- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

Within the next couple weeks, many will be taking the NPTE and starting off their careers as PT's. Hopefully you have been studying hard the last few weeks or months and are stress-free and ready for the big day! In reality, many often feel anxiety and panic set in as the exam gets closer. You may feel like you need to keep cramming up to the exam, have given up hope or have no idea what to do at all! Take a deep breath, and try a few of these steps: 1: The day before the exam plan to do something relaxing. Whether it's seeing a movie, going for a hike, hanging with friends, or any other stress-relieving activity, you should take your mind off the exam in some way. If you absolutely feel the need to study, take just a little time that day to review a small study guide you may have created. This isn't the time to learn something new. It's time to reinforce areas you already know. I watched a movie and ate some ice cream the night of the exam! 2: I recommend some light exercise the morning of the exam. If you like to go for a walk, run, bike ride, lift weights, or whatever, do something to get the blood flow going and open up your mind. Getting up and moving early will help prevent you from feeling tired during the long test. 3: Eat something healthy in the morning. While you do get a break during the exam, you likely will still be hungry. Your mind works better with energy, don't let skipping a meal get in your way of doing well on the NPTE! 4: Finally, be confident! You have graduated PT school already, which was the hard part. You've done the studying over the last few weeks or months. You know the material. You will rock the exam! Once you are done with the exam, celebrate! I know you don't know the result yet, but you completed the NPTE. You won't know the results for at least a week, so you might as well do something to take your mind off the exam. Go on a vacation, hang out at the pool, spend time with friends. There is no point in worrying about the score at this point, so just enjoy your time! -Dr. Chris Fox, DPT, OCS

6 Comments

Hip extension mobility and anterior chain extensibility are assessments that should often be considered in patients with ankle/foot pain. Often, we see that ankle DF and hip ext ROM are limited simultaneously in patients and one can impact the other. When we are assessing gait, a patient will have difficulty with terminal stance phase due to either of these issues. The ankle and hip must each achieve 10-20 deg of DF and ext accordingly. A limitation in either of these may lead to compensation: early heel rise, excessive lumbar extension, shorter stride length, etc. In the case of Lumbar Extension or Extension-Rotation Movement Impairment Syndromes (MIS), typically we see loss of hip extension mobility leading to excessive lumbar extension motion in standing, walking, or supine positioning. Anything that requires the hip to move into extension will instead move in the lumbar spine, due to flexibility deficits. Over time, this may lead to a painful state. Increasing hip extension mobility may help the local motion, but if the functional pattern (gait) and associated impairments aren’t address as well, the patient may continue to have difficulty with an activity like walking. A patient may have gained enough hip extension mobility to achieve normal terminal stance positioning; however, the restricted ankle DF motion must be also be improved to see the change in gait. So how do we make sure that we don’t miss these impairments in our exam? The answer is simple: make sure you do a thorough exam that is efficient and a standardized procedure. My exam sequence for strength and mobility looks identical in >95% of my lower quarter patients (minus adding/subtracting a few special tests each time). If you make it a habit, you will be much less likely to miss it. So make sure in your foot/ankle patients, you are assessing hip ext mobility as well looking at ankle DF mobility for your low back/hip patients. Dr. Chris Fox, DPT, OCS

There is belief among the manual therapy-trained that thoracic manipulation may be beneficial for almost any condition due to its effect on the nervous system. With the nervous system being connected from head to toe physically and the input to the central system, a manipulation to the thoracic spine may potentially impact the patient peripherally and/or centrally. Take any individual and measure their SLR ROM. Perform a thoracic manipulation and then remeasure the SLR mobility. Often, you will see a change that appears like we are facilitating. There have been many studies showing that thoracic manipulation does not show any difference between sham manipulation in improving shoulder pain and muscle activation (Bizzarri et al, 2018 & Grimes et al, 2019). Studies like these contribute to the heavy anti-manual therapy rhetoric by some practitioners and academians. However, can/should we ignore the fact that we can get some sore of change in something like SLR mobility with the technique? Maybe we should consider that the manual contact or verbiage we use in the sham manipulation to get the change as there is no difference compared to thoracic manipulation. While some are completely against incorporating manual therapy in treatment and others are heavy manual therapy-biased, I try to fall somewhere in the middle. It's clear that manipulation doesn't have the biomechanical effect we once thought it had. However, it is not clear that manual therapy, placebo or not, doesn't have some sort of impact on the nervous system. The contact of the hand is still an input to the system. It would appear that further research is needed to determine what exactly that impact is. -Dr. Fox, PT, DPT, OCS References: Bizzarri P1, Buzzatti L2, Cattrysse E3, Scafoglieri A4. Thoracic manual therapy is not more effective than placebo thoracic manual therapy in patients with shoulder dysfunctions: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2018 Feb;33:1-10. Grimes JK1,2, Puentedura E2,3, Cheng MS2, Seitz AL4. The Comparative Effects of Upper Thoracic Spine Thrust Manipulation Techniques in Individuals With Subacromial Pain Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2019 Mar 12:1-28.

Last week, I woke up one day with severe R anterolateral shoulder pain and inability to raise my arm above shoulder height. In the days preceding, I had completed approximately 8 hours of painting and a heavy shoulder workout, all without pain. Initially, because of the severity of the pain and inability to raise my arm above my shoulder, I became extremely fearful of my inability to fully treat my patients, sleep, or do much of anything with my right arm. Self Exam: Right Shoulder AROM: flexion 80 deg, abd 45 deg, ext 30 deg, IR 45 deg, ER 20 deg R shoulder isometric strength: strong and painless in all directions at 0 deg abd Cervical AROM: full and pain-free in all directions (+) Obrien's Test My shoulder was strong and essentially pain-free when at my side. Treatment: My primary treatment was to limit motion of my RUE to range with minimal discomfort, 5-directional resisted isometrics of the right shoulder at my side, and Quad Rock Back to perform CKC shoulder flexion AAROM. Additionally, I performed repeated shoulder extension with horiz. abduction in CKC between each patient treatment session. I took some anti-inflammatories each day to help encourage movement as well. Over the span of the next few days, my shoulder gradually improved and I got back into some weight-lifting with my focus being legs, posterior shoulder/scapular and some running. Some of the initial testing was positive for labral tear. That plus my significant loss of ROM made my mind start running off into hypotheticals: will I need surgery, how long will I need off work, how can I support my family? As we are all aware from pain science research, these thoughts only serve to raise my pain-level. I had to continually remind myself not to jump to conclusions and to remember people have injuries like this all the time and recover. I'm not sure if the pain was due to RTC syndrome or labral tear or something else, but it shouldn't matter too much due to the lack of correlation between pain and imaging findings. While I am grateful to be nearly fully recovered, the experience was enlightening to me about how various factors can impact a patient's fear and pain experience. It reinforced the importance of addressing all concerns of the patient for an injury, especially the biopsychosocial factors. -Dr. Chris Fox, DPT, OCS

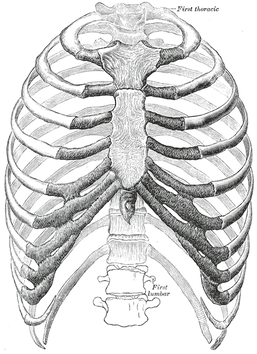

Last weekend, a colleague of mine called me because her husband had severe "rib pain," so I went to take a look at it. Apparently about a week ago he developed pain in his R chest and back but significantly worsened earlier that day when playing basketball with his daughters. The pain was located pin point at sternal end of 3rd rib and some mild pain at vertebral end as well. The pain was constant but had a significant increase with transfers, rolling, and laying on his side. Examination: Cervical AROM had a slight increase in pain with rotation but no change with flexion and extension. Mobility was moderately limited with all motions. Thoracic rotation was mildly painful and BUE myotomal strength was 5/5 throughout. Pinpoint tenderness was noted over the R anterior 3rd rib near the sternal attachment. It "appeared" anterior and hypomobile relative to the surrounding ribs, but testing like this has pretty poor diagnostic capability. Treatment: I did a thoracic, rib and CT junction manipulation. The patient was instructed to do some general thoracic/rib mobility exercises, use various methods to address the pain (OTC pharmaceuticals, heat/ice, gradual increase/resumption in activity). I educated the patient on the fact that injuries like these can be painful initially, but they do get better typically quickly. It's important to stay away from pathoanatomical diagnoses as it can make the patient think they are fragile. While I referred to the case study as "rib dysfunction," I do not and cannot know if the rib was truly involved, even with how abbreviated the examination was. My goal was to lower the threat level by introducing motion to the involved areas. Once the restricted areas were identified, lowering the threat level was done through education, manual therapy and exercise. The key is to guide the patient through the painful experience, by being a resource and assisting self-management for addressing the injury. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

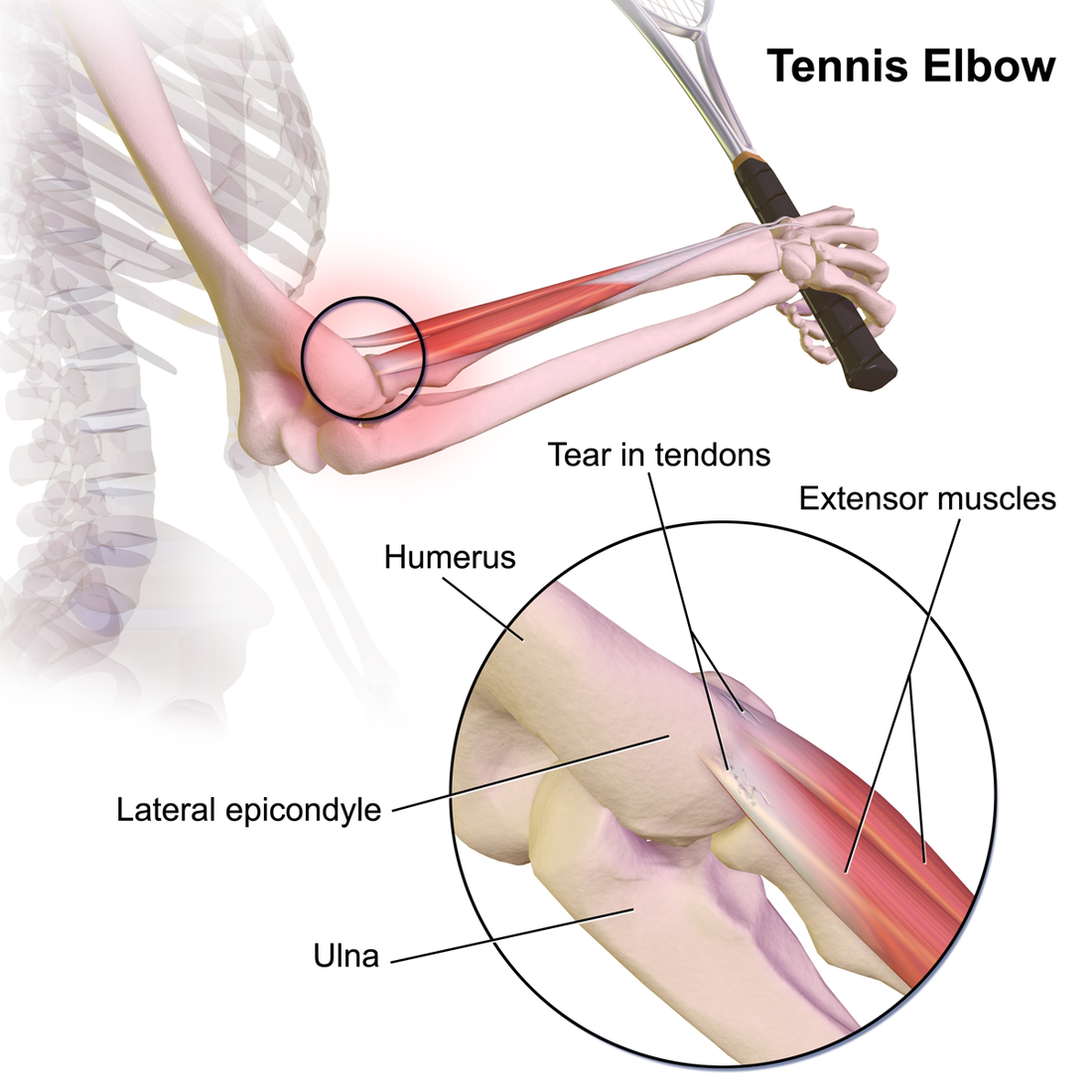

One of the topics we regularly return to is differential diagnosis. While ruling out non-musculoskeletal conditions is an aspect of this, we also want to be aware of diagnoses that present somewhat similarly but may be treated differently. Now, we recognize that pathoanatomical findings and management are not what we once thought they were; however, there are some differences on what the research shows for treating tendinopathy versus nerve entrapment. I won't focus much on treatment in this article, but instead on differentiating between the two diagnoses of lateral epicondylopathy and radial tunnel syndrome. Presentation: While both diagnoses often present with "elbow pain," the location may help indicate which diagnosis is more likely. Lateral epicondylopathy (LE) typically has some pinpoint pain over the lateral epicondyle but may radiate down into the forearm as well. Radial Tunnel Syndrome (RTS) typically has pain in the proximal forearm around the supinator (lateral to the brachioradialis) but distal to the lateral epicondyle. There may be some tenderness around the lateral epicondyle but it's not quite as significant as in lateral epicondylopathy. I recognize it sounds like these diagnoses are almost identical in pain location, but the proportion of pain location relative to the other is the leading factor. In fact, often ,in cases of lateral epicondylopathy, there is some radial nerve adverse neural tissue tension (ANTT) associated with it as well. Both LE and RTS symptoms are typically aggravated with increased use of the elbow/wrist muscles and alleviated with less use. RTS may be worsened with abnormal neck positioning/motion due to the altered neurodynamics. Additionally, the impact of compression may help with diagnosis. With appropriate positioning and force, compression of the forearm will "feel good" for LE and irritate those with RTS. Examination: As you likely may have noticed previously, I strongly encourage a standard exam, where most of the motions are tested for all upper quarter pain. This means I assess cervical, shoulder, thoracic, elbow mobility for all upper quarter patients. In diagnoses like LE and RTS, wrist/hand and forearm motion is assessed as well. With strength assessment, I will always test the shoulders, elbows, wrists, and scapula for upper quarter patients. How the patient responds to some of the tests may vary in the diagnoses. With resisted wrist extension, LE will likely be more painful than RTS although it may be painful in both. With resisted supination, RTS may be more painful than LE, but, again, it may be painful in both. Even though, the strength and mobility testing here may not appear super useful for differentiation, it is still beneficial for identifying impairments. Special Tests: Lateral Epicondylopathy: -Cozen's Test -Mill's Test -Maudsley's Test: resisted middle finger extension with palpation of lateral epicondyle Radial Tunnel Syndrome: -Radial Nerve ULNT (will reproduce patient's pain in RTS, but may still have some tension present in those with LE and associated radial nerve ANTT) A test that I learned but an unfamiliar with an official name involves trying to affect the pain via compression. The patient will make a strong fist and note the pain level (a dynamometer may be used for this as well to measure grip strength). The PT will then use his/her hands to compress the proximal forearm and the patient will make a fist again. Any changes in pain and strength will be noted. For a patient with RTS, the pain may increase and grip may be weaker. For those with LE, the counterforce will likely feel better and grip strength will improve. I'm unaware of the diagnostic accuracy of this test but has seemed useful and relates to the concept of counterforce bracing. Summary: It should be apparent that RTS and LE are not easy to differentiate as the pain presentations can be somewhat diffuse and testing may present similarly, especially in cases of LE with associated radial nerve ANTT. With that being said, I recommend starting with treating the associated impairments. Improve joint/muscle/nerve mobility where it is restricted and strengthen areas that appear weaker. Where being able to diagnose the primarily affected area become more important is management of the condition. Treatment to the cervical spine is especially important for cases of RTS as is isometrics/eccentrics for cases of LE. There is some research to show these benefits; however, patients with both diagnoses would likely benefit from these specific treatment anyways! -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

A few months ago, a PT student reached out to me asking about sports residency programs. He wanted to know what my experience in one was like, how it helped my career, and what he should do to try to put himself in a position to get one. This was not an uncommon question as I get at least 15-20 emails like this yearly. However, my answer to these type of questions has changed over the last few years. What was my experience like in a sports residency? If you would have asked me this question during my residency I would have told you amazing and also very stressful. Now, looking back, I would still say that it was an amazing experience but I would also say I see there are "different" paths that can be taken depending on career goals. What I mean by that is you can certainly create your own "residency" experience. For example, if you are looking to work in a collegiate setting you may want to do a more structured residency experience with a university. However, if you want to work in a clinic setting that deals with primarily athletes and does event coverage then chances are you can find a clinic like that while using the money you will make to create the type of education you want. How has a sports residency helped my career? Completing a sports residency has done a few things for my career that I don't think I would have had without it. The first being the skillset to feel comfortable taking an athlete from the start of rehabilitation to the end of rehabilitation. I think that the orthopedic skillset that is required at the start of rehab is crucial but the understanding of the sport biomechanics, demands, athlete mindset, and proper loading progression to get back to sport is something extra I learned consistently working with my mentors. The second way I think the residency helped my career is put me in a network of people I could learn from. It wasn't just my immediate mentors but more the ones that I was able to reach out too being a sports resident that helped me get my foot in the door with them. These people that I looked up to were more than willing to talk with me and while they probably have helped numerous other clinicians, I do think it helped that I was a clinician that chose to do a residency to advance my career. Lastly, completing the sports residency helped me gain the confidence to treat any athlete effectively. This has helped me advance my career by landing consulting gigs with gymnastic and AAU teams which has been very rewarding. What should you do to get into a sports residency? I wrote a great article right after my sports residency interviews about this here but the main thing is do as much in the sports world as you possibly can. That can include going to the sports section conference, volunteering at marathons, taking sports PT courses, taking additional internships in sports, and more. The more a residency sees your passion for sports physical therapy the better. Lastly, make sure you reach out more than once to these directors or go visit them in person. This is a great way to stand out. Overall, doing a sports residency is a choice. You can certainly build out your own "residency" experience by choosing your own education, using the extra money you earn as staff PT to travel to meet more sports clinicians, and volunteer in your local community at events. However, structured residency experiences also have there advantages and can certainly make it easier to get consistent sports experience and mentoring. Dr. Brian Schwabe, PT, DPT, SCS, COMT, CSCS Young clinicians often ask me, "how were you able to start your own cash based practice within 3 years of graduating?" While hard work and passion are at the center of this answer, properly positioning myself around the best mentors and educators early in my career was equally important. These mentors largely came from my Orthopedic residency program, the Harris Health System. My residency program taught me pain science education, manual therapy treatments, improved clinical reasoning, differential diagnosis, and improved patient education/ communication. If you combine all of these components into a patient interaction, you hopefully get an efficient and effective Orthopedic clinician.

From opening a cash practice to finding fulfillment, in this post I discuss the need to pursue specialization!

Specializing is Worth It: Your Outcomes Will ImproveSince the majority of physical therapists are caring and compassionate individuals, it is safe to assume that most people who become Doctors of Physical Therapy have a primarily goal of helping others. Furthering this assumption, I would guess that getting patients healthier as fast as possible is even better! For me personally, I know that this is my primarily goal. Going through a residency program and preparing for the Orthopedic Clinical Specialty examination taught me how to quickly improve my patient's pain and function. Additionally, I learned how to become a direct access practitioner. As the entry-point diagnostician, it has always been important for me to know when to treat, but more important to know when NOT to treat. As I studied the clinical practice guidelines and APTA monographs, I learned how to incorporate this evidence into my patient interactions. Instead of passively guessing a patient's prognosis, I learned to actively create a plan of care with a predictable prognosis. As my knowledge improved, my outcomes continued to get better! Specializing is Worth It: You Will Be More Fulfilled

While I am always developing my practice, my training as an Orthopedic Specialist allows me to view each patient from a different viewpoint. I credit my OCS preparation and residency training for providing me with a deeper understanding of pain science, tissue pathology, and biomechanics. This deeper understanding allows me to provide specific education to each patient based on their individual needs.

As more residencies are being credentialed each year, the awareness and availability of residencies have also increased. With this development, more PT students show interest in pursuing residency, but the question remains, "when is the right time to pursue residency?" There is no correct answer, as each person and situation is different. Now a residency is not right for everyone. Even with the twelve residency specialties available, the educational pursuit may not be possible or desired. There are some that like to be "generalists" and treat a wide variety of conditions in different settings. While it is not currently a specialty, it may eventually become one. For others, residency may not be financially possible. It can cost income/tuition temporarily and may not lead to an increase in pay upon graduation. There are over 250 credentialed residencies currently and all have different pay and tuition requirements. Some offer very reasonable salary/tuition options compared to "standard local wages," while others are relatively expensive and make it difficult to live off in high cost-of-living regions. With residency pay cuts, it may be easier to manage immediately after graduating PT school (one typically has less expenses immediately after school i.e. may not have a mortgage or kids) or if one has a spouse or family member to help support housing or other living expenses. As for education and clinical development, timing is different for each individual. Some people, myself included, find that when graduating from PT school, it's easiest to roll right into residency since the mind is still in a "learning state." I knew that I wanted to learn more and specialize in orthopaedics immediately. I felt like I didn't know enough about my area of practice upon graduation. That is not the case for all. Many people do not know right away in what they want to specialize. For those, it may be best to practice (or perform clinicals in various areas) for a few years to solidify interest in a specialty. There isn't necessarily a rush to specialize or complete a residency, so if uncertainty exists, take your time. All that being said, I still highly recommend residency pursuit. While one learns plenty of clinical knowledge and hands on skills, the two best things that come from residency are clinical reasoning development and how to critically appraise research (and apply it). Clinical knowledge changes with time, as does research. The ability to stay up to date on research an identify study limitations/applications is essential for "evidence based practice." Clinical reasoning skills helps with problem solving, self-reflection, and clinical development. A residency teaches all these things and holds one accountable to certain standards. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

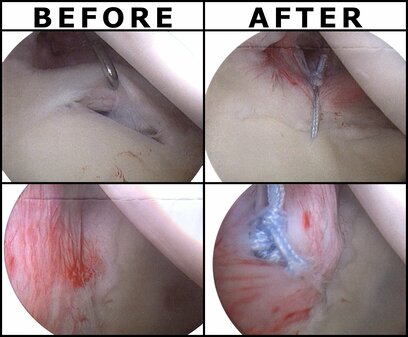

Over the last year I have seen more and more athletic pubalgia in the clinic. Some of this is because of the population of athletes I have seen and some of this is because of the sports medicine doctors I work with. Athletic pubalgia (also known as sports hernia) is also defined as non-specific referral of groin pain. This injury can be complex to treat or very straightforward depending on the severity. Understanding how to determine if this is a AP and how to effectively treat it to return back to sport is crucial for the sports clinician. Typical presentation of athletic pubalgia includes:

Other pathologies to consider:

One of the key points to make with AP is that despite the term “sports hernia”, AP is not a hernia. Furthermore, this injury can be chronic in nature. With all that in mind, there are many conservative treatment options. From a conservative standpoint, treating AP has some non-negotiables. The first phase as many pathologies require, it to control the pain and symptoms. The length of this phase will be determined by severity, sport demands, and previous injury history. However, there are many other things you can do during this phase away from the site of injury to keep the athlete in shape. It is crucial to maintain cardiovascular endurance and strength elsewhere to give the athlete the best chance of returning without another injury later. Following the first phase you can you can start to work on more advanced core strengthening with “neutral spine”. I say neutral for the purpose of discussion and because most research articles advocate neutral spine but understand that everyone’s “neutral” is different. Another important point to consider during this phase is the influence of the lumbar spine. As with almost all hip injuries, we MUST consider the influence of the lumbar spine. Make sure full ROM is achieved and good control over the stability of the lumbar spine as it will influence the pelvis. More often than not, we can indirectly influence AP with lumbar spine treatment. Lastly, slowly adding adductor specific exercises from isometric in nature to more dynamic is important to add proper strength back to this athlete. I like the Copenhagen plank for a good isometric exercise vs squeezing a ball because it is hard to quantify the “squeeze”. There are many different forms of Copenhagen exercises and I would urge you to watch youtube videos, try them yourself, and determine if and when each variation can assist (or not) with your athlete’s rehabilitation. Finally, as with all injuries, proper return to sport criteria MUST be measured. While hip return to sport tests are few, there is good research on some tests and more importantly, a proper “battery” of tests must be put together. There is no one approach for return to sport and for those of you who have gone through our “Sports Management for the Orthopedic Clinician” course, you already learned how to put your own battery of tests together for various hip pathologies and how to properly construct return to sport testing. Dr. Brian Schwabe, PT, DPT, SCS, COMT, CSCS Board Certified Sports Physical Therapist |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed