- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

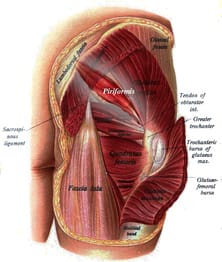

One of the frustrating aspects of research studies that is often overlooked is that patient population, and, more specifically, the diagnostic criteria for that population. Without a specific diagnosis (and conclusive method of diagnosing), the study immeidately presents with multiple confounding variables. Our ability to assess the benefit of an experimental intervention becomes inconclusive when there is a lack of homogeneity in the group. In one of mentoring sessions at Optim, there was a disagreement about pain referral patterns for piriformis syndrome. One individual stated that research well-supported piriformis syndrome up to the spine. I had disagreed as typically pain does not refer that far upwards. Of course, after hearing this disagreement, I went ahead to looked at some of the research behind piriformis syndrome. In this systematic review, the article basically starts out with explaining on piriformis syndrome is a controversial diagnosis and we have little to no clinical ability to diagnose it. Moving onto the actualy results, there was between 14-63% participants with low back pain. Looking simply at the results, it would appear that low back pain is a common finding in those with piriformis syndrome. However, based on the fact that we have difficulty even diagnosing the pathology, we can't rule out the possibility (in my opinion, likelihood) that the lumbar spine may be the source or the primary component (think Double Crush Syndrome). This conflict should basically have stopped the study as all findings, in reality, have fault in basis. So what does this mean clinically? For me, not much. I treat the impairments primarily in my patients. If a patient did come in with "piriformis syndrome," I'm going to address any lumbar mobility restrictions I find. If the hip is weak, I'm going to strengthen it. That be said, there are some conditions where specific diagnoses do have clinical impact. For example, if a specific diagnosis has been shown to benefit significantly from a particular intervention, that will absolutely be included. In most cases, we need to be more critical analyzing all aspects of the article, especially the population/diagnostic criteria before we implement the results in our practice. Evidence-informed, not evidence-restricted. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS Reference: Kevork Hopayian,1,3 Fujian Song,1 Ricardo Riera,2 and Sidha Sambandan1. The clinical features of the piriformis syndrome: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2010 Dec; 19(12): 2095–2109.

2 Comments

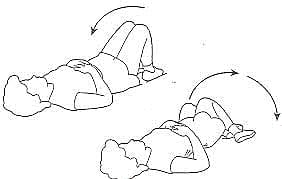

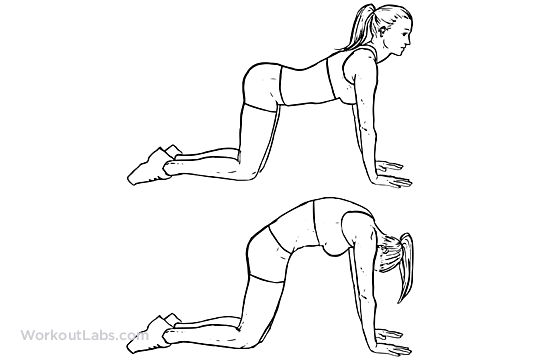

There was a time in my career when I thought general mobility exercises were practically malpractice. For those of you who are uncertain to which exercises I am referring, it was exercises like lower trunk rotation and cat-camel type of exercises that just encourage general mobility in all directions. At the time, my background in Sahrmann's Movement Impairment Syndromes (MIS) is what drove my preference for avoiding lumbar mobility exercises. If you are unfamiliar with Sahrmann theory, she believes that loss of mobility and development of pain stem from abnormal repetitive movements and prolonged postures that lead to repetitive microtrauma. Should a patient fall into a MIS category, the treatment plan would be to work on core stability, while challenging the spine through different levels of stress in various movements. For example, if a patient has lumbar extension syndrome, we would focus on keeping the spine in neutral while moving towards hip extension. For a better understanding on MIS, I recommend either checking out a Lumbar MIS lecture I gave last year or reading Sahrmann's text books. While I continue to practice with components of Sahrmann theory, I believe general mobility training can play a role in pain modulation. As many of you are likely aware, the development of pain science research has shown there to be a significant lack of correlation between pathological findings (on imaging) and pain. Many patients that come into our clinics with low back pain have either a fear of movement in one or multiple directions or are unaware of how to achieve those movement directions or positions. Exercises that encourage mobility in various directions can play an essential role in addressing the sensitivity of the nervous system and thus pain. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

I recently had an individual with low back pain for an evaluation who reported she has a history of being "hypermobile." Upon further questioning, she revealed a family history of Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (EDS). While the patient had never been diagnosed with any hypermobility disorder, I assessed her mobility using the Beighton Sign of 9, due to the genetic factor of EDS and the effect it has on collagen. For those of you unfamiliar with the Beighton scoring system, mobility is assessed at several different points (such as elbow extension, knee extension, lumbar flexion, etc.) for excessive motion. These patients will displays genu recurvatum, hyperextension of elbows, and hands flat on the floor with lumbar flexion. She was positive in all of the factors I assessed. In hypermobile individuals, we should expect excessive mobility in all directions for each joint. When I looked at my patient's lumbar mobility, she had what would appear to be "normal" or a mild loss of mobility in each direction. Without knowledge of the presence of hypermobility, we might develop an inappropriate plan of care. Typically, when we think of people with hypermobility, we immediately assume we have to assign these individuals to a stability-type program. However, patients generally with hypermobility can present with relative hypomobility following an injury. My particular patient had a traumatic even at work and met most of the criteria in the lumbar mobility treatment-based classification. I initiated lumbar mobilization and AROM exercises with some repeated motions for HEP. She has shown significant improvement thus far with the emphasis on restoring her to her "normal" hypermobility. That is not to say she doesn't require any form of stability training. Once this patient's mobility has normalized, I will redirect my plan of care to retraining movement patterns and building strength and power on them to help build her functional stability. The primary take away is that, given the circumstances, any individuals can fall into a mobility treatment plan, even hypermobile patients. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

Those familiar with implementation of repeated motions are likely familiar with the benefit of using tibial internal rotation (IR) to improve lower quarter dysfunction. However, the majority of clinicians associate press-ups with repeated motions and are unaware of how to use the technique with the extremities. Each joint has a "common reset" that can be used to improve both pain and mobility. These patterns are based on common dysfuntional presentations but are by no means a rule. While the majority of injuries will respond to some sore of repeated motion, it may take time and there are some occasions where a joint may not respond. One of the common resets for the knee is tibial IR. As many of you are aware, the arthrokinematics of the knee include tibial rotation during sagittal plane motion. As the knee extends, there is a slight ER of the tibia that occurs to help lock it out. As the knee flexes, the tibial slightly internally rotates. When injury occurs to the knee, we often see a loss of one of these rotation motions as either end-range knee flexion or extension is affected. Thus, the repeated motion for limited tibial IR is closed-kinetic chain (CKC) knee flexion repeatedly while manual overpressure is applied into IR. While this exercise is obviously beneficial for knee disorders, it can also be implemented with foot/ankle dysfunction. Limited CKC ankle DF has been shown to be associated with excessive tibial external rotation (Rabin et al, 2016). This likely being associated with limited tibial IR mobility. Utilizing this same exercise (or something that similarly addresses decreased tibial IR) for limited ankle DF ROM can improve functional CKC mobility. Part of the reason for this benefit may be due to abnormal foot/ankle movement patterns. For example, take a look at an excessively prontated foot. As this ankle moves into DF, the motion prefers to come from the talonavicular joint or somewhere distal. This pattern leads to an abnormal utilization of tibial internal rotation at the knee. By maintaining subtalar neutral while moving into CKC DF with tibial IR overpressure, we may theoreticlly be mobilizing part of the talocrural capsule that is typically restricted and forcing a prontation motion. With the association shown between limited ankle DF mobility and hip/knee problems, it is well worth examination in all lower quarter patients. Try checking your patients ankle DF mobility in CKC for the next couple weeks and look for any abnormal movement patterns. See if you start to notice some patterns. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS Reference: Rabin A, Portnoy S, Kozol Z. (2016). The Association of Ankle Dorsiflexion Range of Motion With Hip and Knee Kinematics During the Lateral Step-down Test. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2016 Nov;46(11):1002-1009.

|

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed