- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

|

When setting up a patient's schedule after doing an evaluation, there is typically a preference from both the therapist and patients for continuity. But in a modern physical therapy clinic, it is difficult and rare to meet this demand. Many patients either want to come in before or after work, leading to a backlog of patient requests for those time slots. With working in a clinic with multiple therapists, patients often end up having several treatment sessions with other therapists. This can be frustrating for several reasons. When evaluating a patient, we set up a plan of care on paper and in our minds for how to manage that patient's condition. Maybe we have particular manual therapy techniques or exercises we want performed in particular sessions. It's possible, and likely, that other therapists may not know what you are looking for with specific exercises or even how to perform certain manual techniques. When treating someone else's patient, we become hesitant to adjust any treatments the patient might receive out of fear of altering the main therapist's plan of care, having the patient lose faith in the main therapist, or at worst possibly regress a patient! That being said, there are definitely benefits to having multiple therapists treat a patient occasionally. As thorough as we like to think we are with our evaluations, it is not impossible for there to be something that we missed. Whether we just weren't thorough enough with our assessment or we lack the experience and skill to pick up an essential impairment, a second set of eyes can be extremely beneficial. That ties right in to the benefit of various backgrounds for treatment. Perhaps you are aware of a treatment method that would be extremely useful for a patient, but you don't actually know how to do it. With all the continuing education courses available and various schools for physical therapy, it is possible that other clinicians in your setting may have those skills. I am fortunate to work in a clinic with 3 other therapists, all with different backgrounds. I have already been utilizing their unique skill-set in my 2 months of working there. So which is better? As in most cases, a little bit of both can be preferable. Personally, I think a consistent relationship between one physical therapist and one patient is the better option and cannot be underestimated. The trust developed between the PT and the patient may alone enhance the patient's experience. It is also far easier to maintain the original plan of care that was set in place. However, when we do notice lack of progress in our patients and run out of answers, it is definitely beneficial having another physical therapist work on and assess the patient. In the end, patient outcomes are what is most important, and we likely will not always have the answer. That second set of eyes may be just what is necessary to reach the remaining goals.

-Chris

1 Comment

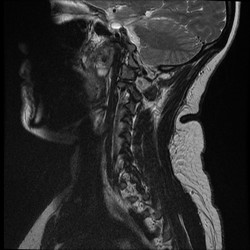

In school, many students are taught about the clinical significance of imaging, but how many end up utilizing it clinically? It seems like I rarely go a day when I don't hear a patient or clinician mention how bad the patients' MRI findings are and how that is the reason for the patient's symptoms. "So and so blew out a disc lifting a heavy box," "I have 3 slipped discs in my neck," or "the MRI revealed impingement at C4." The list goes on and on; however, my personal favorite is "my knees are bone on bone!" Sure the MRI can pick these things up, but do they matter? While I support the use of imaging to help rule out various non-musculoskeletal pathologies and life-threatening symptoms, there is quite a bit of evidence that says we should not rely on imaging for things like determining the significance of herniate discs, stenosis, bone spurs, and more (Boden et al, 1990 & Jensen et al, 1994). What these studies reveal is that quite a few people without any symptoms or complaints have the same MRI findings as those with pain. What does this mean? While it is theoretically possible that findings like stenosis, bone spurs, and discs can create various symptoms, just because we see something on an MRI does not mean that it is the source of our patient's symptoms. This is why I get frustrated when I hear patients (or PT's) start to list off their findings or when patients and health care practitioners are pushing for surgery. As clinicians, we should regularly educate our patients on just how insignificant some imaging results can be in regard to orthopaedic complaints. What we have discussed thus far does not even touch upon our understanding of modern pain science. Having recently completed Butler and Moseley's Explain Pain, my understanding of what "pain" actually means and how it develops has changed drastically. We don't actually have pain receptors. We have an intricate system of "danger" (noci-) receptors. This system is influenced by different cultural upbringings, our surroundings, and much more. It can even adapt to affect and be affect by other parts of the nervous system! What we feels as pain often occurs for a reason, to warn us. However, the nervous system can become hypersensitive and lead to various types of chronic pain. Think about diagnoses such as Chronic Regional Pain Syndrome. These patients actually visualize the affected body part as being enlarged! How is it that someone with horrendous pain from a "blown disc" can immediately get near 100% within a couple days with something like repeated motions? We aren't pushing the disc back into place; we are affecting the nervous system! This ties right back in with abnormal imaging findings. We cannot let the results of an MRI impact our clinical decisions and treatments based on this. I am not advocating against the use of MRI's (or other types) in general, but I believe we do a disservice to our patients by biasing their mind with MRI results before even giving therapy a shot. This thought process alone can affect how the patient perceives their disability and affects the function of the nervous system. With the right treatment technique (repeated motions, manual therapy, chronic pain education), most patients should see improvement. -Chris Reference:

Boden SD1, Davis DO, Dina TS, Patronas NJ, Wiesel SW. (1990). Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990 Mar;72(3):403-8. Web. 24 Aug 2014. Butler D & Moseley L. (2013). Explain Pain: 2nd Edition. NOI Group. 2013 Sept. Print. Jensen MC1, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian D, Ross JS. (1994). Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994 Jul 14;331(2):69-73. Web. 24 Aug 2014.  A few weeks ago, I read an article about the need for developing a system for assessing hip rotation ROM in weight-bearing compared to our standard NWB positions. While it is great that researchers are becoming aware of the differences between anatomical ROM and functional ROM, the study has a somewhat limited focus on female golfers. In reality, the importance of these differences apply to all patients, not just athletes. As we have stated in previous posts, we strongly encourage the type of systematic assessment for mobility that is included in the Selective Functional Movement Assessment (SFMA). The beauty of the evaluation method is that it takes the patient through various levels of required motor control for each combined or single movement. This is an essential concept as it can get to the root of the problem. With our standing tests of combined patterns, mobility, motor control/stability, and postural control are all required. If a dysfunctional movement pattern is found, the patient then is taken into a NWB (or less WB) position, where the test may be performed again. You may be surprised to find your patient's pattern is now fully functional! Should the pattern still be dysfunctional, each pattern can be broken down and tested actively versus passively to determine if mobility or stability/motor control is the primary concern. Whether you use the SFMA system or another method, assessing movement with various levels of stability is something we should consider with all our patients. Without adequate examination, we may be mistreating the impairments of our patients. Why stretch a hamstring in someone that can't touch their toes if they have 80 degrees of active SLR? By breaking down each level of stability, we can better determine the true source of the patient's limitations. -Chris A few weeks back Chris wrote a great post on Sequencing Your Treatment Session. His post focused heavily on manual treatment and the importance of checking and rechecking your asterisk (concordant) sign. This post is intended to be a quick and dirty outline regarding how to prioritize interventions from start to finish. Not all apply to every patient, but knowing the sequence is fundamental.

1) Brief Subjective/Objective Recheck: This should be viewed as a mini-reassessment. Was there any change in symptoms since their last visit? How did they tolerate the their HEP? How did the patient respond 24-hours after the last treatment? Objectively, are the same restrictions and movement impairments present? 2) Manual Therapy: During the objective, you likely found a joint restriction or movement pattern that needs correcting. Perform the necessary manual techniques and re-check your asterisk sign. 3) Corrective Exercise: Performing corrective exercises immediately following manual therapy will maximize the patient's ability to find and recruit muscles that were previously not recruiting normally. 4) Functional Warm-up: The warm-up should increase core temperature targeting the muscle groups that are dysfunctional. Examples: bicycle, total gym, elliptical. 5) Power Exercises: Incorporate power/ plyometric exercises following the warm-up when the muscles are not fatigued. Since form is essential during these exercises, performing them while the muscles are fresh is very important. It should be noted that not all patients will be ready for power-type exercises during their first few visits. 6) Strength Exercises: Strength exercises include those performed in the 4-8 repetition range, 3-4 sets with 2-3 minutes of rest between each set. Similar to power, not all patients can tolerate pure strengthening early on. Many times patients require a few sessions of neuromuscular re-education and form re-training prior to pure strengthening. 7) Conditioning and Endurance: Often we find ourselves going directly to this stage following a functional warm-up. Since pain and movement impairments our the primary focus early on, performing conditioning or retraining exercises is acceptable. The dosage of these exercises is typically 3 sets of >10 repetitions with less rest in between sets. A main focus is on proper form and controlling the movement throughout the ROM. 8) Warm Down Appropriately structuring a treatment session is a key component to the patient's success. One question you need to continually ask yourself: "how do you dose pain?" There is no perfect answer. Pain generally leads to muscle inhibition and form breakdown which often categorizes the patient in the conditioning and retraining exercises section. As your patient progresses it is essential to perform the exercises in an appropriate order to maintain form and maximize gains throughout the session. -Jim  A couple months ago, we were sent some samples of orthopaedic texts to review. Having come from a program where no real orthopaedic text books were issued, we were very interested in the opportunity to see what Prohealth had to offer. Given our backgrounds now as residency-trained therapists, we also can add some additional perspective on what is essential for orthopaedic texts. The books included in our review are: Muscle Manual, Spinal Manual, Extremity Manual, Orthopaedic Conditions, Physical Medicine, and Physical Assessment. The Muscle Manual is an equivalent of what the famous Florence Kendall presented in her texts. However, the Muscle Manual offers much more than Kendall in other areas. Not only does this book include origin, insertion, action, innervation, blood supply, muscle strength test, or muscle length test, the book also offers anatomic variations, common injuries, palpation technique, trigger point referral, methods to strengthen and stretch the muscle. These additions have pretty significant clinical implications. Now with all that being said, in our opinion the book is lacking in detail of the muscle attachment sites. The importance of this is debatable as with all the anatomical variations, the need for exact specifications for each muscle (i.e. "the anterolateral surface of the proximal portion...") may be less significant. The next couple books go hand in hand: Spinal Manual and Extremity Manual. These probably compare with most of the orthopaedic text books on the market that schools are aware of. Each book is divided into joint-based sections (i.e. cervical spine, shoulder, etc). At the beginning of each sections, there is a review of anatomy, kinesiology, ROM, MMT and exam flow for the joint. The section then leads into a breakdown of each common pathology for the joint. These breakdowns include: basic information, classification, demographics, history, physical exam findings, a multi-disciplinary treatment approach, and prognosis. This can be beneficial considering how often we are asked about different treatment approaches for each pathology (acupuncture, medications, diet and botanicals, etc. As we move towards a more connected health care system, this will be essential in providing our patients the best care. The books also contain an opening that includes a breakdown of how subjective histories should be taken, how to analyze articles, systems review, differential diagnosis, gait cycle, and more. These inclusive text books can be extremely beneficial for those trying to figure out proper exam flow and may be good references for the boards or OCS exam. Unfortunately, these texts are lacking in movement analysis. Like most orthopaedic text books, a pathological approach is taken that primarily involves treating the symptomatic tissues, not the cause of the symptomatic tissue. Leaving out subjects like Sahrmann's movement impairment syndromes or other methods of movement analysis prevents many from treating the original cause of the problem. However, these texts would still stand as excellent references for a condition and possibly various evidence-based treatment approaches. Prohealth also offers an Orthopedic Conditions text which is packed with useful information regarding assessment, diagnosis, and management of Orthopedic conditions. Under each diagnosis section, information is included on history, physical exam, differential diagnosis, special tests, diagnostic imaging, and laboratory tests. Having the imaging and laboratory tests included in the diagnosis is extremely helpful. For example, when reading about the scaphoid fracture, Dr. Vizniak includes an X-ray, T1 MRI, and T2 MRI images to show the differences between each image. At the end of the book, he includes a Key Movement Patterns (KMP) section outlining common movement patterns that occur in response to poor posture or pain. It is not as in depth as a Sahrmann type movement impairment syndromes, but it is a great quick guide to assessing for movement dysfunction. We can honestly say that the Orthopedic Conditions book is an excellent evidenced informed guide to helping manage musculoskeletal conditions. For more specific treatment techniques, the Physical Medicine text may prove useful. The book includes a joint-by-joint breakdown of various treatments and assessments. Methods of mobilization, manipulation, MET's, STM, strengthening and stretching are included for each joint. Additionally, taping, electrotherapy, acupuncture, and nutrition are covered. This may prove useful as a reference for those looking for a taping technique, a suggestion for herbal supplements, different manual techniques and more. While no substitute can be made for actual practice and learning with the instructor of manual techniques, this book allows one to review the various methods of treatment and assessment with ease. The Physical Assessment book is useful for various examination techniques and special tests. It includes images, descriptions and diagnostic accuracy for the tests.

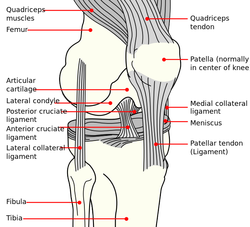

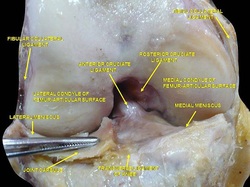

While these texts may not represent the movement towards a kinesiopathology approach for physical therapy, they definitely play a role as references for the clinic for specific pathologies, assessment, treatment, and anatomy in general. The global approach each text provides in developing the clinical reasoning of the reader can be an incredible component to the growth of a professional. Additionally, each book has links to videos on the website that provides an alternative learning method and supplementary information. Check out on the website for more information for these books. My Conservative Management of a Medial Collateral Ligament Ligament Injury: Advice and More6/13/2014  This post was inspired by a personal injury I sustained ~6 weeks ago. The nature of the injury will remain disclosed as it was a rather embarrassing traumatic event. Regardless clinical tests and measures ruled in a low/medium grade Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL) injury. With the help of some colleagues and personal knowledge, I have been self treating the injury and want to give some personal feedback regarding the process. Below are 5 key points I will touch on from a patient perspective: 1. The acute pain is real- it must treated before we can address other impairments. It is most important during the acute stage that the clinician rule-out complete ligament rupture and/or neurovascular damage prior to addressing other impairments. For 3-5 days following the injury, I would experience sharp pains with knee flexion and extension. During this time period, all provocation clinical tests were positive: McMurray, Valgus Stress Test, Apley's Compression and Distraction. Performing rotational movements such as getting out of the driver's seat of my car seemed impossible. This movement is essentially performing a self Thessaly Test. So why were all tests and measures positive? Following a knee injury, pain and swelling surround the knee make all movement painful. Swelling moves to the path of least resistance, which is located inside the joint. Additionally, it is important to look at the anatomy. The MCL has attachments into the medial meniscus, posterior-medial joint capsule, and semimembranosis tendon. The proximity of these structures can cause significant shearing to the entire area which confounds the results of the physical examination. Managing the acute pain quickly and effectively is extremely important to progressing the rehabilitation. 2. Restoring the normal joint kinematics, ROM, and muscle function is key. Following a knee injury several key impairments exist that need to be managed early in the rehabilitation process. As I stated above, addressing the acute symptoms of swelling and pain are necessary. Significant flexion and extension ROM deficits will exist and quad lag will be present. Management of these symptoms is basic, but the importance can not be understated. Since the injury, I have been much more adamant with my patients about performing heel slides, quad sets, short arc quads, and allowing me to perform tibiofemoral mobilization and manipulation. Before the injury I discredited the importance of such simple movements. One exercise I often prescribe is a heel slide + quad set combo to get a quadriceps contraction, allow for the screw home mechanism to work, and also reach full flexion in the same exercise. These exercises are relatively boring and simple, but boring does not mean unimportant and that message needs to be translated to your patients. Restoring these basic impairments- ROM, quadriceps strength, and accessory mobility- must occur before higher level strengthening and dynamic movements are brought into therapy. 3. Performing the home exercise program is not enjoyable, but it is necessary. As stated above, the early HEP is not fun and often temporarily causes increased discomfort (similar to pain) and swelling following excess movement. Anatomically speaking, discomfort is expected. Throughout knee ROM different portions of the MCL become taut. In full extension, the posterior fibers are taut and during flexion, the anterior fibers become taut. We are stressing the disrupted tissue during our HEP, but it is gentle stress which helps restore normal tensile forces to the ligament. Think about the effects of Exercise and Tissue Healing. For the first few weeks I would joke that it felt as if I had knee arthritis. The knee was very stiff in the morning with initial weight bearing and loosened within the first few steps. The pain and stiffness was related to residual swelling stuck in the knee. Personally I neglected flexion range of motion early because of the discomfort I felt during the movement. Now I am still feeling the effects of not reaching this range earlier during the rehab. The HEP needs to be performed early and often.  4. Do not do too much too soon. Within 3 weeks following the injury, I had "acceptable" ROM and almost full quadriceps strength and good hip strength. I had been biking for 75+ minutes at a time and was mentally exhausted from having a knee injury. I wanted to return to my prior level so I did- or at least tried to. At week 3 I returned to performing light weighted squats, running short distances, burpees, and more. This was unsuccessful. "Acceptable" ROM and almost full quad strength will not work. My body was compensating for these impairments by using the other limb greater and substituting where ever possible. I was having muscle soreness and aches in my other hip and low back. Despite these aches, I continued to load the joint abnormally, hoping the discomfort would subside. After 1-2 weeks of this exercise, my knee was just as stiff and now noticing a clicking with end-range flexion. Naturally, I was thinking an added mensical injury- pain with flexion OP, pain with extension OP, joint line tenderness, positive McMurray, and clicking and popping into flexion. Fortunately, I did not have any joint locking. I need an X-ray or MRI right? Not so fast. After resuming my prior HEP and receiving some advanced manual techniques in clinic, all of my symptoms except pain with flexion overpressure have diminished. Before jumping to any conclusions regarding imaging or surgical options, allow yourself to restore the normal joint mechanics and see what happens. I may have a partially torn meniscus, but am I a surgical candidate? What would imaging show me that would change my plan of care at this point? When working with your patients, respect the tissue healing process and use the exercise progressions and available return to sport criteria before letting them jump into full activity. 5. There will be Ups and Downs during the rehab process. I am now six weeks into my rehabilitation and things are going well. Things have not always gone well though. I became frustrated several times during the process which has slowed down my return to activity. Do not test the gods of tissue healing because they will win. The body has a natural process it must go through following injury. Final words of advice: start simple, restore normal anatomy, and use clinical judgment and any available tools for exercise progression. -Jim  General Overview Time and time again, the Occupational Therapists in my clinic get referrals for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS). In some of these cases, the patients also have cervical pain, shoulder pain, proximal forearm weakness, and/or palmar paresthesias. While these individuals may have compression within the carpal tunnel, many of them are suffering from nerve entrapment proximal to the carpal tunnel. Many develop adverse neural tension caused by postural dysfunctions, muscle imbalances, and systemic comorbidities which cause a breakdown of the nervous system. Am I saying CTS is over-diagnosed? That is exactly what I am saying. It has become a blanket term for pain in the wrist and hand just as lateral epicondylagia has at the elbow. Many times, the cause of someone's symptoms is not consistent with the referring diagnosis. In this mini-review, I will break down a few areas of entrapment of the median nerve and how to assess for adverse neural tension within the median nerve. Median Nerve Pathway The median nerve is formed from contributions of the spinal nerve roots C5-T1. After originating from the brachial plexus in the axilla, the medial nerve travels down the arm to the cubital fossa. Next, the nerve travels through the two heads of the pronator teres and between the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus muscles. At this point the median nerve splits into the anterior interosseous nerve (AIN) and palmar cutaneous nerve. Finally, the nerve travels through the carpal tunnel space. (Be aware there are many alternative anatomy presentations; this is simply one of the most common ones). As you can see there are many points of entrapment for the median nerve: the cervical spine, interscalene musculature, between the heads of the pronator teres, and within the carpal tunnel (among other less common ones). The patient's subjective reports and your clinical examination will point you to the correct structure and location of dysfunction. When suspecting neural tension, a clinical examination measure you should utilize is the Median Nerve ULTT. Assessing for Adverse Neural Tension & Different Sites of Entrapment We have discussed adverse neural tension several times before on The Student Physical Therapist (How to assess neural tension, Differential Dx in neural tension). At the Harris Health Orthopedic Residency, I use 3 distinguishing criteria for positive adverse neural tension testing. The symptom(s) must reproduce the patient's primary complaint, it must change by moving a component at a joint proximal or distal to the complaint, and it must be different side to side. To see the full test for adverse neural tension of the median nerve, click HERE. This test will not tell you the exact location of symptoms, but it will give you an understanding of the sensitivity of the nerve. In addition to performing neural tensioning tests, it is important to perform a thorough assessment of other potential areas of entrapment. For example, if you find muscle wasting in the FPL, pronator quadratus, and/or radial half of the FDP, the involved nerve is likely the AIN being compressed in the proximal forearm. Additionally, if the patient has comorbidities that affect the nervous system, such as a history of uncontrolled DM, this can significantly alter your patient presentation. Several clinicians I work with relate this to a form of double crush injury: the nerve is being mechanically entrapped and is also receiving compression from other intrinsic sources. Continue to use your differential diagnosis skills to determine the source of one's symptoms. It may save your patient from an unnecessary surgery. -Jim

Next, I recommend a reassessment of the structures that were targeted during the initial evaluation. For example, if I found decreased mobility of the AA joint on the eval day, I would definitely be sure to reassess that prior to performing a manipulation - if warranted. With daily activity, joint mobility, flexibility, etc. can easily change due to something that happened between treatment sessions. And if a previously hypomobile joint is now normal, why mobilize it? Now I am not saying we should perform a complete re-examination of the objective section, but if the plan for the day involved manual therapy, I recommend assessing the targeted structures first. In cases like SIJ Dysfunction, maybe you reassess the pelvic alignment each session. How thorough you need to be is determined by dysfunction location, severity of injury, and various individual patient factors.

After finding the dysfunctional areas of mobility, I typically perform my manual therapy. My goal is to give the patient as much mobility in the limited structures as possible to the norm. Any limitation can lead to a compensation of hypermobility in adjacent or distant structures that may be the source of the pain. With the sedentary aspects of our lives, degeneration has become an expected normal development. While we would like to acquire true normal motion in everyone, it is not always feasible. I should note that some clinicians may prefer the patient do a warm-up prior to manual therapy or the reassessment as that may have an impact on treatment performance and clinical findings. Personally, I determine the need of a warm-up based on each individual patient. (I also should note not every patient requires manual therapy). Once I have completed my manual therapy, I go back to reassessing. Is the previous hypomobile joint now hypermobile? Is the previously painful motion or action now pain-free or less painful? We need to be certain our manual therapy had the desired outcome. As Nick Rainey states in a previous guest post, this is know as an asterisk sign (test-treat-retest). We may find that our previous assessment was inaccurate or that we need to spend a little more time with manual therapy in order to reach our goal. It is at this time that I proceed to therapeutic exercise/neuro re-ed. I truly believe it is important to complete your manual therapy first before moving this stage. With manual therapy, we often acquire new ranges of motion due to changes in joint mobility/tissue length/neural tension. While this is important, it is essential we use exercises to lock in the changes. We must retrain the body to move in those new ranges; otherwise, we are setting the patient up for re-injury. As Gray Cook has said, our bodies adapt dysfunctions often as a form of protection. If you free up the dysfunctional tissues, you are putting the patient at risk. Finally, I recommend finishing up each treatment session with another subjective portion. See how the patient immediately responds to that day's work. Some treatments have an immediate effect and again can impact our plan for the next session. As is typical, every patient is different and may require a different sequence for the treatment. This is merely an outline of how I work with my orthopaedic patients typically. There are more than a few indicators for adding, subtracting, or re-ordering the plan for that day! -Chris  Recently, Medicare released a list of the total payments of the more than 880,000 medical providers in 2012. The total cost of these payments was ~$77 billion. While medical doctors, specifically ophthalmologists and cardiologists, were at the top of this spending list, there were a few physical therapists that had an alarmingly high number of payments. Naturally, the media latched onto this information. This past Sunday The New York Times published an article about one physical therapist in Brooklyn who billed four million dollars in Medicare in 2012. The four million dollar figure is staggering because on average physical therapists collected $49,000 in Medicare payments in that same time frame. In the article, The New York Times goes on to say "one thing is certain, physical therapy has become a Medicare gold mine." This blanket statement about the profession of physical therapy is far from true. The majority of practitioners billed within their expected range. Fortunately, the APTA was quick to react to this article. In a letter to the editor, President Paul Rockar responds to The New York Times article. Thank you to our President and the APTA for keeping everyone up to date and aware of the issues challenging our profession. -Jim References:

Creswell, Julie, and Robert Gebeloff. "One Therapist, $4 Million in 2012 Medicare Billing." The New York Times. The New York Times, 27 Apr. 2014. Web. 29 Apr. 2014. |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed