- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

As this was my student's first initial evaluation on this clinical (and first ortho one in months), I can understand being a bit nervous and focusing in on the knee. The patient had complaints of vague thigh pain and the need to do a wider examination became even more apparent. I encouraged the student to perform a lumbar spine examination and slump test. Both back and the thigh pain were recreated, suggesting lumbar involvement to the current impairment level. While I typically prefer using the SFMA for evaluations, I typically do not do so with post-surgical patients. That being said, I do still have a system that I run through in assessing surgical patients. For example, in any lower extremity or back surgery, I assess lumbar/hip/knee/ankle mobility and strength, SIJ pain provocation tests, hip scour/FABER/POSH tests, neural tensioning, and segmental mobility. Based on the surgery, sometimes a modification is needed, but I still like to assess each area for potential contribution to the patient's pain and limitations. The benefit of having some form of a systematic examination results in lowering the chances of missing true causes and sources of the pain. Both are listed because the source of pain is not always the reason pain occurred in the first place.

While this was a difficult patient to evaluate, I am happy that my student was able to experience it so early in the rotation. It served a perfect example as to why we need to be thorough with our examinations, no matter the referral. Since then, she has done an outstanding job of taking a more global approach with each assessment. Physical therapists often go years before recognizing the need for development of a system. While this post might appear somewhat redundant to the previous posts we have had on the topic, the value of becoming more efficient clinicians can not be over-emphasized. -Chris

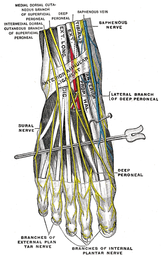

0 Comments

Thoracic Manipulations have received a good amount of attention in the literature in recent years. Whether you are treating a shoulder, cervical spine, or lumbar spine, the thoracic manipulation has been shown to have positive effects on all of these regions. The exact science as to why a manipulation is beneficial is not yet understood, but the most recent evidence suggests that it is multi-factorial. Some proposed effects include: 1) Mechanical- breaking up intra-articular lesions 2) Neurological- stimulates mechanoreceptors & "resets" nocioceptive pathways 3) Hydraulic- change the viscosity of synovial fluid 4) Relaxation- decrease in muscle tone & restore normal blood flow 5) Psychological- both laying hands on the patient & hearing a "pop" are strong influences Below is a quick video on how to perform the the Thoracic Manipulation in Supine. With the supine technique you are flexing the thoracic spine, which makes it a facet gapping technique. The thoracic manipulation can also be performed in prone and seated positions, which can be utilized based on the patient's restriction and position of comfort. As with all manual therapy, it is important to reinforce the treatment with corrective exercises to maintain the positive effects gained from the manual technique.  Following a lateral ankle injury, a patient often presents with swelling, pain, decreased ROM, an acute joint dysfunction, and decreased proprioception in the foot and ankle. Depending on the severity of the injury, these symptoms usually begin to improve within a matter of weeks. However, occasionally symptoms persists despite doing all the proper things during your treatment sessions. Most commonly, if a lateral ankle injury occurs the Anterior Talofibular Ligament (ATFL) will be stressed and injured. The mechanism of injury stressing the ligament typically includes adduction and traction of the talus on a plantarflexed and inverted foot. What many individuals fail to consider is the close interaction between the Intermediate Dorsal Cutaneous Nerve (a branch of the superficial peroneal nerve) and ATFL. The Intermediate Dorsal Cutaneous Nerve courses just superior to the ATFL and can also undergo a significant amount of stress during a lateral ankle inversion injury. The nerve is purely sensory and provides sensation to the dorsal aspect of the foot. When the nerve has been irritated, common clinical findings include pain, paresthesia, and a + Tinel's Sign. To check for neural tension in the superficial peroneal nerve (you cannot solely tease out the Intermediate Dorsal Cutaneous Nerve), have the patient lie in supine. Bring the affected foot and ankle into plantar flexion and inversion. Next, perform a straight leg raise on the affected limb while maintaining the foot in PF and Inversion. If pain increases, this is positive neural tension. It is very important to perform the straight leg raise because if you only perform PF and Inversion, pain could be coming from either the ligamentous injury or neural tension. You must further tension the nerve proximally. One should be quick to point out that neural tension may be present, but it is not always the cause of a person's symptoms. In order for the neural tension to be considered relevant adverse neutral tension it must fulfill 3 criteria: 1) Does the test reproduce their pain? 2) Is there a side to side difference? 3) Does the pain change by moving a distant component? Assessing neural tension is one quality that differentiates the novice clinician from an expert. Next time you see a lateral ankle injury, consider the interaction between the Anterior Talofibular Ligament and the Superficial Peroneal Nerve.

With the common perception that the UT is often short (especially with patient reports of the muscle feeling "tight" when put on stretch - of course), it is not surprising that stretching is frequently prescribed for the muscle in patients with neck and/or shoulder pain. That's not to say it is never warranted. If the muscle length is truly assessed and found to be adaptively shortened (and non-painful), of course we want to stretch the muscle. However, we must be certain that the muscle is indeed shortened first. If the UT is truly shortened, you will find the entire shoulder heightened compared to normal, meaning both the superior angle and acromion of the scapula. Often patients are seen with an elevated superior angle but depressed acromion, suggesting a downwardly rotated scapula - components of an overactive/shortened levator scapula. An exercise commonly performed at the gym involved shoulder shrugs holding weights with the idea that the individual is strengthening the UT. However, in this position, the scapula is rotated downward and results in strengthening/reinforcing the levator scapula muscle (Sahrmann, 2002). An overactive UT is also frequently accused as the culprit in shoulder impingement. However, remember that about 1/3 of shoulder elevation is due to upward rotation of the scapula, an action of the UT. Frequently, the patient will display elevation of the scapula when trying to flex or abduct the humerus. Attention should be paid to whether or not the scapula is in upward or downward rotation with that elevation. If it appears to be downward rotation, it is essential that the UT undergoes retraining. In order to focus on the UT, the shoulders should be placed in at least 90 degrees of elevation in order to place the scapula in upward rotation and allow the shrugging aspect of the motion to come from the UT, not just the levator scapula. An additional point that should be considered is the impact on the cervical spine. Sahrmann places a strong emphasis on relative stiffness and hypermobility vs. hypomobility in her teachings. As previously discussed, the UT attaches to the cervical spine and, in doing so, can be responsible for pain at the attachment site. There are at least two possible reasons for cervical pain resulting from UT impairment. One, the UT is overactive and stronger compared to the cervical intrinsic muscles. When the muscle contracts such as during upper extremity elevation, cervical extension or rotation is frequently seen (Sahrmann, 2002). You can even feel the individual cervical vertebrae rotating during shoulder flexion/abduction. This hypermobility (a precursor to hypomobility) provides the excess stress that can lead to degeneration and, in the long run, hypomobility. In this case, the UT needs to be retrained with an emphasis placed on maintaining cervical stability and neutral cervical positioning. Two, the UT is insufficient and lengthened, resulting in a pull on the proximal attachment (cervical vertebrae) due to the weight of the scapula and upper extremity, especially during movements. These patients, too, will report that "stretching feels good." Just as the previous example, however, we must strengthen the UT in these patients, with proper positioning as explained earlier. The purpose of this post was to make us all more aware and pay specific attention to the scapulohumeral positioning both statically and dynamically in order to determine the true impairment that lies with the UT, or if there even is one at all. A starting point we like to use is assessing the medial side of the scapula at rest to determine if the resting position is upward or downward rotation. That should be followed up with a comparison of the superior angle of the scapula to the acromion as well to aid in confirmation. This positioning should then be tracked during flexion/abduction of the humerus. This is just one muscle's impact on the upper quarter, but as you can tell, it is a significant one. For more information on the topic, it is recommended you review the references listed below. References:

Kendall FP, McCreary EK, Provance PG, Rodgers MM, & Romani WA. Muscles Testing and Function with Posture and Pain. 5th edition. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005. 326. Print. Sahrmann, SA. Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 2002. 206-208. Print. |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed