- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

|

As many of you know, we recently launched a Home Exercise Portion to our website. They consist of many exercises that we prescribe and programs like VHI don't contain. I wanted to highlight one exercise today, the Quad Rock Back, because of all of uses for it. The exercise is a staple of the Shirley Sahrmann philosophy. While it is listed under the "Low Back" section, it is often prescribed for cervical, shoulder, and hip patients as well. We will break down how the exercise can be used for each region. As described in the video, when this exercise is performed for cervical patients, often the head begins to extend or flex while rocking back. This is a result of abnormal movement and compensatory patterns in the cervical spine. For cervical spine patients, we encourage a chin tuck so that no neck movement occurs during the rocking.

There are many reasons why I like to give this exercise to shoulder and hip patients, one being joint compression. We are taught in our manual therapy classes that joint compression can be beneficial for healing; it also can help mobilize the posterior capsule. It also helps mimic the developmental patterns of weight bearing on the upper extremities, and thus is a critical part of rehabilitation. Additionally, the quad rock back exercise can be use to help normalize scapulohumeral movement patterns and avoid any compensatory activity. While performing the exercise, the movement can be completed by actively flexing the hips, instead of pushing away with the UE's. This allows the shoulder to move in a more normal pattern. Similarly, the exercise can help with unwanted hip musculature activity. By reversing the directions (instructing the patient to push with the hands and not actively flex the hips), the patient can decrease abnormal femoral head sliding and thus compete hip flexion less painfully. The exercise can be used both for treating and assessing and low back dysfunctions, and not just because it is one of the more comfortable positions for low back pain. If you take your patient into quadruped and have them rock back, pay attention to the pelvis, hips, and low back. You may note a deviation to one side, suggesting increased muscle activity, stiffness, or movement patterns. Often you will note premature lumbar flexion compared to end-range hip flexion. This is secondary to all the sitting we do throughout the day - our lumbar spine becomes more flexible compared to the hip! By encouraging the patient to maintain a stable lumbar spine while rocking back (this can be done by placing a stick across the low back - if it falls off, we know there has been abnormal movement). This teaches our patients to isolate hip movement from back movement. While I may not subscribe to all of Sahrmann's theories on movement impairment syndromes, especially in the acute phase, I do appreciate the focus she places on changing compensatory patterns with her exercises. Many of these patterns stem from abnormal postures or repetitive tasks that we perform throughout our daily lives. The rehab focuses on resisting any changes in movement that occur as a result. I have found that I get better results with incorporating repeated motions into my treatment, but I continued to use Sahrmann exercises to try and retrain movement afterwords. -Chris

1 Comment

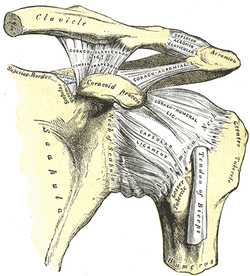

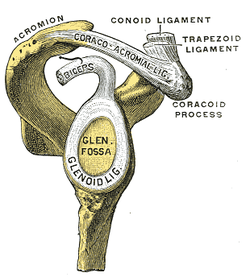

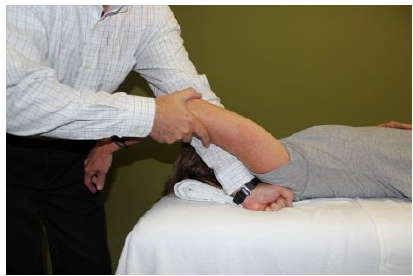

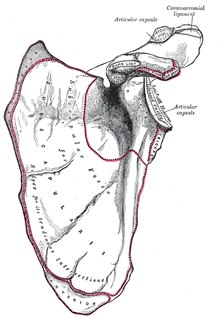

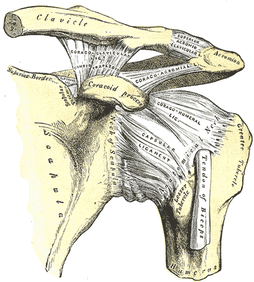

General Overview Acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) injuries are quite prevalent throughout the general population and specifically in the athletic population. In 2012 Harris et al found that ACJ disease was present in 31% of individuals who presented with shoulder pain. (Harris 2012) The ACJ is a synovial joint which connects the distal clavicle to the acromion process. The joint assists the scapulothoracic joint in full rotation to adjust for changing elevation of the humerus. Composite motion of the ACJ and sternoclavicular joint (SCJ) contributes up to 60 degrees of upward elevation, 15-30 degrees of posterior tipping, and 15-25 degrees of external rotation during arm elevation (measuring the motion at the ACJ is difficult and typically not done because the kinematics are not well defined). What we do know is that kinematics at the ACJ affect the "quality and quantity of movement at the scapulothoracic joint." (Neumann 2010) With motion occuring in 3 planes, the ACJ lacks stability and relies on 3 major ligaments for support. The acromioclavicular ligament and coracoclavicular ligaments (conoid and trapezoid) support the joint and resist horizontal stresses and limit superior translation respectively. These ligaments have fascial connections with nearby muscles, specifically the trapezius and deltoid. In a high grade AC joint separation, a clinician will often find these muscles injured as well. The resting position of the ACJ is the arm at the side and the closed packed position is full elevation. Due to the high prevalence of dysfunction, assessing the ACJ needs to be a priority during an initial evaluation with a patient who presents with shoulder pain.  Manual Therapy Now that we know more about the ACJ, how can we treat this joint when suspecting hypomobility? Since the ACJ is a planar joint, normal concave/ convex rules of manual therapy do not apply. Therefore, we must use our clinical judgement as to when and why to perform joint mobilization or manipulation. A major factor to consider is the patient's acuity. (The novice clinician should be aware that acute ACJ separations do not require intense manual therapy because of the acuity of their symptoms and the laxity present in the region.) Generally in more acute stages, posterior to anterior ACJ mobilizations in supine with the arm resting at the side are effective (left picture below). Remember, this is the resting position of the joint as well allowing for more mobility. As the patient's ROM and strength progresses, more intense manual therapy can be performed. For example, certain patients may only have pain and limitations at end range of motion. To reach full humeral flexion and external rotation at least 30 degrees of upward rotation and 8 degrees of external rotation is needed. (Teece 2007). An example of a more advanced manual technique is a posterior to anterior mobilization at end range using the arm as a lever. In this position, the therapist's hand blocks movement of the distal clavicle so that acromion is mobilized on the stabilized clavicle. Small oscillations of the humerus are made at the end-range promoting movement at the ACJ. There are many more mobilization and manipulative techniques and positions that can be performed at the ACJ. Hopefully this post gave you an insight into a beginner and a advanced mobilization technique. -Jim References:

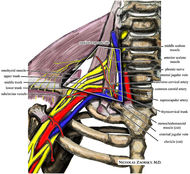

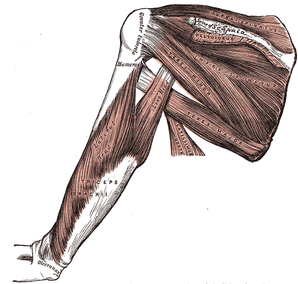

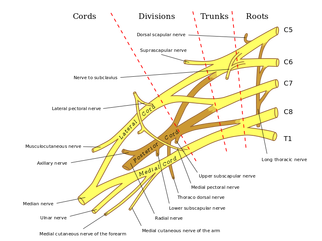

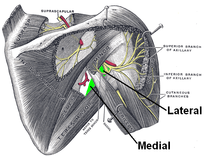

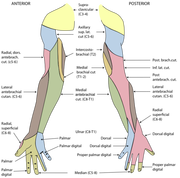

Harris, Kevin D., Gail D. Deyle, Norman W. Gill, and Robert R. Howes. "Manual Physical Therapy for Injection- Confirmed Nonacute Acromioclavicular Joint Pain." Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 42.2 (2012): 66-80. Print. Neumann, Donald A. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System: Foundations for Physical Rehabilitation. St. Louis: Mosby, 2002. N. pag. Print Teece, Rachael M., Jason B. Lunden, Angela S. Lloyd, Andrew P. Kaiser, Cort J. Cieminski, and Paula M. Ludewig. "Three-Dimensional Acromioclavicular Joint Motions During Elevation of the Arm." Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 38.4 (2008): 181-90. Print.  One of the greatest risks following an anterior shoulder dislocation is damage to the neurovascular structures which surround the glenohumeral joint. Due to their anatomical location, certain nerves are at a higher risk of injury than others following a dislocation. Additionally the position and displacement of the arm during the injury is another factor to consider. For example, "a fall with the arm in full abduction and internal rotation causes major tension on all nerves and cords." The Visser et al article also mentioned that concurrent fractures and the presence of a hematoma increasead the risk of nerve damage. Nerves that are at the greatest risk of injury include the axillary, suprascapular, and musculocataneous nerves. Throughout the literature, authors have found that the axillary nerve is most frequently and severely damaged (Visser). The axillary nerve originates from the upper trunk, posterior cord of the brachial plexus carrying nerve fibers from C5-C6. It courses around the surgical neck of the humerus before entering the quadrilateral space (see middle picture below to review the space boundaries). The nerve gives off muscular branches to the deltoid, teres minor, and long head of the triceps brachii. Due to the close association to the surgical neck, the axillary nerve is often compromised during an anterior-inferior shoulder dislocation. A study by Visser et al found that 42% of their 77 patients had axillary nerve insult following a low-velocity trauma anterior shoulder dislocation. Due to the high incidence of nerve related injuries, a complete neurovascular examination is warranted following a shoulder dislocation. This examination should include MMT of the shoulder and arm musculature, palpating for the brachial pulse, and examining sensation of the arm. When assessing for axillary nerve damage in particular, a clinician should look for muscle atrophy of the teres minor and deltoid muscles. One should suspect weak flexion, abduction, and external rotation of the shoulder. Observation and palpation would reveal a flat shoulder deformity due to deltoid atrophy. Additionally, they will have a lose of sensation over the upper lateral arm around the deltoid region due to denervation of the superior lateral cutaneous nerve of the arm (see right picture above). -Jim References:

Visser, C. P. J., L. N. J. E. M. Coene, R. Brand, and D. L. J. Tavy. "The Incidence of Nerve Injury in Anterior Dislocation of the Shoulder and Its Influence on Functional Recovery." The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 81.4 (1999): 679-85. Web.

With the common perception that the UT is often short (especially with patient reports of the muscle feeling "tight" when put on stretch - of course), it is not surprising that stretching is frequently prescribed for the muscle in patients with neck and/or shoulder pain. That's not to say it is never warranted. If the muscle length is truly assessed and found to be adaptively shortened (and non-painful), of course we want to stretch the muscle. However, we must be certain that the muscle is indeed shortened first. If the UT is truly shortened, you will find the entire shoulder heightened compared to normal, meaning both the superior angle and acromion of the scapula. Often patients are seen with an elevated superior angle but depressed acromion, suggesting a downwardly rotated scapula - components of an overactive/shortened levator scapula. An exercise commonly performed at the gym involved shoulder shrugs holding weights with the idea that the individual is strengthening the UT. However, in this position, the scapula is rotated downward and results in strengthening/reinforcing the levator scapula muscle (Sahrmann, 2002). An overactive UT is also frequently accused as the culprit in shoulder impingement. However, remember that about 1/3 of shoulder elevation is due to upward rotation of the scapula, an action of the UT. Frequently, the patient will display elevation of the scapula when trying to flex or abduct the humerus. Attention should be paid to whether or not the scapula is in upward or downward rotation with that elevation. If it appears to be downward rotation, it is essential that the UT undergoes retraining. In order to focus on the UT, the shoulders should be placed in at least 90 degrees of elevation in order to place the scapula in upward rotation and allow the shrugging aspect of the motion to come from the UT, not just the levator scapula. An additional point that should be considered is the impact on the cervical spine. Sahrmann places a strong emphasis on relative stiffness and hypermobility vs. hypomobility in her teachings. As previously discussed, the UT attaches to the cervical spine and, in doing so, can be responsible for pain at the attachment site. There are at least two possible reasons for cervical pain resulting from UT impairment. One, the UT is overactive and stronger compared to the cervical intrinsic muscles. When the muscle contracts such as during upper extremity elevation, cervical extension or rotation is frequently seen (Sahrmann, 2002). You can even feel the individual cervical vertebrae rotating during shoulder flexion/abduction. This hypermobility (a precursor to hypomobility) provides the excess stress that can lead to degeneration and, in the long run, hypomobility. In this case, the UT needs to be retrained with an emphasis placed on maintaining cervical stability and neutral cervical positioning. Two, the UT is insufficient and lengthened, resulting in a pull on the proximal attachment (cervical vertebrae) due to the weight of the scapula and upper extremity, especially during movements. These patients, too, will report that "stretching feels good." Just as the previous example, however, we must strengthen the UT in these patients, with proper positioning as explained earlier. The purpose of this post was to make us all more aware and pay specific attention to the scapulohumeral positioning both statically and dynamically in order to determine the true impairment that lies with the UT, or if there even is one at all. A starting point we like to use is assessing the medial side of the scapula at rest to determine if the resting position is upward or downward rotation. That should be followed up with a comparison of the superior angle of the scapula to the acromion as well to aid in confirmation. This positioning should then be tracked during flexion/abduction of the humerus. This is just one muscle's impact on the upper quarter, but as you can tell, it is a significant one. For more information on the topic, it is recommended you review the references listed below. References:

Kendall FP, McCreary EK, Provance PG, Rodgers MM, & Romani WA. Muscles Testing and Function with Posture and Pain. 5th edition. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005. 326. Print. Sahrmann, SA. Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 2002. 206-208. Print.  Subacromial Impingement Syndrome (SAIS) is reported to be the most frequent cause of shoulder pain in an OP physical therapy clinic. Despite the high prevalence, physical therapists still struggle to appropriately diagnose the syndrome. The gold standard for diagnosing SAIS in arthroscopic surgery. Since we do not have access to this tool everyday, we must reply on our patient examination skills. A study by Michener et al, Reliability and Diagnostic Accuracy of 5 Physical Examination Tests and Combination of Tests for Subacromial Impingement, assessed 5 special tests commonly used to help rule-in SAIS. The 5 tests were Neers, Hawkins-Kennedy, Painful Arc, Empty Can (Jobe), and External Rotation Resistance Test. Specifically this article wanted to assess the interrator reliability of the tests, diagnostic accuracy of each test, and finally if clustering the tests would confirm or rule-out SAIS. The results of the study were surprising. Moderate to Substantial strength of agreement between raters was found for the empty can test, the painful arc sign, and external rotation resistance test. Surprisingly Hawkins Kennedy had the lowest kappa value at .39. We found this surprising because Hawkins-Kennedy is graded as painful or not painful. There seems to be little room for subjectivity, yet it received the lowest reliability among raters of all the tests. The difference likely lies in how the test is performed and thus perceived. It is easy to forget to not horizontally adduct the shoulder sufficiently or to ignore the patient's compensation of elevating the tested shoulder during IR as a means of avoiding/minimizing the pain provocation. Something we must always be wary of in studies of manual techniques is accepting the fact that all examiners perform/analyze movements the same. When looking at the diagnostic accuracy of each test individually, the External rotation resistance test had the highest positive likelihood ratio (LR) of 4.39, empty can had the second highest with 3.9, and the painful arc sign came in third at positive LR 2.25. Finally, the article found that when clustering the tests a "combination of any 3 positive tests out of the 5 have the best ability to confirm SAIS, with small to moderate shifts in the pretest to posttest probability." While this article provides interesting and useful clinical information, the results are different from other studies in the literature. A separate article on SAIS by Park et al found that the clustering Hawkins-Kennedy, Infraspinatus Muscle Test, and the Painful Arc Sign yielded a high +LR (10.56) for ruling-in SAIS. So what cluster should you use? Personally, we would use both. The etiology of SAIS is multifactorial. Several structures have the potential to be pain generators and the presentation of SAIS will vary based on posture, scapulohumeral rhythm, accessory joint mechanics, and more. The Michener article was quick to point out the importance of a thorough subjective history to help aide in the diagnostic process. Reference: Michener LA, Walsworth MK, Doukas WC, Murphy KP. Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of 5 physical examination

|

| After doing some reading about regional interdependence for the SFMA inservice, we thought it would be interesting to look at some research regarding thoracic spine manipulation for shoulder pathologies, especially with the evidence for thoracic manipulations for neck pain. Regional interdependence is the idea that impairments in a separate anatomical area can contribute to the patient's primary complaint. Due to the seemingly unconventional connection between the thoracic spine and shoulder, it may appear unusual to treat shoulder pathologies with t-spine manipulations, but let's remember that limited thoracic mobility can affect the shoulder position and potentially lead to pain. There have been several studies looking at this relationship, and others. Overall, there is a decent amount of evidence displaying short-term pain relief following thoracic manipulation for shoulder pathologies, such as shoulder impingement syndrome or rotator cuff tendinopathy, even though the mechanism is poorly understood. This could potentially hasten the rehabilitation process, by allowing more aggressive therapy. |

Boyles et al performed an exploratory study on the effects of a single thoracic spine manipulation on subacromial impingement syndrome. While no additional treatment was performed, the authors were able to find statistically significant changes in both pain and disability scores in just 48 hours; however, these results were not found to be clinically significant, based on the established minimal change for clinical significance. The methods of this study were lacking in several areas: low participant number, no randomization, no control group, and more. The authors realized this and emphasized the fact that this study should be used as a launching point for further studies. The fact that significant changes were created after one treatment alone in just 48 hours suggests the potential for a component of care in dealing with patient suffering from subacromial impingement syndrome. Just as manual therapy + exercise was found to be greater than exercise alone for cervical pain, maybe the same applies to these conditions. Additionally, when using thoracic manipulations for cervical pain or lumbar manipulations for low back pain, there exists specific inclusion criteria in order to have the desired results. Again, maybe the same applies to thoracic manipulation for subacromial impingement (or other should pathologies) and we just need to discover the criteria. Sounds like a perfect research opportunity! Obviously, solid evidence on this topic is still lacking, but we hope that this research has at least opened your mind to the possibility of regional interdependence in your patients and maybe treating either the cervical or thoracic spine (or both) the next time you have a patient with a shoulder pathology.

Boyles RE, Ritland BM, Miracle BM, Barclay DM, Faul MS, Moore JH, Koppenhaver SL, Wainner RS. (2009). The short-term effects of thoracic spine thrust manipulation on patients with shoulder impingement syndrome. Man Ther. 2009 Aug;14(4):375-80. Web. 15 May 2013.

Muth S, Barbe MF, Lauer R, McClure PW. (2012). The effects of thoracic spine manipulation in subjects with signs of rotator cuff tendinopathy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012 Dec;42(12):1005-16. Web. 15 May 2013.

Strunce JB, Walker MJ, Boyles RE, Young BA. (2009). The immediate effects of thoracic spine and rib manipulation on subjects with primary complaints of shoulder pain. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17(4):230-6. Web. 15 May 2013.

Walser RF, Meserve BB, Boucher TR. (2009). The effectiveness of thoracic spine manipulation for the management of musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17(4):237-46. Web. 15 May 2013.

Dr. E outlines 5 treatment options:

1. Thoracic spine manipulation to help improve thoracic mobility and glenohumeral motion.

2. Subscapularis Release for shoulder mobility.

3. Psoas Release: He demonstrates a great new video on a new psoas technique that is much less invasive and utilizes the principles of the neurophysiological effects of muscle tone.

4. IT Band Release using the edge tool to help increase hip mobility

5. Tibial Internal Rotation Mobilization with Movement for both knee and ankle mobility. He describes how the lower leg often is put into relative external rotation due to hip weakness, medial rotation of the femur, and pronation of the foot.

He demonstrates each of these techniques with good clarity. Although he is using these techniques in relation to the overhead deep squat, you can see how they would apply to any patient with deficits in that region.

-Rotator Cuff Exercises Are Not Functional

-You Get Enough Rotator Cuff Work With Other Exercises

-If You Use Heavy Weights Your Cuff Shuts Off and Larger Muscles Take Over

-Use The Same Weight During All Rotator Cuff Exercises

Be sure to check out Mike's post to understand his reasoning behind each myth! He also has a link on the page to his previous article on myths of scapular exercises.

Insider Access pages

We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!

Archives

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

October 2016

September 2016

August 2016

July 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

March 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

November 2015

October 2015

September 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

May 2015

April 2015

March 2015

February 2015

January 2015

December 2014

November 2014

October 2014

September 2014

August 2014

July 2014

June 2014

May 2014

April 2014

March 2014

February 2014

January 2014

December 2013

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

August 2013

July 2013

June 2013

May 2013

April 2013

March 2013

February 2013

January 2013

December 2012

November 2012

October 2012

September 2012

August 2012

Categories

All

Chest

Core Muscle

Elbow

Foot

Foot And Ankle

Hip

Knee

Manual Therapy

Modalities

Motivation

Neck

Neural Tension

Other

Research

Research Article

Shoulder

Sij

Spine

Sports

Therapeutic Exercise

RSS Feed

RSS Feed