- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

Recently, The Manual Therapist wrote a blog post about what is most important when treating a patient: the what, the why, and the how. To relate it more directly, what you have refers to specific diagnoses. Why you have it refers to the theory of why the pathology occurred, i.e. movement impairment syndromes. The how refers to how we actually treat and assess. Much of medicine and physical therapy is often stuck in the "what" phase. We tend to assign diagnoses to tissue pathology and often look to treat what we believe is the source of the pain, not the original cause. Many physical therapists are moving towards the "why" mindset where we look at a more complete chain of the body to determine why our patients are in pain. This typically leads to a more well-rounded treatment approach. The "how" comes back to what we are actually doing and how we are treating our patients. I recommend reading the original post by Dr. E to get further clarification. This post comes with good timing in the wake of Tiger Woods' "sacrum" comments. In case you missed it, Tiger Woods recently played in a golf tournament and had to withdraw, because he claimed his "sacrum went out." As a result, there was a backlash from much of the young PT community claiming how it was a horrible diagnosis, Woods' physical therapist had poor communication skills, etc. The discussion lead to many physical therapists and physical therapy students ranting about how the research for SIJ Dysfunction as a diagnosis is poorly supported based on higher level evidence (which is correct) and some even saying how the SIJ doesn't move at all. Based on these comments, it would appear many do not assess or treat the Sacroiliac Joint. While I may agree that we shouldn't worry about actual tissue diagnoses, I get frustrated by people's reluctance regarding any potential SIJ treatment given my personal clinical success. In the residency at Scottsdale Healthcare, we were taught various assessment and treatment techniques for the SIJ, but the distraction manipulation could be used as a "shotgun" approach and treat typically any form of SIJ dysfunction. In my limited experience, in the patients I feel would benefit from the manipulation, they tend to be 100% within just a few visits. Now a manipulation by itself is never the answer alone, but it can be an extremely useful tool. We need to build on preventing future recurrences of pain and teach our patients to maintain improvement independently. Some patient's arrive at clinic in excruciating pain and are nearly pain-free after manual treatment. A manipulation and mobilization are not the only potential treatment for what some would diagnose "SIJ Dysfunction." Repeated motions towards the directional preference may be appropriate as well. Basically, many of treatment techniques like these have theories to support them, but the evidence is not always as established. That doesn't mean successful treatment techniques should be discounted. I again recognize our limited ability (and importance) of truly diagnosing what we think we see with the SIJ, but I must continue to stress the impact of when we assess, treat, and reassess. This is the importance of the how I discussed at the beginning. If the patient feels better immediately after a treatment technique, something I did had the desired effect! We currently are unable to be certain in knowing the exact mechanism our techniques have, but we should not ignore positive results. I have written extensively in the past about the problems with the studies regarding manual therapy, especially the SIJ, but that is not important in the end. What is important is that we find effective ways in getting our patients better as soon as possible. If that means doing a manipulation or mobilization where we think we are targeting the SIJ, then so be it. Do not let the limitations in higher level research prevent you from providing your patients with the most effective care. -Chris

17 Comments

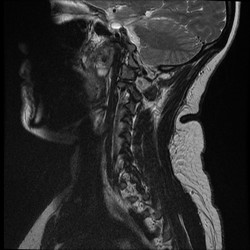

In school, many students are taught about the clinical significance of imaging, but how many end up utilizing it clinically? It seems like I rarely go a day when I don't hear a patient or clinician mention how bad the patients' MRI findings are and how that is the reason for the patient's symptoms. "So and so blew out a disc lifting a heavy box," "I have 3 slipped discs in my neck," or "the MRI revealed impingement at C4." The list goes on and on; however, my personal favorite is "my knees are bone on bone!" Sure the MRI can pick these things up, but do they matter? While I support the use of imaging to help rule out various non-musculoskeletal pathologies and life-threatening symptoms, there is quite a bit of evidence that says we should not rely on imaging for things like determining the significance of herniate discs, stenosis, bone spurs, and more (Boden et al, 1990 & Jensen et al, 1994). What these studies reveal is that quite a few people without any symptoms or complaints have the same MRI findings as those with pain. What does this mean? While it is theoretically possible that findings like stenosis, bone spurs, and discs can create various symptoms, just because we see something on an MRI does not mean that it is the source of our patient's symptoms. This is why I get frustrated when I hear patients (or PT's) start to list off their findings or when patients and health care practitioners are pushing for surgery. As clinicians, we should regularly educate our patients on just how insignificant some imaging results can be in regard to orthopaedic complaints. What we have discussed thus far does not even touch upon our understanding of modern pain science. Having recently completed Butler and Moseley's Explain Pain, my understanding of what "pain" actually means and how it develops has changed drastically. We don't actually have pain receptors. We have an intricate system of "danger" (noci-) receptors. This system is influenced by different cultural upbringings, our surroundings, and much more. It can even adapt to affect and be affect by other parts of the nervous system! What we feels as pain often occurs for a reason, to warn us. However, the nervous system can become hypersensitive and lead to various types of chronic pain. Think about diagnoses such as Chronic Regional Pain Syndrome. These patients actually visualize the affected body part as being enlarged! How is it that someone with horrendous pain from a "blown disc" can immediately get near 100% within a couple days with something like repeated motions? We aren't pushing the disc back into place; we are affecting the nervous system! This ties right back in with abnormal imaging findings. We cannot let the results of an MRI impact our clinical decisions and treatments based on this. I am not advocating against the use of MRI's (or other types) in general, but I believe we do a disservice to our patients by biasing their mind with MRI results before even giving therapy a shot. This thought process alone can affect how the patient perceives their disability and affects the function of the nervous system. With the right treatment technique (repeated motions, manual therapy, chronic pain education), most patients should see improvement. -Chris Reference:

Boden SD1, Davis DO, Dina TS, Patronas NJ, Wiesel SW. (1990). Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990 Mar;72(3):403-8. Web. 24 Aug 2014. Butler D & Moseley L. (2013). Explain Pain: 2nd Edition. NOI Group. 2013 Sept. Print. Jensen MC1, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian D, Ross JS. (1994). Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994 Jul 14;331(2):69-73. Web. 24 Aug 2014.  Pain science is becoming a more important aspect of physical therapy training. Many schools are not dedicating enough time to understanding how and why pain operates and persists. Fortunately, there is a wealth of resources on the internet to help supplement what is being taught in physical therapy education. On the TSPT blog, we have discussed this topic several times. (Here and Here). Recently, I stumbled upon this video produced by Brett Peterson, MPT, OCS, FiT on the PT Coop website. His video outlines: a) A brief history of the past and current pain theories b) Psychological components of pain c) Perception and the relationship to pain d) Treatment options for physical therapists

The next issue is the lack of research on exam measures and intervention techniques that we use in the clinic. We have had our mentors and fellow clinicians comment on where the evidence is for some of our treatment styles. A perfect example is Instrument Assisted Soft Tissue Mobilization (IASTM). While there is some initial research out there currently, there is hardly enough evidence to prove that IASTM is a high-quality, proven treatment. That being said, the results can be impressive. The key comes back to test and re-test your patients after a treatment. This applies to more than just IASTM. With your corrective exercises, joint mobs/manips, etc., assess your patient first (pain, ROM, strength, symptoms, SFMA) and re-check afterwards. Going back to IASTM, we have had particular success improving ROM without neural provocation using IASTM. Utilizing the neural tension test as our base and then follow-up, we have seen gains in ROM by as much as 45 degrees after simply a few minutes of IASTM. Basically, if you can prove that a treatment works by doing this, why stop it? Of course, we can't forget about incorporating these changes into our care and reinforcing them to lock in the changes, but the lesson is we shouldn't limit ourselves by what the literature is (or isn't) saying at the time.

Outcome Assessments! In school we learned hundreds of different outcome measures: Measures for Fear Avoidance, Fall Risk, Disability, Quality of Life, and more. Everyone hears about them, but who actually uses them? According to a study by Jette et al, 48% of therapists used standard outcome measures. Personally, we thought this figure was slightly ambitious, but the even more unfortunate figure was that of the 52% of participants who did not use outcome measures, 49% stated they did not intend to incorporate them into their clinical practice in the future. Reasons for the lack of participation included the measures are too time consuming, too difficult for the patient to fill out individually, and too time consuming to analyze and calculate the results. While we do not agree with these excuses, we do understand the added workload in using certain Outcome Measures. Let's not focus on why we do not use them, but rather point our attention to why we should incorporate them more regularly. First, they can be an excellent tool to give the practitioner objective data that he/she can utilize in goal setting and prognosis. The assessment will paint a clinical picture of the patient's functional ability and open up communication between the PT and patient to discuss how the patient perceives his/her current status. Second, payers want to see them! Even if you are not satisfied with using them, CMS for example is "recommending" that patients fill particular outcome measures that directly link to functional limitations. The guidelines with which we get reimbursed are becoming much more stringent. These assessments are an objective means of showing improvement. Whether you like it or not, our field is progressing to a pay-for-outcomes profession. Finally, if we ever expect to gain autonomy in clinical practice, we need to show consistent objective data that our treatments have a true impact on the patient's function. Currently there are several very sophisticated outcome measures, such as FOTO, that give you information about a patient's fear avoidance, expected number of visits, expected improvement, and more. We need to continue to use these measures to standardize practice! As we mentioned at the beginning, there are hundreds of different outcome assessment to choose from. Memorizing them would not be beneficial. Rather you should know where to find them and how to interpret them. The following are two great resources that give you access to a number of familiar (and some unfamiliar) assessments you are likely to encounter. Rehabmeasures.org Physio-pedia.com  While relatively new to the field of Physical Therapy, Clinical Prediction Rules have been used in medicine for a very long time (for example the Deep Vein Thrombosis CPR). These rules have been designed to improve clinical decision making and assist the practitioner in diagnosis, prognosis, and intervention planning. Childs and Cleland point out that "CPRs provide practitioners with powerful diagnostic information from the history and physical examination that may serve as an accurate decision-making surrogate for more expensive diagnostic tests." Not only can CPR's help curb the rising costs of healthcare, using this high level of evidence is especially important in the direct access setting where more extensive diagnostic testing has not been performed. In addition to diagnosis, other CPRs can aide in the classification and subgrouping of patients to guide you in intervention planning. Now that you know CPRs are important, what are these clinical prediction rules and where can you access them? Fortunately John Synder at the Orthopedic Manual Therapist recently compiled a list of them. Check them out HERE! References:

Childs J and Cleland J. (2006). Development and Application of Clinical Prediction Rules to improve decision making in Physical Therapist Practice. PHYS THER. 2006. Jan;86(1):122-131. Web. 13 Aug 2013.  As evidence-based practice is becoming a staple in physical therapy education, it is important we properly assess each piece of research before choosing whether or not to incorporate its findings into our practice. Given the breadth of science courses that consume most of our schooling, non-clinical classes like evidence-based practice often get set aside as less important. Unfortunately, we often fail to realize the significance of search strategies, article assessments, and more when we are in the didactic portion of school. Instead, this material should really be one of the largest emphases in our programs, due to the need to stay up to date with best practice methods. With the NPTE and clinical work coming up soon, we thought it would be a great time to review some of the core components of EBP. This review is by no means exhaustive, but instead is intended to give you a foundation for further review. CONTINUE READING.... |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed