- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

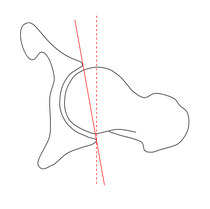

A frequent patient type that comes into my clinic is the senior golfer. Golf is an incredible sport that many are fortunate to play throughout the majority of their lift. While there is little impact in the game, the repetitive motion often is associated with hip or low back pain. While we do not advocate the idea of assessing and treating pathoanatomically, we do believe that motion is good for the human body. Golf is a sport that requires movement in at many joints throughout the body, and a restriction in one area may impact another. A site of common dysfunctional motion in the senior population is the hip. With the propensity of low back pain in senior golfer patients, we must be sure to improve mobility both locally and far from the affected area. A frequent presentation of hip arthritis (even non-painful arthritis) is loss of hip IR ROM. With golf requiring rotation in both directions, each hip is required to move into both IR and ER at different parts of the swing. A loss of hip IR leads to increased strain in another part of the body during the swing (possibly the lumbar spine). While we can try and improve hip mobility into the restriction, we may have limited success. A potential fix for these patients is to adjust the hip position at the initial swing. For patients with loss of hip IR mobility (either with significant hip OA or retroversion), we can externally rotated the lower extremities slightly bilaterally before the swing begins. That way the hip can move into relative internal and external rotation throughout the swing.

Again, I cannot stress enough the importance of not automatically having your patients switch to this positioning. You patient may respond to some form of manual treatment, exercise, or other intervention to improve hip mobility; however, should they fail to respond, adapting the hips to an externally rotated position can permit some relative internal rotation mobility. We look for anyway we can help our patients reach their goals. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

1 Comment

One of the core concepts of kinesiology, a foundation of physical therapy, is understanding lever systems. A lever system is described when using muscles to move joints as the relation between 3 components: load, fulcrum, and effort. There are 3 ways that these components are organized in order to create force and move a load. This should serve as a good review for anyone studying kinesiology or to better understand how our muscles are affecting our joints.

Hopefully this will serve as a good review for some of you in school or in the clinic. Often these foundational concepts are overlooked, but can play a role in standard rehabilitation programs. Not only does it help us in knowing how to properly load each joint/muscle, but it also can tell us what those muscles are to do. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

I've written before about the benefits of being thorough with our examination to the point of not missing any contributing factor, but the same principle also applies to our treatments. Having proper technique with each examination method is essential in order to know the true results. A poorly performed Lachman's test can easily make a torn ACL appear intact, while a properly performed test is highly sensitive and specific. If a testing measure is not performed exactly how it should be, there is basically no point in actually using it. In regards to how the principle applies to treatments, we should consider how a small variation makes an enormous difference. For example, when performing resisted clamshells, if the patient is getting the rotational motion from the spine, the gluteus muscles are no longer being targeted. If the proper load isn't applied, the exercise isn't even having a strengthening effect. This goes for other treatments as well: repeated motions, manual therapy, and more. I'm not saying that there is a perfect way to perform specific manual treatment techniques or other exercises, but there are things that can be done to significantly decrease their effectiveness. Our job should be to increase the likelihood of each intervention. It is frustrating for me to hear that a patient failed to have success with physical therapy or a specific intervention and then have the patient say they think it is pointless to pursue it. With how frequently we see inconsistency in exercise prescription, examination and treatment techniques, and overall philosophy of practice, we shouldn't assume that just because a patient didn't respond to a treatment previously, they won't respond in the future. I can't tell you how many times I've had co-workers or students say a patient didn't respond to repeated motions, and then I take a look at the patient and with a couple of adjustments the patient has a positive response. We shouldn't be so quick to say a patient is a non-responder, especially with the inconsistencies out there. I recommend reassessing your asterisk sign after each intervention and avoid negative reinforcement about our interventions with our patients. With the benefits of placebo and pain science research, we often can hurt ourselves and our plan of care by telling our patients they for sure won't respond to a specific intervention. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

One treatment technique that physical therapists are most known for is exercise. There are many, many different exercises out there, and we are limited only by our own creativity. Unfortunately, is is far too easy for us to fall into the habit of prescribing an exercise based on diagnosis or what we think are patterns of presentation. In reality, our exercise prescription should only be based on impairment and potential co-morbidities and biopsychosocial factors. The most obvious component to consider is the impairment. We typically give an exercise to address deficits in strength, mobility, motor control or the cardiovascular system. If a muscle is weak, we try to strengthen it. If a straight leg raise is limited by neural tension, muscle flexibility, etc., we address it. If there is a potential abnormal movement pattern, we may try to fix it. As far as the CV system goes, this often has to be challenged in patients with chronic pain in particular, but applies to many different types of injuries. Included in these, of course, is proper dosage. Far too much do I see patients performing the majority of their exercises on the table. While plenty can be done to progress a patient there, we must be certain we are appropriately challenging them. Almost no one functions completely supine, so getting to the upright and dynamic position is critical. Also, we shouldn't just blindly give an exercises 3 reps of 10. An exercise targeting strength-building should be about 6 repetitions where the weight is so heavy that another repetition is not possible. Rest between sets plays a role as well for which metabolic system is being challenged. Make certain your dosage addresses what you want (strength, tissue loading, whatever). I often say to my patients if they aren't sweating, I'm not doing my job. Addressing the impairment is actually the easy part. Making sure you consider the impact of any co-morbidities or any biopsychosocial factors is probably more important, but definitely more difficult, in my opinion. A patient s/p TKA may be ready to move off the table, but their history of a neurological issue impairing their balance may make you concerned. This is where you have to get creative in progressing your patient, while ensuring the appropriate precautions. Regarding the biopsychosocial factors, fear-avoidant behavior is one of many things we will encounter. There are plenty of patients that have a mental component that needs to be addressed in order to help them improve their function. While a big focus should definitely be on pain science, that isn't wear it stops. Sometimes we have to introduce motion in a less threatening manner in build from there. Sometimes we have to work out the cardiovascular system as discussed previously. These are essential for consideration as simply addressing the impairment doesn't always work. Exercise selection is fundamental for physical therapists and should have quite a bit of thought go into the process. I challenge you to assess what each exercise is supposed to be doing and is it actually doing it with each patient you see tomorrow. Odds are you will start to makes some change and then notice your patients making changes as well. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

|

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed