- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

|

23 1/2 hours is a short video by Dr. Mike Evans regarding the BEST intervention for patients of all diagnosis'. He assessed risk factors such as drinking, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, and more. After years of research, he found one intervention that was the single most important thing you could do for your health. The video has some great information for you as a health care practitioner, and also can be used as a teaching tool for your patients.

3 Comments

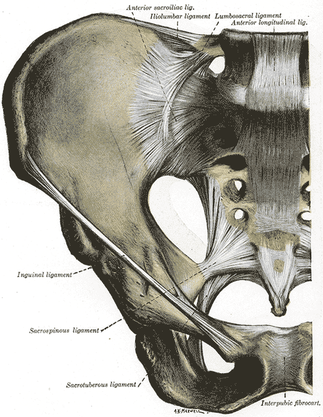

Jackson and Porter bring up the fact that there is essentially no research on the topic of non-painful SIJ Dysfunction. Once again, just because there is no research in an area, does not indicate that it should be dismissed as non-existent. We tend to become overly reliant on our pain provocation tests. So what do we do? We definitely recommend still utilizing your clusters, palpating soft tissue, and utilizing subjective information such as Fortin's Sign to aid in diagnosing painful SIJ Dysfunction. As for non-painful dysfunction, practice and implement the motion restriction tests that you are taught in school. We are trained to be competent in tests like Lachman's and Drawer Tests that require identification of differences in movement around a few millimeters. In theory, we should be able to identify some abnormalities in the sacroiliac joint as well. Now, we recognize that research has shown poor reliability for those tests and for good reason, but they may still aide in picking up severe restrictions that will lead to diagnosis and treatment in order to facilitate the return to normal mobility. Reference:

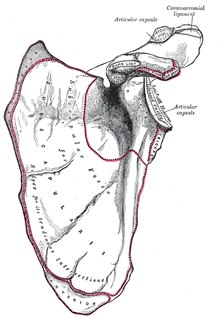

Jackson R and Porter K. The Pelvis and Sacroiliac Joint: Physical Therapy Patient Management Utilizing Current Evidence. Current Concepts of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy, 3rd Ed. La Crosse, WI. 2011.  We may have touched on Lower Crossed Syndrome in the past, but it is seen so frequently that is does not hurt to mention it again. Lower Crossed Syndrome is a common musculoskeletal disorder related to postural imbalances. In this syndrome, the patient will often present with short/strong hip flexors and lower back extensors. Contrarily, they will have lengthened/ weak abdominals and gluteal muscles. These diagonal patterns of imbalance create an imaginary "X" on the patient (hence the name "crossed" syndrome). This syndrome is typically seen in people who sit for long periods of time, allowing the hip flexors to shorten. Additionally, it can be found in athletes who use repetitive movements such as running. Clinically you will see an anterior pelvic tilt, lumbar lordosis, lateral rotation of the lower extremities, genu recurvatum, and alterations in arm/leg swing patterns during gait. The anterior pelvic tilt and lumbar lordosis may create increased compressive forces along L4, L5, and S1. Any compromise of the lumbopelvic muscles may lead to instability throughout the lower extremities, so your patient may present with low back pain, knee pain, or ankle issues. For example, the gluteus maximus is an important eccentric decelerator for hip flexion, internal rotation, and adduction. If the gluteus maximus is weak, it cannot stabilize the tibiofemoral joint properly during dynamic motion. Additionally, the tight hip flexors are placed in a better position for muscle contraction and consequently receive increased neural input. This reciprocal inhibition can lead to further tibiofemoral instability and knee pain. When treating these patients, postural awareness, lifestyle modification, stretching, and strengthening will be important. Remember to address the shortened muscle prior to intensive strengthening. The patient needs to have adequate muscle length before beginning a strengthening program. Also, always direct your attention to the cause of the patients symptoms. While they may be having regional symptoms, the true cause may be either proximal or distal to the symptoms.  Are you familiar with Snapping Scapula Syndrome? If your school's program was anything like ours, you might be relatively unaware of this pathology, and whenever that occurs, it makes it difficult to identify patient suffering from various disorders. The Sports Physiotherapist recently did an excellent review on the pathology, signs/symptoms, diagnosis, imaging, and conservative/surgical treatment of this scapula disorder. Videos are included to show what the snapping actually looks like, along with some of the exercises recommended for the syndrome. Check out the Sports Physiotherapist for a lot of other great material as well.  While relatively new to the field of Physical Therapy, Clinical Prediction Rules have been used in medicine for a very long time (for example the Deep Vein Thrombosis CPR). These rules have been designed to improve clinical decision making and assist the practitioner in diagnosis, prognosis, and intervention planning. Childs and Cleland point out that "CPRs provide practitioners with powerful diagnostic information from the history and physical examination that may serve as an accurate decision-making surrogate for more expensive diagnostic tests." Not only can CPR's help curb the rising costs of healthcare, using this high level of evidence is especially important in the direct access setting where more extensive diagnostic testing has not been performed. In addition to diagnosis, other CPRs can aide in the classification and subgrouping of patients to guide you in intervention planning. Now that you know CPRs are important, what are these clinical prediction rules and where can you access them? Fortunately John Synder at the Orthopedic Manual Therapist recently compiled a list of them. Check them out HERE! References:

Childs J and Cleland J. (2006). Development and Application of Clinical Prediction Rules to improve decision making in Physical Therapist Practice. PHYS THER. 2006. Jan;86(1):122-131. Web. 13 Aug 2013.  Much of the recent research has suggested that it is best to warm-up prior to exercise to decrease risk of injury, deviating from the previously accepted practice of stretching. Mike Reinold's recent post discussed some of the disparities between the more recent and older research on the topic. One of the major factors brought up is that stretching less than 30 seconds is not associated with increased injury risk. In fact, stretching longer than 30 seconds is okay as well if combined with some form of dynamic exercise. The question of "why" arises. As we've discussed before, a stretch only changes tissue length after 30 seconds of static hold. In school, we were taught that when stretching, we should proceed to strengthen in the newly acquired range. This is important so that we can maintain that range and have control over the joint. Without strengthening/neuromuscular training in the new range, the joint loses stability. We really shouldn't be trying to increase muscle length prior to any competition, especially since the muscles/joints are weak at those points. Our theory is that stretching less than 30 seconds or combining stretching with dynamic exercises activates or maintains some neuromuscular tone/reflex that protects the joint in end range by decreasing perceived stiffness. Fatigue has been shown to play a role in stretch reflex inhibition, thus decreasing performance (Ross et al, 2001). Just as concerning, prolonged passive stretches have been shown to an effect on the tendinous tissue, such as stress relaxation and plastic deformation (Avela et al, 2004). By keeping stretches under 30 seconds or adding dynamic exercises, this protective reflex is not lost. Many PT schools teach that ballistic stretching can be hazardous to the tissue, but with these findings, do you think that type of exercise actually does have a role in performance enhancement/injury prevention? References:

Avela J, Finni T, Liikavainio T, Niemelä E, Komi PV. (2004). Neural and mechanical responses of the triceps surae muscle group after 1 h of repeated fast passive stretches. J Appl Physiol. 2004 Jun;96(6):2325-32. Web. 11 Aug 2013. Avela J, Kyröläinen H, Komi PV. (1999). Altered reflex sensitivity after repeated and prolonged passive muscle stretching. J Appl Physiol. 1999 Apr;86(4):1283-91. Web. 11 Aug 2013. Chalmers G. (2004). Re-examination of the possible role of Golgi tendon organ and muscle spindle reflexes in proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation muscle stretching. Sports Biomech. 2004 Jan;3(1):159-83. Web. 11 Aug 2013. Ross A, Leveritt M, Riek S. (2001). Neural influences on sprint running: training adaptations and acute responses. Sports Med. 2001;31(6):409-25. Web. 11 Aug 2013.  The average adult breathes 12-20x/minute, which accounts to over 20,000 breaths/day. Ideally, the diaphragm is the major muscle of inspiration. When abnormal breathing patterns develop, accessory muscles (scalenes, SCM, upper trapezius, pectorals) are forced to be used more. In other words, these muscles have the potential to be used improperly >20,000x/day. Scary right?! While various breathing pattern abnormalities exist, a commonly seen pattern is the "chest breather." The chest breather does not fully engage his/her diaphragm and often has decreased lung volumes. These patients often incorporates their anterior accessory muscles of inspiration which can pull them into a forward head and rounded shoulder posturing: a posture we see in many of our clients. Their imbalances go deeper than what is seen by observation alone. Because the chest breather has decreased lung volumes, he/she may be in a constant sympathetic state to supply sufficient oxygen to the bodies tissues. Consequently, they may have increased muscle tone, anxiety, and a variety of other PNS and CNS symptoms. In a post written by Mike Reinold in late April, he highlights two studies that show the importance of proper breathing. One study interestingly discovered increased EMG activity of the scalene and trapezius muscles while typing. As students, who spend most of their day at a computer, this is something to consider. This could be contributing to neck pain and stiffness that so many students have. Additionally, breathing exercises maybe a good place to start for your sedentary office worker with chronic neck pain. Reinold also mentions several treatment strategies to initially assess breathing technique: 1. Breath Holding Test. Decreased breath holding my demonstrate an intolerance to CO2 build-up. 2. Belly/Chest Test. Have the patient place one hand at their naval and their second hand at the sternum. Assess which hands moves further. Is there a change is sitting vs. supine? With a deep breath, ~90% of motion should come from the lower hand, indicating good diaphragmatic breathing. This test can later be used as an intervention. It is a simple way to provide external cueing to the patient to activate their diaphragm. 3. Seated Lateral Expansion. Have the patient place a hand on either side of their thorax. Take a deep breath in and feel for rib movement symmetry. Again, if one side is moving differently than the other, hand cueing + manual facilitation can act as a good treatment intervention early in the POC. Below is a basic video demonstrating diaphragmatic breathing: Here are 2 other good resources we found off Dr. E's website (The Manual Therapist) on breathing:

1. 5 Techniques to try with Diaphragmatic breathing 2. Assessment and Treatment for Diaphragmatic Breathing by: SPT Fred Charles Thanks Mike Reinold and Dr. E for the great posts!  We found this gem recently posted on the ilovephysicaltherapy blog by Stelios Kolomvounis. MIT OpenCourseWare offers over 2,100 courses, which can be selected by topic or department. There are not too many PT specific courses yet, but MIT offers a variety of other topics available to the public for free! Check it out at the link below: http://ocw.mit.edu/courses/find-by-department/

|

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed