- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

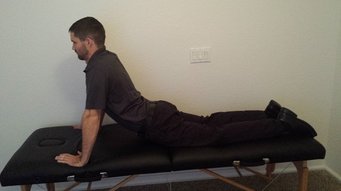

Over the last few months, I have incorporated repeated motions into my exams and treatments more and more frequently. In fact, I probably prefer using these techniques prior to my manual treatments. More often than not; however, they are used in conjunction. Repeated motions are an excellent way to sustain any changes you might get with your manual treatments. The key to repeated motions is getting to end-range. With lumbar complaints, the majority of the time the patients will respond to repeated extension, either bilaterally or unilaterally. Typically, unilateral complaints respond to repeated sideglides (extension on involved side) and bilateral complaints respond to lumbar extension. There are a couple different ways to get to end-range: in a loaded position and an unloaded position. For extension, the options are standing lumbar extension and prone press-ups. In the past, the reason why I would choose loaded versus unloaded repeated motions was patient irritability. If a patient was unable to complete the loaded repeated motion due to irritability, an unloaded motion may be permitted as the tissues aren't as sensitive. Recently, I discovered another reason for switching to prone press-ups versus standing extensions. I had several patients that had reduction in symptoms with repeated standing extensions, but their symptom reduction plateaued. Upon examination of their technique with the backwards bending, I realized they were unable to get to end-range as the majority of motion was coming from the hips, even when using a table to block the thighs. I then reassessed the repeated motions with prone press-ups and the patients had significantly greater range and reduction in symptoms with the press-ups. This is a perfect example of a motor control issue that limits end-range. It can also be useful for patients with unilateral losses of extension. By shifting the shoulders to the involved side, prone press-ups can bias the side that has a loss of loading. If you find your patient's plateauing with upright repeated motions, try switching to a position that isolates the motion and allows end-range to be reached. -Chris

7 Comments

Have you ever wondered why a patient's muscles tend to spasm in the presence of injury? The answer lies in the alpha-gamma loop. For example, the other day I was performing PROM on a post-surgical rotator cuff repair patient. During the treatment, noticeable muscle spasms were occurring in several muscles surrounding the glenohumeral joint. In the alpha-gamma loop, sensory neurons, which provide information about length and tension of muscle fibers, send signals to the alpha motor neuron (AMN) located in the brainstem and spinal cord. The AMN sends the signal to the motor cortex. Finally, the signal is sent back to the muscle resulting in a muscle contraction. In normal healthy movement, the loop is uninterrupted. When the body is injured, the gamma loop can become imbalanced. Sensory cells within the muscle spindles do not know how to interpret the input. The signal sends an improper impulse toward the brain and spinal cord. Since the impulse is abnormal, the alpha motor neuron also misinterprets the information. The efferent response, which would be a muscle contraction, is now a muscle spasm. Check out the quick YouTube video below for more information! A couple weeks ago I had to do a progress note on another PT's patient (something I don't enjoy). Typically I just re-take the measurements and continue with the treatment, but if a significant lack of progress has been noticed, I may adjust the plan of care. It is not an easy task or decision to make, changing a treatment plan, but we must look out for the patient, especially if we notice something is missing that is essential to the care. There are various ways you can accomplish this. You can speak with the regular PT about your findings with recommendations, include your findings and recommendations in the note (if you are unable to speak to the PT before the next treatment session), or sometimes adjust the plan right there...CONTINUE READING..

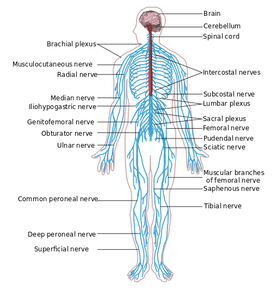

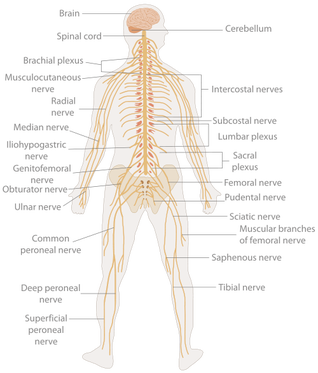

We recently had our second Fellowship class which focused on joint manipulation and adverse neural tissue tension. As you may have noticed with the recent increase in posts related to the neural system, the class had quite the impact on us. The obvious benefit the manipulation portion of the course was a dramatic improvement in our technique and clinical reasoning behind when and where to do a manipulation. As beneficial as that was, the part of the course focusing on neural tension had an even greater impact...CONTINUE READING

Recently, OPTIM Manual Therapy Fellowship wrote a response blog post to a Move Forward PT podcast entitled: "Could that Pain be Unhealthy Fascia." It appears that OPTIM was not the only group of individuals upset by this segment. The APTA removed that segment from the Move Forward PT website after backlash from a number of individuals. In short, the segment discusses fascia, how it is injured, and how the fascia can inhibit movement. This post is not to meant to criticize the podcast (that has been done by many others before me), but bring light to other issues and concepts surrounding the podcast. First, I agree with the OPTIM PT response. When assessing patients with musculoskeletal dysfunction, one must go to the joint level first. This statement transcends fascia. It applies to muscles, nerves, and other connective tissues as well. For example, if the IT band is causing a friction syndrome, go to the levels that innervate the TFL. If an individual has a positive Thomas Test for two-joint shortness, assess L2-L4 for dysfunction. A novice clinician might only treat the tight rectus muscle with stretching or a tight IT band with a foam roller. Typically, this does not treat the cause of the dysfunction. In many instances, assessing the joint will lead you to the cause of the dysfunction. Go to the joint level before going to the tissue! Second, in the podcast the interviewee, who is a PT, DPT, OCS, discusses using the foam roller as an initial line of treatment for patient's with IT band pain. If the foam roll does not correct the problem, the individual should then go see a physical therapist. Why is it not the other way around? The patient should first go see a PT who can properly diagnose the problem. As a profession we need to stop promoting passive modalities to take the place of our job. If we ever expect to advance in the medical world, we need to promote ourselves as the first line of defense in musculoskeletal dysfunction. Finally, having a specialty certification does not automatically place your above and beyond your colleagues (sad to say since I am currently studying for my OCS). In the segment, the PT is also an OCS. Despite having these initials, she is still discussing the fascia as a cause of the problem and administering foam rollers for treatment for IT band pain. Simply having a specialty certification is not enough, we must stay on top of the literature and learn advanced treatments in order to practice with the highest quality care. To check out OPTIM's response click HERE To learn Advanced Techniques, join our premium page: HERE -Jim Recently a patient with low back pain also had complaints of UE symptoms. She had awakened that morning with burning in her L lateral 3 finger tips. Even though I was seeing her for her back, I quickly looked at her UE symptoms in order to give the patient some information about the impairments. Since she had neural complaints in her lateral 3 fingers, I thought it would be wise to assess neural tension of the median nerve. Upon placing the limb in a partially tensioned position, the patient exhibited clonus of elbow flexion. Questioning myself, I took the patient out of the tensioning position and immediately did rapid elbow extension without any resistance. Placing the limb back into the median nerve tensioned position slowly resulted in clonus again. This lead me to do a slightly more thorough neuromuscular screening. The patient had a history of decreased sensation on the R side and had seen a neurologist 5 years ago, which resulted in negative EMG studies. The patient denied any constitutional symptoms and had negative gait ataxia, Hoffman's, slump test and Inverted Supinator Sign. On the R side, she did present with some odd neuromuscular signs. With Babinski, she reacted with involuntary hip flexion on the R while L side was negative. With tensioning of the R median nerve, the patient rolled out of the tensioned position involuntarily. She was hyperreflexive on the R side as well. Due to this atypical presentation, I referred the patient to a neurologist. Afterwards I consulted with several physical therapist, including my mentor, all of whom had never heard of clonus with a neural tension test. The reason I present this patient encounter is to review the essential components of a neuromuscular screening. Due to the fast pace of the clinic and the fact I was seeing her for her back, I was unable to do a thorough exam. Below I will include all things I should have looked at:

-Dermatomes: looking for altered sensation along different spinal levels -Myotomes: looking for weakness along different spinal levels -Reflexes: looking for either hyporeflexia (Lower Motor Neuron lesion) or hyperreflexia (Upper Motor Neuron lesion) -Cluster for Cervical Myelopathy: -Gait Ataxia -Babinski -Inverted Supinator Sign -Hoffman's Sign -Age >45 -Slump Test and SLR: tensioning of the neural system from the LE -ULNT's: tensioning of the neural system from the UE -Clonus: looking for potential Upper Motor Neuron lesion -S&S: -NIght Pain -S&S of Cauda Equina Syndrome -Bowel &Bladder Changes -Nausea & Vomiting -Significant Changes in Weight in Last 6 Months -Fever -Hx of Cancer -Unusual Fatigue -Tolerance to Heat and Cold The above list is many of the aspects one needs to consider in your neuromuscular examination. Our normal exams will also look for spinal and peripheral joint mobility and the joint's response to repeated loading. However, when concerned about a potential neuromuscular disease, we should be aware of the accumulation of these S&S. For example, with this patient's young age (20), history of decreased sensation on one side, difficulties with heat/cold, and odd reactions with neural tensioning diagnoses such as multiple sclerosis come to mind. It is for this reason that it is essential we screen our patients thoroughly for systemic conditions of all types. What other exam measures do you include in your neuromuscular screening? -Chris  Overview The ANS is comprised of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. In physical therapy school, I was taught to look at the autonomic nervous system (ANS) as an up or down -regulator of homeostatic function. Its functions include pupil dilation, gut mobility, force of cardiac contractions, and much more. Early into my clinical practice as an Orthopedic Manual Physical Therapist, I did not perceive the connection between the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the musculoskeletal system. Entrapment of the sympathetic nervous system can be a contributing factor in anything from peripheral nerve pathology to chronic regional pain syndrome. Understanding the different components of the sympathetic chain can lead to better treatment strategies. Anatomy & Function The sympathetic nervous system lies just anterior to the costotransverse joints from T1-T12. Each region of the sympathetic nervous system corresponds with a region of the body. T3-T7 innervates the upper extremities, T7-T12 innervates the lower extremities, and the entire chain (T1-T12) innervates the trunk. In a healthy population, normal mobility exists in the SNS allowing information to flow uninterrupted. In the presence of chronic pain, the spinal inter-neurons may become more sensitive to stimuli. This phenomenon is known as central sensitization. The patient may develop hyperalgesia, allodynia, and have decreased pain thresholds. These symptoms are due to SNS dysfunction and can manifest in our musculoskeletal patients. No one understands the exact interaction between the sympathetic nervous system and pain, but we know there is a relationship. By altering the function of one, we can change the function of the other. Treatment Patients who present with central sensitization can benefit from manual therapy. Since we know that each region of the SNS corresponds with a body region, manipulation or mobilization should be directed accordingly. A patient with hyperalgesia of the upper extremity will better benefit from a manipulation of the upper thoracic vertebrae. Contrarily, those with pain alterations of the lower extremity will benefit from a manipulation of the lower thoracic vertebrae. If the patient presents with CRPS, the patient may not tolerate the force of manipulation. Joint mobilizations of the respective area will suffice. As therapists, people often need proper "validation" for performing a manipulation. Thoracic manipulations are very safe and mobilizing the SNS can help increase the pain threshold to provide a window of opportunity to maximize the effects of your treatment. -Jim |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed