- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

|

Dry needling appears to be the new "technique" that orthopaedic therapists are trying to learn. It's different, there is a demand, and there are reports of success. With this, unfortunately, comes expensive classes. Is the potential benefit worth the expense? Now, with all these factors comes a certain level of controversy. In fact, there are some out there that almost appear to have alerts set up for whenever a dry needling post comes up, so that they can lecture about its "ineffectiveness" and lack of evidence. Understandably, one of the most important critiques of dry needling as an intervention is the lack of high quality evidence to support it. While this is true, there are several reasons why we shouldn't suddenly abandon the potentially useful intervention altogether. For one, part of the lack of research is secondary to inconsistencies in technique and the studies. I'm aware of 3 programs locally and know that all three have different methods of dry needling. Secondly, research is only one of the three pillars of evidence based practice. The other two include patient preference and clinical experience. If a patient reports prior success with dry needling, it may prove beneficial to include in your plan of care. The clinical experience can be seen with changes being made in a specific asterisk sign from the one intervention of dry needling. While I will not argue the specific mechanism, it likely works through acting as a novel stimulus to the nervous system to alter threat levels. To build off that I want to give you a quote about how we should interpret research and implement the findings into practice: “However, the authors caution against interpreting EBP to mean that good practice should consist of only application of those tests and measures or interventions currently backed by good-quality research evidence...Likewise, when tests/measures and/or various interventions are proven to be faulty or ineffective through good quality research, it is reasonable to argue that they should not be used in practice. However, if there is no relevant evidence available, or if the evidence that is available is of questionable quality, clinicians must rely on other theoretical knowledge and practice experience, integrated within a sound clinical reasoning process, to determine appropriateness of tests/measures and interventions that have not yet been adequately researched (Christensen et al, 2011).” With the push for physical therapy to be more research-driven, many have put the potential highest quality of evidence on a pedestal. Many have forgotten that much of what we do as physical therapists has not been studied or the studies lack true isolation of variables. Because of these limitations, we must remember to not be so close-minded as to eliminate potentially useful interventions. As many of you know, pain is more of a perception and we must impact the nervous system and the patient's beliefs to truly alter their experience. There are some patients who will have excellent responses to dry needling. Let's not limit those patients' potential improvement simply because research is lacking. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS Reference: Christensen N, Jones MA, Edwards I. Clinical Reasoning and Evidenced-based Practice. Current Concepts of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy, 3rd Ed. La Crosse, WI. 2011.

2 Comments

Patient's often present to the clinic with pathoanatomical diagnosis'. For example, they may have a referring diagnosis of a rotator cuff tear, hip bursitis, or sciatic nerve pain. While this information can often guide us to the region involved, it rarely sheds light on the underlying cause of the problem. As a profession, it should be our goal to be experts in treating the movement dysfunction. Do you find yourself treating local anatomy or searching for underlying movement problem?

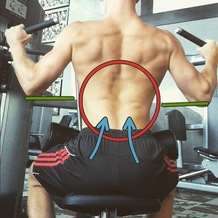

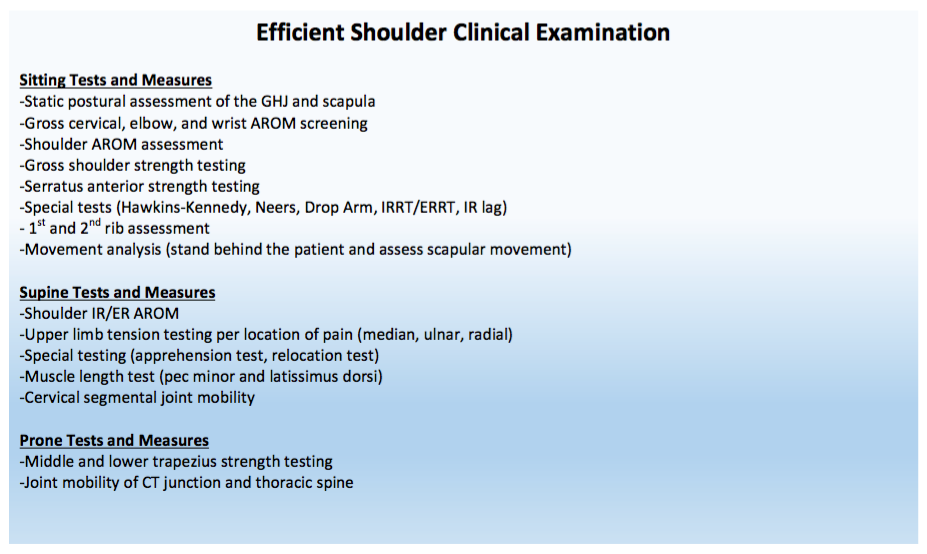

In my recently published clinical booklet, 'The Guide to Efficient Physical Therapy Examination,' I stress the importance of having a movement based examination process. For example, during a shoulder evaluation, the majority of special tests taught in physical therapy school assess specific tissue dysfunction (biceps tendinopathy, labral tear, etc...) Additionally, many of these tests have poor statistics. Remember, we need to assess movement dysfunction - not anatomical tissue dysfunction! Below I have included my step-by-step shoulder examination. In my standard exam, you will not see glenohumeral joint mobility testing or strength testing of the rhomboids. These tests are typically not indicated. The glenohumeral joint is built for mobility, unless the individual has clear mobility deficits (i.e. adhesive capsulitis), joint mobility is usually not an issue. Additionally, many people rest in scapular downward rotation and demonstrate strong and dominant rhomboids muscles. While your personal examination may include or exclude certain steps, always remember that we are movement specialists and your testing should be guided by movement impairments.

-Jim Heafner PT, DPT, OCS

Recently, I have been reading the McKenzie texts in order to gain a better understanding of the foundation material. I had previously gotten my education on utilizing repeated motions from The Manual Therapist and then developed my practice through clinical implementation since then. Typically, when people think of McKenzie, they simply think of everybody doing lumbar extensions. After going through the lumbar spine text books, it is refreshing to see the standardized approach in the McKenzie system. However, I would argue the school of thought doesn't address the lumbar spine enough. The McKenzie system is very anatomy driven. The theory is built off of addressing disc herniations, radiculopathy, and more. While each patient is expected to be taken through a standardized assessment of repeated motions in various directions, should no significant signs of lumbar involvement be present, the lumbar spine may not be addressed. For example, one of my former students and I had a patient with all signs of an acute meniscus tear, confirmed with imaging and testing. He did not respond to any local repeated motions but had complete elimination of pain with spinal repeated motions. With a personal example, I had signs of either a neuroma or metatarsalgia that responded perfectly to repeated motions in the lumbar spine. An experienced McKenzie therapist may have addressed the lumbar spine in examples like these, but it doesn't fit the typical diagnostic criteria. With what we know about "double crush syndrome" and pain science, we must address any potential perceived threat in the body. Typically, one of the biggest drivers of neural sensitivity comes from restricted spinal mobility. In pretty much every injury, the spine should be assessed for mobility deficits and addressed. Otherwise, long-standing "calf strains," meniscus tears, trochanteric bursitis and more may go without improvement. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

Recently, a new online resource was launched to help stay up to date on new things in the physical therapy world. If you're like me, you likely find it difficulty to stay on top of all the new research and blog posts out there. It seems like just a few years ago that only a few blogs were out there and now almost every other PT has one. That's a lot of information to keep track of! Thanks to Innovate Physical Therapy, there is now a website where links to many of the top new blogs and studies are posted. With it being updated regularly, you can keep track of much of the new content. Check it out! -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

MTSS or "shin splints" (as called by most patients) is a tricky injury that often goes misdiagnosed for some time. It is an injury that can limit many activities. I recently wrote an article on some of the most common questions and treatment methods associated with MTSS. While this was geared towards patients and consumers, it is something that I hope everyone can take something from. Check it out here: http://blog.paleohacks.com/shin-splints/ - Brian  For the past few weeks, I have been reading through the McKenzie text books in order to establish a stronger foundation on source material for repeated motions. Those of you familiar with repeated motions know that posture plays an essential role in treatment. In the lumbar spine books, it is recommended that we have our patients sit in a chair without a backrest, so that we can see their "natural" posture. I disagree with this for several reasons. One, I believe it is important that the patient be as comfortable as possible during the evaluation. The patient will immediately begin to have increased trust in you, the patient will be able to focus on a more accurate subjective examination, and it helps to avoid flare-ups during the evaluation. Second, most patients will regularly assume a more comfortable position (or what they view as being comfortable). It is best, in my opinion, to see how the patient regularly sits. For example, some patients with low back pain will exhibit a slouched posture with excessive lumbar flexion, while some others will sit on the edge of their chair using their hip flexors for stability in the upright position (remember the iliopsoas acts as a spinal compressor!). Regardless, simply addressing these issues may take care of the patient's pain while sitting. There is a lot of debate out there on should we or should we not assess posture. Those that argue against it, say "look at all the people sitting poorly and have no pain." I will respond with the fact that pain with these prolonged positions can be corrected if the posture is corrected. Now, I wouldn't attribute the problem and fixes to mechanical factors in the tissues. I typically explain it as a hypersensitivity of the nervous system towards one prolonged position and that we need to balance it out and work to keep things more even across the equilibrium. Overall, I recommend trying to get a picture of how the patient acts in their natural habitat and addressing any contributing factors. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

|

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed