- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

RehabilitationAfter the diagnosis of an ankle fracture has been made, the region is typically immobilized with limited weight-bearing. The severity and location of the fracture contributes to the decision on what level of immobilization is required: open reduction internal fixation, CAM boot, aircast, etc... This timeframe for immobilization typically occurs for 4-8 weeks (factors like osteoporosis and peripheral vascular disease may impact the timeframe). Once radiographic evidence of sufficient healing occurs, the patient often begins skilled physical therapy. Initially, the primary focus will be on reducing swelling and improving joint mobility. This is often done with ROM and stretching exercises, joint mobilization, soft tissue treatment, and modalities. Open-kinetic chain strengthening exercises are typically started once the patient's fear of movement and activity tolerance improved. During this initial acute phase, gait training may be necessary to train the client on how to use crutches, how to maintain appropriate weight-bearing status, etc. As the patient gains mobility and weight-bearing is progressed (based on bone healing), weight-bearing exercises will be progressed. The patient may initially need to perform AAROM exercises in closed-kinetic chain in order to address any apprehension and improve load tolerance, while restoring mobility. Full ankle motion is not required nor expected before weight-bearing is initiated. Once the patient presents with sufficient tolerance, closed-kinetic chain load is progressed further with shuttle squats and calf raises, to full body versions as well. Exercise progression becomes more typical at this point as various methods of loading (lunges, squats, step-ups/downs, etc.). What likely needs to be addressed is stability training in some form to improve reaction and balance when stability is challenged. This can include standing on unstable surfaces, incorporating mental and upper extremity tasks, agility/plyometric training, etc. This progression has no set time table. We have to respect the severity of the fracture, co-morbidities, prior level of function, planned activities to return to and more. Always consider the physician and/or surgeon's prescribed progression, but move your patient through the various phases based on how that specific individual is doing. A patient with a fibular fracture that also suffered a common peroneal nerve injury will likely not progress as quickly as the same fracture without neurovascular insult. There is no set timeframe for recovery from injury, so prepare to be flexible. You may need to incorporate other treatment methods to help move your patient through each step (spinal manipulation, nerve mobilization, therapeutic neuroscience education, among others). Regardless of the contributing factors, the therapists' objective is to guide the patient back to their prior level of function safely. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS Want to learn more advanced information to develop your clinical skills and knowledge? Check out the Insider Access Page!

1 Comment

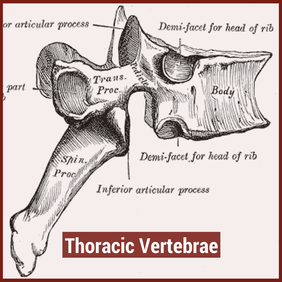

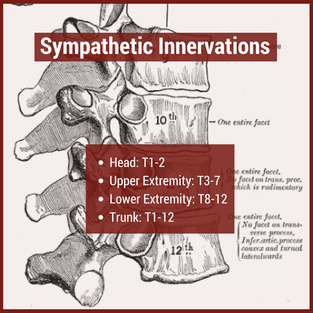

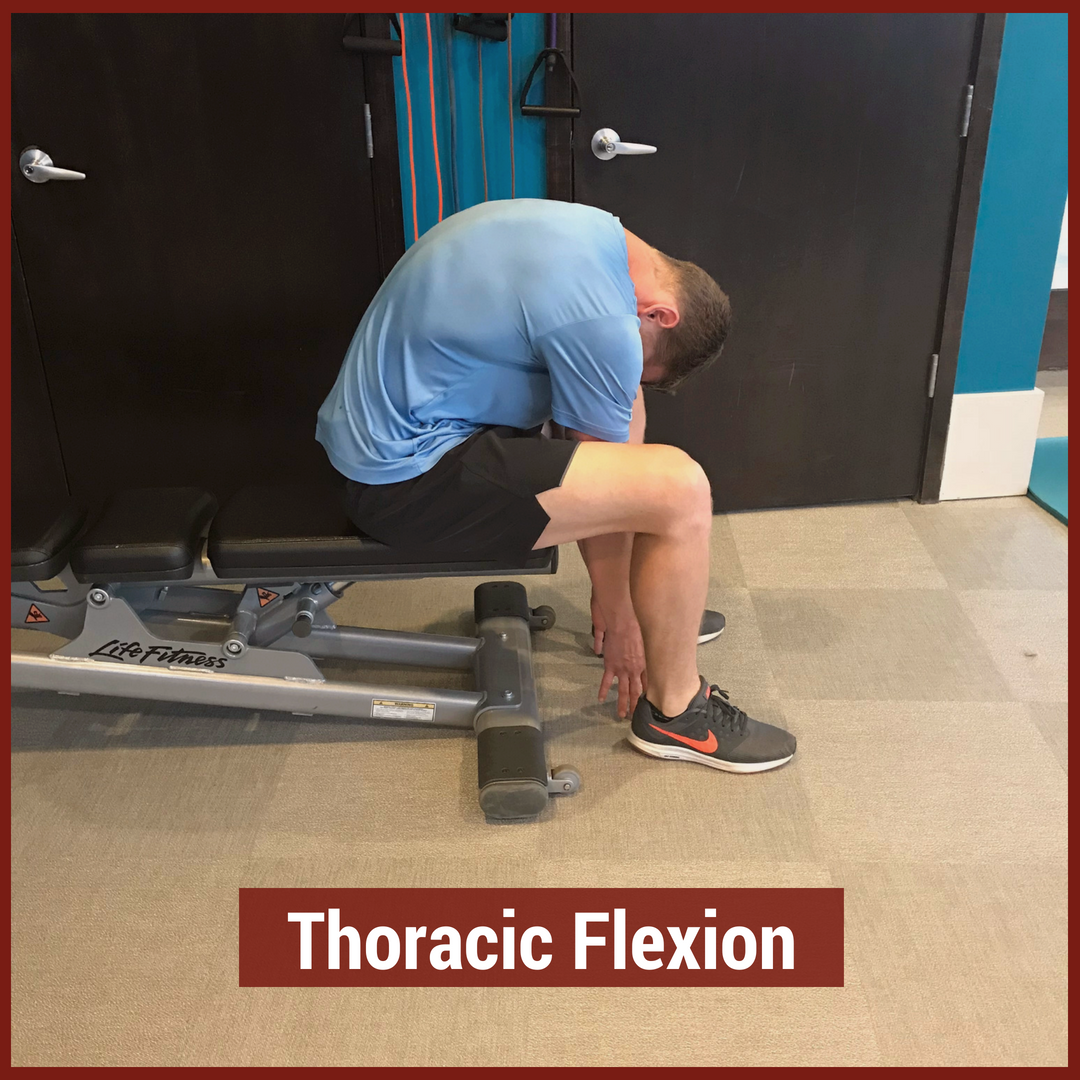

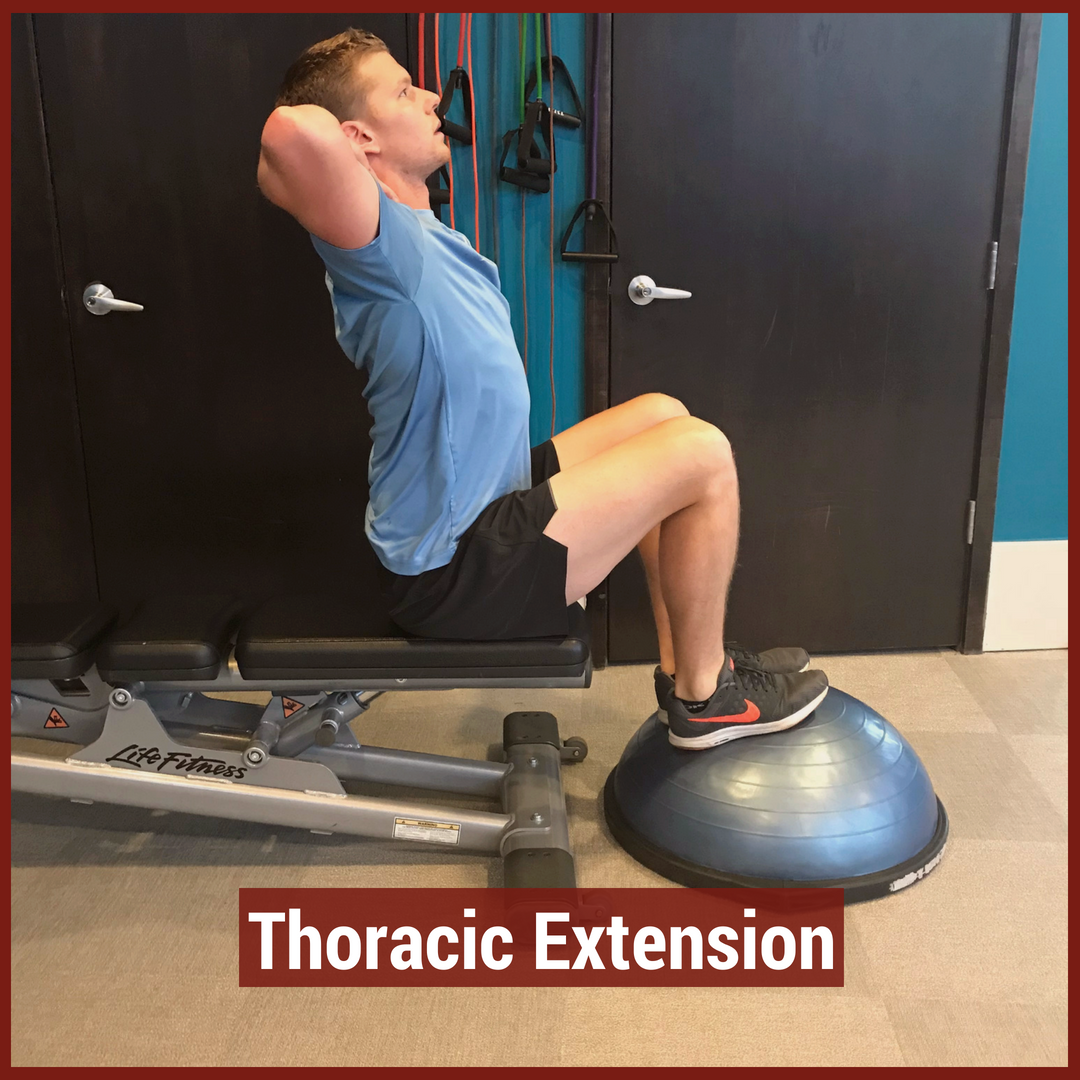

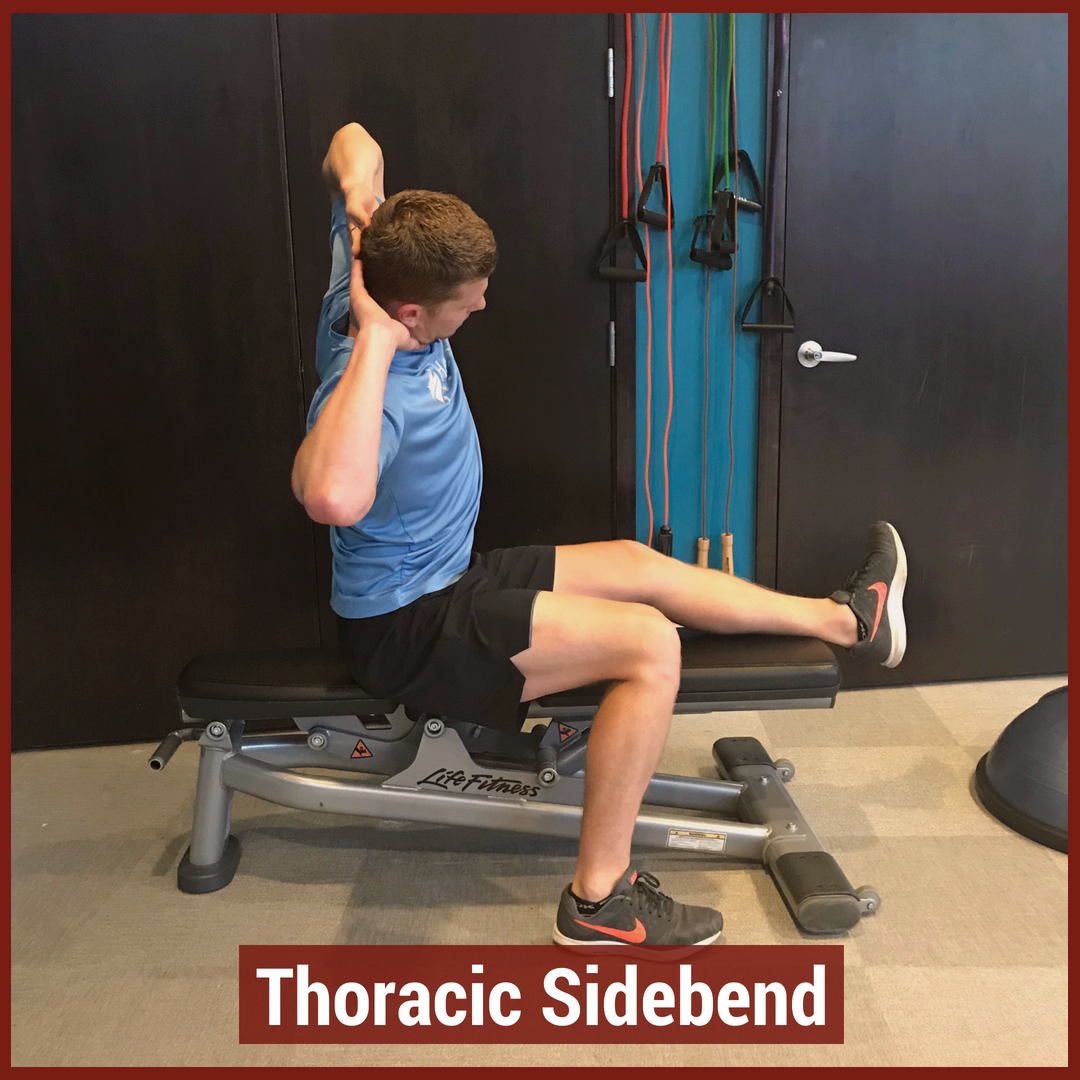

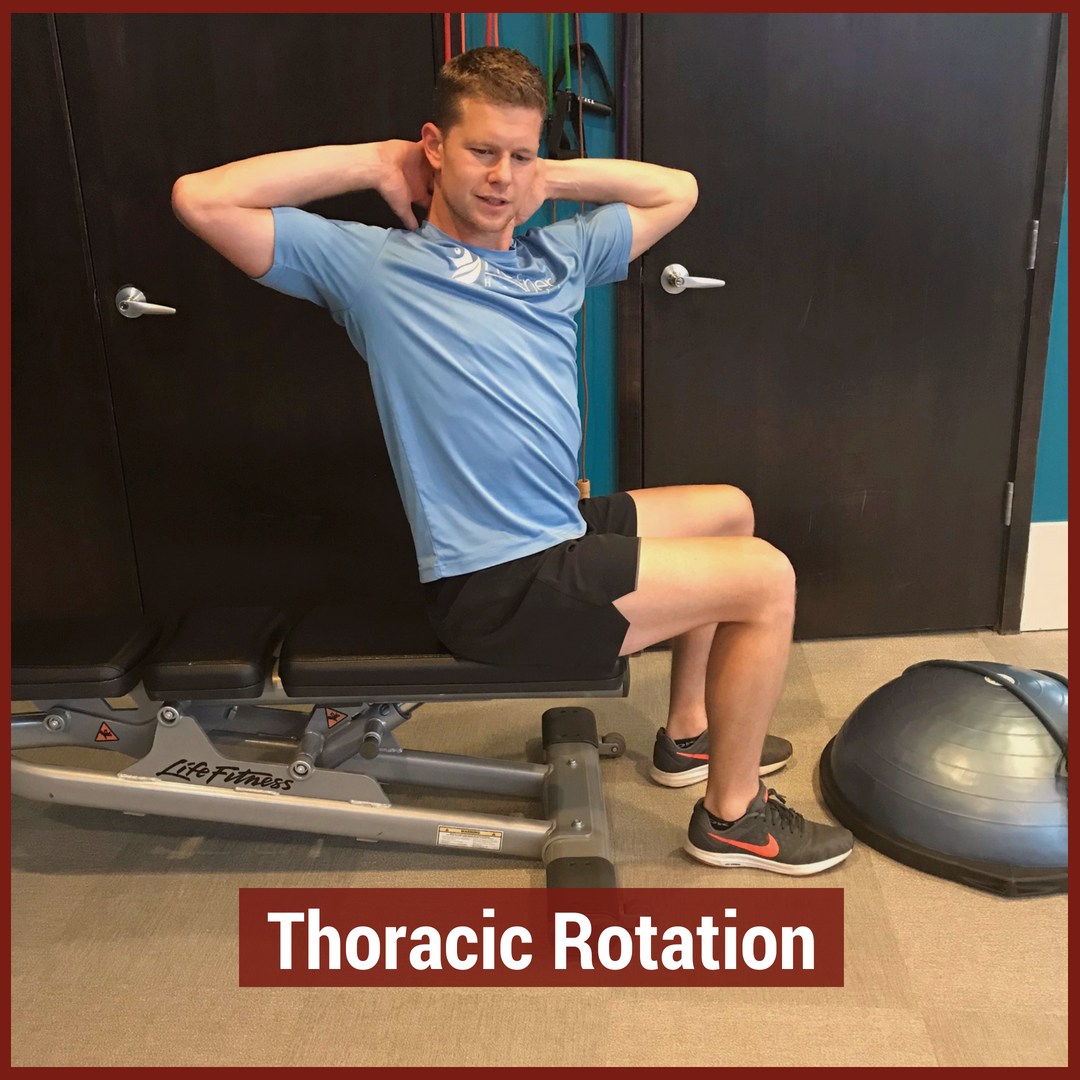

In physical therapy school, the thoracic spine is often glossed over during the musculoskeletal courses. This may be due to the low incidence and prevalence of thoracic spine pain. The incidence of thoracic spine pain is only ~15-19% across the population. This is relatively low compared to lumbar spine pain, which has an 80% prevalence in adults. Additionally, physical therapy schools may choose to emphasize the non-musculoskeletal diagnosis that are important in the thoracic spine. Since many organs are housed in the thoracic cavity, hours are spent on non-musculoskeletal diagnosis. For example, if a patient presents with thoracic spine pain, it is more important to rule-out a myocardial infarction than a thoracic facet restriction. Regardless, there is a gap in student's knowledge regarding thoracic spine anatomy and biomechanics, mobility assessment, and differential diagnosis. In this post, I will be reviewing the active range of motion and segmental mobility assessments for the thoracic spine. Additionally, I have added some clinical pearls for thoracic anatomy and biomechanics! Anatomy and Biomechanics Review The thoracic spine is comprised of 12 vertebrae. These vertebrae have similar characteristics to cervical and lumbar spine- a vertebral body, pedicles directed posterior from the body, lamina that connect to form a spinous process, vertebral facets, and costal demi-facets (Neumann, 2010). The superior and inferior facets of the vertebrae are oriented ~60 degrees from the horizontal plane and ~20 degrees from the frontal plane. Since the thoracic spine connects cervical to lumbar, the junctional regions are important considerations as well. When transitioning from one region, there is no immediate change between cervical to thoracic vertebrae and thoracic to lumbar vertebrae. The superior thoracic vertebrae bare qualities similar to the cervical spine and the inferior thoracic vertebrae resemble the lumbar spine. This may explain why stiffness is often noted in these regions.  Additionally, the thoracic spine houses the sympathetic nervous system. The sympathetic nerve trunk lies anterior to the costotransverse joints. Clinically, this may help explain unusual symptoms that can be reproduced by neural tension tests such as the SLUMP TEST or Straight Leg Raise Test. Sympathetic innervations of the head arises from T1-T2, the upper extremities from T3-T7, the lower extremities from T8-T12 and the trunk from T1-T12. As Dr. Chris Fox wrote in a previous post on thoracic spine anatomy, "In the thoracic spine, T4-9 is known as the critical zone because the vertebral canal is narrowest here; it also has reduced blood supply (Egan et al, 2011). T6 is a tension point; here motion of the spinal core versus canal converge in different directions." Improving the neural mobility in the thoracic spine can help improve movement and decrease pain in the joints above and below. Active Motion AssessmentBelow are descriptions and pictures of thoracic spine active range of motion assessment. While it is impossible to isolate the thoracic spine, certain pelvis and lumbar spine positions can give the therapist a better idea of thoracic motion. In addition to the pictures below, I also assess thoracic flexion, extension, and rotation range of motion in quadruped.

Segmental Mobility AssessmentSegmental mobility is used to determine how much motion is available at each segment. In theory, this assessment is more specific than an active range of motion assessment as it tries to isolate each segment of the spine. While segmental mobility has been shown to have weak inter-rater reliability, practicing the assessment technique can be useful for improving tissue palpation and improving one's hands-on skills. Additionally, this assessment can help guide interventions when clustered with a patient's other symptoms.

Citations:

1. Briggs AM, Smith AJ, Straker LM, Bragge P. Thoracic spine pain in the general population: Prevalence, incidence and associated factors in children, adolescents and adults. A systematic review. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2009;10:77. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-10-77. 2. Ganesan S, Acharya AS, Chauhan R, Acharya S. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Low Back Pain in 1,355 Young Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Asian Spine Journal. 2017;11(4):610-617. doi:10.4184/asj.2017.11.4.610. 3. Neumann, Donald. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System: Foundations for Rehabilitation. 2nd edition. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier, 2010. 322-323. Print. 4. Egan W, Burns S, Flynn T, and Ojha H. The Thoracic Spine and Rib Cage: Physical Therapy Patient Management Utilizing Current Evidence. Current Concepts of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy, 3rd Ed. La Crosse, WI. 2011. Golf is a popular sport around the world, especially in our middle aged and older patients. Due to relatively low contact stresses, the sport is accessible for people of ranging physical capabilities. However, the biomechanics of the golf swing require proper mobility and stability throughout the body, especially at the shoulders, spine, and hips. Many of our wellness clients are golfers who simply want to perform at a higher level on the course. Most of the time, the missing link is unlocking the thoracic spine. Having proper mobility in the thoracic spine can improve the mechanics of the shoulders, low back, and hips. Biomechanical studies of the golf swing have shown a direct link between hip and shoulder rotation. From a structural standpoint, the thoracic spine is in the middle of those two joints and needs to be able to move. Additionally, the sympathetic nervous system is housed directly beneath the middle back, playing an important role in neural mobility. Many therapists prescribe tennis ball and foam rolling tricks for generalized t-spine mobility, but these are often isolated movements. For proper return to sport, therapists must be incorporating movements that engage the thoracic spine, while using the shoulders and hips. Furthermore, without t-spine rotation, the lumbar spine is required to produce more rotation. While lumbar rotation is not inherently bad, dispersing the rotational stresses throughout the spine is ideal. Using combined exercises for improving hip motion AND thoracic spine motion can useful for both rehab and warming up before golf. Below are a few effective treatment options to mobilize the thoracic spine. Spiderman'sTransverse Dowel T-Spine RotationStanding Stork TurnsStanding Step Thru's Exercises for Thoracic RotationHalf Kneeling Thoracic Spine Dowel RotationsInterested in more advanced content for your golfers? Check out our Insider Access!

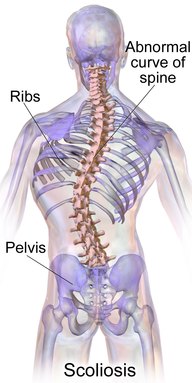

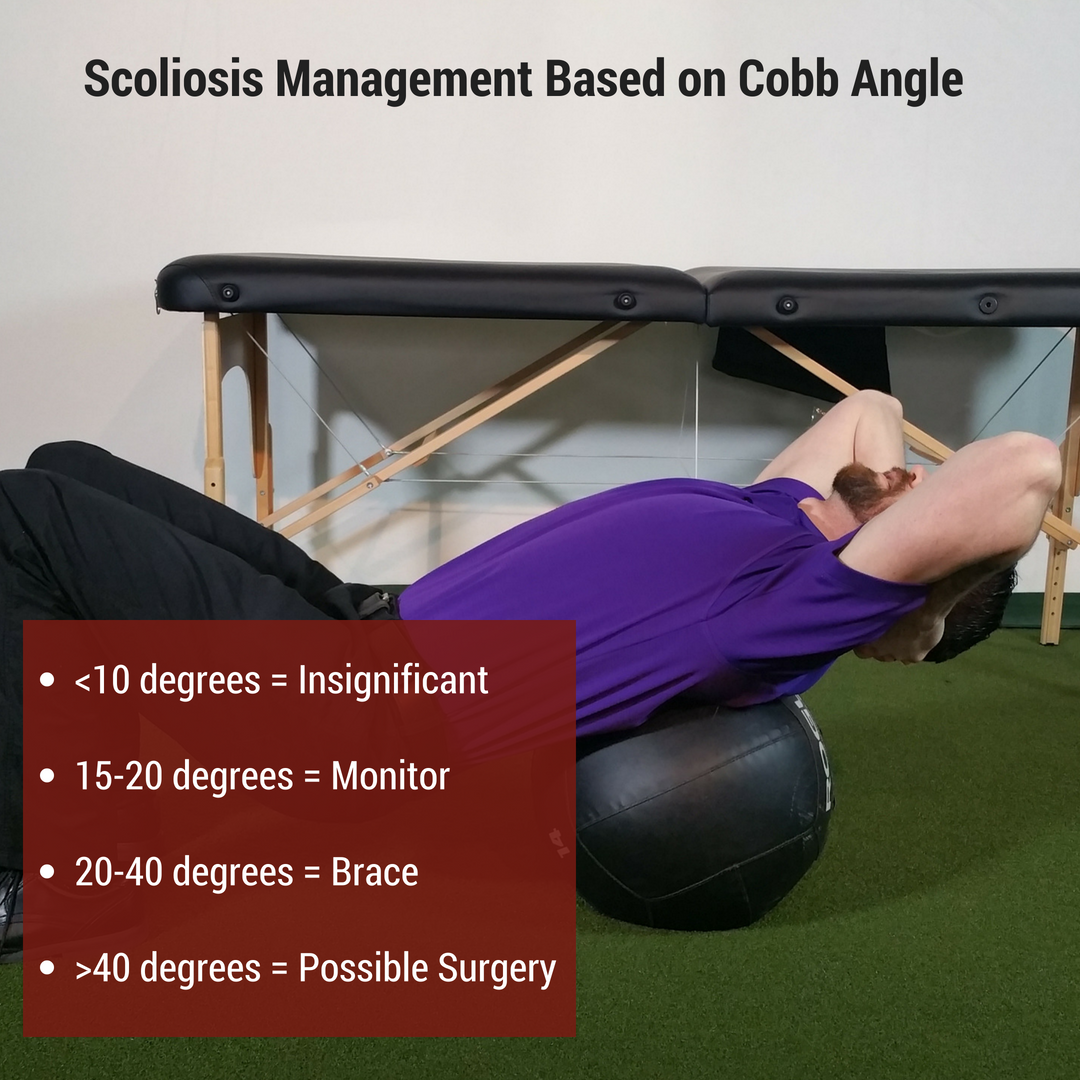

Dr. Brian Schwabe, PT, DPT, SCS, COMT, CSCS Scoliosis involves a 2- or 3-dimensional curve in the spine that can cause visual and/or functional abnormalities. It can involve curves that may go completely unnoticed in some and may impair lung function and daily activities in others. Scoliosis is a condition that has gone through a continuum of "best practice" treatments for decades. From requiring surgery to preventative bracing to minimal management, scoliosis continues to involve different severities of treatment. In PT school I remember learning I had scoliosis after learning how to perform the Adam's Forward Bend Test. I called my mother (a physician) after class to let her know, and she immediately started thinking I needed a consultation with an orthopaedic surgeon. Thankfully, my scoliosis is mild and I am past the developmental stage of life, so it hasn't required any specific management. Different Treatment Options for ScoliosisWhen the scoliosis is severe enough in an adolescent, either a Milwaukee Brace or TLSO (depending on curve location), can be used for treatment to prevent curve progression until the individual matures and the spine is less flexible; however, there are times when surgery is performed due to severity of curve or progression. Yet, when the curve is minimal, it is either ignored, "watched, " or sometimes physical therapy is prescribed (while some advocate exercises to correct imbalances associated with scoliosis, the research has not been shown to correct the asymmetry). Emerging Research in ScoliosisThere are a variety of treatment methods for adolescents with scoliosis, but it is a condition that is managed later in life as well. While some surgeons will perform complex surgeries to correct/prevent progression of the curve, others choose to just monitor (similar to adolescents). However, with more imaging studies being performed, scoliosis appears to present as a possible normal asymptomatic spinal development in many individuals, in regards to its association with pain. Due to these developments, it is likely that a patient may be educated on pain and its lack of correlation with imaging findings. A 2018 article on idiopathic scoliosis found a link between thoracic scoliosis and lung function. In the study, thoracic scoliosis and hypokyphosis was correlated with decreased lung function. This is worth noting due to the importance of normal oxygen levels and proper function of the majority of systems in our body. For example, abnormal lung function may lead to cardiovascular disease. While the study had some faults in design, it should still get us thinking about if we should consider managing scoliosis differently. The first step would be to develop some additional research to determine the validity and strength of the correlation between scoliosis and lung function (and possibly cardiovascular disease later in life). Should the correlation be validated, indications for bracing/surgical/PT implementation would have to be developed. This may be based off measures like pulmonary function tests, Cobb angles, or other findings that can help with decision making on treatment strategies. Regardless, there is still a lot to be done in research regarding scoliosis, lung function, and its impact on mortality, but it may have more significance than we associate with many imaging findings these days. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS Reference: Farrell J1, Garrido E2. Effect of idiopathic thoracic scoliosis on the tracheobronchial tree. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2018 Mar 25;5(1):e000264. Want to learn more advanced information to develop your clinical skills and knowledge? Check out the Insider Access Page! |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed