- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

Last week I was speaking with a medical doctor from Michigan who plainly stated, "I do not see why physical therapists need a doctorate degree to exercise people." It was in this moment that I could have ruined that relationship OR made it stronger. Trust me, I thought about answering it in a demeaning manner, but I didn't. I respectfully gave her an answer that changed her understanding of our profession. If you have been a physical therapist or PT student for any appreciable amount of time, you have likely encountered this question: "Why do Physical Therapists need a doctorate degree?" Answering this question can be frustrating, especially when it is being asked by a referral source. However, knowing the answer to this question is important & how you answer it can change people's viewpoint of what physical therapist's do. To answer my question above, I educated the doctor that we need our doctorate degree to ensure that the patient is appropriate for exercise. I need to make sure that my patient's shoulder pain is truly musculoskeletal pain and not cardiogenic pain. I then went on to explain that physical therapists do more than exercise. We specialize in regional interdependence, joint dysfunctions, neuromuscular disorders, and pain science. Additionally, our doctorate degree allows us to have direct access. In many states, physical therapists can now see a patient without needing a physician's referral. Several studies have shown that direct access can lower costs, expedite care, and decrease usage. A 2015 PT study out of San Antonio, Texas found that individuals immediately seen by physical therapists had lower costs and underwent fewer tests than those with a delayed referral to PT. Research is emerging on the benefits of direct access for physical therapy. When someone asks why Physical Therapists need a doctorate degree, view it as a learning opportunity. People do not understand what physical therapists do. Having a concise answer to this question is important. Teach them! Jim Like this post, check out more from TSPT or subscribe to our Insider Access Page

5 Comments

For this week's post, I'd like to pose more of a question or consideration, instead of the usual content. As many of you know, I have written about cases several times in the past about examining and treating chronic "strains." In the outpatient setting, odds are you will frequently be presented with cases where the patient reports straining a muscle months/years ago and never fully recovering. In prolonged cases like these, the connective tissue typically has healed, or at least should no longer be responsible for the pain. At this point, the nervous system is typically the culprit for any remaining pain/limitation. This can be examined and treated with any of the techniques usually utilized for the neuromuscular system. While this can readily be applied in patient presenting with chronic strains, I have recently been wondering if it is applicable to those with more acute injuries as well. With pain being a perception in the manifestation of the nervous system, should we expect there to be a significant difference in the acute setting. I'm not sure. I rarely am presented with patients complaining of an acute strain. Typically, people get hurt, then rest until it is better, or at least do some form of self-management. Occasionally, I have people come in for a free screen, where I do an assessment and provide a little treatment, along with my recommendation on how to manage the injury. I have had a few people come in with strain presentations, but show some improvement with repeated motions. Unfortunately, these clients don't typically follow-up, but there is still an improvement on display. I also often wonder how this could potentially apply to someone "risk" for a strain. If someone has a lot of neural tension limiting mobility, would a repeated motion or nerve glides decrease that risk? What are your thoughts and experiences on this? -Chris Like this post? For more advanced information, join the Insider Access Page now! Also, check out similar previous posts below:

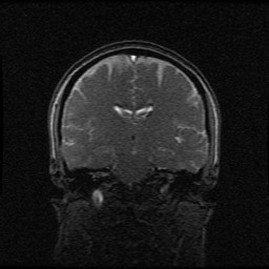

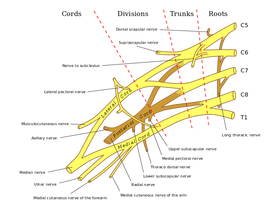

Why do so few students know the difference between residencies and fellowships? To broaden the question, why do so few students know what educational opportunities are available to them following graduation? Chris, Brian, and I often get asked "what is the difference between a residency and a fellowship program?" I am going to answer this question from an orthopedic perspective so please feel free to add your own perspective if you come from a different background. When talking with students about residency and fellowship programs, I often relate the question to the medical school model. Generally, medical students enter a residency program following medical school. A residency is a post-professional planned learned experience in a specific field of interest. For example, students interested in Orthopedics pursue Orthopedic surgery residencies. Following a medical residency, doctors have the opportunity to pursue a fellowship program. Using the example above, an Orthopedic Surgeon may choose to enter a hand surgery fellowship. Each step of learning further specializes the candidate. The process is similar for physical therapists. Following graduation, physical therapists have the opportunity to enroll in residencies. These programs are generally one year long and prepare students for their specialty certification. For example, Chris and I completed an Orthopedic Residency and were able to sit for our Orthopedic Clinical Specialty (OCS). Brian completed a Sports Residency and sat for his Sports Clinical Specialty (SCS). Other residency programs exist for the many other specialties of physical therapy- geriatrics, pediatrics, cardiopulmonary to name a few. The residency teaches you to be a clinical expert. Following residency, I chose to enter a fellowship in manual therapy. To enter a fellowship program, one must either complete a residency program, be a clinical specialist, or complete a year of pre-fellowship coursework. Pre-fellowship coursework can be obtained in several ways. (For example, Chris and I recently paired with OPTIM to start a COMT program. Our COMT program gives candidates the opportunity to pursue a manual therapy fellowship if they choose.) Fellowship training is not appropriate for new physical therapy graduates so the pre-fellowship year is a method of preparing students for fellowship training. It is the most advanced clinical certification a physical therapist can receive. I hope this helps differentiate physical therapy residencies vs. fellowships. Let me know if you have further questions! Jim Want more specific information on orthopedic topics? Check out our Insider Access Page.   A couple weeks ago I was evaluating someone with low back and groin pain. I did my usual systematic examination that included various mobility and strength measurements. I was surprised to find the patient had MMT (Manual Muscle Test) strength of 2+/5 in her gluteus maximus bilaterally. The patient was in her mid-20's, an avid rock climber, and had reported doing clamshells for strengthening regularly. The patient immediately showed a positive response to approximately 20 repetitions of repeated lumbar sideglides. While her pain wasn't 100% improved, I thought it would be interesting to reassess her gluteus maximus strength. Without doing any strengthening exercises, the patient's strength improved to 3+/5 on her MMT. This finding brings several different thoughts to mind. The most significant finding is likely just how interconnected the neuromuscular system is. We are all taught in exercise physiology classes that the first 6 weeks of strengthening exercises has a neural impact, before hypertrophy can occur. What stands out to me is just how quickly the MMT findings can change. Just as pain and mobility can quickly change in rapid responders, so can strength. What we should be asking ourselves at this point is what does the MMT actually tell us? What role do strengthening exercises play? It's very possible that the strength deficits we find in many of our patients are at least partially secondary to decreased neural input. If you remember some of our previous discussions on double crush syndrome, decreased neural flow proximally (in a potentially non-painful area) can make nerves more susceptible to injury distally. For example, a patient may lack lumbar mobility, decreasing the axoplasmic flow, which can then decrease the axoplasmic flow to certain muscle, thus appearing “weak.” This is a perfect example of why we must always check the spine systematically. The muscle might not actually be “weak!” It may just be suffering from double crush syndrome. There are several ways we can address this: manipulation/mobilization, IASTM, repeated motions, and exercise. General strengthening exercises may take the longest as it does not directly solve the “double crush” phenomena. By working on the mobility deficits, we can improve the neural input that may alter our strength measurement findings. I am not saying there isn't a role for strengthening exercises. There are definitely examples of true strength deficits that require strengthening exercises. Even in rapid responders, they can play a role. Think of it similar to IASTM. We are stimulating the affected nerves peripherally which can improve the neural input. The strengthening exercises can also work to truly improve strength. The best approach is likely an eclectic approach. -Chris Like this post? For more advanced information, join the Insider Access Page now! Also, check out similar previous posts below:

The Student Physical Therapist recently partnered with OPTIM Physical Therapy for the Murph Challenge. "The Murph Challenge is the Official Forged® annual fundraiser, benefiting the LT. Michael P. Murphy Memorial Scholarship Foundation. This is a CALL TO ACTION - Rise to the occasion. Take the Challenge. Help make 2015 the biggest year yet!" Let’s Move Forward as a profession by taking the Murph Challenge. Register under OPTIM Physical Therapists so we can support the challenge as a profession. Let's see how many physical therapists we can get to support this great cause! Check out OPTIM's website to learn how to register for the challenge. The most important thing I have learned since finishing physical therapy school is that we always must act with purpose. What I mean by this is that as a health care professional it is my duty to treat my patients with the highest quality and integrity. Part of what that includes is making sure I do the very best I can for my patients. With the abundance of changes in the physical therapy world it is important to me to reflect on how my patient's are doing each week. Every week I spend a few hours reviewing what went on with my patients and how my treatment plan needs to evolve in the upcoming weeks. What I have learned from this over the past few years is that this process has become a integral part to my growth as a physical therapist. Some weeks I spend more time on communication and others I spend more time on different exercises or manual therapy interventions. It would be very easy to just sit back every week and not update or think about the small changes week to week with treatment plans. But I believe it is very important to spend some time reflecting each week to not only improve as a heath care professional but to give the highest quality of care to our patients. Below are the 5 questi ons I ask myself each week. 1. What did I do well with this week? 2. What did I do poorly with this week? 3. Are my patient's on track to where I anticipated they would be after the initial evaluation and treatment plan? 4. Who or what needs to be updated/changed? 5. What knowledge or skill do I need to improve for this certain patient? Try to reflect each week on your patients and yourself. You will benefit greatly. - Brian Enjoy this post? Check out others from the student physical therapist website! OR join our insider access page! uSC Sports Residency reflectionPhysical therapy schools do a great job teaching students the fundamentals of physical therapy. Students learn a wide variety of topics leaving them with knowledge spread across many different specialty areas. This is both good and bad, We are trained to be general practitioners. Being a general practitioner means you can practice in any setting with a baseline level of competence. Since the human body is so complex (and our knowledge of the brain and central nervous system is continually evolving), physical therapy school does not have opportunity to teach us to be a specialist. There is simply not enough time in 3 years. The purpose of this post is not to discuss the downsides of physical therapy school, but to discuss the need to continue developing our skill sets after physical therapy school. What is the best way to specialize in your area of interest? After PT school, Chris, Brian, and I all attended orthopedic residency programs. These programs were intense 1-year programs teaching us to be experts in neuromuscular diagnosis, examination, and treatment. Key concepts of my program were pain science, exercise prescription, manual and manipulative therapy, and intervention selection. Since the residency program was my full time job, I could finally spend 100% of my attention on neuromuscular and orthopedic concepts. Prior to the residency, these orthopedic topics were simply wrote memorization put into practice. A residency or fellowship program may not be for everyone. Residencies cost a considerable amount of time and money. Fortunately, you can still train to be an expert without attending a residency. Today there are many other advanced programs to choose from. Online learning opportunities are now giving students higher level learning experiences. Medbridge is a great example of this. Other programs offer continuing development using online didactice learning and in person lab sessions over the course of 1 or 2 years. Whatever your interest, I highly recommend finding yourself an advanced learning program. If you are failing to prepare yourself for the future, you are preparing to fail. Get out and specialize. Jim Enjoy this post? Check out others from the student physical therapist website! OR join our insider access page!

Having recently completed reading Therapeutic Neuroscience Education, I have started to realize just how powerful the mind can be with our patients. With the development of modern pain science, this may indicate a need to increase our scrutiny when assessing the validity and quality of research as it becomes published. The old biomechanical model, while still relevant, is not the leading foundation we once thought it was. For those of you not familiar with some of the recent developments in pain research, we’ll do a little review. All pain comes from the brain. No matter what the “injury” is, the pain is coming from the brain. When a threat is detected in the body, signals are sent to the brain. Depending on the level of importance, you may or may not perceive pain. This is important to recognize, because of everything that is happening in and controlled by the brain. Emotions, bodily functions, respiratory rate, control of blood flow, muscle contraction, etc., it all is controlled by the brain. This is important to understand, because the functions of one area can influence another. For example, have you ever noticed a patient’s pain was worse when they are having a bad day or depressed? The emotional aspects of the brain, when stimulated in certain ways, can make it easier for your patient to “feel pain,” simply from raising the threat level. Couple that with the lack of correlation between imaging findings and pain. Things like herniated discs, meniscal tears, bone spurs, spinal stenosis, osteoarthritis, RTC tears, etc. are just normal wear and tear. These are found in many asymptomatic individuals. Another example includes the biopsychosocial approach. I’m sure you’ve had patients who claim “the one thing that works for me is ultrasound.” What much of the research has shown is that there is rarely any benefit to including ultrasound in treatment. But in those patients who swear by it, you may notice an improvement in their symptoms. How could this be? Is it possible the patient was convinced that they would get better, so the brain allowed the threat level to be lowered? I bring this up because of the impact a placebo can have. Studies have shown no difference between sham US and therapeutic US. No difference has been found between partial meniscectomy and sham surgery. No patient subjective reports were significantly different between those who had a successful RTC repair and those who had a re-tear. With our understanding of modern pain science, there are several ways we can interpret in these findings. One is the possibility again for the mind’s contribution. It’s possible that with the various sham treatments that because the patient thought they were getting treated, they actually felt better. Building off of this, is a placebo the same as no treatment? It doesn’t appear so. A patient’s beliefs can have significant impact on the results of an intervention, which is why it is imperative that we consider our patient’s preference in our treatment plan. This can lead us down a path with potentially difficult decisions to make. Even though the biomechanical approach is not as significant as we once thought, should we revert back to that model in patients that are fixated on the theory? If we were to jump to an explanation of pain science right away, the patient may shut down completely to any further treatment consideration. With the impact we know the mind can have, this would be one of the worst things we could do as the patient would not even allow themselves to get better. Likely there is a middle ground to be found. A slow introduction of pain science, while touching on the patient’s existing beliefs, may help to build the trust needed to allow healing to occur. This should be considered in both the clinical and research article appraisals. -Chris References:

Like this post? For more advanced information, join the Insider Access Page now! Also, check out similar previous posts below:

The quality of lumbar spine movement and a patient's willingness to load through their spine is key to any lower body functional movement- squat, single leg balance, running, or even sit to stand. An inability to load through the spine alters the joint mechanics above and below the spine. In these instances other joints must change their role to compensate for altered lumbar mechanics. For this reason it is important assess lumbar spine cardinal plane range of motion with every lumbar and lower quarter evaluation (hip, knee, and ankle). When I say 'assess range of motion,' I do not mean using a goniometer or inclinometer to check their degree of movement. I am looking to see if a patient has functional or dysfunctional motion. For example, when a patient flexes forward, do they own that movement. Is it painful? Do they have a uniform spinal curve? Can they touch their toes? Where does the motion come from- thoracic, lumbar, hips, or combined? When assessing lumbar spine AROM, it is essential to focus on the following components: 1) Order of the movements- If the patient is not acute, I prefer to assess flexion, then extension, then sideglides (sidebending), and finally rotation. If they are acute, check least painful to most painful. 2) Loss of movement- Do they have full range of motion? Early on it is acceptable to use a measuring device, but in reality, the answer is much more objective. Yes or No? 3) Pain or stiffness present during the movement- Be sure to ask when the pain arises and where the pain is located. 4) Aberrant movements- These include shaking, catching, or uncoordinated muscle contractions. Clinically look to see if the patient has to use his hands to press up from a flexed position. Do they move in one plane or 'wiggle' their way into the movement. In rotation, do they flex or extend as they rotate? 5) Ownership of the movement. This means reaching full range in a fluid, stress free manner. Clinically look to see if the patient confidently moves through the entire range. Assess if they have to use momentum to reach full range of motion. 6) Uniform spinal curve. With lumbar flexion, does the patient have reversal of their lumbar curve? With extension, is the patient hinging excessively from one level? The above is my check system when assessing lumbar range of motion. Do you do anything different? Would you add anything? -Jim Heafner

Enjoy this post? Check out more from TSPT or join our INSIDER ACCESS page for exclusive material!  Okay, so this post doesn't have much to do with evaluation or treatments in the clinic. Instead, I want to talk to you about why you must network. This is probably a topic you don't often put much thought into but you should. Having a good network of people can be a career changer. Here's why.... 1. Networking can get you more clients. It's true and quite easy. Take just one doctor for example. Lets say you get a direct access patient who needs to be referred out. You could easily just send a note to the doctor and send the patient on in. The problem with that scenario is that you just lost a potential referral source. Instead, try going to the patient's MD appointment. Introduce yourself and have good working knowledge on both the patient's condition and the doctor's background. I promise you, if you make the doctor's day easier, he/she will be happy. Following up can turn into a good relationship for you and a doctor. 2. Networking can boost your name. How do the best in there respective fields get consistent (and sometimes famous) patients? Well, sometimes they are just that good. But sometimes, they are just a good talker. My advice is master both. Become very good at your craft and also learn how to sell. I'm not talking about being a salesman, but instead showing a patient how much better they have become and how passionate you are. This is where having a good asterisk sign during treatments can be effective and shows patient's constant improvements. Furthermore, when patient's bring up other friends or family members that have been injured, simply ask them if you can be of service. Soon you will be bringing in a new patient for every one you discharge and thereby building your name/brand. 3. Networking can be lucrative. The more you talk with your patients and potential referrals the more likely you will have a chance at earning more money. How you say? Well, there is corporate wellness, speaking engagements, teaching, etc. Someone somewhere is looking for a physical therapist to speak to their fitness class or corporate wellness group. Always be open to other endeavors outside of the clinic. - Brian Like this post? For more advance information, join the Insider Access Page!, Also, check out similar previous posts below |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed