- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

|

This is a a great video review by The Sports PhysioTherapist on Juvenile Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee. Check out his website for some great information!

0 Comments

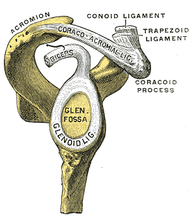

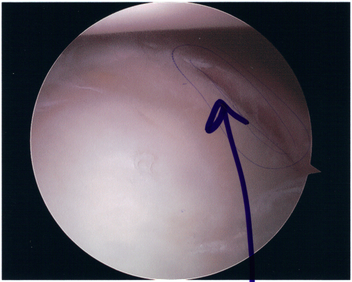

After 10 years of campaigning, the Chartered Society of Physiotherapists was granted the right to prescribe "any licensed medicine relevant to their particular scope of practice." UK physiotherapists will be able to prescribe medications for conditions such as asthma, neurological conditions, rheumatological conditions, pain, and more. The article does make a point to say only those with an "advanced practitioner degree" will be able to practice the new changes. This new responsibility is a HUGE step for physical therapists around the world. It demonstrates that years of perseverance can lead to change. This should be motivation for us to continue to practice highly skilled interventions and work towards true autonomous practice.  There is an endless amount of shoulder tests, many lacking any diagnostic accuracy. Mike Reinold, one of the authors of The Athlete's Shoulder, presents two new tests in this article to detect SLAP lesions: the Pronated Load Test and the Resisted Supination External Rotation Test. He provides a description and video review for the tests, along with some evidence. Additionally, he links to a few other posts of his on SLAP lesions, including classification, injury mechanisms, and examination. He is in the process of developing a related post on the rehabilitation of SLAP lesions. Check out the article to add a few new tests to your tool belt! Pathophysiology: In 1980, Neer and Foster first coined the term multidirectional instability. They defined it as uncontrolled and involuntary subluxation or dislocation in the anterior or posterior direction of the shoulder. The primary pathology involved can have many potential contributors: excessive capsular redundancy, laxity due to increased elastin density and decreased collagen density, poor osseous configuration such as a flattened glenoid fossa, or weakness in the glenohumeral and scapular musculature that results in poor neuromuscular control (Andrews, Reinold, & Wilk, 2009). Understanding the primary constraints to these movements allows the clinician to have a better understanding of which ligaments and muscles are not functioning properly in MDI. There is little bony stability at the glenohumeral joint and therefore muscles and ligaments act as the primary supporter of the shoulder. Muscle activation patterns have been shown to be different in those with congenital instability compared to normal individuals; the normal force coupling that occurs is absent and the humerus has excessive translation during shoulder movements. There is some debate in the academic community about whether the abnormal muscle patterns are the cause of shoulder instability or shoulder instability leads to abnormal muscle patterns. Recent research is leaning towards the latter. The main structure resisting excessive anterior translation of the humeral head is the anterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL). Weiser et al. found that scapular protraction places increased tension on the anterior band of the IGHL. The main restraints regarding posterior instability include the posterior band of the IGHL and the posterior capsule. The rotator interval provides the main restraint against inferior instability. (The rotator interval consists of the superior glenohumeral ligament, the rotator interval capsule, the coracohumeral ligament, and the IGHL complex). One study we assessed found that subjects with MDI had significantly greater dimensions at the rotator cuff interval and inferior and posterior-inferior portions of the capsule. Additionally, inferior instability (or excessive inferior glide) was a common findings among patients with MDI. As with any other joint, the approximation of various structures can lead to injury of multiple tissue types with an injury (chronic or acute). The axillary nerve, for example, is at risk for injury with instability (the patient may present with abduction weakness). With MDI specifically, patients often present with rotator cuff tendinopathy, subacromial busitis, or secondary impingement syndrome due to the chronic nature of the pathology.

Diagnosis It is important to know the actual definition of Multiple Directional Instability in order to correctly identify individuals suffering from the disorder. There is some inconsistency in the medical field about how to accurately label these individuals. One common set of criteria include: symptomatic excessive translation of the humeral head with respect to the glenoid in more than one direction (Andrews, Reinold, & Wilk, 2009). When an individual suspect of dislocation is identified, often some form of imaging is requested by medical personnel. The initial technique is an x-ray in all common 3 views: anteroposterior, scapular, and axillary (this often doesn't reveal much in patients with MDI). Should some form of bone loss be suspected, a CT is performed to build a 3D image of the shoulder. In order to identify any soft tissue lesions, a MRI is necessary. If performed in the acute stage, a contrast may not be necessary to differentiate the tissues, but a MR arthrogram is the gold standard for viewing lesions in the shoulder related to instability. To further view a specific part of the shoulder's capsular structure, sometimes the imaging is performed in stressed positions: abducted and ER for anterior and flexed/horizontally adducted/MR for posterior. Occasionally, when nerve damage is suspected, some medical professionals prefer to perform a nerve conduction velocity test (and sometimes an MRI) to establish a baseline for nerve function and observe the progression of its healing. Imaging can also be useful in identify individuals with recurrent instability. The normal shape of the glenoid is an inverted comma. With recurrent instability, the glenoid appears like an inverted pear due to osseous destruction. It is important to identify recurrent dislocators, due to the increased incidence of additional pathologies to the shoulder (rotator cuff tears, Bankart lesions, capsular laxity, etc.). As physical therapists, we are unable to order any imaging in most settings. We have to rely on physical exam measures to determine which patients are showing signs of MDI. Patients with MDI will often present with decreased strength and proprioception, especially in the external rotators, scapular retractors, and scapular depressors. Testing ROM can give varied results, depending on the stage of the injury. In the acute stage, patients often have pain or a sense of apprehension that limit end range movement. In the chronic stage, patient may exhibit excessive ROM. As reported earlier, patients with MDI often exhibit increased instability in one specific direction compared to others; therefore, the tests for directional instability may be utilized for these individuals. To identify anterior instability and posterior instability, the examine uses the anterior and posterior instability tests respectively. To assess for inferior instability, the examiner should perform the sulcus sign. Some additional tests utilized include: Clunk test and the Load and Shift Test. Additionally, tests that identify labral pathology can be useful in determining the extent of the injury.  Conservative Treatment: Physical therapy is the first treatment course for patients with MDI. The patient should limit activities that reproduce pain or apprehension, during rehab to allow the tissues to heal. Additonally, the patient should practice proper posture, due to the stressed placed on parts of the capsule with poor posture. Conservative treatment has been shown to be effective in those suffering from MDI due to impaired muscular control or poor control and strength of the rotator cuff and scapulothoracic muscles. Patients with MDI due to bone or labral deformities have not been shown to have good outcomes with conservative treatment. Because shoulder weakness was found in 75% of MDI patients, upper extremity weight-bearing activities have been thought to play an important role in the management of MDI. In addition, rotator cuff, scapular stabilizer, and deltoid strengthening is a necessary component of the rehab program (focus on scapular stabilizers first to establish a stable base). After addressing the scapular stabilizers, the clinician should focus on strengthening the rotator cuff muscles in order to better centralize the humeral head during dynamic activities. Some clinicians prefer initiating rehab with isometric strengthening exercises or isotonic exercises in a limited range in order to allow time for the tissues to heal. Burkhead found that 80% of patients with MDI showed improvements with rotator cuff strengthening exercises. The exercises should be initiated in the scapular plane, as it is the most stable position. This position places the rotator cuff and deltoid in an optimal length-tension relationship and decreases stress placed on the anterior and posterior capsule. Exercises can be progressed to less stable positions, out of the scapular plane. Towards the end of rehabilitation, additional shoulder muscles can be addressed to further develop supporting musculature (i.e. triceps, biceps, etc.). To address the proprioception deficits, rhythmic stabilization drills can improve function of the mechanoreceptors and neuromuscular control in the shoulder by facilitating co-contraction of the shoulder musculature. Eventually, exercises should be attempted in positions of instability to decrease the muscular reflex that occurs in order to lower the likelihood of recurrent instability. Active repositioning tasks, PNF techniques, weight-bearing and plyometric exercises are also used to treat these impairments. The push-up plus, already known to strengthen the serratus anterior, has been shown to activate the subscapularis - an essential component of the rotator cuff force couple. The clinician should always remember to progress exercises in various ways: speed, intensity, frequency, etc. Stretching and PROM should not be utilized in the MDI patient due to the already excessive ROM present in the shoulder. Glenohumeral mobilizations grade III-IV should be avoided as well due to the desire to decrease capsular stress (grades I-II are permitted for pain treatment). It should be noted that conservative treatment may not be advised for all populations. According to Brotzman & Wilk, individuals < 30 years of age who experience a dislocation have a 70% chance of being recurrent dislocators. One study found that those who sought conservative treatment had a 47% recurrent dislocation rate, while those who sought surgical stabilization had a 15% recurrent dislocation rate. Therefore, patients over 30 years of age who experience a dislocation should seek conservative therapy, while patients under 30 years of age should seek surgical treatment. Always be certain of true dislocation. Often, children may present with increased apprehension for instability testing even without dislocation. Surgical Treatment If symptoms persist following a 6-12 month bout of conservative therapy, surgical treatment may be advised for the patient with MDI. Due to the overall capsular laxity, the surgical technique for unidirectional instability is not successful for patients with MDI. Capsular volume must be addressed. According to Dr. Andrews, the gold standard is the open inferior capsular shift. This technique decreases capsular volume by equilibrating capsular tension on all sides and balancing the humeral head. The approach can be anterior or posterior and is usually decided by the direction of greater instability. Those who seek surgical treatment to address instability may have an increased risk of recurrent instability of the direction opposite the approach of the procedure. The capsule can also be addressed arthroscopically (arthroscopic suture capsulorrhaphy). The advantage to the arthroscopic method is that the surgeon can identify concomitant pathologies (labral injury, rotator cuff tear, etc.) and treat them simultaneously. Thermal capsulorrhaphy is a technique that involves administering heat to the capsule with the hope of focusing on type I collagen. It breaks the cross-links and denatures the proteins, leading to a randomized state of collagen - decreasing capsular volume. This method, however, has been shown to have a high failure rate recently and is rarely used today. References:

Andrews, James, Michael Reinold, Kevin Wilk. The Athlete's Shoulder. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier, 2009. 229-236, 556-559. Print. Brotzman, S., & Wilk, K. Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2003. 197-198. Print. Dalton SE, Snyder SJ. "Glenohumeral Instability." Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1989 Dec;3(3):511-34. Web. 10/21/12. Gyftopoulos S, Bencardino J, Palmer WE. "MR Imaging of the Shoulder: First Dislocation versus Chronic Instability." Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2012 Sep;16(4):286-95. Web. 10/21/12. Illyés A, Kiss J, Kiss RM. "Electromyographic analysis during pull, forward punch, elevation and overhead throw after conservative treatment or capsular shift at patient with multidirectional shoulder joint instability." J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2009 Dec;19(6):e438-47. Web. 10/22/12. Kiss, Rita. "Electromyographic analysis during pull, forward punch, elevation and overhead throw after conservative treatment or capsular shift at patient with multidirectional shoulder joint instability." Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 2009. Web. 22 Oct. 2012 Lee, Hui Jen. "Multidirectional Instability of the shoulder: rotator interval dimension and capsular laxity evaluation using MR arthrography." Skeletal Radiology. 2012. Web. 21 Oct. 2012 Ogston, Jena. "Differences in 3-Dimensional shoulder kinematics between Persons with Multidirectional Instability and Asymptomatic Controls." American Journal of Sports Medicine. 35.8 (2007): n. page. Web. 21 Oct. 2012. Swanik KA, Huxel Bliven K, Swanik CB. "Rotator-cuff muscle-recruitment strategies during shoulder rehabilitation exercises." J Sport Rehabil. 2011 Nov;20(4):471-86. Web. 10/22/12. Yamaguchi, Ken. "Management of Multidirectional Instability." Clinics in Sports Medicine. 14.4 (1995). Web. 21 Oct. 2012.  In this article, Dr. Thacker discusses the need for physical therapists to start thinking differently about pain. We are so focused on the muscles, ligaments, and mechanical structures as the source of a client's symptoms that we often neglect how interconnected the human body is. Specifically, Dr. Thacker discusses the relationship between the nervous system and the immune system. Everyone has structures called cytokines that are located in the CNS and PNS. When tissues become injured and an inflammatory response results, these cytokines are released, activating the nociceptive system. Additionally, we must consider the impact of pain on the brain. Evidence has shown that there is a cortical reorganization in patients with low back pain. When a larger portion of the brain is focused on pain, sensation and motor control are altered. Understanding this paradigm will allow physical therapists to better identify their patient's complaints and plan interventions accordingly!  Similar to the Core Muscle Activation article we posted earlier, this research report demonstrates which exercises elicit the best muscle activation during therapeutic exercises. It also has good visual demonstrations of each exercise. A few highlights: -Sidelying Hip Abduction elicited the greatest Gluteus Medius activation, followed by Single Limb Squat and Lateral Band Walking. -Single Limb Squat and Single Limb deadlift promoted the greatest Gluteus Maximus Activation. -Notice the relatively low Glutues Medius Activation the Clamshell Exercise at 30 degrees and 60 degrees Hip Flexion despite being one of the most used Gluteus Medius strengthening exercises we have seen in the clinic. Looking at the graphs in the article, you can also find several other exercises that are much more functional than the clamshell. Keep in mind how you would progress each of these ex Anatomy Review:

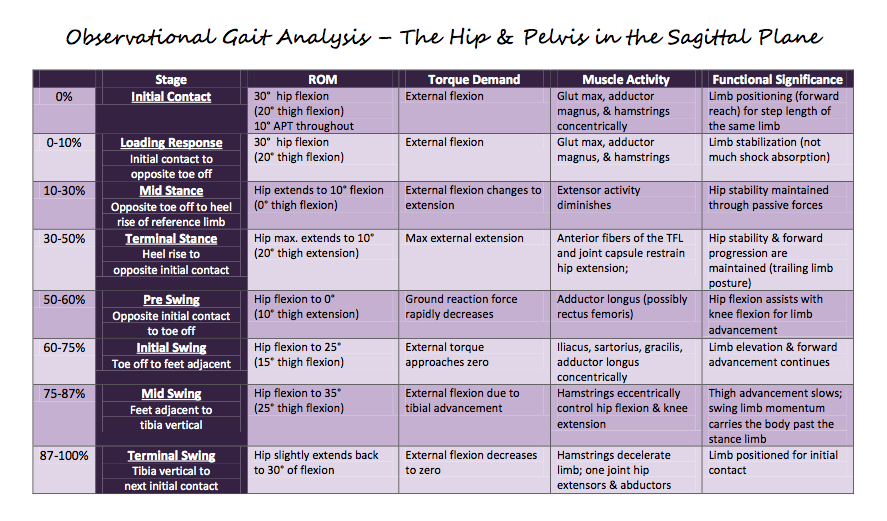

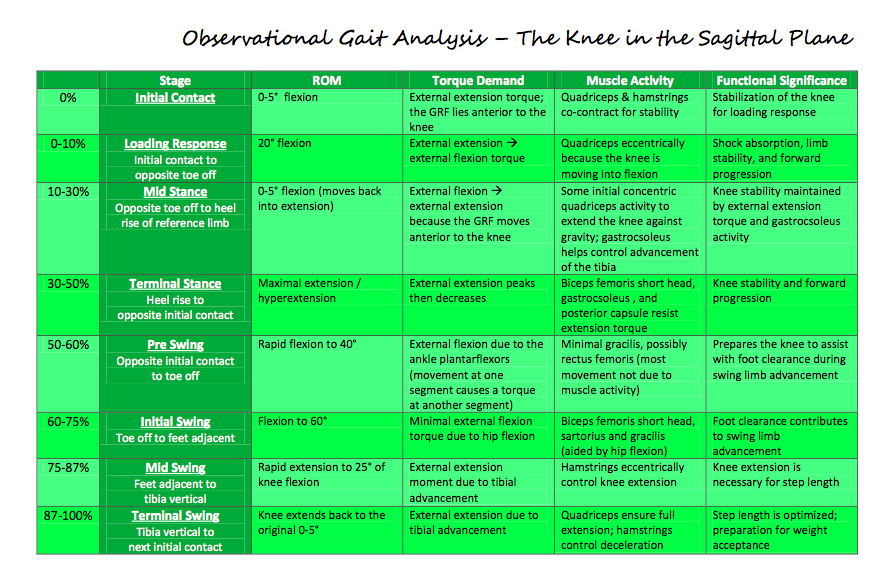

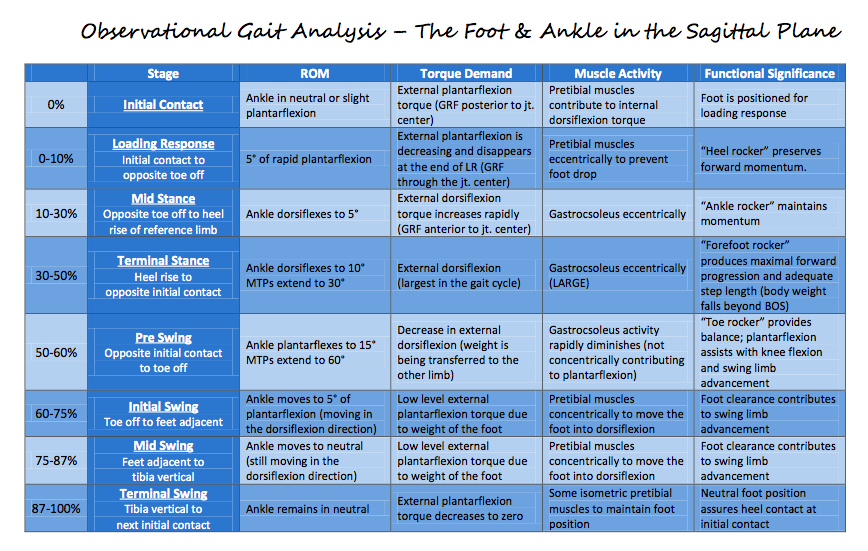

Because we all strive to be movement analysis specialists, a little gait mechanics review never hurts. Each graph breaks down the ROM requirements, muscle, torque demand, and functional significance as described by Rancho Los Amigos. All graphs courtesy of Saint Louis University student, class '12.

It has been estimated that Plantar Fasciitis occurs in approximately 2 million people and can account for between 8% and 15% of all foot pain complaints. While the term "-itis" is often associated with inflammation, there is growing evidence that there might not be an inflammatory state, but rather a degenerative process occurring in the plantar fascia. Because of this growing belief, authors are saying a more appropriate term would be "plantar fasciopathy" or "plantar heel pain." Plantar heel pain is best described as a sharp pain in the patient's rear foot that is worse in the morning (usually the first step out of bed) and at the beginning of a weight bearing activities. The pain typically lessens with continued activity, but often increases toward the end of the day. Individuals most susceptible to developing heel pain are middle-aged women, obese individuals, athletes, and runners. Clinically, you will see excessive pronation and a depressed longitudinal arch in many of these clients. Some extrinsic factors contributing to the pathology include training surfaces, shoe wear, and poor training methods. Understanding the anatomy makes it clear why this population is at an increased risk. The plantar fascia runs from the medial tuberosity of the calcaneus and inserts into the metatarsophalangeal joints, the proximal phalanges, and the flexor tendon sheaths. The fascia is responsible for supporting the longitudinal arch of the foot and assisting in dynamic shock absorption. The attachment of the plantar fascia to the medial calcaneal tuberosity explains why patients often experience pain upon palpation of that area. Diagnosis of plantar fasciopathy is often made on a clinical basis. Due to degenerative changes and tendon thickening, the diagnosis may be made with an ultrasound as well. Current treatment methods include rest, modalities, stretching, strengthening, manual therapy, splinting, orthotics, surgery, and more. New research is constantly being published due to the high incidence of the injury. This review will take an in depth look at several of the available treatment techniques for plantar fasciopathy. Many of the studies we looked at included strengthening and stretching in the treatment plans along with some other intervention. Improvement was often shown in both groups, but we were unable to find any studies that specifically looked at one type of strengthening exercise compared to another. Some of the most common barefoot exercises seen in the clinic include towel scrunching and picking up marbles. Due to the biomechanical theory of the plantar fascia aiding in the support of the medial arch, it would seem logical to include strengthening of the posterior tibialis in rehabilitation. The posterior tibialis is the prime muscle for raising the medial longitudinal arch and can take stress off the plantar fascia. As noted in our previous posts, the exercise to most effectively activate the posterior tibialis is resisted forefoot adduction.

Another study we reviewed compared a new calcaneal taping technique versus a sham taping group, a stretching group, and a no treatment group. The calcaneal taping technique inverted the heel to raise the medial longitudinal arch. A first piece of tape pulled the calcaneus medially. Pieces 2 and 3 followed the same pattern, overlapping 1/3 of each prior piece of tape. Piece 4 wrapped around the heel lateral to medial, supporting the arch and anchoring pieces 1-3. This 4 piece technique was considered quick and cost effective. This calcaneal taping intervention resulted in significantly greater reductions in pain compared to the sham taping, stretching, and no treatment groups. Additionally, a study comparing Medial Arch Support to Low-Dye Taping found that both groups had improvements in pain, but the Medial Arch Support had significantly greater improvements. These interventions should be considered for short-term relief, so that the patient can be pain-free for more intense therapy or activities. A third intervention we reviewed assessed the effects of low level laser therapy in the treatment of plantar fasciitis. Laser treatments were given 3 times per week for 4 weeks with a 30mW . 83 um continuous-wave IR diode laser. The goal of the laser therapy was to alter cellular metabolism, protein synthesis, and create an immune response. The conclusions of randomized controlled evaluation found that low level laser therapy was not beneficial in the treatment of plantar heel pain. A study we looked at compared the effects of stretching and orthotics vs. e-stim, stretching, and orthotics. Both groups improved, but there was not difference between the two groups, so e-stim appears to have no additional benefit. With the recent boom in barefoot running, there has been a movement to begin incorporating barefoot or minimalist exercises/training into rehabilitation of plantar fasciitis. The theory involves placing increased forces on the intrinsic muscles of the foot, so that they can be retrained to support the arch and take stress off the plantar fascia. A study we looked at how the addition of Nike Free 5.0 shoes could affect the patients' complaints. The Nike Free 5.0 shoes offer a flexible midsole that somewhat mimics barefoot training. In the study, two groups were assigned an exercise protocol that involved balance training, stretching and strengthening exercises. One group wore conventional shoes, while the other wore the Nike Free 5.0 shoes. At the end of the study, both groups had a significant decrease in pain, the Nike Free 5.0 shoes more so. Due to the poor design, the results of this study must be looked at closely. At 24 participants, it was a small sample size and there may have been a psychological effect, since the Nike group received new shoes, while the conventional group used old shoes. Along with other factors, it is not clear if minimalist shoes can enhance rehabilitation for individuals with plantar fasciitis. It would be interesting to see the effect of more minimalist-type shoes (New Balance Minimus, Vibram Five Finger, etc.) could have on therapy in a properly done study.

One of the more common interventions that is performed is stretching. A study we looked at compared the results of the standard achilles tendon stretch to a sitting plantar fascia stretch. For the plantar fascia stretch, the patient would cross his/her legs and place the affected foot on the opposite knee. The patient then grasps the toes (especially the big toe) and maximally dorsiflexes them until a stretch is felt in the foot. In the study, the patients would perform their stretch first thing in the morning and before getting up after sitting for awhile. The study found both interventions to be successful, but the plantar fascia specific stretch more so. It should be noted that the study had no true control to rule out the patients' improvements due to natural healing processes. Dry needling is still a limited treatment technique for physical therapists; however, patients can have access to acupuncture on a wider basis. One article compared two groups to see the effect of acupuncture on plantar fasciitis. Both groups received standard treatments, such as icing, stretching, intrinsic foot strengthening, and NSAIDs. One group received acupuncture, additionally. Both groups found improvements in pain. There was no difference between the two groups after 4 weeks, but the acupuncture group was slightly better after 8 weeks. A treatment technique that is gaining popularity involves Instrument Assisted Soft Tissue Mobilization (IASTM). There are many products out there that fall under the category of IASTM: Graston Technique, ASTYM, Edge Tool, etc. The theory is generally the same behind them in that, through use of the tools, a healing inflammatory phase can be initiated by stimulating blood flow, nutrients, and fibroblasts to the area. Through proliferation of the fibroblasts, healing and formation of collagen can begin. The soft tissue mobilization can additionally aide in reorganization of the collagen fibers to proper orientation. This study in particular was a preliminary look at Graston Technique, discussing the theory, protocol, initial evidence, and some case studies. As plantar fasciitis is a soft tissue pathology, IASTM could have useful implications for patients with this disorder. When further research is performed on the subject, it may be found that IASTM has a very important place in treating these patients. References:

Abd El Salam MS, Abd Elhafz YN. "Low-dye taping versus medial arch support in managing pain and pain-related disability in patients with plantar fasciitis." Foot Ankle Spec. 2011 Apr;4(2):86-91. Web. 10/13/12. Bassford, Jeffrey. "A Randomized Controlled Evaluation of Low Level Laser Therapy: Plantar Fasciitis." Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 79. (1998): n. page. Web. 8 Oct. 2012. Beyzadeoğlu T, Gökçe A, Bekler H. "[The effectiveness of dorsiflexion night splint added to conservative treatment for plantar fasciitis]." Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2007;41(3):220-4. Web. 10/13/12. Digiovanni BF, Nawoczenski DA, Malay DP, Graci PA, Williams TT, Wilding GE, Baumhauer JF. "Plantar fascia-specific stretching exercise improves outcomes in patients with chronic plantar fasciitis. A prospective clinical trial with two-year follow-up." J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006 Aug;88(8):1775-81. Web. 10/12/12. Hammer, WI. "The effect of mechanical load on degenerated soft tissue." J body Mov Ther. 12.3 (2008): 246-256. Web. 8 Oct. 2012. Hyland, Matthew. "Randomized Control Trial of Calcaneal Taping, Sham Taping, and Plantar Fascia Stretching for the Short-term Management of Plantar Heel Pain." Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 36.6 (2006): n. page. Web. 8 Oct. 2012. Karagounis P, Tsironi M, Prionas G, Tsiganos G, Baltopoulos P. "Treatment of plantar fasciitis in recreational athletes: two different therapeutic protocols." Foot Ankle Spec. 2011 Aug;4(4):226-34. Web. 10/13/12. Lee SY, McKeon P, Hertel J. "Does the use of orthoses improve self-reported pain and function measures in patients with plantar fasciitis? A meta-analysis." Phys Ther Sport. 2009 Feb;10(1):12-8. Web. 10/10/2012. Renan-Ording, Romulo. "Effectiveness of Myofascial Trigger Point Manual Therapy Combined with a Self-stretching Protocol for the Management of Plantar Heel Pain: A Randomized Control Trial." Journal of Orthopedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 41.2 (2011): 43-51. Web. 8 Oct. 2012. Ryan, M, S Fraser, K McDonald, and J Taunton. "Examining the degree of pain reduction using a multielement exercise model with a conventional training shoe versus an ultraflexible training shoe for treating plantar fasciitis." Phys Sportsmed. 37.4 (2009): 67-84. Web. 10 Oct. 2012. Stratton M, McPoil TG, Cornwall MW, Patrick K. "Use of low-frequency electrical stimulation for the treatment of plantar fasciitis." J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2009 Nov-Dec;99(6):481-8. Web. 10/13/12.  Tendinosis, Tendonitis, Tendinopathy... what is the correct term? This article written by Mark Reinking critically analyzes the tendon structure and it's response to exercise. Abstract: Overuse related tendon pain is a significant problem in sport and can interfere with and, in some instances, end an athletic career. This article includes a consideration of the biology of tendon pain including a review of tendon anatomy and histopathology, risk factors for tendon pain, semantics of tendon pathology, and the pathogenesis of tendon pain. Evidence is presented to guide the physical therapist in clinical decision-making regarding the examination of and intervention strategies for athletes with tendon pain. Highlights: -Human tendons demonstrate minimal hysteresis. Most stored elastic energy is released when the tensile load is removed. -The degradation of collagen that happens after exercise is greater than the increase of collagen synthesis that occurs. -There is an up-regulation of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) in pathological tendons. VEGF factor stimulates neovascularization. This process decreases collagen strength and creates micro-tears. -Some new evidence supports eccentric strength training in the management of non-insertional achilles tendinopathy, patellar tendon pain, supraspinatus tendinopathy, wrist extensor tendinopathy, and posterior tibial tendinopathy (check out some of our previous posts on the topic!). |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed