- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

|

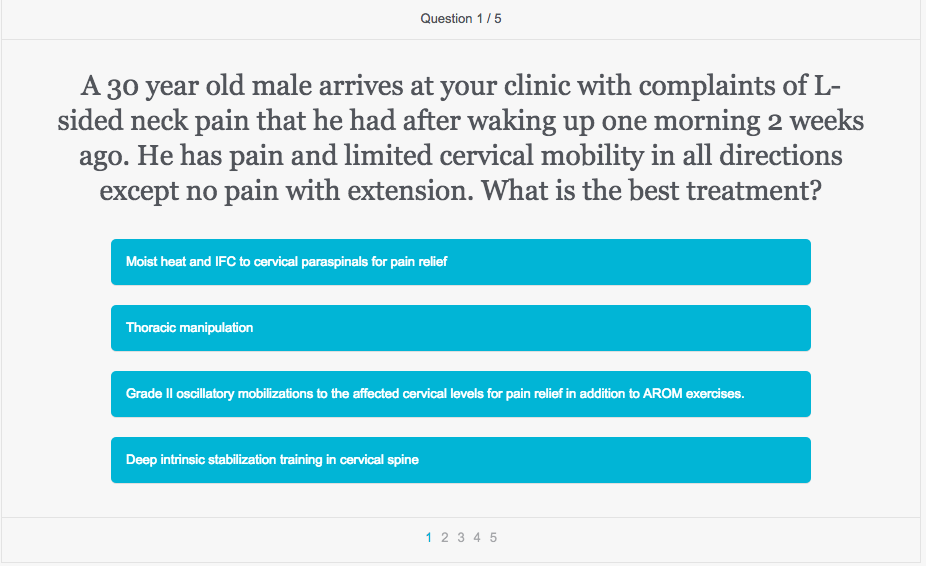

Chris and Jim from TSPT have paired up with OPTIM Manual Therapy Fellowship to make sure you are ready for the OCS examination. Many OCS applicants we have chatted with start their 'intense' studying of the examination around January 1st. This gives them 8-10 weeks of preparation for the March exam. If you have not started already, we highly recommend beginning your preparation. In the meantime, continue to challenge yourself with our weekly OCS Quizzes. Here is Quiz #4. Happy New Year everyone!

1 Comment

The Hyprid Perspective had an interesting post recently about stretching for gymnasts. The author discusses common stretches that gymnasts and their coaches frequently perform and then goes over the reasons behind their faults. A big focus is put on the issue of trying to stretch the hip flexors while in an extended lumbar spine position. This puts the capsule at risk of being stretched, which is not advantageous. While I wouldn't personally focus too much on this pathoanatomical model, the author makes an excellent point regarding incorrect stretching. When looking to stretch a muscle, it is essential that compensations are not permitted as this can put adverse stress on adjacent joints and structures. For example, when trying to stretch the hip flexors, the lumbar spine should either be stabilized in neutral or in flexion so as to not excessively load the lumbar spine into extension. This commonly occurs in gymnasts, which is why they frequently are seen with spondylolistheses. With stretching hamstrings, people often bend forward, trying to touch their toes, while simultaneously going into excessive lumbar flexion. Many patients develop back pain as a result. The takeaway is when looking to stretch a muscle, stabilize the adjacent joints to avoid compensations. Now whether or not we should actually try and stretch is another issue. From my experience, most "flexibility deficits" are actually secondary to either neural tension or relative hypertonicity compared to the antagonist muscle. What does this mean? If a motion is limited by neural tension (when I say neural tension, I am also talking about tightness that is increased with distal/proximal motions - not just patient symptoms), perhaps treatment is needed in the spine, along the path of the nerve or possibly some nerve glides to improve "flexibility." If it appears to be just a "tight muscle," it may be better to try strengthening the antagonist instead, due to some evidence saying we can't affect true muscle length. Regardless, when trying to stretch a muscle, makes sure you stabilize adjacent joints to avoid over-stressing them. -Chris

Like this post? Then check out the Insider Access Page for advanced content! And check out similar posts below!

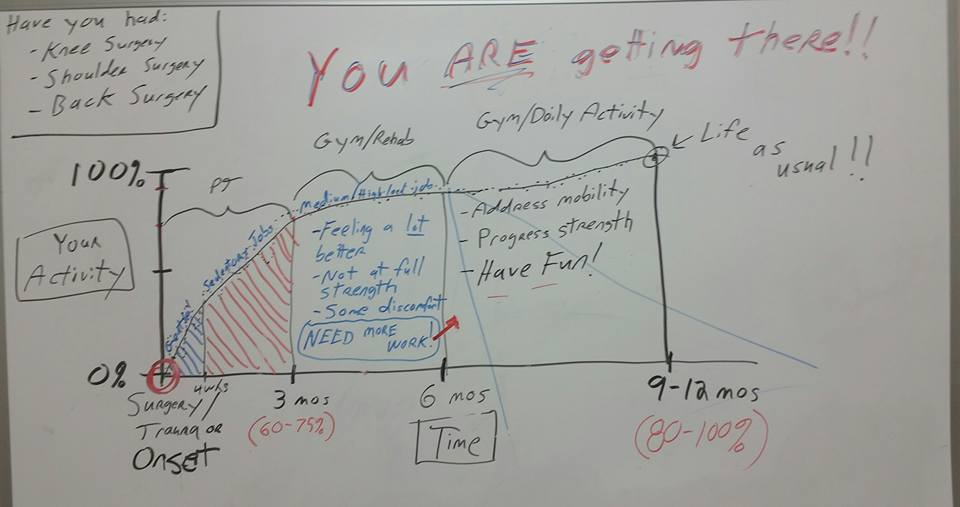

Patients often have unrealistic expectations regarding their rehabilitation prognosis and symptomology throughout each stage of the healing process. Personally I am constantly looking for better visual depictions to explain their prognosis. Rod Henderson, Physical Therapist practicing outside of Houston, TX, uses this graph in his clinic. It is honest, realistic, and easy to follow for patients and healthcare practitioners alike.

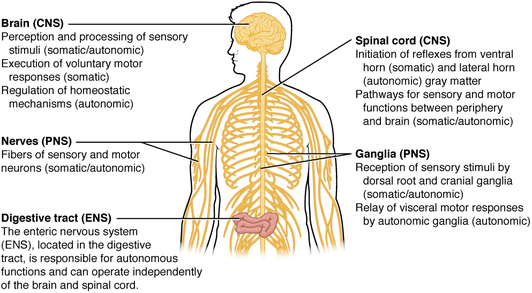

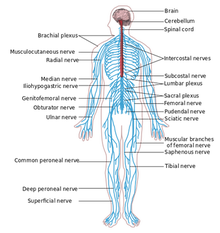

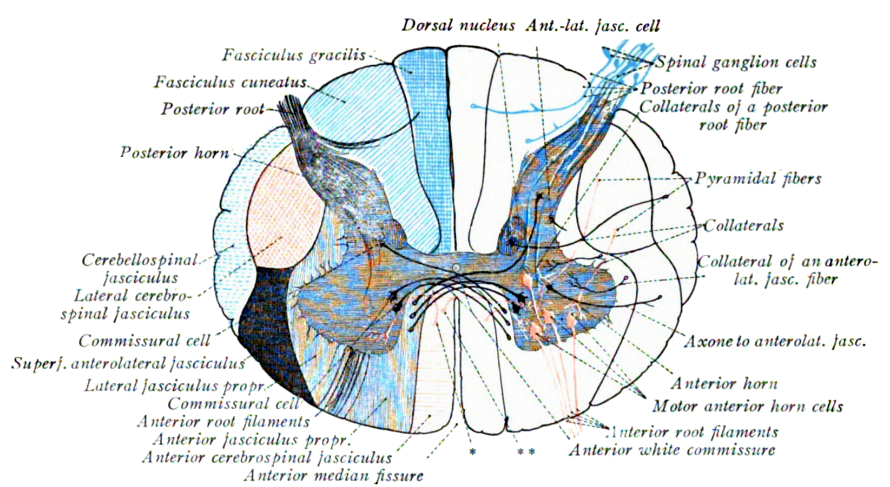

Graph Overview: During the first 12 weeks following trauma or onset of symptoms, patients are generally getting improving. From a physiological perspective, collagen is maturing, remodeling, and getting stronger. In this stage they are almost solely attending physical therapy and performing corrective exercises. At the end of 12 weeks, patients will have gotten 60-75% better. Individuals who perform sedentary jobs should be back at full duty; more strenuous jobs are still on modified duty. From 3-6 months the patient usually begins their normal gym routine while performing rehabilitation concurrently. I generally think of this phase as someone attending PT 1x/week and performing their gym routine 3-4x/week. The individual is starting to feel significantly better, but they have not reached full strength yet. They still have some discomfort (not necessarily pain), but something is 'not quite what it used to be.' Ultimately, they still need more work! From 6-9(12) months, the individual has typically ceased their formal rehabilitation program. They are now performing their normal gym routine and daily activities. The individual continues to progress strength, mobility, flexibility, but now has all the tools needed to be independent. The occasional flare up may occur, but is not anticipated. At the end of the 9-12 months, they should have reached life as usual. Closing Points: I find this graph particularly useful because many patients do not realize how long rehabilitation takes. Most of my patient's have 'high pain tolerances and recover faster than the normal person." Strengthening and retraining movement patterns takes months. Reaching 100% pain free and 'normal' activity generally takes longer than someone anticipates. Being honest and giving appropriate education early on can change a patient's outlook on their condition. Use this graph when educating your patients! Thank you Rod. In Optim's most recent COMT course, we talked about the significance of various kinds of double crush syndrome. For those of you unfamiliar with the topic, double crush syndrome refers to the concept of a nerve being affected at 2 or more separate sites. This can be due to impingement in the spine and neural tension distally. For example, the spinal nerves may be compressed slightly in addition to restricted mobility of the common fibular nerve around the fibular head. With restriction at a proximal region, the nerve becomes more easily affected due to altered blood flow and oxygenation of the nerves distally. Think of it as a "kink" in a water hose. Everything down the line already has less water and will more easily restrict water flow. In the class, we primarily focused on compression of nerves at 2 different locations, as that is what others primarily think of. However, we also discussed the possibility of lifestyle habits contributing to altered neurodynamics. Normal nerve conduction requires approximately 20% of our body's oxygen. Thus, any situation where oxygenation or nutrition is altered can potentially contribute to double crush syndrome. Smoking is one of the most obvious examples. Smoking lowers the oxygenation of our blood and thus decreases how much oxygen our nerves can acquire. It's at this point we should become concerned with nerves having increased susceptibility to damage/abnormal signaling. Another example is altered blood sugar. Diabetes can occur from hyperglycemia. As you may have seen from your clinical experience, patients with diabetes often develop peripheral neuropathy. It is for this reason, we should consider each aspect of our patients' health when addressing the nervous system. So how does this affect our treatment? For starters, we should educate our patients on the impact their diet or bad habits can have their nervous system, and potentially their pain. People don't like to make lifestyle changes often, but pain can be a strong motivator. While we are not experts in nutrition, we can at least point our patients in the right direction. Secondly, in patients with these conditions, it is even more important to address any neural mobility restrictions we find. With poor oxygenation and/or nutrition, nerves are put at risk for injury. Add that to any other restrictions present along the path of the nerve, and our patients are more prone to muscle weaknesses, pain, neural tension, and any other nerve symptoms. We have to improve nerve mobility and health as much as possible. -Chris

Like this post? Then check out the Insider Access Page for advanced content! And check out similar posts below!

Sidelying external rotation is a great exercise for individuals with shoulder pathology. The exercise has been shown to have excellent EMG activity of the posterior shoulder girdle. Additionally shoulder external rotation has been shown to engage the lower trapezius muscle, which is often weak in individuals with shoulder impingement syndrome. Many therapists prescribe sidelying external rotation as an exercise in shoulder rehabilitation, but are we prescribing this exercise appropriately? In this post, I will break down Eric Cressey's sidelying ER video and add my own personal cues. Cues by Eric Cressey: 1) Put a towel under the armpit to place the glenohumeral joint in the proper position. A small towel decreases the stretch placed across the supraspinatus tendon. Additionally, the neutral position allows for better blood flow and healing across the glenohumeral joint optimizing your success with conservative management. 2) Place the scapula in a neutral posture to take stress off the Latissimus dorsi and other shoulder internal rotators. Often times, the glenohumeral joint will rest in downward rotation and depression, inhibiting the rotator cuff muscles. Before strengthening the posterior shoulder, make sure the scapula is in neutral. 3) Manually reposition the shoulder into slight posterior tilt to allow for better muscle activation of the posterior cuff. As I have discussed in previous posts, the serratus anterior and lower trapezius are both posterior tilt muscles of the shoulder girdle. Contrarily the pectoralis minor anteriorly tilts the shoulder blade. Before strengthening the rotator cuff make sure the shoulder is in a slight posterior tilt. -Jim  The OCS examination focuses heavily on the evidence from the clinical practice guidelines (CPGs). As an expert in Orthopedic Physical Therapy, the therapist must know everything from outcome measures, pathology, prognosis, and in-depth anatomy. This quiz covers several of these components. Take the quiz to see if you are prepared for the examination? Check out the OPTIM Website for more information on our courses. Like this post? Check out our Insider Access page for more exclusive information.  What are your favorite Glute and Core Strengthening Exercises We often prescribe glute and core exercises in our clinical practices. Yet year after year I see only 4-5 used by students and residents. I'm a big fan of having a large exercise bank to choose from to make sure we keep things fresh and progressive as needed.  A student of mine recently asked me if I noticed a pattern between patients sitting with their legs crossed and dysfunctional sideglides. I told him I never noticed it, but hadn't really been looking either. The more I thought about it, I remembered I regularly prefer to sit with my R leg crossed over my left. I have a history of dysfunctional sideglides to the L in the lumbar spine, which is equivalent to I prefer to not load the L side of my body. In crossing my R leg over my L, my lumbar spine naturally goes into a R lumbar sidebend, thus, unloading the L side of my lumbar spine. For those of you unfamiliar with the concepts of repeated motions, each joint and the nervous system have a "norm" for stimulation and, when altered regularly, can become symptomatic. The most common example is flexion and extension in the lumbar spine. Most people spend excessive amount of time in lumbar flexion (think about how much we sit, slouch and bend forward) and become hypersensitive with loading the spine in extension, especially with an injury into flexion. As a result, extension becomes both limited and painful. In order to treat this restriction, we have to reset the nervous system back to the "norms" for lumbar extension. The same applies to my personal example. I have a loss of loading on the L side of my lumbar spine and prefer to sit in a cross-legged position that unloads the L side of my lumbar spine. I have also noted that when I stand with my weight shifted to one side, it typically is to unload the L side. How does this apply to you? One thing could be to regularly observe your patients with dysfunctional sideglides if they prefer static postures that unload the involved side. At this point, we need to educate our patients on proper posture and regular body mechanics (and repeated motions), particularly during the symptomatic period. It's not that our patients cannot return to behavior unloading the spine in various directions, but we have to find a balance, especially when in physical therapy. -Chris

Like this post? Then check out the Insider Access Page for advanced content! And check out similar posts below!

With the new year close to beginning, it is getting close to the time when residency applications should start getting sent in, so I thought I would review the pros/cons. It can be a tough decision whether you are just finishing up school or have been practicing for awhile, especially with the salary adjustments, but I believe it is worth it. The primary reason I recommend pursuing a residency is to become a better clinician overall at a faster rate. We often forget that we graduate from physical therapy school as generalists. We know a little about a lot with tools to figure out how to treat most conditions. However, we are by no means specialists. Honestly, I was insecure about my knowledge and skills as an orthopaedic therapist coming out of school and that I would not help many patients. Now, of course, we improve with experience, mentoring and taking various courses, but it takes a long time. In completing a residency, the knowledge and skills are gained at a faster rate. With the advanced didactic and hands on material that is learned in conjunction with 1-on-1 mentoring, the reasoning that may take some to gain in more than a few years can be gained in one. If you look at the medical profession (with which our profession regularly tries to mimic - think white coat ceremonies, doctorate degrees, direct access), residency is required in order to gain the special skills and knowledge for the area of medicine. I recognize there are many issues with the residency process. First of all, there are not nearly enough spaces for all the PT school graduates. It would be difficult to abruptly increase the number of residencies and ensure certain standards. I think there is potentially a place with certain continuing education programs that maybe take a year or so to complete but advance the clinical reasoning and skills in the field. In the orthopaedic specialty, this can be a COMT program, McKenzie, SFMA, PRI, or many others. There are similar type programs for each specialty. Another issue typically is cost. While, residencies themselves are not an option for all due to the pay cut, the continuing education programs discussed before can help to mediate those costs at a much more affordable rate. There are many different types of clinical development programs from which to choose. The three of us chose residencies. Jim was at Harris Health's orthopaedic residency, Brian at USC's sports residency, and myself at Scottsdale Healthcare's (now Honor Health) orthopaedic residency. For a list of the available residencies, check out this link from the APTA.. Below you will see a couple different links we have had about our residency experience, but please don't hesitate to contact any of us in either making a decision about applying to a residency or the process itself. -Chris

Like this post? Then check out the Insider Access Page for advanced content! And check out similar posts below!

The OCS examination is held every year at the beginning of March. OPTIM Physical Therapy works hard to prepare our students for the exam. Enroll in one of our courses to help you get ready for your orthopedic specialty exam. Take the second quiz now!.

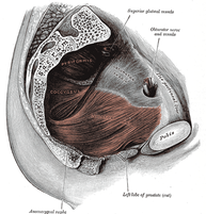

In previous posts, we have talked about how to prepare for the OCS. Check those out HERE & HERE.  One of the critiques I have heard about the Selective Functional Movement Assessment (SFMA) is how unrealistic it is for people to complete a proper squat. In Gray Cook's Movement, he discusses how if you look at 3rd world countries, the majority of people (even elderly individuals) can still assume the deep squat position. The reason is that they don't have the indoor plumbing we have and must complete a bowel movement by doing a deep squat. If you look at babies, they perform deep squats without any issues. It is part of our normal development as humans. Not only do some individuals go to the bathroom in the deep squat position because they don't have toilets, but it also is beneficial for our gastrointestinal system. In the video below, you will note that the colon actually becomes constricted in the posture acquired when using the toilet due to the abnormal pull on the puborectalis. By sitting in a deep squat, the muscle relaxes and restriction is removed from the colon. As the video discusses, this may play a role in why 1st world countries have so many gastrointestinal issues. With what we are learning about squat position and going to the bathroom, it's not just crossfitters that should be concerned with squat depth, but the entire population. It may be that trying to improve the squat form and depth should become a preventative measure. It's another sign that our sedentary lifestyle plays a significant role with the many degenerative conditions in 1st world countries. In addition to improving squat depth, perhaps we should be more proactive in issuing devices like the one shown below to help with completing a bowel movement, especially in those with low back pain and/or pelvic floor dysfunction. -Chris

Like this post? Then check out the Insider Access Page for advanced content! And check out similar posts below!

|

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed