrictions (both of which reproduced her pain when assessed). She has made excellent progress just in the treatment from the first day with joint mobilizations of the SC joint and and ribs. With reflecting upon this patient, I thought it would be great to review some of the anatomy and arthrokinematics for the SC joint. Anatomy of Sternoclavicular Joint The SC joint is made up of the medial end of the clavicle, the manubrium and an articular disc in-between. It is important to understand that the sternoclavicular joint is a saddle joint. It gets its name from the shape as it has a concave surface in one direction and convex in another, like a saddle. The medial aspect of the clavicle is concave anterior-to-posterior and convex superior-to-inferior. The manubrium has the reciprocal joint surface. The result is that with protraction/retraction, the sternum rolls and glides anteriorly and posteriorly, respectively speaking, and with elevation and depression, the clavicle rolls and slides opposite (roll superiorly and slide inferiorly with elevation; opposite for depression). Additionally, there is some posterior rotation of the clavicle that occurs with elevation and anterior rotation with extension. When it comes to assessing and treating joint restrictions in the SC joint, I try to keep it simple. Assess the mobility in each direction and mobilize into the restriction. It's possible you'll note some hypermobility in a certain direction (you don't want to increase mobility there). Often, you will note that the restricted aspect of the joint may correlate with physiological motion deficits in the shoulder; however, that is not a rule of presentation. To make matters simpler, stick with finding the restricted direction and mobilizing it. For more information on the anatomy and biomechanics of the SC joint, check out the videos below! -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

6 Comments

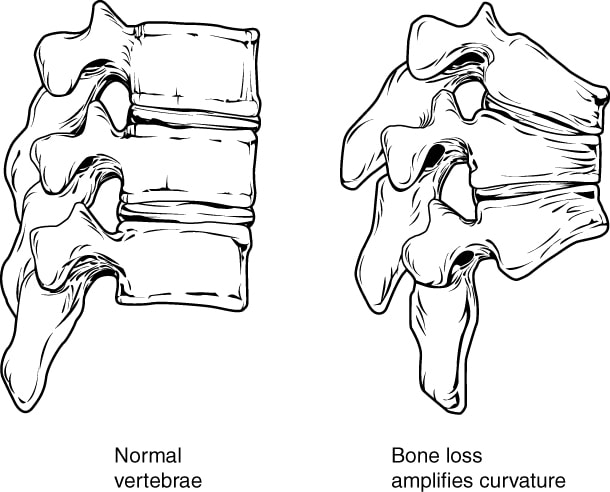

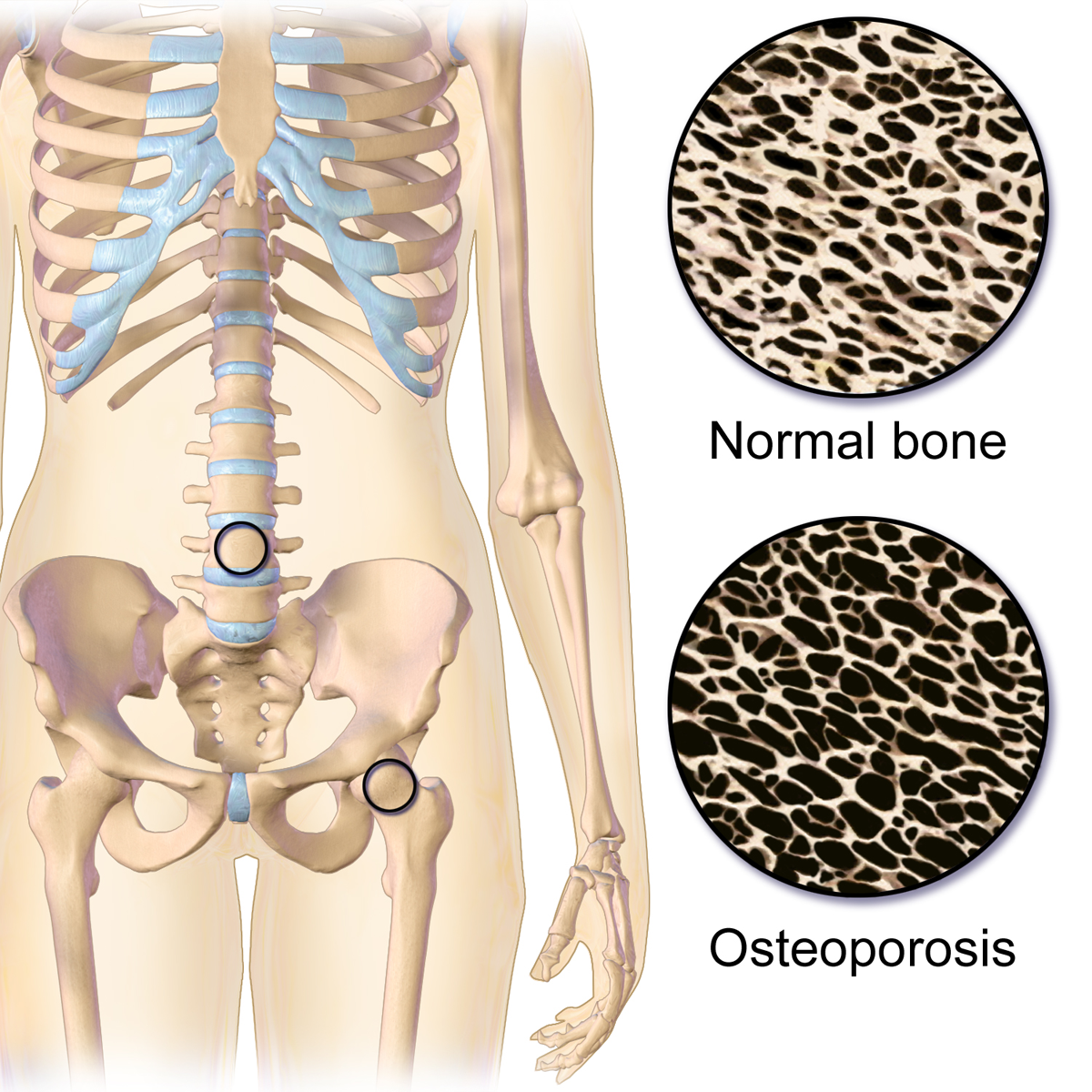

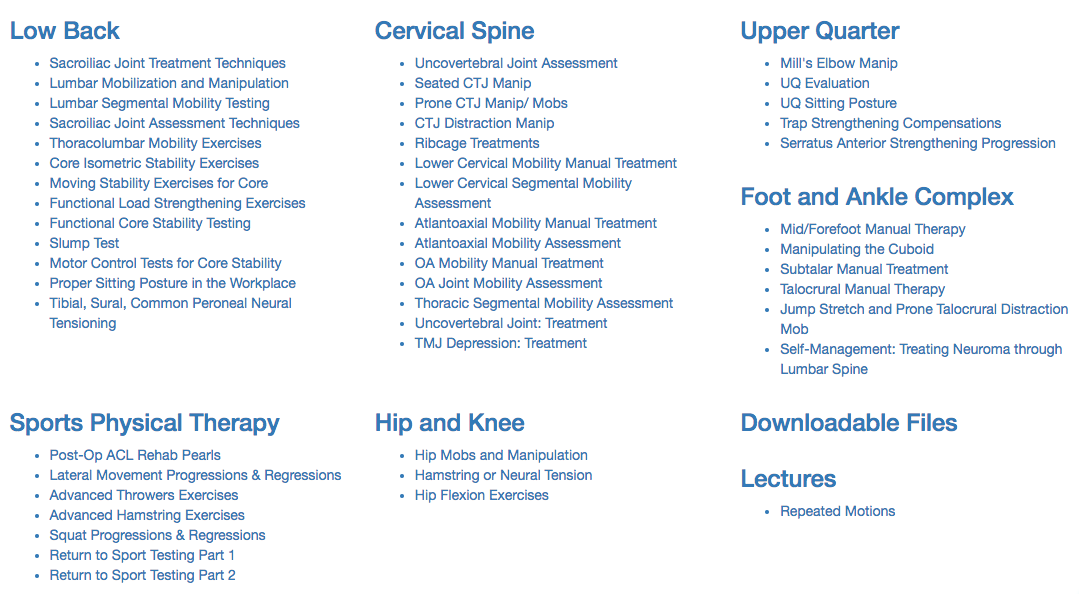

Aligning with the theme of this month, overhead athletes, today we are going to talk about the biomechanics of the tennis serve. The tennis serve is one of the most complex movements in regards to mechanics. With the amount of force required to generate power from the ground up, it is truly a movement that requires the full kinetic chain. Depending on what research you read, the tennis serve is broken down into approximately 8 stages. Stage 1- Body Positioning: The idea with this phase is to start to properly set up the body for force generation. Stage 2- Ball Release: The idea with this phase is to toss the ball at 100 degrees of abduction and just lateral from overhead. The importance of ball release positioning is that it will effect the GH positioning and how much shoulder abduction is required. While it may seem insignificant, this is one of the most important phases to prep the body for the success of the tennis serve. Stage 3- Loading: This phase is focused on building power through the legs. There are two ways athletes take on this phase.... One way is the "foot up" approach which allows greater vertical forces. For those athletes that prefer the "foot up" approach during the loading phase, they require significantly more eccentric control for the landing. For those athletes that prefer the "foot back" approach, they require increased front knee extension. Therefore, those with quadricep tendon or patellar tendon issue may struggle with this approach at times. The benefit of this approach is a wider base of support which allows for increased squat depth. Stage 4- Cocking: This phase is important for developing max potential energy before impact. Biomechanically, the shoulder and pelvis will tilt laterally, the spine will move into a hyperextension, lateral flexion, and ipsilateral rotation while the shoulder abducts 100 degrees and externally rotated with the elbow flexed and wrist extended. Quite a bit of shoulder stability is required from the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, biceps, serratus anterior, and left internal oblique (right handed hitters). Stage 5- Acceleration: This phase is important for transitioning into forward movement of the serve. Speed is dependent on the previous four stages. The internal rotators of the shoulder (pec major, lats, subscap) and the trunk muscles are the primary movers in this phase. Furthermore, there is peak activity of the gastroc and quadriceps towards the end of this phase. Stage 6- Contact: This phase determines the ball velocity which is dependent upon the amount of shoulder internal rotation and wrist flexion. Additionally, the shoulder abduction angle at contact is typically around 100 degrees, in addition to the significant lateral tilt of the trunk. Stage 7- Deceleration: Similar to the baseball throw, the deceleration phase is the most forceful due to the eccentric contraction of the post cuff, serratus, deltoid, and erector spinae muscles. Stage 8- Finish: Lastly, the finish is the braking forces of the tennis serve which requires complete stop of the movement to get ready for the next shot. This is the phase which requires the most lower extremity eccentric forces. So why is this important? Understanding biomechanics of the positions our athletes get into can help us address their specific complaints. Additionally, it helps us connect to our athletes to be able to speak the same language as them to instill confidence in our ability to understand what they do in their sport. - Brian Schwabe, PT, DPT, SCS, COMT, CSCS See more from TSPT: If you are looking to improve your clinical efficiency, a simple place to start is the intake paperwork. The intake forms often provide the patient's medical background, outcome measures, etc... AND hopefully gives a glimpse into the patient's own description of their symptoms. This is essentially a snapshot of their subjective history, which guides you into specific objective measures. In this post, I outline the power of language from the intake paperwork and my strategies to maximize my efficiency prior to EVER meeting the patient. The Power of LanguageA patient's language provides significant insight into the underlying cause of their problem. For example, if I am reviewing a new evaluation's paperwork for someone who has experienced chronic low back pain for the past 10 years, I am interested in their current thoughts about their systems. If the pain has been present for 10 years, what other interventions have they tried...? do they believe it can get better? If they perseverate on past surgeries, anatomical degeneration, their dog that passed away when they were young, and getting fired from a job 6 years ago, I can draw conclusions regarding biopsychosocial factors are influencing their low back pain. This same patient has likely uses language that reinforces their current symptomology. The language is engrained in the patient's neurology and likely includes thought viruses and f.e.a.r (false evidence appearing real). Thought Virus: “A thought virus is a negative or limiting belief. Often times, a thought virus is generalization or a misrepresentation that was once drawn from experience but is now inaccurate because of its separation from current context as well as evolution of knowledge and understanding. The danger in thought viruses is that, because they often contain some truth or they are partly true in some contexts, people are less likely to question their validity.” Heafner Health Intake QuestionsAs part of my intake paperwork at Heafner Health, I have all patients answer the questions below. With these questions, I want to know why someone is coming to see me, what activities they are unable to do, and approximately when their symptoms began. While I am looking at the objective data with each question, I am also investigating the specific language they use to describe their problem. Their answers provide insight into their perception of injury, fear avoidance to movement, and what they believe causes their issues. When someone answers the intake paperwork, I am merely trying to gather raw data that will then be confirmed or denied during the initial evaluation. Each question is a sliver of the entire pie that creates the framework of their current injury. Reviewing my questions above, here are my thoughts to the answers for a patient I treated a few weeks ago: Questions 9/10: What is the primary issue that brings you in today? This patient identifies his bulging discs as the primary issue that brings him into the clinic. Typically, when someone writes 'bulging discs,' I make a mental note to educate the patient regarding low back pain and disc degeneration as this is a common misconception. Specifically, I provide education in the form on an analogy. A common analogy I use for disc degeneration is the 'wrinkles on the inside' concept, which discusses that we age internally just as we age externally! Despite his anatomical answer to question 9, he acknowledges that his osteoarthritis is 'age appropriate' in question 10. I will still discuss disc degeneration, but hopefully it will be a welcomed conversation. Question 11: As a result, I am having difficulty with? This particular client is not having too much difficulty with specific activities, but rather wondering the difference between 'good' and 'bad' movements. His response is positive because likely he has a low level of overall irritability. Other patient's respond with detailed language that insinuates a fear of movement. Based on his response, I already anticipate a quick return to full activity. For question 11, my focus will be providing education on posture and movement. Newer studies on posture and pain, have demonstrated there are no 'good vs. bad movements.' My education would go as follows: "As humans beings we are designed to move. You have probably heard the quote 'movement is medicine.' It is absolutely true! All movements are great as long as our brain and body are adequately prepared for the movement! To live healthy lives, we must have the capability to explore the bad posture positions equally as well as we can perform the good postures." Question 12: This answer reaffirms his low level of irritability! I am good to proceed to Question 13. Question 13: When did your symptoms begin? This patient provides two answers to his onset of symptoms, either recently or decades ago. From his response, I can gather that he is experiencing a recent onset of a chronic injury. As someone who treats the neuromusculoskeletal system, I am interested in both answers. His older injuries and how he managed them will directly play into the management of this recent onset. Most importantly, I want to know how his January 1969 injury plays into his current symptoms. There must be a strong connection to his original injury if he reports the month the event began roughly 50 years ago! This answer is worth exploring in greater detail during the subjective interview. Closing ThoughtsThe words we use and how we use them have an immeasurable impact on a patient. If ‘thought viruses’ have the potential to worsen a patient’s prognosis, the opposite must also be true. Learning to evaluate a patient's language even before they arrive at your clinic can prepare you for the upcoming evaluation. As health and wellness providers, the ability to understand someone’s needs, and tailor one’s language toward these needs, can significantly influence the outcome of their situation . Author: Jim Heafner PT, DPT, OCS More from The Student Physical TherapistComing out of physical therapy school, one of the many things I was uncertain about was when it was okay to manipulate a joint in the geriatric population. Obviously, some of the usual standard contraindications are included: fracture, instability, etc. However, bone density deficits can be difficult to identify in evaluations as patients don't always have recent (or sometimes any) knowledge of their bone health. To assess bone density, a patient has a DEXA scan performed. The standard deviation then plays a role in assessing how severe any density issues may be. If the score is less than 1 standard deviation from the norm, it is still within the normal range. If the score is within 1-2.5 standard deviations of the norm, the area is identified as osteopenic. If the score is greater than 2.5 standard deviations from the norm, the area is osteoporotic. Should a patient present with either osteopenia or osteoporosis, it is not recommended to manipulate the joint. It would be wonderful if it was as simple as that. However, not every patient knows if they have poor bone density. They may not have gotten a recent DEXA scan. Because of this, we should consider other factors that may contribute to poor bone health and lead to density issues: long-term corticosteroid use, cancer, older age, female, poor nutrition, and more. Should a patient have any or several of these factors, they may very likely have bone density issues as well. This is further evidence that a thorough evaluation (especially subjective history) is essential in patient management. Their history may indicate the safety with joint manipulation. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS Looking for advanced sports and orthopedic content? Take a look at our BRAND NEW Insider Access pages! New video and lecture content added monthly.

The overhead athlete is a unique type of athlete to treat in physical therapy. When I think about the different types of overhead athletes I include the baseball thrower, tennis player, and even the quarterback. Each of the mechanics of these athletes is different and present unique challenges (load, speed, intensity, biomechanics, etc). However, while each of these athletes are different, some of the exercises can be tailored to each sport. Recently, I was working with a competitive high school tennis player. He presented with a very stiff shoulder and diffuse pain. When I say stiff shoulder, I mean he had very limited shoulder flexion, abduction, and inability to get into a 90/90 position without pain. His postural presentation was a significantly lax R shoulder (hanging down), flat t-spine, and scapular winging. After some time working on pec minor, lat, and subscap tone he was able to start to recruit some of his scapular stabilizers (primarily serratus & low trap) much better. However, his rehabilitation took off once he had good shoulder flexion ROM and we were able to start to work on overhead stability. So what overhead stability exercises did I use?

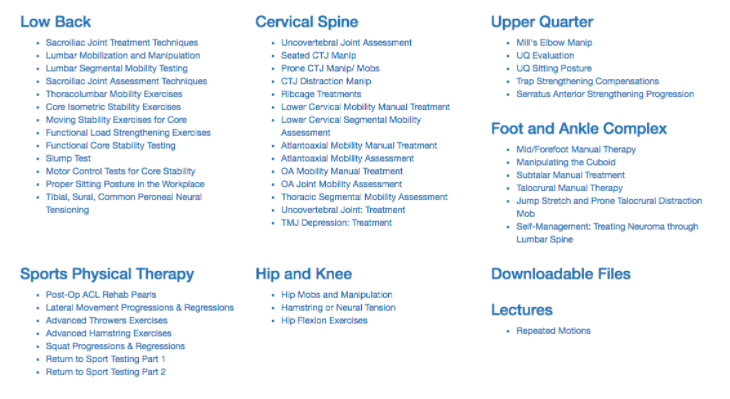

What else do you use for overhead stability? Comment below and let me know - Dr. Brian Schwabe, PT, DPT, SCS, COMT, CSCS Looking for advanced sports and orthopedic content? Take a look at our BRAND NEW Insider Access pages! New video and lecture content added monthly.

|

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed