- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

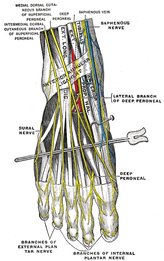

I recently evaluated a patient with lateral foot/ankle pain that another PT had recently treated. The injury was previously diagnosed as a lateral ankle sprain, even though the injury had occurred over a year ago. As some of you may be aware, I wrote a similar post several months ago regarding a "chronic calf strain." In both cases, the length of time since injury should have been a major clue. Sprains and strains should recover within several weeks. Injuries and pain that persist are significant sign of pain containing a neural component. Some other subjective and objective exam findings that can help you clue in on this include: pain of a vague presentation, reproduction of pain with neural tension, and the presence of pain proximally. The patient I examined had all of these factors. The pain was located all over the lateral foot and ankle area (not a specific spot like most musculoskeletal compliants). The patient had some mild back pain and a job that requires prolonged desk work. Finally, the patient's pain was reproduced with a SLR biasing the common peroneal nerve. It should be pretty apparent that the patient wasn't simply suffering from an ankle sprain from a year ago, based solely off the subjective. Time frame from injury can be a good clue. I should point out that the patient did not report back pain, even after initial questioning. Typically, I have to repeatedly ask patients about any back pain or history of back pain. Many people consider back pain a part of normal aging and not worth reporting. This is where having a thorough and systematic evaluation can come into play. I typically advocate the Selective Functional Movement Assessment (SFMA) as it forces you to look at the whole body in examination. Significantly dysfunctional and/or painful spinal mobility can be identified here and play a role in your treatment decision. Even if the patient had denied back pain and none was found in examination, the presence of spinal mobility deficits is likely pertinent and should be addressed. -Chris Like this post? For more advance information, join the Insider Access Page!, Also, check out similar previous posts below.

0 Comments

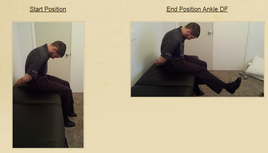

A few months back I wrote a differential diagnosis POST discussing the intermediate dorsal cutaneous nerve vs. ATFL sprain. Last week I was working with a gentleman 4 weeks post inversion ankle sprain. The patient's subjective report: "My strength and ROM have significantly improved. I have minimal pain except a burning sensation on the top of my outer three toes." The burning sensation was increased with palpation and single leg weight bearing. A common peroneal nerve stress test (SLUMP test while biasing the foot and ankle in PF/IN) revealed reproduction of the patient's symptoms. The symptoms met the 3 criteria for positive neural tension: 1. side to side difference 2. reproduction of the patient's symptoms 3. changes with a distant component. How do you treat peripheral nerve tension? The keys to treating nerve tension are: 1. Mobilization/manipulation of the joints which the nerve passes 2. Nerve gliding/sliding exercises 3. Soft tissue mobilization 4. Light endurance exercises. 5. Education My daily treatment to give you an idea how to treat common peroneal nerve tension: First, I manipulated the mid-thoracic spine to mobilize the sympathetic nervous system. Then I reassessed the asterisk sign. Symptoms improved (SLUMP test with PF/IN bias), but were not abolished. Next, I manipulated L4-L5 to further mobilize the common peroneal nerve. Reassessing the asterisk sign completely relieved the patient's symptoms. Third, I addressed talocrural joint mobility since the joint was hypomobilie and affecting the ability to heel to toe strike Fourth, I performed endurance and corrective exercises, I had the patient perform 15 minutes on the stationary bike, followed by two ankle mobility exercises, calf raises, and gait training on the treadmill promoting heel to toe progression and toe off. Would you have done anything differently? Jim Like this post? Check out others from TSPT or our INSIDER ACCESS PAGE!

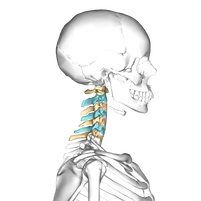

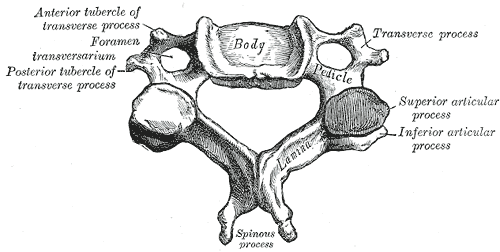

Assessing segmental mobility in those with nonspecific neck pain vs. asymptomatic individuals4/21/2015  A recent study was published in JOSPT that examined stiffness in the cervical spine in those with nonspecific neck pain and asymptomatic individuals. The results revealed a difference in stiffness between the two groups. This should come as little surprise to those with manual therapy background, but the methods may raise some concern. For example, the age range was quite large (18-55), which may allow for significant differences in normal "stiffness" based on age-related degeneration. Interestingly, a standardized device was used for measuring how much force was required to move a segment. While it helps to consistently apply the same force in assessment (reducing inter- and intra-rater reliability), the validity of what should constitute stiffness isn't as thoroughly established. However, the presence of a significant difference in stiffness still warrants inclusion of these results in our clinical reasoning. Why there is a difference in stiffness isn't as clear. One theory is that with the perceived "pain," there is an increased level of tone in the surrounding muscles, limiting the motion at the spinal segments. What should be noted, however, is that there was no correlation between the magnitude of stiffness and the level of pain. This may be explained by modern pain science theory, where amount of dysfunction doesn't typically match the perceived amount of pain. What is the impact of this study to us? It may be unlikely that we, as therapists, can manually detect the presence of stiffness in the cervical segments. That doesn't mean the findings are insignificant. The fact that there is a difference between the groups suggest there is potential for future assessment. Also, it appears to be another sign to enhance some previous research regarding the benefit of manual therapy combined with exercise improving mechanical neck pain. With patients with nonspecific neck pain demonstrating stiffness in the cervical spine, we should consider using a method to improve mobility restrictions in our plan of care. Identifying restrictions can be difficult, but using a standardized examination format can enhance our ability to detect overall mobility restrictions. Reference: Ingram LA, Snodgraass SJ & Rivett DA. (2015). Comparison of cervical spine stiffness in individuals with chronic nonspecific neck pain and asymptomatic individuals. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2015 Mar;45(3):162-9. Like this post? Fore more advanced information, join the Insider Access Page! Also, check out similar previous posts below.

Last week I was evaluating a 50 year old male status post peroneal tendon debridement and repair. The patient had spent 6 weeks in a cast and was seeing me 1-week after cast removal. The two pictures below show how the foot and ankle presented upon initial evaluation. My initial differential diagnosis included: 1. normal foot, 2. infection, 3. CRPS. Further inspection revealed signs of skin trophic changes, swelling, pain, hypersensitivity to light touch, nail bed changes, coolness of the lower limb and difficulty initiating movement. The patient denied constitutional signs and symptoms- fever, chills, headaches, night sweats. The incision appeared to be healing normally. He had limitations in ankle ROM and strength. Interestingly, the patient had a positive SLUMP test with intermediate dorsal cutaneous nerve bias (branch of the superficial peroneal). The patient's symptoms had centrally sensitized! After being in a cast for 6 weeks with high levels of pain, the CNS forgot how to interpret normal sensation and movement of the foot. On the initial evaluation, I performed a thoracic manipulation to stimulate the autonomic nervous system as well as performed common peroneal nerve glides. Additionally I prescribed the ankle alphabet and towel scrunches bilaterally to facilitate bloodflow and movement as well as promoting small amounts of weight bearing. I chose to perform each exercise bilaterally so that the patient would receive neural overflow from the intact side. Additionally, I gave ample education to the patient regarding the nervous system and pain science. Even in surgical cases, remember that the cause of dysfunction may be distant from the site of injury! More pictures and progress updates to come. -Jim Check out our Insider Access page to see specific testing for lower extremity nerves! Like this post? Check out other posts by TSPT.

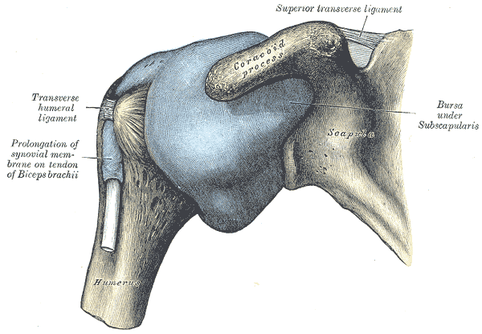

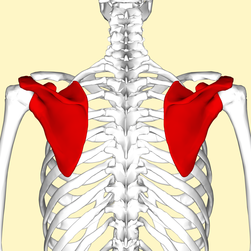

One of the staples of physical therapy and kinesiology foundations includes the convex-concave rules of joint motion. It states that when a convex surface moves on a concave surface, the convex surface rolls one way and glides the opposite direction. If a concave surface moves on a convex surface, the concave surface rolls and glides in the same direction. This can be crucial to understand for both joint mobility assessment and manual treatment. That being said, the convex-concave rules do not always apply to joint kinematics or mobilizations. For example, when reading about the shoulder mechanics in The Athlete's Shoulder, many studies were cited saying, there was a gross movement in the rolling direction typically for the various shoulder movements (I apologize for the lack of specific citation, but I read the book several years ago and do not own it). For example, external rotation exhibited a net posterior translation. That doesn't mean that opposite gliding motion isn't necessary, but that we can't always assume that if a patient has restricted shoulder motion one way, we should mobilize the capsule the opposite way. In Johnson et al's study, shoulder ER mobility improved greater with posterior mobilization of the capsule compared to anterior mobilization. According to convex-concave rules, anterior mobilization should be the choice. Now something to be aware of in the study, is that the patient population was of patients with Frozen Shoulder. It is possible that these patients respond differently to mobilizations and that the above study doesn't always apply. Clinically, what does this mean? We shouldn't always expect that the convex-concave rules will apply. What I recommend is when assessing a joint, look for restrictions and lack of stability in each plane. For example, note in a shoulder if there is increased laxity (or even potential subluxation) in one direction and increased stiffness in another. Mobilize the hypomobile direction if you find one. In a case like adhesive capsulitis, the patient will likely benefit from mobilization in any direction. -Chris Reference: Johnson AJ1, Godges JJ, Zimmerman GJ, Ounanian LL. (2007). The effect of anterior versus posterior glide joint mobilization on external rotation range of motion in patients with shoulder adhesive capsulitis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007 Mar;37(3):88-99. Like this post? For more advanced information, join the Insider Access Page! Also, check out similar previous posts below.

This post was shared from OPTIM Manual Therapy Fellowship Facebook page.

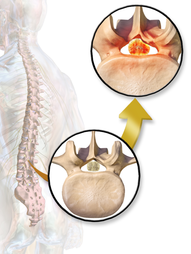

Background information: Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) is a pathological condition involving the spinal canal or nerve root foramen. Symptoms often include back pain, leg pain, and numbness and tingling. If the spinal cord is compressed, more severe symptoms include loss of bowel and bladder function. Conservative management (physical therapy) of LSS is inconsistent and highly varied across the country. Currently, surgery remains a popular treatment option for many of these individuals. New Study: How Our Practice is Changing! Anthony Delitto et al recently published a new article, "Surgery versus Nonsurgical Treatment of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: A RCT." The study followed 169 patients diagnosed with LSS to see if one intervention proved to be superior to the other at 24-month followup. The conclusion was that each intervention (surgical decompression and PT) yielded similar long-term results. What does this mean? The impact of this study is huge for PT practice. Lumbar spinal stenosis is a major cause of low back pain in the United States. We now have evidence demonstrating that physical therapy is equally successful as surgical management. These individuals do not always need surgery! The physical therapy interventions included in the study were largely lumbar flexion exercises (posterior pelvic tilts, supine knee-to-chest exercises, quad rocking) and general conditioning exercises. Conclusion More and more evidence is emerging regarding the long term management of many orthopedic conditions. Unfortunately, a large majority of the public has not and will not see this study for several years. Literature takes years to reach the clinic and even longer to reach the patient. We need to start educating patients on the impact of this study today. Next time you are working with a patient with a pathoanatomical diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis, discuss with them the long term management of the condition and spend time educating them regarding the pathology. Remember the anatomical problem is usually not causing the movement dysfunction. After performing an appropriate differential diagnosis, let the patient know that physical therapy is the best treatment for their low back dysfunction. Please read the entire article to gain more knowledge regarding inclusion criteria, limitations, and statistics that were utilized. -Jim Probably one of the hardest parts of assessing for a patient's directional preference with repeated motions is knowing if a patient is actually responding to the motion positively. It's not that it's difficult for us, as therapists, to know, it's that patients often struggle to properly communicate what they are experiencing. There are several things to look out for when assessing repeated motions. One, is a decrease in pain. Obviously if the pain feels better, we want to continue with the motions. Second, is centralization of symptoms. This one can be somewhat difficult, because a patient may experience symptoms in an area they previously had none. The pain could get worse proximally, but if it improves distally, it is a positive sign. Both an improvement in motion and motion before pain occurs can be positive as well. We are loading the directional preference with repeated motions, which often has a loss of motion to start, so an improvement in mobility is highly desirable. All of these things, if seen, can be positive with either the repeated motion or an asterisk sign (the motion or activity that the patient has pain with). What you want to watch out for is when symptoms stay peripheralized or worse for 5 or more minutes when done. Why this can be difficult, is that we can only observe so much as therapists for these findings. Some of the markers are subjective. You'll likely notice that patients with signs of central sensitization or a fixation on their MRI findings are so convinced that what you are doing won't help (or will make them worse) that they don't even give the assessment/treatment a chance. This is why it is essential to first thoroughly explain how beneficial the treatment can be and what exactly they should be looking for. Some education of the lack of correlation between pain and imaging findings likely is beneficial as well. Finally, don't be afraid to continue with up to 100 or more repetitions when assessing. Likely, 20 repetitions alone may prove insignificant, but over time the 100 may make a significant change and lead to a more confident result. Be sure to educate your patients on what exactly they should be looking for and don't be too quick to give up!

-Chris A recent article was published in the Washington Post discussing the costs of an MRI vs. physical therapy regarding low back pain. Not surprisingly, individuals who were referred directly to physical therapy saved on average $4,793 as opposed to the group requiring an MRI. What are the reasons behind the cheaper costs?

One of the biggest reasons behind the increased costs of an MRI is the patient's fear associated with benign findings. An MRI will detect all 'pathology' of the spine: disc herniations, degenerative disc changes, and more (I use the term 'pathology' lightly because more and more research is confirming that these changes are a natural part of aging). In many instances these findings are not the cause of a patient's pain. As Julie Fritz, PT, PhD points out in the article "most people older than 40 or 50 have it [DDD] to some degree." These previously unknown findings scare patients to seek additional more expensive treatment. Another reason behind the high amount of referrals for MRI is a physician's financial interest. The article states that the average MRI cost $1000-$1500 and many insurance companies will reimburse the expense. Evidence has shown us that an MRI is not an appropriate intervention for low back pain, unless the patient presents with specific signs and symptoms. As Fritz states "there is a place for advanced imaging. It is just not early in the course of care for most patients." What can we do? 1) Educate our patients! MRIs continue to be ordered because public perception is still permitting it. We need to educate our patients that an MRI is likely not the solution to their problem. Educate the patient regarding the aging spine. For example, I tell my older patients that disc degeneration is extremely common and that these changes can be thought of as internal gray hair. They are an inward sign of aging. Additionally, I educate them that benign changes are common in healthy individuals as well. One's acute episode of pain was likely not due to chronic arthritic changes. 2) Educate yourself. A key component of my residency training at the Harris Health System was pain science education. We spent several lecture sessions discussing the relationship between our patient's symptoms and their MRI/X-ray findings. As a profession, we now know more about the brain and it's response to pain than ever before. Make sure you are staying on top of the literature regarding the benefits and risks of imaging. -Jim |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed