- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

Overview FAI is a common pathoanatomic problem due to abnormal contact between the femoral head and acetabular rim. In a normal hip, the femur translates in the acetabulum without interruption. Stresses are dissipated throughout the labrum, minimizing the risk of breakdown. In FAI, abnormal stresses are placed between the femoral head/neck and the acetabular rim. These abnormal stresses are the sensation of 'impingement' the patient reports when you bring them into hip flexion or IR. The source of pain can either be due to abnormal shape of the femoral head-neck junction (Cam-type) or more prominent acetabular rim (Pincer-type).

Both cam and pincer lesions clinically present with groin pain during or after flexion type movements. They have increased pain with sitting due to ROM impairments in hip flexion and internal rotation. Upon functional assessment, gait abnormalities may be present as well as deviations with squatting movements. Due to the abnormal shape of the femoral head or acetabulum, labral tears and cartilage breakdown is usually the result of FAI. To diagnose FAI, imaging is required. Clinically, the labral anterior impingement test or labral posterior impingement test can be used to assist the therapist understanding what structure is involved. As with all things physical therapy, we cannot change the anatomy, but knowing an individual has FAI will give us a better understanding of how to treat their movement dysfunction.

-Jim

2 Comments

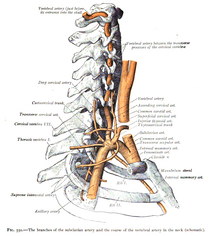

With the physical therapist's increased emphasis on incorporation of manual therapy when treating the cervical spine, the concern of vertebrobasilar insufficiency is frequently discussed. Even though fewer people have adverse effects from cervical manipulations compared to NSAID's, there is still a stigma revolving around the disease, and rightfully so. Part of the reason the incidence of adverse effects following cervical treatment is due to appropriate screening methods. We all know that the Vertebral Artery test has insufficient psychometric properties for diagnosis. If a test is negative, it doesn't change anything. If it is positive, the patient might have VBI. The sensitivity and specificity of the test is so low that some clinicians actually prefer not using the test. Personally, I still use it, due to the public perception that it is required for "screening"; however, I consider the diagnostic accuracy in my clinical reasoning. What is more beneficial in the screening process is a thorough subjective history. There are signs and symptoms that increase the likelihood of the patient having the disease. We should be asking about nausea and vomiting, the 5 d's (dizziness, drop attacks, diploplia, dysphagia, dysarthria), and look for nystagmus. Also, consider other past medical history like cardiovascular disease. Most programs and manual therapy classes spend time going through how to properly take the subjective and what to look for when determining the likelihood of VBI. So what do you do when both the subjective and objective are ruling in VBI? I recently had a patient with "neck pain" come to my clinic for an evaluation. I noticed immediately that the patient had a sense of caution when turning her neck. She described her neck pain extremely vaguely on both sides of her cervical spine and upper trap. As part of my screening process for upper quarter patients, I ask about dizziness, N&V, and a few other questions that are linked to various pathologies. The patient reported she did have some dizziness when turning her head and changing positions. Initially I suspected BPPV, but also wanted to continue exploring other possible symptoms. The patient reported dizziness, fainting, blurred vision when turning her head, and difficulty forming words occasionally. That is 4/5 D's and she ended up having positive nystagmus with full cervical rotation after about 10 seconds which also recreated her dizziness. The patient apparently never told the doctor about her dizziness, fainting, or trouble speaking because she thought they were unrelated. Additionally, the patient reported a history of HTN and was in her upper 50's. Having never actually encountered someone with a collection of these S&S that may be associated with VBI, I knew I would not perform treatment without further work-up by the physician. I called her doctor and they wanted her to come in that day. I was unsure; however, if, had I not been able to get a hold of the doctor, should I have sent her to the ER. She had been walking around with these symptoms for 6 months, but with the risk for stroke, should we be referring these patients to the ER? It is a tough decision that may be based on each patient's individual presentation. We don't want to send any patient with neck pain and dizziness to the hospital. A single "red flag" does not have much clinical value, but a collection of them does and we need to act appropriately. What do you think is the next correct step? -Chris While studying for the OCS exam, finding visual references can be a savior. One component of my studying has been gaining a deeper understanding of the various plexus' throughout the body. While studying I came across this animation video below discussing the brachial plexus. The brachial plexus supplies sensory and motor innervation to the shoulder, arm, forearm, and hand. Understanding the structure and anatomy of the brachial plexus makes differential diagnosis much more manageable. Key Points from the video below: -Brachial plexus is compiled from the spinal segments C5-T1 -The brachial plexus has roots, trunks, divisions, cords, and terminal branches (the acronym Remember To Drink Cold Beer can help remember this order.) -The 3 trunks are the upper (C5-C6), middle (C7 alone) and lower (C8-T1). -Each trunk has an anterior and posterior division. All anterior divisions innervate anterior compartment muscles. Posterior divisions innervate posterior muscles. -The 3 posterior divisions form the posterior trunk (easy to remember) -The 2 anterior divisions from the upper and middle trunks form the lateral cord. -The 1 anterior division from the lower trunk forms the medial cord. -Cords are named relative to the position of the axillary artery. -The 5 terminal branches are musculocutaneous, axillary, radial, median, and ulnar nerves (The letters MARMU can help remember the branches in order. -No smaller nerves arise directly from the divisions. -The posterior cord gives rise to 7 nerves, one of which is the medial subscapular nerve also known as the thoracodorsal nerve. I recommend watching this video 2-3x so you do not miss any of the clinical pearls present. If you have any other great visual aids you use in your studies send them my way! It would be much appreciated. Enjoy.

-Jim Heafner A couple weeks ago, I did a post on the Manual Muscle Test of the Serratus Anterior. The muscle is very frequently insufficient, which can be a significant impairment for shoulder dysfunction. The role the Serratus Anterior plays for upward rotation of the scapula is imperative. Several of the comments recommended a couple excellent exercises for training the muscle. Below is a video reviewing those suggestions, along with a couple additional exercises that I like to use. Enjoy! *Edit: there is a point in the video where I say "mid-cervical spine" which should be "mid-thoracic" -Chris For more videos like this, check out The Student Physical Therapist Premium Page!

It seems that everyday I treat more and more nerve dysfunction. Currently I am treating 3 different individuals who were referred to me for 'lateral epicondylagia' but additionally have radial nerve dysfunction with upper quarter deficits. Whether it is a double crush syndrome, an isolated peripheral nerve problem, or a radiculopathy, understanding the anatomy and course of each nerve is important to proper treatment. Quick Facts regarding the Radial Nerve: -The radial nerve arises from the posterior cord and receives branches from C5-T1. -The nerve gives off 3 branches in the axilla- 1. branch to the long head of the triceps, 2. branch to medial head of triceps, and 3. the posterior cutaneous nerve of the arm. -The nerve travels through the triangular interval and runs through the spiral groove of the humerus. -The radial nerve provides sensory input to most of the dorsal aspect of the upper and lower arm. -The nerve is susceptible to injury in distal humerus fractures which can cause wrist drop. -The nerve branches in the posterior interosseus nerve, supplying the radial dorsal forearm musculature (this nerve does not provide sensory input; PIN=purely motor). -The superficial radial nerve runs into the hand providing sensory input the dorsum of the hand. To see treatment of radial nerve dysfunction, check out my case from earlier this year. It discusses a patient with radial nerve tension with CT junction mobility deficits. The patient was originally diagnosed with lateral epicondylagia and stopped attending PT because he knew the cause of the problem was not being addressed. Do not be the PT who is missing these cases!

Check out that post OR more great information on nerve tension and assessment on our PREMIUM PAGE! Jim  I often have patients complain about the "creaking" in their various joints. Whether it be the knee, neck, foot, or any body part, patients often voice concern. I, personally, have never done much reading on crepitus and the correlation to pain/disease, but with the advancements in pain science lately, I have regularly educated patients on not being concerned with the noises, especially since they are often not painful. Claire Robertson recently did a review on the literature surrounding crepitus. The current understanding is that crepitus is unrelated to pathology and is a part of the normal aging process. It is already becoming more and more apparent how little correlation there is between imaging findings such as herniated discs, meniscal tears, RTC tears, OA, etc. and patient symptoms/function. But many patients present with a level of apprehension regarding abnormal imaging findings and crepitus. It is up to us as clinicians to properly educate our patient on normal aging of the body and pain science. -Chris Last week I was treating a young gentlemen for his second physical therapy visit (the initial evaluation was performed by a different physical therapist.) The young man presented with low back pain with right lower extremity numbness and tingling and occasional left lower extremity symptoms down to his knee as well. Prior to starting treatment, the gentleman heard that I perform manipulation often & felt like his low back needed to be popped. In my head, I was thinking this would likely be an option, but I wanted to recheck his status from the initial evaluation first.

Per the initial evaluation note, the only unusual finding was hyperreflexia (3+) on the R. Due to this neurological finding, I chose to perform my complete neurological screening. My second visit findings were: Reflexes: Patellar: Right: 4+ (elicited while tapping quadriceps), Left: 3+ Achilles: Right: 2+, Left: 2+ Myotomes: Weakness on Right S1 (I also checked heel walking and toe walking which looked abnormal, but the patient had a unique compensation pattern.) Dermatomes: WNL Clonus: Right: 20 beats; Left: 4 beats Babinski: Inconclusive (no toe movement) Delving further into a subjective, he denied changes in bowel and bladder, denied recent constitutional signs and symptoms, or unusual weakness or fatigue. He reported no significant PMH, except his mother has multiple sclerosis. At the point, I knew I had enough findings NOT to treat this gentleman. Fortunately, I work at Concentra and our medical providers are within the same building. I had this patient seen that same day by the medical providers who have ordered an MRI. The purpose of this post is to always reassess your patient's status to ensure they are appropriate for your care. If I would have chose to manipulate this patient, I could have caused further injury. Always reassess! -Jim  At my clinic, we offer a rapid referral system where we provide free screens for patients in order to determine either a need for skilled physical therapy or possible referral to another practitioner. Recently, I had a 12 year old boy come for a screening due to knee pain. The patient reported that he had been practicing kicking footballs when on one kick, he felt a "pop" and developed severe knee pain in the planted leg. The patient denied any hx of knee pain prior to the incident. Pain was located over the tibial tuberosity and painful with palpation. Pain could also be increased with squatting or jumping and decreased with rest. CONTINUE READING... -Chris |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed