- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

Assess and Reassess! While these words might sound easy, as a novice clinician I often find myself clinging to a single deficit and treating that impairment. I become so focused on the intervention, positioning, and client's initial reaction to the treatment, that I forget to perform a proper reassessment. This strategy can work for a while, but it is truly fixing the source of a client's problems? I sometimes fail to see the global effects I am having on the patient. In this post, Mike Reinold discusses the importance of continually assessing a patient's impairments, quantifying the impairment, treating it, and then reassessing the patient's response. Reassessment allows your treatment sessions to be more individualized, can be diagnostic, and most importantly builds client confident and compliance.

0 Comments

One of the common findings in individuals with low back pain is poor utilization of the core musculature. The TA (transversus abdominus) has been found to be highly suspect in these cases. Any activity that involves movement of the extremities, first requires some sort of weight shift (it may be small) to assure stability. This is usually accounted for by a contraction of the TA right before the movement of the extremity. Studies have found that individuals with low back pain have delayed recruitment and decreased motor firing of the TA in activities. A common therapy technique in individuals with low back pain is to provide neuromuscular education on how to first fire the TA (and other core muscles) and then utilize them during daily activities. The theory is that since the TA encircles the abdomen/core (when combined with the internal obliques) and connects to the thoracolumbar fascia. When the TA contracts, it stiffens the fascia and creates a stabilized cylinder that is the core! There have been many exercises developed with the focus on isolating and educating usage of the TA, such as pelvic tilts. This study looked at the potential for using co-contraction to increase the motor control of the TA. The researchers found increased activity and thickness of the TA when resisted ankle dorsiflexion was combined with the abdominal draw-in maneuver. While the results are very interesting, there are many things that should be considered when examining this study. First of all, the study had a low sample of participants at 40 individuals that were conveniently selected. The measuring of TA baselines and improvements were questionable as well. Surface EMGs were used to measure activity and can receive interference relatively easily from other muscles due to their proximity. Ultrasound imaging was used to measure the thickness of the TA and other abdominal musculature. The methods to this study were questionable, but the results provided interesting findings that could potentially be incorporated in future studies and interventions. Anatomy Review ("Kendall"): Transversus Abdominus (TA): Origin: inner surfaces of cartilages of the lower 6 ribs, interdigitating with the diaphragm; thoracolumbar fascia; anterior 3/4 of internal lip of the iliac crest; and lateral 1/3 of the inguinal ligament. Insertion: linea alba by means of a broad aponeurosis, pubic crest, and pecten pubis. Innervation: T7-12, L1 iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal, ventral divisions. Action: acts like a girdle to flatten the abdominal wall and compress the abdominal viscera; upper portion helps to decrease the infrasternal angle of the ribs, as in expiration. This muscle has no action in lateral trunk flexion, except that it acts to compress the viscera and to stabilize the linea alba, permitting better action by the anterolateral trunk muscles. References:

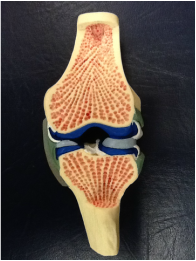

Chon SC, You JH, Saliba SA. "Cocontraction of ankle dorsiflexors and transversus abdominis function in patients with low back pain." J Athl Train. 2012;47(4):379-89. Web. 09/28/2012. Kendall F, McCreary E, Provance P, Rodgers M, Romani W. "Muscles: Testing and Function with Posture and Pain." 5th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005. 197. Print.  In each knee, there is a medial and lateral meniscus attached to the proximal tibia that accepts the femoral condyles. The shape and composition of the menisci serve to increase the surface area of contact at the tibiofemoral joint. On the medial side, the meniscus is oval-shaped and attaches to the capsule and medial collateral ligament. On the lateral side, the meniscus is more circular and attaches to the lateral capsule. The cusp-like form of the meniscus conforms to the convex shape of the appropriate femoral condyle. Due to the structural makeup of the meniscus, compression during weight-bearing activities is absorbed via circumferential tension (hoop stress) and allows the meniscus to deform peripherally. By increasing the surface area, there is a resultant decrease in stress on both the tibia and femur. Each meniscus is anchored to the intercondylar area at the anterior and posterior horns. The peripheral aspects of each meniscus adheres to the tibial plateau and capsule via coronary ligaments, and an anterior transverse ligament connects to two menisci. With the loose attachments of the meniscus to the knee, significant movement is permitted by each meniscus. According to Neumann, the quadriceps and semimembranosus muscles attach to both menisci, while the popliteus muscle attaches to the lateral meniscus only. These muscular attachments can aid in stabilizing the relatively loose menisci during knee motion, but also can put too much stress on the meniscus during recovery from surgery. The menisci are also important for guiding arthrokinematic motion, proprioception, lubricating the articular cartilage, and stabilizing the knee. The mechanism of injury can often be useful in diagnosing the pathology. In traumatic cases, the meniscus is often torn by twisting of the femur on a flexed knee and fixed tibia. Due to the proximity of the menisci to other structures of the knee (MCL, ACL, etc.), common mechanisms of injury, such as a valgus collapse, can injure the meniscus as well (remember the medial meniscus attaches to the MCL). Patients often complain of having "twisted" their knee, hearing a "pop," joint line pain that is increased during weight-bearing, and possibly having the joint lock in place. It is widely accepted that the medial meniscus is torn more frequently than the lateral, however, one of the studies we looked at stated that the opposite might be true. Meniscal tears are commonly associated with ACL injuries. During an ACL rupture as a result of a valgus collapse, it is the lateral meniscus that has been found to be torn more frequently due to the compression forces between the tibia and femur. The medial meniscus is found to be torn more frequently in the chronic ACL-deficient knees as a result of repetitive translation of the tibiofemoral joint. In the acute cases, we may or may not see joint effusion and a flexed-knee gait pattern. Patients may be unable to achieve full extension, due to a block caused by a meniscal tear. When the mechanism of injury is not clear, or in non-traumatic cases, we as clinicians have many options to assess the integrity of the menisci. The McMurray Test is used commonly when assessing the menisci, but due to its low diagnostic accuracy, should only be used when clustered with other tests (pain with flexion overpressure, pain with extension overpressure, joint line tenderness, and a hx of locking - check out the knee homepage for the criteria!). Another special test, the Thessaly Test, has very good diagnostic accuracy. As far as imaging goes, MRIs are commonly used with a contrast to identify meniscal tears, but do not always visualize well enough to be certain. Arthrograms are a cheaper option, but are not as sensitive and specific as an MRI. An arthroscopy can increase certainty with direct visualization. There are many factors that should come into consideration when addressing a meniscal injury in an individual. One of the most important ones is age. The standard meniscus has good blood supply to the peripheral 1/3, decent blood supply to the middle 1/3, and poor blood supply to the central 1/3. Obviously, the blood supply can translate into ability to regenerate. When we are younger (especially the skeletally immature), there is increased vascularity throughout the entire meniscus, which translates into an even higher potential for regeneration. With this knowledge, it is widely accepted that adolescents will have a surgical procedure for a meniscal repair. In a study on young athletes, meniscal repairs had good results for peripheral and central tears. The study used the "inside-out" technique that has shown significant success. Another factor that comes into play is whether or not an ACL reconstruction occurred at the same time. Many studies have shown that individuals who simultaneously had their ACL reconstructed and a meniscal repair had better results. The theory is that the hemarthrosis created by the ACL reconstruction aided in healing factors for the meniscus. Studies have also shown that the risk for retearing the meniscus is higher when located centrally, where there is poorer blood supply. Stability of the knee can play a role in the likelihood of retearing the meniscus as well. In an unstable knee, additional arthrokinematic motion can occur; thus, additional stress can be placed on the meniscus. A large contributing factor to potential for repair is the type of tear i.e. bucket-handle, longitudinal, radial, etc. The issue is that this cannot be identified without direct visualization. Tears like a bucket-handle often are partially removed instead of repaired, due to the destruction of the collagen tension lines. Another important note is that these factors can play a role in the pace of the rehab program. With characteristics that are shown to have increased healing rates, a more aggressive rehab protocol can be utilized. In the adult population, since repairs are less likely to be successful, a partial meniscectomy is often preferred over a total meniscectomy. In the past, total meniscectomies were performed frequently without concern; however, over time a link has been shown between those who had their entire meniscus removed and the development of osteoarthritis. As the understanding of the importance of the menisci increased, we learned how the menisci were responsible for decreasing the stress placed on the articular cartilage and bone. As a result of this finding, surgical procedures were adjusted to try and preserve the meniscus as much as possible, which led to thedevelopment of the partial meniscectomy. In those who choose to still pursue a complete meniscectomy, it has been shown that adherence to an exercise program can delay or reduce the risk of developing OA. One of the major correlations for developing OA is reduced thigh muscle strength. It is known that an exercise program can reduce this risk factor. In a partial meniscectomy, the tear is often removed and the remaining meniscus is smoothed out, so that any fraying cannot lead to another tear. In elderly individuals, where degeneration injuries are more common, studies have shown an initial bout of conservative therapy (physical therapy) can often delay or sometimes eliminate the need for a partial meniscectomy, however, this is a debatable topic where further research is needed. One study in particular found that in an exercise group vs. an arthroscopic partial meniscectomy + exercise group, no difference was found in results. It should be noted that the participants only had non-traumatic meniscal injuries. In the athletic population, some athletes have the option of returning to sport to finish the season, while having the meniscal tear remain. This could delay surgery until the season is finished. However, if the athlete was unable to withstand the symptoms, surgery could be utilized. The article did not discuss if conservative therapy was used during the season to try and alleviate symptoms. An important consideration is the time period between injury occurrence and surgical procedure. An article found that better results were achieved if the repair occurred within 8 weeks of injury for traumatic meniscal injuries. The longer the tear was present, the more likely OA developed. As far as rehabilitation of individuals following meniscal repairs goes, PTs are often found following the protocol of the surgeon in a step-by-step process. As expected, there is a wide variety of both conservative and accelerated programs that can vary from 10 weeks to 7 months for return to sports. Research is underway that will hopefully aid in determinig the appropriate speed of a rehab program. A study on animal meniscal repairs found that 80% of the tensile strength was achieved after 12 weeks. Variable factors include whether or not an immobilization period is used (and how long that phase is), weight-bearing restrictions, ROM limitations based on time from surgery, concomitant surgeries such as ACL reconstruction can influence the rehab protocol, and of course activities that stress the meniscal repair more forcefully. One study showed that prolonged immobilization is linked to decreased collagen content. It is interesting to note that it is not necessarily the weight-bearing element that stresses the meniscus, but the combination of weight-bearing with gliding of the tibio-femoral joint and of course rotation of the knee. As physical therapists we work on treating the patients' impairments, such as flexibility, strength deficits (especially the quads), and tasks that involve a high level of balance and neuromuscular coordination. Sport-specific training is included, when appropriate. An additional method of treatment that should be considered is the use of aquatic therapy. Aquatic therapy has been used in accelerated ACL rehab programs with success and could find benefit with meniscal repairs as well. The pool environment addresses the concern of weight-bearing and stress put on the repair. More advanced exercises can potentially be implemented earlier in the pool due to that decrease in stress. Something to consider, however, is the resistance put on hamstrings, due to their attachment to the menisci. Be sure to know any limitations the surgeon has on hamstring activity before using the pool. Some more experimental methods are out there to try and facilitate meniscal repair. The fibrin clot is a procedure where a fibrin clot matrix is injected into the meniscal tear to promote normal healing processes. While the meniscus was repaired, it was unable to resist the stresses that a normal, healthy meniscus can withstand, so the additional healing factors can potentially improve the process. Another procedure being explored is vascular access channels. As the name might explain, tunnels are created to connect the vascular areas of the meniscus to the avascular areas that are damaged in order to try and redirect the healing nutrients to the injured site. This method has had positive results in the initial studies and could potentially be useful for particular cases! Synovial abrasion is a process that involves surgical irritation of the synovial lining of the knee. The purpose is to have the healing cells from the synovium aid in healing the damaged meniscus. This technique is used frequently during surgeries. Many researchers are also trying to develop working meniscal transplants. Right now there are various methods of transplants for a meniscus: fresh allografts, deep-frozen allografts, cryopreserved allografts, and freeze-dried allografts. Of the four listed there, the fresh allografts and cryopreserved allografts provided the best potential results, but the long-term outcomes are still unknown. On a related topic, researchers are also looking at constructing collagen scaffolds that can provide the characteristics necessary for fibrochondrocyte ingrowth that could lead to meniscal regeneration. Something to look out for in the future! A recent study utilized a treatment known as AposTherapy for individuals with degenerative meniscal injuries and potential development of OA. The researchers analyzed the gait of the participants. Each individual was then given shoes that had an element placed on the hindfoot and an element placed on the forefoot (customized following the results of the gait analysis) that were designed to alter the gait of the individual. Participants gradually built up tolerance wearing the devices each day. After 12 months, significant changes were noted in the participants' gait patterns, especially increased gait speed, SLS, and step length. When further research is done, this could be an interesting treatment option to delay the need for surgical intervention and could be useful for treating those at risk for developing OA as well. References: Brindle T, Nyland J, Johnson DL. "The meniscus: review of basic principles with application to surgery and rehabilitation." J Athl Train. 2001 Apr;36(2):160-9. Web. 09/22/2012. Elbaz A, Beer Y, Rath E, Morag G, Segal G, Debbi EM, Wasser D, Mor A, Debi R. "A unique foot-worn device for patients with degenerative meniscal tear." Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012 May 4. Web. 09/22/2012. Englund M, Roemer FW, Hayashi D, Crema MD, Guermazi A. "Meniscus pathology, osteoarthritis and the treatment controversy." Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012 May 22;8(7):412-9. Web. 09/22/2012. Ericsson YB, Dahlberg LE, Roos EM. "Effects of functional exercise training on performance and muscle strength after meniscectomy: a randomized trial." Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009 Apr;19(2):156-65. Web. 09/22/2012. Giuliani JR, Burns TC, Svoboda SJ, Cameron KL, Owens BD. "Treatment of meniscal injuries in young athletes." J Knee Surg. 2011 Jun;24(2):93-100. Web. 09/22/2012. Greis PE, Holmstrom MC, Bardana DD, Burks RT. "Meniscal injury: II. Management." J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002 May-Jun;10(3):177-87. Web. 09/23/2012. Herrlin S, Hållander M, Wange P, Weidenhielm L, Werner S. "Arthroscopic or conservative treatment of degenerative medial meniscal tears: a prospective randomised trial." Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007 Apr;15(4):393-401. Web. 09/22/2012. Kraus T, Heidari N, Švehlík M, Schneider F, Sperl M, Linhart W. "Outcome of repaired unstable meniscal tears in children and adolescents." Acta Orthop. 2012 Jun;83(3):261-6. Web. 09/22/2012. McCarty EC, Marx RG, Wickiewicz TL. "Meniscal tears in the athlete. Operative and nonoperative management." Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2000 Nov;11(4):867-80. Web. 09/22/2012. Neumann, Donald. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System: Foundations for Rehabilitation. 2nd edition. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier, 2010. 526-528. Print. Pyne SW. "Current progress in meniscal repair and postoperative rehabilitation." Curr Sports Med Rep. 2002 Oct;1(5):265-71. Web. 09/22/2012. Vanderhave KL, Moravek JE, Sekiya JK, Wojtys EM. "Meniscus tears in the young athlete: results of arthroscopic repair." J Pediatr Orthop. 2011 Jul-Aug;31(5):496-500. Web. 09/22/2012. Typically, External Rotation is the most limited motion in patients with adhesive capsulitis. The traditional manual therapy technique for these patients was an anterior glide mobilization to help increase external rotation ROM. This treatment was well accepted for a number of years because it agrees with the arthrokinematic principles. In recent years, there has been new evidence surfacing about the beneficial effects of posterior mobilizations for this patient population. In this article, the authors found that using a posterior glide mobilization (Kaltenborn Grade III sustained), with therapeutic ultrasound and upper extremity therapeutic exercises was the most effective for increasing external rotation ROM deficits in patients with adhesive capsulitis. They found that the posterior mobilization group had an average increase of 31.1 degrees of external rotation (after 3 treatment sessions), compared to only 3 degrees average for the anterior mobilization group. The article also found that patients with adhesive capsulitis often had a decreased rotator cuff interval space, pushing the humeral head anterior/ superior and not allowing normal posterior/ inferior motion. We must remember that at the glenohumeral joint, both anterior and posterior forces must be in coordination for proper stability. Anatomy and Kinesiology Review: |

| Superior Glenohumeral Ligament: Taut in adduction, inferior and a/p translations of the humeral head. | Middle Glenohumeral Ligament: Taut in anterior translation of the humeral head, especially in 45-60 d. of abduction; external rotation | Inferior Glenohumeral Ligament (has 3 parts): Axillary pouch: taut in 90 d. abduction, combined with a/p and inferior translations. Anterior band: taut in 90 degrees abduction and full external rotation; anterior humeral translation. Posterior band: taut in 90 d. of abduction and full internal rotation. | Coracohumeral Ligament: Taut in adduction; inferior translation of the humeral head; external rotation |

Kinesiology Reference:

Neumann, Donald. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System. 2nd Edition. Mosby Inc., 2012. Print.

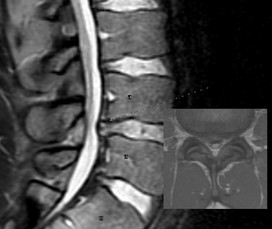

The diagnosis of disc herniation as the source of back pain is a controversial issue. There is a large proportion of the population that is asymptomatic and shows disc herniation in MRIs, which leads to the issue of the disc being incorrectly labeled as the source of the patient's complaints sometimes. With the appearance of a herniating disc, some surgeons and patients jump to the conclusion that a surgical procedure is necessary for correction without considering conservative treatment. While surgery can be effective for some individuals, it may represent an expensive overreaction to the patient's symptoms.

The study we looked at this week was a systematic review of conservative treatment for lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy. Studies were only included if the patients were over 18 years old and referred with leg pain (with or without low back pain). 75% of the patients had to have a confirmed lumbar disc herniation through MRI or CT as well. Participants with discs that were only "bulging" were not included. Studies were also excluded if surgery was performed or an injection was used; accupuncture, along with other physical therapy interventions, was labeled as conservative therapy.

The review found that advice had poorer short and intermediate outcomes for back pain and leg pain compared to surgical microdiscectomy, but there was no difference in the long term. Those who pursued surgery had better function compared to the advice group at short-term follow-up, but no difference was noted at intermediate and long-term outcomes. Manipulation was found to be effective as long as the annulus was still intact. No difference was found between traction, Low Level Laser Therapy, and ultrasound, but traction had good results when combined with electrotherapy and medications in the short term. The review found moderately strong evidence that stabilization exercises were better than no treatment at all. It should be noted that there are possible adverse effects linked between ibuprofen use and traction.

While this article offers some information on the effectiveness of various conservative treatment methods in treating lumbar disc herniation radiculopathy, it does not sufficiently examine the entire scope of physical therapy interventions, such as repeated motions, extension based exercises, neuromuscular education of the core, etc. While there are plenty of studies out there that look at the effectiveness of interventions like repeated motions, neuromuscular education, and core stabilization, there weren't many studies looking at those treatment methods that fit the specific inclusion criteria of this systematic review. It does not mean they are not effective, but it points out an excellent research opportunity for anyone interested. Be sure to keep an eye out for some posts coming out in the near future for treating low back pain.

Reference:

Hahne AJ, Ford JJ, McMeeken JM. "Conservative management of lumbar disc herniation with associated radiculopathy: a systematic review." Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010 May 15;35(11):E488-504. Web. 09/15/2012.

This study looked at 28 consecutive patients retrospectively that were treated with kineseology taping. They used a couple methods: a) tape was placed along the unaffected side's SCM and upper trap with no stretch for muscle facilitation b) tape was applied along the SCM on the affected side with a stretch for muscle relaxation c) a combination of the two. The study found the muscle relaxation technique to be the most successful, even though the other 2 methods were successful as well. While taping may be of benefit when treating infants with CMT, it should not be used alone. Consider using the taping technique as an adjunct to the rest of your interventions to potentially facilitate a more efficient therapy session.

It should be noted that the results of this study should be considered carefully. This was a retrospective, non-randomized study that lacked blinding of the physical therapist. Further research is needed to explore the potential benefits of kineseology taping for CMT more expansively. Check out the article for yourself!

Anatomy Review of Sternocleidomastoid ("Kendall"):

Origin: Sternal head: cranial part of manubrium

Clavicular head: medial 1/3 of clavicle

Insertion: lateral surface of mastoid process; lateral 1/2 of superior nuchal line of occipital bone

Action: Ipsilateral lateral flexion, contralateral rotation, extension of upper cervical spine, flexion of lower cervical spine

Innervation: accessory nerve (CN XI), C1-2

Reference:

Kendall F, McCreary E, Provance P, Rodgers M, Romani W. "Muscles: Testing and Function with Posture and Pain." 5th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005. 148-149. Print.

Ohman A. "The Immediate Effect of Kinesiology Taping on Muscular Imbalance for Infants with Congenital Muscular Torticollis." PM&R: The journal of injury, function and rehabilitation. 4.7 2012. Print. 504-508.

As with many tendinopathy pathologies, achilles tendinopathy is often diagnosed as tendinitis and treated improperly. It has been shown that neovascularization is abundant in these structures and is not necessarily an inflammation issue (a topic we will examine more closely in the near future!). As with any other injured individual, they will present with many impairments that should be treated regularly (stretching, strengthening, etc.), but there are certain interventions that have been shown to have higher evidence.

Low-Level Laser Therapy (LLLT) is an intervention that is becoming more prominent today in treating many different pathologies, one of which is achilles tendinopathy. In the study we looked at, there was no difference between eccentric exercises + placebo and eccentric exercises + LLLT (actually the placebo group performed better in one of the outcomes!). Consider this evidence when choosing your interventions.

As you might have expected, eccentric exercises have been shown to be the best treatment method for patients with achilles tendinopathy. Even after 5 years of treatment, improvements were shown; although, some pain was still present in some individuals. One of the issues with using eccentric exercises for individuals with achilles tendinopathy that has become prevalent is the effectiveness for those with insertional vs. mid-portion achilles tendinopathy. Insertional achilles tendinopathy results in the tendon being most painful where it attaches to the calcaneus; mid-portion achilles tendinopathy is proximal to that. The studies have shown high evidence in regular eccentric exercises (loading into dorsiflexion) for mid-portion pain, but not insertional pain. However, there has been recent research that shows a modification of the exercise can improve the results of insertional pain. Perform the eccentric exercise the normal way, except do not load into dorsiflexion. Approximately 2/3 of the sample showed improvements!

Another alternative treatment method that is becoming more well-known involves using autologous-combined plasma injections combined with standard treatments-wearing a pneumatic boot, receiving ultrasound, and eccentric exercises. Occasionally, you hear about professional athletes receiving this type of treatment for other joints in Europe, since it is not usually performed in the U.S. While the study is still preliminary, it's still something to keep your eye on in the future!

References:

Deans VM, Miller A, Ramos J. "A Prospective Series of Patients with Chronic Achilles Tendinopathy Treated with Autologous-conditioned Plasma Injections Combined with Exercise and Therapeutic Ultrasonography." J Foot Ankle Surg. 2012 Jul 21. Web. 09/09/2012.

Fahlström M, Jonsson P, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H. "Chronic Achilles tendon pain treated with eccentric calf-muscle training." Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2003 Sep;11(5):327-33. Epub 2003 Aug 26. Web. 09/09/2012.

Jonsson P, Alfredson H, Sunding K, Fahlström M, Cook J. "New regimen for eccentric calf-muscle training in patients with chronic insertional Achilles tendinopathy: results of a pilot study." Br J Sports Med. 2008 Sep;42(9):746-9. Epub 2008 Jan 9. Web. 09/09/2012.

Mafi N, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H. "Superior short-term results with eccentric calf muscle training compared to concentric training in a randomized prospective multicenter study on patients with chronic Achilles tendinosis." Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9(1):42-7. Web. 09/09/2012.

Tumilty S, McDonough S, Hurley DA, Baxter GD. "Clinical effectiveness of low-level laser therapy as an adjunct to eccentric exercise for the treatment of Achilles' tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial." Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012 May;93(5):733-9. Web. 09/09/2012.

van der Plas A, de Jonge S, de Vos RJ, van der Heide HJ, Verhaar JA, Weir A, Tol JL. "A 5-year follow-up study of Alfredson's heel-drop exercise programme in chronic midportion Achilles tendinopathy." Br J Sports Med. 2012 Mar;46(3):214-8. Epub 2011 Nov 10. Web. 09/09/2012.

Verrall G, Schofield S, Brustad T. "Chronic Achilles tendinopathy treated with eccentric stretching program." Foot Ankle Int. 2011 Sep;32(9):843-9. Web. 09/09/2012.

A more developed review of the research behind these and many more interventions is located in the practice guidelines below for achilles tendinopathy!

Carcia CR, Martin RL, Houck J, Wukich DK. "Achilles pain, stiffness, and muscle power deficits: achilles tendinitis." J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010 Sep;40(9):A1-26. Web. 09/09/2012.

| A hot debate is often presented on whether or not patients of a particular diagnosis would benefit from conservative treatment or surgical intervention. Of course, there is no universal guideline that determines the appropriate treatment choice for everyone. Osteoarthritis is a pathology that seems to be affecting people more and more. The most common joints in which this is seen include the knee and hip. With our current understanding of the pathological process of OA and imaging techniques, we are continually improving in our ability to spot patients that are likely to develop arthritis, or in this case identify patients with prearthritic hips. |

Interestingly, just under half the sample were satisfied with the outcome of just obtaining conservative treatment, while the rest required surgical intervention. With such a large portion responding favorably to physical therapy, it would appear a trial of PT be attempted before surgery is considered in most individuals with prearthritic hip complaints, especially due to the rigid structure of the conservative care plan. Physical therapists were instructed to follow a protocol's guidelines when treating the patients, while only slightly individualizing the care. Most of the interventions were educational-based, so a more impairment-focused care plan could potentially have even further benefit!

Reference:

Hunt D, Prather H, Harris Hayes M, Clohisy J. "Clinical Outcomes Analysis of Conservative and Surgical Treatment of Patients with Clinical Indications of Prearthritic, Intra-articular Hip Disorders." PM&R: The journal of injury, function and rehabilitation. 4.7 (2012): 479-486. Print.

This article does a nice job exploring the various core strengthening exercises that we often prescribe patients. The article highlights muscle activation of the upper and lower rectus abdominus, external oblique, internal oblique, lumbar paraspinals, latissimus dorsi, and rectus femoris muscles during common therapeutic exercises. It demonstrates which exercises elicit the highest maximum voluntary isometric contractions and how to get the most bang for your buck when selecting core interventions.

Highlights:

-The Roll-out Exercise and Pike Exercise were the most effective in activating core muscles.

-Prone Position swiss ball exercises were as effective as kneeling and supine exercises.

-The traditional crunch has fairly high upper rectus abdominus muscle activation, but lower activation in the internal oblique, external oblique, and lower rectus abdominus.

Muscle Review:

| Rectus Abdominus: Origin: Pubic Crest and Symphysis Pubis. Insertion: Costal Cartilages of ribs 5-7 and xiphoid process. Action: Flexes the vertebral colum and compresses the abdomen. Innervation: Intercostal Nerves 7-12 | External Oblique: Origin: External Surfaces of ribs 5-12. Insertion: Anterior Iliac Crest, abdominal aponeurosis to linea alba. Action: Flexes the vertebral column, laterally flexes vertebral column, and compresses the abdomen. Innervation: Intercostal Nerves 8-12, iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves. | Internal Oblique: Origin: Anterior Iliac crest, lateral half of the inguinal ligament, and thoracolumbar fascia. Insertion: Costal Cartilages of ribs 8-12. Aponeurosis of Linea alba. Action: Flexes vertebral column, laterally flexes vertebral column, and compresses abdomen Innervation: Intercostal Nerves 8-12, iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves. |

| One of the common knee complaints encountered in athletes (and other individuals) is patellofemoral pain syndrome. It is a difficult pathology to treat successfully with permanent results. While not completely agreed upon, it is thought that the cause for PFPS is a combination of the reaction force and the contact area. With the alignment of the proximal attachment of the quadriceps and the distal attachment of the patellar ligament, there is a lateral pulling force (the Q-angle) that compresses the patella against the lateral femoral articular surface. |

There have also been studies on strengthening the quadriceps muscles with reported success. In the study, both closed-chain and open-chain exercises were used with improvement in function and pain.

Some alternate methods that can be included in treating PFPS are taping of the patellofemoral joint and utilizing orthotics. While there has not been much evidence in using orthotics, if the patient is reporting a decrease in pain with use, it would not hurt for them to keep using the device. Taping, on the other hand, has shown to have success in improving pain and function when combined with exercise. The study looked at here utilized a program with 2 initial weeks of taping followed by exercise that had successful long-term outcomes.

A final study we looked at was exercise vs. exercise and knee arthroscopy. Both immediate and 5-year follow-up reported improvements in pain and function; however, there was no significant difference between the two groups, suggesting that surgery may not be necessary for all individuals.

From reviewing these articles, we like to try and take a conservative approach initially with patients of PFPS by including taping, exercises that strengthen the quads and hip external rotators/extensors, and possibly orthotics. Of course, consider using additional exercises and stretches with these patients, but surgery may not be the option for everyone. Check out the articles to decide for yourselves!

References:

Bolgla LA, Boling MC. "An update for the conservative management of patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic review of the literature from 2000-2010." Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2011 Jun;6(2):112-25. Web. 09/02/2012.

Kettunen JA, Harilainen A, Sandelin J, Schlenzka D, Hietaniemi K, Seitsalo S, Malmivaara A, Kujala UM. "Knee arthroscopy and exercise versus exercise only for chronic patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized control trial." Br J Sports Med. 2012 Mar;46(4):243-6. Epub 2011 Feb 25. Web. 09/02/2012.

Khayambashi K, Mohammadkhani Z, Ghaznavi K, Lyle MA, Powers CM. "The effect of isolated hip abductor and external rotator muscle strengthening on pain, health status, and hip strength in females with patellofemoral pain: a randomized control trial." J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012 Jan;42(1):22-9. Epub 2011 Oct 25. Web. 09/02/2012.

Paoloni M, Fratocchi G, Mangone M, Murgia M, Santilli V, Cacchio A. "Long term efficacy of a short period of taping followed by an exercise program in a cohort of patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome." Clin Rheumatol. 2012 Mar;31(3):535-9. Epub 2011 Nov 3. Web. 09/02/2012.

Swart NM, van Linschoten R, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, van Middelkoop M. "The additional effect of orthotic devices on exercise therapy for patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic review." Br J Sports Med. 2012 Jun;46(8):570-7. Epub 2011 Mar 14. Web. 09/02/2012.

Insider Access pages

We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!

Archives

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

October 2016

September 2016

August 2016

July 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

March 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

November 2015

October 2015

September 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

May 2015

April 2015

March 2015

February 2015

January 2015

December 2014

November 2014

October 2014

September 2014

August 2014

July 2014

June 2014

May 2014

April 2014

March 2014

February 2014

January 2014

December 2013

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

August 2013

July 2013

June 2013

May 2013

April 2013

March 2013

February 2013

January 2013

December 2012

November 2012

October 2012

September 2012

August 2012

Categories

All

Chest

Core Muscle

Elbow

Foot

Foot And Ankle

Hip

Knee

Manual Therapy

Modalities

Motivation

Neck

Neural Tension

Other

Research

Research Article

Shoulder

Sij

Spine

Sports

Therapeutic Exercise

RSS Feed

RSS Feed