- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

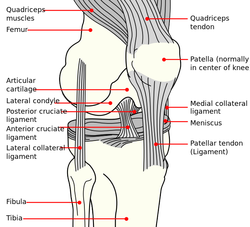

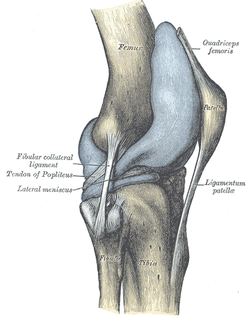

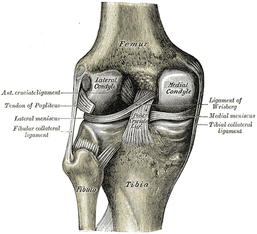

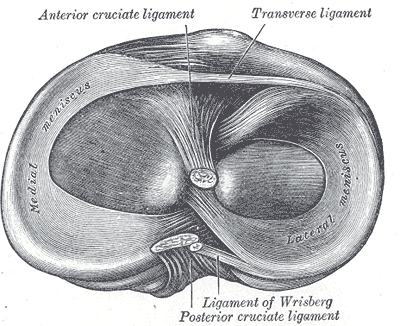

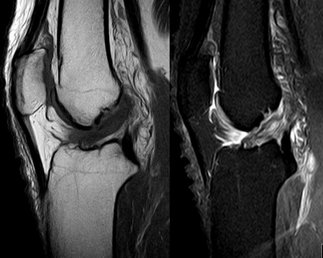

My Conservative Management of a Medial Collateral Ligament Ligament Injury: Advice and More6/13/2014  This post was inspired by a personal injury I sustained ~6 weeks ago. The nature of the injury will remain disclosed as it was a rather embarrassing traumatic event. Regardless clinical tests and measures ruled in a low/medium grade Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL) injury. With the help of some colleagues and personal knowledge, I have been self treating the injury and want to give some personal feedback regarding the process. Below are 5 key points I will touch on from a patient perspective: 1. The acute pain is real- it must treated before we can address other impairments. It is most important during the acute stage that the clinician rule-out complete ligament rupture and/or neurovascular damage prior to addressing other impairments. For 3-5 days following the injury, I would experience sharp pains with knee flexion and extension. During this time period, all provocation clinical tests were positive: McMurray, Valgus Stress Test, Apley's Compression and Distraction. Performing rotational movements such as getting out of the driver's seat of my car seemed impossible. This movement is essentially performing a self Thessaly Test. So why were all tests and measures positive? Following a knee injury, pain and swelling surround the knee make all movement painful. Swelling moves to the path of least resistance, which is located inside the joint. Additionally, it is important to look at the anatomy. The MCL has attachments into the medial meniscus, posterior-medial joint capsule, and semimembranosis tendon. The proximity of these structures can cause significant shearing to the entire area which confounds the results of the physical examination. Managing the acute pain quickly and effectively is extremely important to progressing the rehabilitation. 2. Restoring the normal joint kinematics, ROM, and muscle function is key. Following a knee injury several key impairments exist that need to be managed early in the rehabilitation process. As I stated above, addressing the acute symptoms of swelling and pain are necessary. Significant flexion and extension ROM deficits will exist and quad lag will be present. Management of these symptoms is basic, but the importance can not be understated. Since the injury, I have been much more adamant with my patients about performing heel slides, quad sets, short arc quads, and allowing me to perform tibiofemoral mobilization and manipulation. Before the injury I discredited the importance of such simple movements. One exercise I often prescribe is a heel slide + quad set combo to get a quadriceps contraction, allow for the screw home mechanism to work, and also reach full flexion in the same exercise. These exercises are relatively boring and simple, but boring does not mean unimportant and that message needs to be translated to your patients. Restoring these basic impairments- ROM, quadriceps strength, and accessory mobility- must occur before higher level strengthening and dynamic movements are brought into therapy. 3. Performing the home exercise program is not enjoyable, but it is necessary. As stated above, the early HEP is not fun and often temporarily causes increased discomfort (similar to pain) and swelling following excess movement. Anatomically speaking, discomfort is expected. Throughout knee ROM different portions of the MCL become taut. In full extension, the posterior fibers are taut and during flexion, the anterior fibers become taut. We are stressing the disrupted tissue during our HEP, but it is gentle stress which helps restore normal tensile forces to the ligament. Think about the effects of Exercise and Tissue Healing. For the first few weeks I would joke that it felt as if I had knee arthritis. The knee was very stiff in the morning with initial weight bearing and loosened within the first few steps. The pain and stiffness was related to residual swelling stuck in the knee. Personally I neglected flexion range of motion early because of the discomfort I felt during the movement. Now I am still feeling the effects of not reaching this range earlier during the rehab. The HEP needs to be performed early and often.  4. Do not do too much too soon. Within 3 weeks following the injury, I had "acceptable" ROM and almost full quadriceps strength and good hip strength. I had been biking for 75+ minutes at a time and was mentally exhausted from having a knee injury. I wanted to return to my prior level so I did- or at least tried to. At week 3 I returned to performing light weighted squats, running short distances, burpees, and more. This was unsuccessful. "Acceptable" ROM and almost full quad strength will not work. My body was compensating for these impairments by using the other limb greater and substituting where ever possible. I was having muscle soreness and aches in my other hip and low back. Despite these aches, I continued to load the joint abnormally, hoping the discomfort would subside. After 1-2 weeks of this exercise, my knee was just as stiff and now noticing a clicking with end-range flexion. Naturally, I was thinking an added mensical injury- pain with flexion OP, pain with extension OP, joint line tenderness, positive McMurray, and clicking and popping into flexion. Fortunately, I did not have any joint locking. I need an X-ray or MRI right? Not so fast. After resuming my prior HEP and receiving some advanced manual techniques in clinic, all of my symptoms except pain with flexion overpressure have diminished. Before jumping to any conclusions regarding imaging or surgical options, allow yourself to restore the normal joint mechanics and see what happens. I may have a partially torn meniscus, but am I a surgical candidate? What would imaging show me that would change my plan of care at this point? When working with your patients, respect the tissue healing process and use the exercise progressions and available return to sport criteria before letting them jump into full activity. 5. There will be Ups and Downs during the rehab process. I am now six weeks into my rehabilitation and things are going well. Things have not always gone well though. I became frustrated several times during the process which has slowed down my return to activity. Do not test the gods of tissue healing because they will win. The body has a natural process it must go through following injury. Final words of advice: start simple, restore normal anatomy, and use clinical judgment and any available tools for exercise progression. -Jim

1 Comment

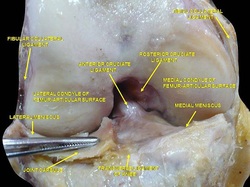

Following reconstruction of the ACL, there is a level of fear associated with re-injury. Not only does this anxiety increase injury risk, but it also lowers the level of performance. The Chicago Bulls' Derrick Rose has been under criticism, regarding this issue. In April 2012, Rose tore his ACL and went on to have surgery about a month later. Around March of 2013, his surgeon said he was medically cleared to play. Rose then went back and forth about being ready to play until the playoffs were over. His reason for hesitancy was lack of confidence in his surgical leg. Physiospot did a review of some research on this topic. It was found that only 31% of athletes return to pre-injury level of play at 12 months. An association was found between pre-surgery/early rehab psychological response and return to pre-injury levels at 12 months. We should take two things away from this: at this point, it is the exception, not the rule, that athletes return at pre-injury levels at 12 months or fewer, and we should be assessing the psychological component in rehab more often. Another item to point out, is the fact that we, as a health care system, are lacking any truly valid return to play criteria for ACL reconstruction. Many surgeons/physical therapists use things like isokinetic strength testing compared to the uninvolved limb, but as you can see by the 31% level of return, there is a discrepancy between isokinetic strength and actual competitive play.  If you feel like we having been referencing The Gait Guys a lot recently... it is because we have! They have put out a few great segments recently including this 2 part series on the Power of Observation. As clinical novices, we often do not have enough opportunities to see pathological gait patterns and conditions. As former students, almost of our lab "patients" were healthy classmates. While those experiences were rewarding, they were far from a real situation. In this series, Shawn and Ivo dissect a triathlete's gait pattern. The patient presents with chronic low back pain, but has impairments throughout the entire lower chain. One interesting impairment they discuss is a "clenched fist on the L," which they attribute to flexor dominance and related to decreased arm swing and proprioceptive deficits. Their explanation: the proprioceptive system feeds the cerebellum. The cerebellum helps fire axial extensors. Because proprioception is limited in this athlete, the patient is naturally drawn into a flexor dominant position. Check out the entire post to gain more gems like this one! Because the gait guys use a Tumblr format, you may have to scroll down to June 25 and June 26. Enjoy!  Plica! I am sure you have heard of them, but do you know the likelihood of one of these patients showing up at your clinic door? Should you consider any special treatment recommendations with this population? Keep reading to find out! Plica are inward folds of the synovial lining of the knee. Because they are embryonic deviations, plica are seen inconsistently throughout the population. Typically, they do not cause any pain and are asymptomatic, but they can become inflamed resulting in a "plica syndrome." From a clinical standpoint, it is important to note that "symptoms...are indistinguishable from other intra-articular conditions such as meniscal tears, articular cartilage injuries, or osteochondritic lesions, creating a diagnostic conundrum." There are 4 general categories of plica: suprapatellar, medial parapatellar, lateral, and infrapatellar. Lateral plica are very rarely seen and consequently little research has been conducted on them. Classification of each other type of plica becomes confusing because each one has multiple sub-groups. It is important to know that the suprapatellar plica does have attachments to the quadriceps tendon and depending on the size and shape, may create impingement between the patellar tendon and femoral trochlea in the range of 70-100 degrees of knee flexion. Similarly, the medial patellar plica also changes orientation with different positions of the knee. Its origin and attachment is controversial with several authors listing different anatomic variations. Finally, the infrapatellar plica is the most common plica in the population with 85% of patients presenting with one according to a study by Wachter in 1979. It runs superior-inferior from the intercondylar notch into the infrapatellar fat pad. The incidence of individuals with plica syndrome is under controversy, and some surgeons believe it is over-diagnosed. Clinically, 50% of patient's with plica syndrome will have a history of trauma or twisting at the knee joint. Once the initial injury is resolved, a patient maybe asymptomatic for a period of time, only to report back to the clinic weeks or months later with intense anterior knee pain. Anterior knee pain is known as the cardinal symtpom regardless of which plica is affected. Additionally, they may have complaints of a clicking or popping in the knee with flexion and describe the pain as intermittent, dull, and achy. Others report a tightness around the anterior medial knee joint which increases with deeper knee flexion angles. Because the incidence of plica syndrome is low, diligent differential diagnosis is a must, ruling out other possible causes of anterior knee pain. A clinical diagnosis alone is very difficult. Recent studies have shown the both MRI and Ultrasound have had good success in viewing plica shape and size. So what can we do for these patients? Unfortunately, "success rates of conservative management are generally low" with age being a predictive factor for your success. The younger patient is more likely to respond favorably to conservative treatment since they have not suffered the long-term effects of impinging plica and resulting structural changes within the knee joint. Therapy should consist of a period of rest from deep knee flexion activites, followed by a course of NSAIDs to help curb inflammation. Caution should be taken with intense exercise progression secondary to likelihood of aggravating the plica. Additionally, success rates of PT alone are variable and surgical intervention may be required with persistent symptoms. It should be noted that while this is a recent article, many of the references under conservative management are fairly dated. The therapy profession has since grown in its knowledge of conservative treatment for knee conditions and the importance of regional interdependence around the knee joint. In conclusion, plica syndome is not something you will see in the clinic everyday, but having this knowledge in your toolbox will make you a more well-rounded clinician. Reading this article would be very beneficial because there are great pictures discussing different variations and anatomic location. References:

Schindler O. 2013. 'The Sneaky Plica' revisited: morphology, pathophysiology, and treatment of synovial plicae of the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013; 2013. Web. 14 May 2013.  An article, discussing a new test for meniscal integrity, was recently brought to our attention. As you know, there is only one single-test for meniscus tears that has adequate diagnostic accuracy: Thessaly Test. It has a sensitivity of .89 and specificity of .92. The issue with this technique is that it can increase the tear (the test actually mimics the mechanism of injury). Another common test we see is Joint Line Tenderness, but this test has a sensitivity of .63 and specificity of .77. While this test alone is insufficient, when clustered with several other tests, the diagnostic accuracy greatly improves. The cluster includes: history of joint locking, Joint Line Tenderness, McMurray's Test, pain with flexion overpressure, and pain with extension overpressure. The article we looked at discusses using Joint Line Fullness as a clinical test. The patient is supine and the examiner palpates along the affected joint line to compare fullness to the uninjured side. If the joint line fullness causes a loss of joint compression, the test is positive. The lateral side of the knee is examined in 30-45 degrees of knee flexion to slacken the IT Band, while the medial side of the knee is examined at 70-90 degrees of knee flexion to slacken the MCL. The test had a sensitivity of .70 and specificity of .82. Again, by itself, this test's accuracy is still lacking. One might argue that it could potentially replace Joint Line Tenderness in the cluster to increase the diagnostic accuracy even more, however, we must look at the methods of the study first. The study excluded any patients with an acute injury (within 6 weeks of exam) or presence of osteophytes, joint space loss, or arthritis. Due to the fact that we often see our patients in the acute stage within 6 weeks of injury and frequently our patients have arthritis, the findings of this study become questionable. If many of our patients are bound to have the exclusion criteria, will the test still prove useful? Now, we are not suggesting that the test has no usefulness, but perhaps an additional study should be performed, where these patients are included. Reference: Couture JF, Al-Juhani W, Forsythe ME, Lenczner E, Marien R, Burman M. (2012). Joint line fullness and meniscal pathology. Sports Health. 2012 Jan;4(1):47-50. Web. 14 May 2013.

In regards to the nerve supply, the "nerves" often proclaimed as supplying the VMO or VML have been shown to be partitions of the femoral nerve to supply distal motor units, sensory nerves of the saphenous nerve, or nerve supply for the knee capsule. Additionally, let's take a look at the claimed function of the VMO: medial patellar tracking. No one has ever been able to demonstrate isolated medial patellar tracking. Many of the studies cited in this article are outdated. We are not disagreeing with the fact that different parts of the muscle have different proportions of fiber types, but we cannot come to the same conclusion of the significance of these findings. What are your thoughts on this recent article?

This is a good, quick 7-minute TED Talk given by the orthopaedic surgeon, Dr. Kevin Stone. He presents several interesting concepts and innovative strategies about the future of joint replacements. This might not be something you see in your clinical practice today, but as science continues to improve Dr. Stone's biological approach to joint replacements could be something you see on a more regular basis. Check it out!

|

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed