- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

|

Overview: The SLUMP test is a highly sensitive test that can elicit positive neural tension in even asymptomatic individuals. The test can be used in conjunction with other neural tension testing (straight leg raise) and is often a great concordant (asterisk) sign to demonstrate within treatment progress. Due to the complexity of this test, consistency is key. To ensure you are performing the SLUMP correctly, you must be systematic. Perform the same order of events with every patient, every time. Proper Start Position: 1) The patient sits upright with their popliteal creases against the back of the plinth. 2) The therapist presses the knees together and releases them to maintain a neutral position of the lower extremities 3) The patient folds their arms behind their low back *These 3 steps are to maximize consistency Performing the Test: 1) Have the patient slowly slouch from their thorax spine (this will also create lumbar flexion) 2) SLOWLY flex the head toward the sternum 3) SLOWLY begin extending the knee* 4) SLOWLY dorsiflex the ankle* 5) Extend the cervical spine (move a distant component) *In steps 2, 3, and 4, I emphasize SLOWLY because the test is intended to pick up adverse neural tension. Many individuals will push past the onset of neural tension and confound the results of the examination. Remember, neural tension is only positive if their is a side to side difference, reproduces their primary complaint of pain, and if symptoms change by moving a distant component. Turn the SLUMP Test into a Treatment: Fortunately, setup and treatment for positive neural tension findings can be very similar. Check out our HEP program page on Slump Sciatic Nerve Glides to improve your intervention selection. Additionally, for more information on neurodynamic testing and treatment check out our guest post from Darrin Staloch. -Jim Heafner PT, DPT, OCS Learn more about the Lumbar Exam!TSPT Lumbar Spine course has over 5 hours of lecture dedicated to lumbar examination, treatment, biomechanics, and more! The course outlines multiple treatment options include Sahrmann, repeated motions, and manipulative therapy. Click below to learn more!

0 Comments

As many of you know, we recently launched a Home Exercise Portion to our website. They consist of many exercises that we prescribe and programs like VHI don't contain. I wanted to highlight one exercise today, the Quad Rock Back, because of all of uses for it. The exercise is a staple of the Shirley Sahrmann philosophy. While it is listed under the "Low Back" section, it is often prescribed for cervical, shoulder, and hip patients as well. We will break down how the exercise can be used for each region. As described in the video, when this exercise is performed for cervical patients, often the head begins to extend or flex while rocking back. This is a result of abnormal movement and compensatory patterns in the cervical spine. For cervical spine patients, we encourage a chin tuck so that no neck movement occurs during the rocking.

There are many reasons why I like to give this exercise to shoulder and hip patients, one being joint compression. We are taught in our manual therapy classes that joint compression can be beneficial for healing; it also can help mobilize the posterior capsule. It also helps mimic the developmental patterns of weight bearing on the upper extremities, and thus is a critical part of rehabilitation. Additionally, the quad rock back exercise can be use to help normalize scapulohumeral movement patterns and avoid any compensatory activity. While performing the exercise, the movement can be completed by actively flexing the hips, instead of pushing away with the UE's. This allows the shoulder to move in a more normal pattern. Similarly, the exercise can help with unwanted hip musculature activity. By reversing the directions (instructing the patient to push with the hands and not actively flex the hips), the patient can decrease abnormal femoral head sliding and thus compete hip flexion less painfully. The exercise can be used both for treating and assessing and low back dysfunctions, and not just because it is one of the more comfortable positions for low back pain. If you take your patient into quadruped and have them rock back, pay attention to the pelvis, hips, and low back. You may note a deviation to one side, suggesting increased muscle activity, stiffness, or movement patterns. Often you will note premature lumbar flexion compared to end-range hip flexion. This is secondary to all the sitting we do throughout the day - our lumbar spine becomes more flexible compared to the hip! By encouraging the patient to maintain a stable lumbar spine while rocking back (this can be done by placing a stick across the low back - if it falls off, we know there has been abnormal movement). This teaches our patients to isolate hip movement from back movement. While I may not subscribe to all of Sahrmann's theories on movement impairment syndromes, especially in the acute phase, I do appreciate the focus she places on changing compensatory patterns with her exercises. Many of these patterns stem from abnormal postures or repetitive tasks that we perform throughout our daily lives. The rehab focuses on resisting any changes in movement that occur as a result. I have found that I get better results with incorporating repeated motions into my treatment, but I continued to use Sahrmann exercises to try and retrain movement afterwords. -Chris  A few weeks back, I wrote a post about assessing for Lumbar Extension Rotation Syndrome (ERS) in low back pain patients. Since then I have received several comments from people wanting information regarding treatment options for this condition. Overview A typical patient presentation includes age >55 years old, chronic low back pain, and may be involved in a rotational sport (golf, tennis, etc). On physical examination, you will observe an exaggerated lumbar lordosis, paraspinal muscle asymmetry, excessive pelvic rotation during gait, and hinging during cardinal plane extension testing. They will often complain of unilateral lumbar pain that increases with extension and is relieved with non-weight bearing lumbar flexion. Generally a patient with ERS hyperextends their low back, which does not allow the gluts to fire properly. Treatment For the purposes of this post, I want to focus on core stability and lumbopelvic disassociation. I find that pure hip strengthening is not appropriate early on because the patient cannot adequately engage their gluteals without lumbar compensation. Since the patient has excessive lumbar lordosis and hinging during functional movements, addressing core stability is essential. Additionally, strengthening and motor control of the hip extensors and external rotators is important once the core has sufficient control. Manual therapy is performed on a patient-to-patient basis depending on individual impairments found during the physical examination. Since the patient is generally hypermobile at the hinging segment, they are hypomobilie cranially or caudally. Thoracic and lumbar mobilizations and manipulations are appropriate for the appropriate patient. Core Stability Assuming the patient has low irritability levels and good body awareness, I will usually begin TherEx by retraining the transversus abdominus (TrA) in supine. After the patient can maintain a neutral low back position, I will incorporate the bent knee fall out exercise using a blood pressure cuff for additional cueing. Many progressions of the blood pressure cuff are appropriate until the patient demonstrates good isolation of the TrA in supine. As the patient progresses, I take them through a progression of exercises in quadruped to ensure the patient can maintain a neutral low back posture in a gravity independent position. The progression includes isolated TrA contraction, TrA hand heel rocks (see below), and removing limbs from the table (alternating shoulder flexion, alternating hip extension, then birddog exercises). When the patient can demonstrate good control in quadruped, I address core control in spinal weight bearing. In standing, I have found using the wall as an external cue helps the patient 'find' their TrA. When appropriate, begin functional training in standing by incorporating mini-squats, lunges, and other upper and lower extremity disassociation exercises. Below is a progression of 3 common exercises I prescribe for ERS from supine to standing.

Please let me know if you have any questions or would like more information regarding treatment options of extension rotation syndrome. -Jim In the video below, Kelly Starrett discusses how sitting throughout the day places the hip joint in a poor position for normal daily movements. In the video he discusses how prolonged sitting places the psoas muscle in a short, contracted position. As an individual attempts to stand from this position, he/she hyper-extends the lumbar spine. Biomechanically, a tight psoas and shortened lumbar paraspinals draw the pelvis into an anterior pelvic tilt and the lumbar vertebrae into extension. Be aware: the chest may appear upright- giving the impression of natural movement,- but a closer look at the L-spine reveals movement beyond the neutral range. The problem with sitting exists beyond the chair as well. Normal standing posture requires little muscular action to maintain an upright position. In the presence of a hip flexor contracture due to prolonged sitting, forces are placed anteriorly across the hip requiring the hip extensors to counteract the force. Increased muscular action and metabolic cost creates the desire to sit, perpetuating the circumstance which initiated the hip flexion contracture (Neumann 2010).

The Student Physical Therapist Advice: Engage the Transversus abdominus (TrA) prior to moving from sitting to standing. The TrA provides a posterior pelvic tilt to counteract the force of the psoas muscle. Additionally a posterior tilt does not allow the lumbar paraspinals to contract as readily. With proper cueing, the gluteus maximus can then be engaged and stress will be taken off the low back. Enjoy the video- Jim References: Neumann, Donald. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System: Foundations for Rehabilitation. 2nd edition. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier, 2010. 341-342. Print.  Introduction At the Harris Health System, many clinicians practice Shirley Sahrmann's movement impairment syndromes. Utilizing Sahrmann's principles helps guide the clinician toward movement dysfunctions often caused by prolonged postures and repetitive micro-trauma. Since Sahrmann focuses on movement impairments, her syndromes are named using pathokinesiology and kinesiopathology. For the purposes of learning, in this post I will include pathoanatomical diagnoses that relate to lumbar extension rotation syndrome (ERS). Evaluation When performing a lumbar evaluation, assessing for lumbar extension rotation should be a priority. General presentation includes: >55 years old, chronic low back pain, and may be involved in a rotational sport (golf, tennis, etc). On physical examination, you will observe an exaggerated lumbar lordosis, paraspinal muscle asymmetry, excessive pelvic rotation during gait, and hinging during cardinal plane extension testing. They will often complain of unilateral lumbar pain that increases with extension and is relieved with non-weight bearing lumbar flexion.

Clinical Tests In addition to my findings during my functional assessment and observation (stated above), there are many clinical tests used to diagnose lumbar ERS. A few tests I commonly perform are 1) supine bent knee fallout, 2) prone knee bend, 3) quadruped hip extension, and 4) single limb stance. With each of these tests, the examiner should be looking for lumbopelvic compensation (extension and rotation) on the involved side. This compensation generally occurs due to poor timing, coordination, and strength of the core and hip musculature.

Try these tests on a few of your patients and watch how their low back compensates! Let me know if you have any questions or want more information regarding other tests you can perform.

-Jim

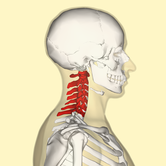

A couple months ago, I subscribed to the premium portion of The Manual Therapist. Dr. E presents a very eclectic approach with various techniques with which I had not been familiar. One of the prime components of Dr. E's assessment and treatment techniques includes repeated loading. While this might be associated with the McKenzie school of thought, his reasoning has more of a neural approach. Since my neck hurt more on one side, I wanted to look for an asymmetry to treat. With cervical retraction and sidebend, both sides were painful, but I was especially limited to the R. Noting the asymmetry, I proceeded to perform repeated motions in the limited direction which resulted in increased range and decreased pain. Part of the theory is that by getting to the end-range repeatedly, we can re-teach the nervous system that it is okay to go in that direction and possibly others. A common saying for McKenzie type exercises is 10 repetitions 6-8 times a day. With Dr. E's approach, the more the motion is performed, the better. This applied to me. I noted the more I did the exercise, the longer I could go without pain and with increased motion. That evening I had my girlfriend do a cervical manipulation and thoracic manipulation which helped my pain, but within 30 minutes, I was back to the prior levels. The next 2 days, I did the cervical retractions and right sidebend 10x every 30 minutes throughout the day (give or take). Each time I did the exercises, I found I could go longer before the pain and stiffness returned. After 48 hours, I was 95% better.

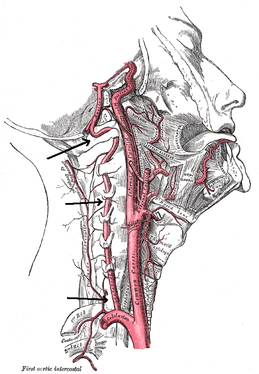

There are two important components I took from this experience. First, repeated loading can be an incredibly useful assessment and treatment technique, when applied properly. With the majority of people being rapid responders, we should get almost immediate changes with pain and/or motion. Secondly, it is frustrating how long we often have to wait for patients to be evaluated due to length of time after referral, lack of awareness of what PT can offer, or other reasons. The sooner patients can access physical therapy, the sooner physical therapy can begin to help patients on the road to recovery. -Chris  There is a common fear in treating the cervical spine (especially the upper portion) manually due to risk of injury. With the potential for damaging the vertebrobasilar artery system in the cervical spine, many people stray away from performing cervical manipulations. There have been a few situations where patients have died of ischemia following a cervical manipulation. The fatal reaction (and associated risk for lawsuit) to something that we can do as health care practitioners may discourage some from learning how to effectively apply manual therapy to the region. Is there really that much risk to injury? And what can we do to assess it? As with any fatalities in the health care system, media (and other professional disciplines) will try to make the public aware of the risk for injury following a treatment. The same case applies to cervical manipulations. Some people have a somewhat irrational fear of this technique following media coverage and word of mouth. But how much risk is there really? NSAIDS have a .0004% annual mortality rate (Vizniak 2015). There is a .00005% chance of dying from a lightning strike each year. With cervical manipulations, there is a .00002% risk of death. This means you are more likely to die from taking NSAIDS or being struck by lightning than a cervical manipulation. That being said, it is essential that proper patient selection is done before even considering this type of treatment technique. Start with patient history. Any patient with ligament laxity, rheumatoid arthritis, long-term corticosteroid use, osteoporosis/-penia, Down's Syndrome, osteoarthritis, and VBI be excluded. Naturally, we should perform our structural integrity tests and blood flow tests. We recently completed a review of the upper cervical spine that may prove beneficial reading as well. The structural integrity tests should at least include Transverse Ligament Test (and/or Sharp Purser Test), Alar Ligament Test, and a test for a Jefferson's Fracture. This last test is completed by compressing the transverse processes of the Atlas to assess for integrity. A positive test will occur with lack of stability or reproduction of neural symptoms. The artery test that is commonly performed is for Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency (VBI). While the test we show displays combined end-range motions, some say this is not necessary. With the manipulation techniques staying closer to mid-ranges, some suggest just performing complete rotation when assessing. In theory, combined rotation and extension significantly closes off the vertebral arteries greater than rotation alone. Now, the real question is: should we perform the Vertebral Artery Test? A compilation of studies revealed that there is a 0% sensitivity and .67-.90% specificity for the test (Cope et al, 1996). What this tells us is that a negative test means absolutely nothing and a positive test means a patient may have VBI. The testing we perform cannot rule out or rule in VBI. Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency is essential to consider as many of the symptoms mimic other orthopaedic cervical spine conditions: headache, neck pain, etc. (along with more traditional VBI symptoms - see link for symptoms). Even though there is poor diagnostic accuracy associated with the Vertebral Artery Test, it is recommended that the test be performed. There is a traditional thought that the vertebrobasilar artery system be tested prior to any manual therapy, no matter how poor the test is. Due to the media's perception that cervical manipulations risk VBI, any sign of "negligence" by not performing the test would likely place blame on the practitioner. As with any treatment technique, evaluate each patient individually for the potential benefit and associated risk factors prior to performing. In addition to performing the VBI test, Jim and I agree that the therapist should perform a pre-manipulative hold prior to any thrust procedure. The pre-manipulative hold allows the therapist to see how the patient will respond to the manipulative position prior to performing the thrust technique. Finally, we recommend following that process up with a "gut check" as well. Is the risk of the technique worth the reward/ benefit the patient will experience? Not everyone needs or should have a manipulation, but there are some instances where it has been shown to be highly beneficial. -Chris References:

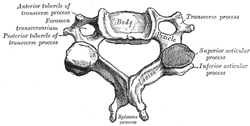

Cote P et al. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1996. Vizniak, Nikita. Spinal Manual. Canada: Professional Health Systems, Inc, 2015. 156-157. Print.  Individuals with mechanical neck pain often have pain and a loss of mobility in the upper cervical spine, specifically at the atlanto-axial (C1-C2) joint. This joint is primarily responsible for cervical rotation, but also contributes to small amounts of flexion and extension. Arthrokinematically, during left rotation, the left facet of the atlas(C1) glides posterior on the axis (C2) & the right facet of the atlas glides anterior. During flexion, the facet of the atlas glides anterior and rolls posterior in relation to the axis. The opposite happens with extension. There are 2 different theories as to how to assess the mobility of C1-C2. At Harris Health, I learned to maximally side bend the head, followed by opposite rotation. For example to assess C1-C2 rotation to the left, maximally side bend the head to the right, followed by maximal rotation to the left. The maximal side bend "locks out" the lower cervical vertebrae allowing for motion only at the C1-C2 junction. The other method to assess C1-C2, which I learned in PT school at St. Louis University, is the flexion- rotation test. To perform this test, maximally flex the cervical spine followed by maximal rotation either left or right. Flexion is thought to lock out all vertebrae below allowing for rotation at C1-C2 only. The difficulty with the flexion-rotation test is maintaining flexion while maximally rotating the upper cervical spine. From my experience, there is a tendency to lose upper cervical flexion. In the residency, I learned that the flexion-rotation test assesses C1-C3. One can then differenciate C1-C2 restrictions from C2-C3 restrictions by first performing the side bend rotation test first, then performing the flexion rotation test. If greater rotation is achieved during the flexion-rotation test vs. the sidebend then rotation, it can be assumed the dysfunction is greater at C1-C2 joint.

It is important to understand that different programs teach different methods of assessment. One method is not better than the next as long as there is sound reasoning behind your decision making. Does anyone else assess C1-C2 differently or have preference with one method over the other? Let us know! -Jim Thank you to the Harris Health Orthopedic Residency for letting me use images from their Cervicothoracic Module Workbook.  Last Tuesday I performed an evaluation on a traumatic C7 Disc Herniation. The 29 year old male presented with neck pain, medial scapular pain, and decreased function of the triceps muscle. This is the first traumatic cervical disc herniation patient I have treated and I thought I would do some research on the topic prior to his 2nd visit. It should be noted that traumatic is different from degenerative disc herniations, a component of DDD, which are present in "30-70% of all adults...as seen on Magnetic Resonance Imaging." As many people know, traumatic cervical disc herniations are seen much less frequently than lumbar disc herniations. This is primarily due to less load bearing requirements of the C-spine, but also in part due to the physiological construct of the cervical disc. The annulus fibrosis, outer ring of the disc, is discontinuous and "does not have complete concentric rings that surround the nucleus." (Neumann 2010) Cervical discs herniate either posterior or posterolateral. They do not typically herniate purely lateral due the uncinate processes blocking this motion. When the disc herniates, it may result in compression of the spinal cord or "radiculopathy, marked by compression and inflammation of the cervical nerve root." With a posterolateral herniation, symptoms include either sharp or dull pain down the medial border of the scapula with radicular symptoms present in a dermatomal pattern of the suspected nerve root. In certain cases, "numbness or tingling may also replace pain as the primary presentation." (Yeung 2012) A physical examination can guide you to a diagnosis, but the best diagnostic test to confirm a disc herniation is a MRI. Treatment of cervical disc herniations is a multimodal approach. Currently there is not a great deal of research regarding treatment options. I plan to treat this individual similar to a cervical radiculopathy patient. I will be using a cervical unloading device while performing active strengthening exercises and the appropriate manual therapy techniques. Additionally, I will be address scapular strength, nerve tension, and postural deficits that were found during the evaluation. More to come, -Jim References: Neumann, Donald A. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System: Foundations for Physical Rehabilitation. St. Louis: Mosby, 2010. Print.

Yeung, Jacky T., John I. Johnson, and Aftab S. Karim. "Cervical Disc Herniation Presenting with Neck Pain and Contralateral Symptoms: A Case Report." Journal of Medical Case Reports 6.1 (2012): 166. Web.  Thoracic Manipulations have received a good amount of attention in the literature in recent years. Whether you are treating a shoulder, cervical spine, or lumbar spine, the thoracic manipulation has been shown to have positive effects on all of these regions. The exact science as to why a manipulation is beneficial is not yet understood, but the most recent evidence suggests that it is multi-factorial. Some proposed effects include: 1) Mechanical- breaking up intra-articular lesions 2) Neurological- stimulates mechanoreceptors & "resets" nocioceptive pathways 3) Hydraulic- change the viscosity of synovial fluid 4) Relaxation- decrease in muscle tone & restore normal blood flow 5) Psychological- both laying hands on the patient & hearing a "pop" are strong influences Below is a quick video on how to perform the the Thoracic Manipulation in Supine. With the supine technique you are flexing the thoracic spine, which makes it a facet gapping technique. The thoracic manipulation can also be performed in prone and seated positions, which can be utilized based on the patient's restriction and position of comfort. As with all manual therapy, it is important to reinforce the treatment with corrective exercises to maintain the positive effects gained from the manual technique. |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed