- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

|

In physical therapy school, one of the things that we are taught to screen for is non-mechanical pain. This is theoretically linked to non-musculoskeletal origin. How do we identify non-mechanical pain? Typically, it is constant and unchanging with different positions. You would think that would be easy to identify, but upon encountering your patients, I'm sure you have learned that isn't exactly always the case. Upon learning how to implement repeated motions, a positive sign for good results is intermittent pain. These patients tend to respond extremely well to this treatment form. However, that doesn't mean constant pain won't respond. First of all, frequently patients who report their pain is constant don't necessarily understand that constant is associated with 24 hours a day 7 days a week. So make sure you clarify that first. Second, if a patient can find more comfortable or uncomfortable positions or activities that can help to identify the excessive loading pattern and directional preference. Now in some rare cases, a patient will continue to report a constant unchanging pain. I had this happen several days ago. This patient from the initial evaluation had a demeanor that was not interested in physical therapy and consistently stated her pain was unchanging, yet didn't really have much interest in pursuing physical therapy other than her doctor telling her to attend. I proceeded to assess repeated sideglides for her hip pain, using pain with walking as her asterisk sign. After about 60 repetitions, the pain had significantly reduced and my patient was in disbelief. While this patient did respond to repeated motions with her constant pain, that doesn't necessarily mean all constant pain will respond accordingly. It can be a red flag, but remember 1 red flag by itself doesn't necessitate referral. Make sure you really question your patients on the pattern of their pain and for any potential aggravating/alleviating factors. This will help to narrow down those who have pain of musculoskeletal origin. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

0 Comments

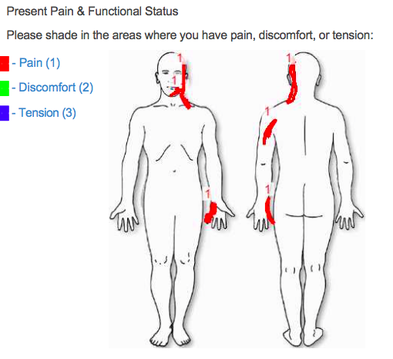

A patient recently presented to my cash-based clinic (Heafner Health) with the pain diagram seen above. The patient had a three-year history of left upper extremity pain that has been limiting almost all daily activities. From the picture alone, my first three clinical pathoanatomical hypothesis' were cervical radiculopathy, ulnar nerve peripheral neuropathy, or a double crush syndrome (thoracic outlet syndrome could be included in the double crush category). Additionally, due to the chronicity of his symptoms, I knew the patient would have some degree of central sensitization.

During the initial evaluation, he presented with the movement impairment syndrome of left scapular downward rotation and depression. Primary impairments included decreased left thoracic rotation, decreased scapular upward rotation, hypomobility in the CT junction and mid thoracic spine, poor serratus anterior and lower trapezius strength, and a positive ulnar nerve tension test. Additionally, the patient was unable to maintain cervical stability with any shoulder movement above 90 degrees. Following the objective examination, manual treatment included a supine thoracic manipulation, Grade IV CT junction mobilizations, IASTM to the left upper trapezius and scalene muscles, and active assistive sidelying scapular upward rotation. Following the OPTIM treatment paradigm, the manual interventions were followed with corrective exercises. These included seated upper trapezius shrugs (with arms resting on a pillow), serratus anterior presses with the shoulders at 90 degrees, and seated chin tucks with upper thoracic extension. We attempted ulnar nerve tensioners, but I did not feel comfortable prescribing them as part of his HEP. The patient was given education on chronic pain (told to watch ‘understanding pain is less than 5 minutes’ and the ‘Lorimer Mosely TEDx Talk’) and ergonomic set-up. Following the treatment session, the patient's upper limb tension test had improved by nearly 40 degrees. What other initial diagnoses were you suspecting based on the pain diagram? Anything else you would add to the initial treatment? -Jim Heafner PT, DPT, OCS  With any lumbar spine examination, lower extremity flexibility and mobility is assess as well. Part of the theory behind this lies in increasing the mobility in the surrounding joints in order to take the repetitive strain off of the spine. Another reason lies in the fact that the iliopsoas can act as a spinal compressor. Decreasing the activity in the muscle can theoretically take tension off the lumbar spine. With this presentation, we need to ask why these muscles are tight or why we see muscles "tighten up" in general. One instance where a muscle shortens can be due to an extended time in a shortened position. This is known more as a contracture. On the other hand, muscle can have increased resistance to stretch or stiffness. Why does this happen? According to Shirley Sahrmann's theory, with prolonged postures and repetitive movements, muscle imbalances develop that lead to varied passive tissue tension. The muscles with increased passive tissue tension present as "tight." But what if this tightness is secondary to hypertonicity with overactivity of the nervous system? We typically see restricted flexibility in lower extremity muscles in those with back stiffness and pain for a couple reasons. With restricted mobility along the path of a nerve, the nervous system no longer acts normally. Pain can be present, mobility can be restricted and muscles can be weak. Think double crush syndrome. Another possibility is that in a painful region like the lumbar spine, the muscles around might be tightening up to provide some level of stability throughout daily activities. Those that are consistent with retesting asterisk signs after treatment likely will have noticed at some point that we can change what appears to be muscle tightness by treating the lumbar spine, whether it be through manipulation, repeated motions, or core activation. The common variable is that we are affecting the nervous system. A common patient to associate this with is the one that can't touch their toes but immediately can place their hands flat after doing a few repeated motions. I wouldn't necessarily say that time spent stretching these stiff muscles is wasted but think about the patients (or yourself) that have repeatedly stretched a tight muscle with little lasting improvement. The theory of contract relax has to utilize the nervous system to reciprocally inhibit the muscle, as well. Given this discussion, I hope you will think again about how best to improve muscle flexibility in your next patient. I'm not saying stretching should be completely disregarded (I assign it still to help lock in gains and to satisfy patients who think they need stretches), but prioritize your treatments to more effectively lengthen the muscles and treat the source. -Chris

For today's post, I want to pose more of a question. One of the foundations of physical therapy training, as it typically takes place during the first year, is range of motion (ROM) measurement. ROM measurement involves using a goniometer (or landmarks) to assess the mobility of a joint. If you take a look at people around you, you'll likely see a significant variety in mobility at each joint for each person. But where do the ROM norms come from? As you look at different texts, you will find it difficult to find two different texts that have the same ROM degrees or landmarks in each of them. This doesn't necessarily answer the question about where ROM norms come from. They typically are averaged over a certain population. The issue with that is that here is significant variety in each population and the standard motions found may not necessarily accurately represent the true motion available. For example, consider the patient with only 10 degrees of lumbar motion (no pain) however following a set of repeated lumbar extensions, quadruples the mobility. There are many people that when measured "cold" will not demonstrate the normal mobility and they are asymptomatic. What are the odds that many of these people were used in a research study? I cannot say I have a certain answer, or that it is even worth seriously considering, but there are several possibilities or options. One is to base our standards off a younger population. Typically infants and young children are less likey to have developed compensations and restrictions, so maybe base our norms off them? A system like the Selective Functional Movement Assessment (SFMA) partially bases its standardized norms off these, but the most important part is to be consistent in your assessments. You will find norms from your experience, but also within each individual. I'm sure from your experience you have found that some patients are "hypermobile" and some are "stiff" throughout and exhibit a significant loss of motion everywhere. You want to take your measurements throughout the body and definitely compare side to side and with people in a similar population. While this method is not perfect, the most important factor is that you are consistent. What are your thoughts on this issue? -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

As many of our regular followers are likely aware, the progression of pain science research has revealed not just the fact that tissue pathology is not correlated with the pain experience, but also the impact of biopsychosocial factors. These factors can be from a variety of sources. A patient's home life, work concerns, cultural beliefs and more can impact how a patient experiences an injury. Recently, I was speaking with Dana Tew, PT, DPT, OCS, FAAOMPT of Optim Manual Therapy Fellowship about some new studies that came out. While the level of evidence is not as high as we would ideally like, their findings can still suggest some interesting things. One of the things many manual therapy classes teach is to educate your patients on how exercises can help them. A recent study on ultrasound showed that if the therapist positively described the benefits of ultrasound to the patient (compared to the controlled group of no education), then the patient exhibited an improved SLR! While no changes were found in pain, the fact that our words can potentially impact neural tension and mobility is impressive. Another study looked at a patient's expectations of physical therapy and their likelihood of success with physical therapy. It found that low expectations of physical therapy were more correlated with decision to undergo surgery than any anatomic features. I definitely can identify with this one as I have had some patients come in for physical therapy simply because they were told to by their doctor or insurance. Even with education and improvement with conservative treatment, these patients tend to pursue surgery. Regardless, the significant thing taken away from these studies is that the importance of the mind on our treatments appears to be reinforced. Not only can it impact pain, but also neural mobility and chance of success with PT. We should be certain to use these studies when educating our patients. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

I'm often asked what one can do to improve upon their resume in order to better their chances of getting into a residency. The fact of the matter is that it is extremely competitive. I thought I had an excellent resume, when I applied to various residencies. I had been a co-founder of this website, near perfect grades, excellent references, previous work in the field, and other items. That being said, I was only offered a couple spots out of the 6 residencies at which I interviewed. Now part of the failure can be attributed to a couple poor interviews, without a doubt, however, I am more than certain that there were things I could have done to improve upon my resume. The biggest recommendation I give to residency-hopefuls is to consider every opportunity presented to you. It can be difficult to pursue some of these opportunities. When you are in school, a night hanging out with friends sounds better than volunteering to help out at a basketball tournament. Doing some screens at a soccer practice after hours is not always appealing after working a 10-hour day. However, sometimes it is things like these that can lead to other ventures down the road. Doing a little extra at your work can lead to promotions, raises, or at least an excellent reference should you pursue another job. When I first started teaching physical therapy students, I was not paid for my time. However, it forced me to know the material even better, gain experience teaching, and I believe played a significant role in getting me where I am today. When Jim first approached me about starting this website during physical therapy school, I could easily have shrugged it off and thought it wasn't worth the time; however, I latched onto the opportunity and helped develop the website to have over 4,000 followers on facebook and nearly 50,000 views a week. Now I am not saying you need to accept every offer that comes your way, but absolutely consider it, especially if there is some higher goal to be reached. What I am advocating for is a form of long-term selfishness (some may call it selflessness). You will be presented opportunities that do not offer pay initially, but can lead to a job in the future, a payment down the road, networking, etc. These chances may have minimal short-term reward, but in the end can potentially help you reach your goal. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

|

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed