- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

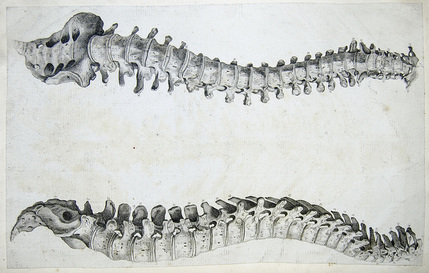

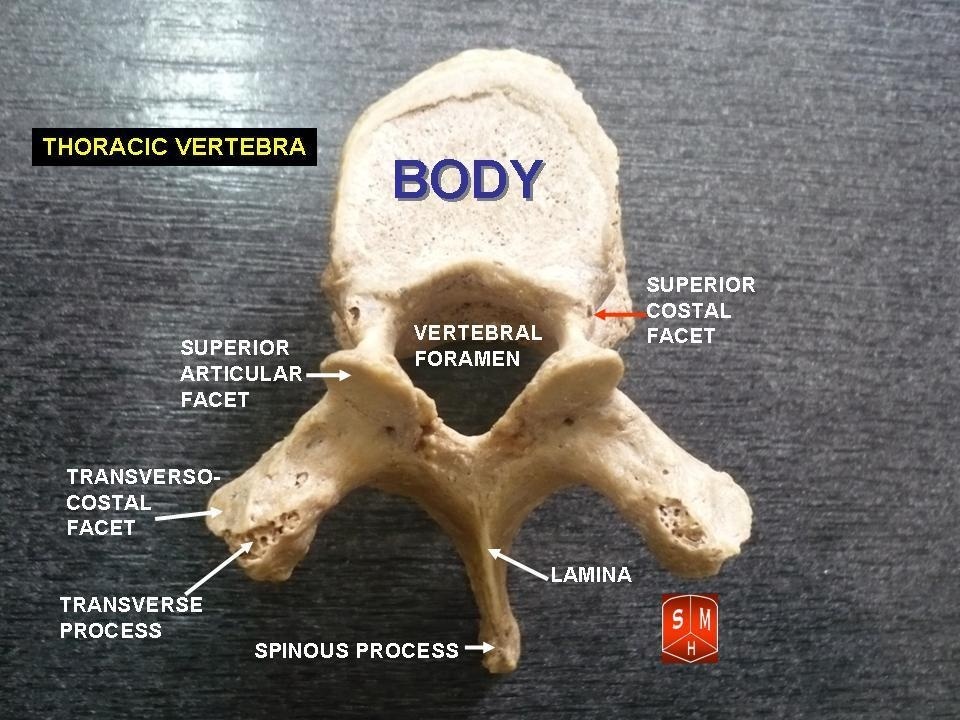

I often hear the terminology open-packed and close-packed joint positions used in the clinic. In general, clinicians know to mobilize in the open-packed position and avoid manipulation in a close-packed position, but what else should we know about these terms? Is there any other clinical significance to the open v. close-packed positions? In this post I will review these 2 positions and discuss the clinical relevance of each.

How Should PT's Interpret Open vs Close-Packed Clinically? As I mentioned above, it is important to start your joint assessment and treatment in the open-packed position. Since the joint has the most available room for movement, mobilizations are best tolerated in this position. For example, the open-packed position of the knee is 25 degrees of flexion. The close-packed position is full extension. At 25 degrees of flexion the knee is loose- one can assess varus and valgus ligament stress testing or check tibial IR/ER mobility in this position. Biomechanically, the knee is 'unlocked.' Following an injury, the body favors this position because there is space for swelling and other fluid to accumulate within the joint. As the patient's ROM improves, pain decreases, and the swelling subsides, the clinician can start to mobilize the joint in other positions of flexion and extension as needed. Additionally, understanding the open and closed packed positions is essential when performing manipulations. We want to manipulate a joint in the open-packed position, but often times we cannot target a specific joint unless we lock out or close-pack the surrounding joints. For example, when performing a prone SIJ distraction manipulation, the hip needs to be placed in extension, abduction, and internal rotation. These three movements are the close-packed position of the hip joint. You must lock out the hip so you do not manipulate it when you are targeting the SIJ. Each joint has a different open and close packed position and being able to quickly recall that position will make you a more efficient clinician. If you do not understand the open and close-packed positions of regional joints, the specificity of your techniques will decrease. Jim

13 Comments

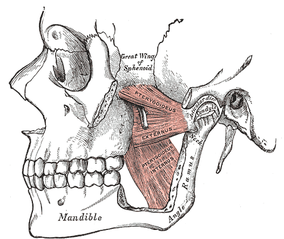

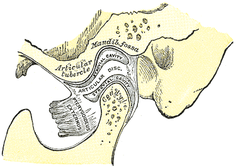

My clinic recently had an inservice by a dentist about restricted airways and the possible contribution to TMJ dysfunction. As physical therapists, we are seeing an increase in the amount of referrals for Temporomandibular Dysfunction (TMD), due to its relation to cervical issues. Long have we known about the link between forward head posture and decreased diameter for our airways. This is typically treated with postural education. Another component of TMD includes parafunctional habits, such as chewing gum, bruxting, and grinding teeth. Dentists treat this with relaxation training and mouth guards when sleeping. But why do people grind their teeth? In the lecture, the dentist reported that a lot of the recent research suggests there is a link between disturbed sleep and TMD. With the abnormal sleep patterns, there is increased muscle activity, including the TMJ muscles. This activity may include grinding of the teeth, which is why the night guards are often prescribed. But are we treating the symptom or the cause? There are theories that the sleep patterns become dysfunctional due to a lack of oxygen. Restricted nasal passages are often overlooked. Try breathing through one nostril and see if there is a difference compared to the other side. This or a restricted air passageway in the neck could be significant contributions that we cannot treat. This leads us back to the discussion about night guards. With the presence of a night guard, the tongue is positioned in a way that increases the airway restriction. In treating the symptom, we may actually be worsening the disorder. With the impact sleep (or lack thereof) has on all diseases and things like chronic pain, we have to regularly review and improve upon our treatment of any disorder that can affect sleep. If you come across any patients with TMD, be sure to ask about any breathing issues or waking up out of breath. These patient in particular may benefit from referral to a ENT physician or at least a dentist that is skilled in treating TMD. -Chris Like this post? Then check out the Insider Access Page for advanced content! And check out similar posts below!

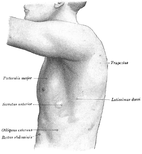

The serratus anterior (SA) muscle is vitally important for shoulder function. The muscle is best known for it's role in scapular upward rotation and posterior tilting of the scapula during shoulder movements. Additionally, it works in conjunction with the upper trapezius as a force couple to achieve full shoulder elevation. The SA is often weak in many of my patients with shoulder dysfunction. The reason for this is multi-fold. Two common reasons for SA weakness include: 1. anterior tilting of the scapula secondary tightness pec muscles & 2. over-dominant downward rotators. Both of these causes can be attributed in part to chronic postural positioning. With anterior tilting of the scapula, the shoulder is placed in an anterior and internally rotated position, lengthening the SA and inhibiting its function. With over-dominant downward rotators, the forward head posture stresses the upper cervical spine creating tension in the levator scapulae and rhomboids. Again, this posture facilitates the downward rotators, making full upward rotation difficult to achieve.  Testing the Strength of the Serratus Anterior Supporting the arm on your shoulder, passively flex the arm to 110 degrees and protract the scapula. Monitor inferior scapular angle. Ask the patient to maintain this position as you release the arm If not, apply a downward force proximal to the elbow. If the scapula jogs underneath your fingers, the test is graded <3-/5. Strengthening the SA Muscle A 2006 JOSPT article entitled, "A Comparison of Serratus Anterior Activation During a Wall Slide Exercise and Other Traditional Exercises" found that the wall slide exercise was an effective exercises for SA strengthening. The article also found that the push-up plus exercise had good activation at 90 degrees of shoulder flexion. Clinically, I prefer to have my patients perform wall slides over the push-up plus. As I mentioned earlier, the SA helps the shoulder reach full upward rotation. The wall slides exercise allows for SA activation through the entire range of motion. Below is a video of several exercises by our author Chris Fox for strengthening the SA. -Jim  Joint mobilization and manipulation is an excellent tool for improving mobility and pain for patients. The effects also can include increased muscle function, improved sensation and more. One of the issues that can be seen, however, is that patients may come back repeatedly with the same joint restrictions, requiring continued manual work. This is where it’s important that we follow up our manual techniques with some sort of exercise to lock in the changes. I typically use a form of repeated motions to maintain and often increase joint restrictions. A common area of impairment and restricted mobility is the CT junction. On our Insider Access Page, we have reviewed quite a few manual techniques for increasing CT junction mobility, but maintaining those mobility improvements is especially difficult due to common postural faults. As you likely have seen in the clinic, people tend to sit with a forward head posture frequently which results in prolonged time spine spine in the upper thoracic flexion. When the extension mobility is not used, the patient tends to become increasingly stiff in that region. In the past, I have given repeated cervical retraction with extension to focus the motion at the CT junction, when symptoms and restrictions are bilateral or central. When symptoms are unilateral, I’ll check cervical retraction (full retraction!) with sidebend and look for a passive and active asymmetry. The patient then can do repeated cervical retraction with SB for repeated loading. When used properly, the exercise is extremely effective, however, I often find patients have a difficult time maintaining full retraction during the exercise. As a result, they fail to mobilize the lower cervical spine. Recently I have been using a modification for self mobilization of the CT region. The lower cervical spine and thoracic spine have ipsilateral coupling. This means that sidebending and rotation occur at the same side with loading due to facet alignment. This can be utilized during mobilization by rotating to the restricted side fully and then sidebending ipsilaterally. I have found this technique is very effective in increasing CT junction mobility and patients are less likely to perform the technique incorrectly. Check out the video below for an exact demonstration of the technique. -Chris

Like this post? Then check out the Insider Access Page for advanced content! And check out similar posts below!

I was recently reading a 2012 article from the Forward Thinking PT titled, "Drop the plumb line...static posture assessments were so last decade." In the post, the author discusses how he does not use static postural assessments because the abnormalities that clinicians find are not truly abnormalities, but rather differences. Additionally, he states that visual examination and assessment are insufficient to make clinical decisions. The author sites several research articles that support the belief that habitual patterns are not related to musculosketal pathology. The most profound article (in my opinion) that he cites recommends that physical therapists should not perform abdominal muscle strengthening in individuals with chronic low back pain based solely on relaxed standing posture. Reading the Forward Thinking PT article may seem daunting for many physical therapists. Almost every therapist I encounter assesses static posture. Many follow the notion that good posture will minimize microtrauma across the joints and decrease the incidence of musculoskeletal injury. In theory, an individual's static posture will alter muscle length and tension, which will alter their movement patterns. Shirley Sahrmann founded much of her Movement Impairments Syndromes off this belief. For example, an individual with increased lumbar lordosis likely have weak abdominal muscles and will need motor control exercises to control the lumbar spine during functional movements. If that patient chronically rests in lumbar lordosis, one would assume they are at an increased risk of injury. Changing the static posture would be a logical starting point to affecting their pain.  My Thoughts on the Subject Based on the cited research, the Forward Thinking PT article is correct. A pure static assessment has not shown to be a reliable measure for choosing your treatment options. Fortunately, we rarely treat based off static movement assessment alone. The articles provided do not address functional movements. I agree with the author that clinical decisions should not be based on a static snapshot. Personally, I am more concerned with how the patient moves. With that said, I often use static postural assessment as a baseline to guide which functional tasks I want the patient to perform. For example, if a patient has a forward head, rounded shoulder posture, I know I want to see their overhead flexion. The forward head presentation cues me to assess the mobility of the CTJ, the strength of the DNF, and strength of the low trap. These impairments are likely the biomechanical contributors to the pain. Addressing the biomechanical contributors is often successful, BUT not always. As the Forward Thinking PT points out, we also need to address the patient's perception of pain. We need to change the patient's perceived threat of pain and reprogram the brain to decrease the threat of injury. This can be addressed by performing repeated motions, manual therapy, graded exercises, and neuroscience education. Along with these interventions educating on proper posture is essential, especially during the acute phases. In conclusion, we need to combine the biomechanical approach with the biopsychosocial and pain matrix approaches. Normalizing postural mechanics both statically and dynamically will decrease the stress placed across the musculoskeletal system and prevent re injury from occurring. Additionally, we must change how the brain perceives pain. If we do not change the perception of pain, we will not be successful. Thank you Forward Thinking PT for the thought provoking article! I enjoy reading all your content. Jim One More Position Open in the OPTIM COMT Scottsdale Program.

Check out the program website for more information! Send us an email if you are interested! Ever since the beginning of physical therapy as a profession, physical therapists have been viewed as an ancillary service or extension of the doctor. In years past, this was absolutely true. The training of a physical therapist was far inferior to that of a medical doctor. More recently, the education requirements of physical therapists have increased, leading to a push for access as primary care. Physical therapists are clamoring to be viewed on or near the same level as the medical doctor. Should this be the case? Whether or not physical therapists are prepared for this is debatable. In general, one of the requirements in switching to the doctoral degree was to improve the differential diagnosis skills as a physical therapist. While this has without a doubt improved, the consistency of being able to recognize non-musculoskeletal disorders may not be as great as desired. This can be improved with residency training. Ideally all PT's would go through residency training; however, not nearly enough residencies are available. Maybe there can be some alternative step after PT school that could simulate what doctors go through in their residency training, but be more accessible to PT's. If we want to be viewed on the same level as medical doctors, I believe there is a bigger issue that needs to be addressed - how we treat pain. Much of the recent research regarding pain science has consistently showed a lack of correlation between anatomical "pathology" and pain. There have been numerous studies showing asymptomatic individuals with pathological findings in their spine and other joints. I bring this up, because many doctors (not just orthopaedic surgeons) continue to attribute pain to the pathoanatomical theory. The relationship between pain and the nervous system is inconsistently understood. Many practitioners misinterpret that pain is a sensation (via "pain fibers") and not realize that it is actually a perception. The studies showing inconsistencies in imaging findings are taken but then interpreted that the findings are only significant if they match the patient's pain complaints. While this is a step in the right direction, it continues to have a pathoanatomical basis. If this were completely true, a patient with L-sided radicular pain would not have complete resolution with repeated loading on the involved side! The pain patients experience is more associated with a hypersensitization of the nervous system and can be managed by finding a way to down-regulate it. Why do I bring up the pain issue? Because the AMA holds a monopoly on the development of health care policy, it is more so the medical profession that must be convinced of physical therapy's ability to increase their direct access. Before we can convince others organizations, we need to have consistency amongst our profession. Many of the "top physical therapists" build their therapeutic model off the pathoanatomical theory as well, leading to professional organizations promoting these ideas. Even as research regularly is coming out that should push us away from that model, many PT's cling to it. There is success with treating via the biomechanical approach, but is it the most effective? In trying to increase the relevance of physical therapy as a profession in primary care, we need to promote the same ideas and philosophies if we expect to be the provider of choice for musculoskeletal pathology. -Chris

Like this post? Then check out the Insider Access Page for advanced content! And check out similar posts below!

In the past few weeks, I have been treating several patients following lateral ankle sprains and s/p ankle fractures. Following an ankle injury, almost all patient's experience decreased dorsiflexion range of motion and decreased plantarflexor muscle (gastrocsoleus complex) strength. Recently one of my patients has began reporting low back pain and neural tension down the affected lower extremity. While he had positive neural tension for the tibial nerve and hypomobility of his lumbar spine, the cause of the dysfunction was his movement pattern when performing calf raises. Like this post? Check out exclusive information on our Insider Access page. What Can You Do Clinically?

1) Inquire about a previous history of low back pain or leg injury during the initial visit. A previous injury predisposes the patient to future injury. The gentleman I have been treating in the example above had a long standing history of lumbar pain. It was not his 'greatest impairment' at the time of the evaluation, so he failed to mention it and I failed to inquire about it. 2) Train from the trunk down when performing ankle exercises. When performing calf raises, make sure your patients are in a neutral lumbar spine. Ensure their hips are not in adduction or internal rotation and they are not collapsing into pronation or excessive supination. I often have my patients start performing calf raises with their feet together to minimize these compensations. If the patient retrains the muscles from a poor staring position, these same compensations will exist during functional movements. 3) Do not be afraid to breakdown an exercise if compensations exist. For example, if the patient cannot perform a single calf raise without over-engaging his lumbar paraspinals, have the patient perform supine theraband calf presses with a posterior pelvic tilt and TrA activation. They must demonstrate control of the entire movement pattern not just the isolated muscle. Jim

One of the goals of clinical development as a physical therapist is recognizing the source of the problem and not just treating the symptoms. For example, if a shoulder hurts but the thoracic spine is not moving sufficiently, we want to include the thoracic spine in our management. If a knee is hurting during walking because of poor dorsiflexion mobility, we want to treat the dorsiflexion restriction. If a person cannot touch their toes because of poor lumbar flexion, it may be that proper motor control is lacking. Whatever the issue, we must be thorough with our examination to identify all contributing factors and the primary driving force. One variation of this I regularly see is spinal mobility restrictions and neural tension. I typically will address both in the same treatment session, but often I will notice that neural tension will be eliminated or significantly decreased following treatment to the spine. This may include a manipulation, IASTM or repeated motions. Because of this, I rarely give nerve glides as an exercise for home. That doesn't mean nerve glides aren't effective. Even after treatment to the spine, some nerve tension can remain and be improved upon by addressing the neural tubes. In fact, I have come across patients that have greater responses to nerve glides than spinal treatment. This may be the case in your patients who inappropriately try "stretching their hamstrings" when neural tension is the issue. The nerve glides may be a novel movement to the peripheral nervous system, especially if there are greater restrictions peripherally. Because of this, your patients may express significant relief of pain and improvements in mobility following treatment. As far as specific treatment goes, I recommend IASTM to the paraspinals of the innervating segments and anywhere along the path of the peripheral nerves. The joints that are crossed by the nerves and from which the nerve originate can be manipulated if restricted (or use other techniques like repeated motions). Additionally, think about addressing any tension points. I often will manipulate T6 for both upper and lower quarter patients and the TL junction for lower quarter patients. When addressing nerve mobility, glides and tensioners are often used. Both are effective, but glides have been shown to have greater nerve excursion (Coppieters and Butler, 2008). While I prefer to use nerve glides myself, I will use tensioners if performing a glide is difficult. I should note that occasionally you will come across a patient that has adverse reactions to nerve tensioning. Aside from cauda equina syndrome and tethered cord syndrome, you should be careful with patients that are significantly centrally sensitized. You'll notice your patient feels worse following the treatment. I have found these patients have a high fear avoidance behavior, anxiety, or significant neural tension. In these cases, use your other methods to address nerve mobility restrictions. -Chris Reference: Coppieters MW1, Butler DS. (2008). Do 'sliders' slide and 'tensioners' tension? An analysis of neurodynamic techniques and considerations regarding their application. Man Ther. 2008 Jun;13(3):213-21.

Like this post? Then check out the Insider Access Page for advanced content! And check out similar posts below!

|

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed