- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

|

I've written before about the potential need to address "muscle strains" with a neural perspective. Earlier this week one of my co-workers was doing a single-leg squat when he immediately felt intense and sharp upper inner thigh and upper posterior thigh pain. As a result, he displayed a significant antalgic gait pattern. I was busy that day, so I didn't get to look at him, but I, of course, suspected the potential spinal contribution. The next day my co-worker came to me and told me when he tried doing a lunge the previous day his pain switched sides! If that doesn't tell you to look at the spine, I don't know what should. While he was feeling and walking a little better, my co-worker asked me to take a look at him at lunch. Objective Multisegmental Flexion: Slightly Dysfunctional Nonpainful Multisegmental Extension: Significantly Dysfunctional Nonpainful Multisegmental Rotation: Dysfunctional Nonpainful bilat Deep Squat: Dysfunctional Painful Sideglides in Standing: No significant asymmetry noted HS Flexibility: WNL Mild loss of hip flexion mobility bilaterally with reports of "tightness" in posterior hip Hip IR/ER ROM: WNL At this point, the most significant findings are the loss of lumbar extension and hip flexion. While I could have tried tensioning either the obturator or sciatic nerves, I was pretty certain the pain would respond to lumbar treatment. I had my co-worker perform a deep squat as his asterisk sign. My co-worker then performed 20 repetitions of prone press-ups with manual overpressure to the lumbar spine, followed by a reassessment of the deep squat. He reported a significant reduction in pain. Following an additional 20 repetitions, he had no pain with a deep squat and it became functional. I reassessed his lumbar extension and hip flexion mobility and some limitation remained. At that point, I did a lumbar manipulation bilaterally and hip distraction manipulation bilaterally to help normalize his lumbar and hip motion. His HEP was repeated press-ups and hip flexion. There are a couple take-away points from this one. Always always always check spine. With "weird" symptoms, like switching sides, something neural is likely suspected, even if there is no lumbar pain. Also, in all our patients coming in with "muscle strains," perhaps we should be checking for neural components and trying to treat the spine as well. Both muscles strains and neural tension can present with a sharp and acute pain, so we must be sure to differentiate and treat appropriately. -Chris

Like this post? Then check out the Insider Access Page for advanced content! And check out similar posts below!

2 Comments

In last weeks post, I wrote an article about being a PT in a busy clinic. A portion of the post discussed simplifying one's treatment session by being efficient in the clinic. I briefly mentioned a few shortcuts I take during my examination to minimize my objective testing. Disclaimer: I understand people may not agree 100% with every point. They should be used as a guideline. In addition to the shortcuts, I use clinical reasoning and individual patient presentation to guide my plan of care. In the end I care most about decreasing pain and improving movement quality.  Clinical Shortcuts: 1. Heel Walk and Toe Walk vs. full dermatome and myotome screening. I do not perform a full neurological screening on all low back pain patients. If a patient presents with low back pain without radicular symptoms, I will quickly assess myotome strength by watching them heel walk and toe walk. This assessment shows L4 and S1 strength while assessing general balance. I generally perform this screening immediately after watching their gait pattern. If they have any difficulty performing the movements, I break out a full neuro screen. 2. Squat/SL squat vs. gluteus medius testing. While the MMT for gluteus medius strength is preferred, when I am busy, I quickly look at overall function first. If the patient's lower extremity moves into adduction and internal rotation during the squat, I know the strength or motor control of the glut med is not adequate. This assessment provides me with the rationale to prescribe glut strengthening exercises. 3. CT junction hump vs. CT segmental mobility assessment. If a patient presents with a dowagers hump, I immediately know they have mobility deficits in the CTJ and upper thoracic spine. The CTJ is extremely important for normal shoulder, cervical, and thoracic mechanics. If this postural hump is present, I know CTJ will be a top region of focus. 4. Thoracic kyphosis vs. testing low trapezius strength. Thoracic kyphosis and shoulder dysfunction go hand-in-hand. When someone has increased thoracic kyphosis, the mid scapular muscles are placed in a lengthened position. In general, lengthened muscles are also inhibited. I can immediately infer that someone with increased thoracic kyphosis needs lower trapezius and middle trapezius strengthening. Always strengthen the lengthened muscle before stretching the shortened structure! I discuss these concepts and more in my 2017 ebook, The Guide to Efficient Physical Therapy Examination! -Jim We have previously discussed the issues with the pathoanatomical approach in regards to assessment or treatment, however, occasionally it can be of use. Due to the potential benefits, I advocate for a gross motion assessment/treatment followed by segmental assessment/treatment if necessary. With the cervical spine, I typically use segmental sideglides to identify a local restriction. While it can be an efficient way to identify segmental restrictions into either flexion or extension, it can offer conflicting results if a restriction is located in the uncovertebral joints. The uncovertebral joints are located between C3-T1 and are made up of the uncinate processes above and below each vertebra. They are one of the first locations of degeneration in the cervical spine and can significantly restrict cervical sidebend. One of the primary signs of uncovertebral joint involvement is relatively normal rotation, flexion, and extension, but significantly restricted sidebend. In cases like these, segmental sideglide assessment should still be used to identify a restricted region, but then follow it up with segmental flexion/extension assessment of each facet. With a true uncovertebral joint restriction, we'll note normal flexion and extension segmental mobility on each facet but hypomobile sideglides. Were you to try utilizing mobilizations/manipulation/MET's to address flexion/extension restrictions at the facet joint, you likely would notice some improvement but still have pain and restriction remaining. Treatment of the uncovertebral joints requires a gapping mobilization/manipulation of the segment. I typically use the lateral break technique (coming soon on the Insider Access Page!). Are there other methods that can address this dysfunction? Absolutely. While a manual technique is quick and effective, the patient can lock in the changes and treat themselves with repeated motions. Due to this being a unilateral issue, it likely will respond best to repeated cervical retraction with sidebend. The issue, as always, is with patient compliance and communication. For success, a patient has to be able to communicate exactly what they are feeling with the exercise and then be compliant with the prescribed frequency. Regardless, the uncovertebral joints should be considered in your patients with painful and limited sidebend. -Chris

Like this post? Then check out the Insider Access Page for advanced content! And check out similar posts below!

Last week in our OPTIM online mentoring session, the question was asked about how to provide great care while managing 2-4 patients at a time. If you see a high volume of patients per day, is it possible to practice evidenced based medicine? If so, what are some implementable strategies to managing multiple patients?  The quick answer is 'Yes.' It is possible to be busy and effective at the same time.' With that said, succeeding in this environment is difficult and often leads to professional burnout. In order to succeed in a busy clinic, you must be efficient in your history and examination. Efficiency is recognizing patient movement and behavior patterns and minimizing your objective testing according to these patterns. There is no time for irrelevant tests and measure. The clinician should only perform pertinent positive and negative tests. For example, if you treat an individual with a history of non-specific mechanical back pain for the past 10 years, the physical examination will not point to one specific structure. From a musculoskeletal standpoint, all structures have healed. The patient now has chronic pain with central sensitization. A more general strengthening and conditioning program may be more appropriate early in the plan of care. Additionally, choosing how to classify patients should come from the intake paperwork and subjective history. You should gather ~80% of the information during this portion of the evaluation. A second strategy for success in a busy clinic is SIMPLIFYING your treatment plan. Dana Tew, OPTIM president, often relates various PT diagnosis' to treating the common cold. When you go to your PCP for the common cold, do you want a new, innovative treatment OR do you want the gold standard for treating a common cold? The answer is simple, the gold standard. For example If a patient presents with low back pain with mobility deficits, they likely need a lumbar manipulation followed by mobility exercises and hip strengthening. There are high levels of evidence to support manipulation for acute low back pain, but many PT's are still not performing these techniques. In addition to simplifying the manual treatment, simplify your exercise routine as well. It may be tempting to choose a fancy, new Youtube exercise, but you should choose consistent progressions that are evidenced based. In conclusion, continually reflect on strategies to be more efficient during your examination and work on methods to simplify your treatment progressions. OPTIM discusses these components in our COMT and Fellowship courses because these components determine if you are practice at a novice or expert level. Let me know if you have other strategies for being effective in a busy clinic! Jim  A couple weeks ago I wrote an article about the link between Double Crush Syndrome and smoking. I received some feedback that made me want to return to a particular subject. In case you missed it, due to the link between smoking and decreased oxygenation of various body tissues, smoking (and similar co-morbidities) can affect neural conduction and, thus, contribute to Double Crush Syndrome. The topic that was brought up primarily surrounded medical marijuana. Medical marijuana is used by some for pain relief, among other reasons. So what about the discrepancy between these uses and potential contribution to Double Crush Syndrome? With the progress in pain science, one thing that we should understand at this point is the power of the mind. I've spoken before about how placebo can impact a patient, due to patient beliefs. The same can apply to any treatment. Getting back to medical marijuana, there will be some patients that have success with the drug lowering the sensitivity of the nervous system and decreasing pain. For some people it won't work. As ambiguous as that sounds, we should still try and at least use evidence to guide our decisions. We should remember the physiological response of our bodies to smoking. With smoking, one of the body's responses involves vasoconstriction and increased blood pressure. This results in decreased oxygenation of the tissues throughout the body and potential neural tension. We must remember, however, that there are nerves that descend from the CNS that can alter the sensitivity of the afferent nerves. So if someone is believing they will have a positive effect from smoking, they may benefit from not eliminating it immediately. So how do we handle this as clinicians? On one hand, we know there is a link between smoking and cancer, so we should educate our patients on the dangers of continuing smoking. On the other hand, if we tell a patient to stop smoking immediately, they may ignore any advice we give and fail to improve. What I would recommend is educate your patients on the physiological effects of smoking and the benefits of quitting. Do not demand your patients stop, but encourage weaning off of it to not only improve their pain, but their health overall. The patient may have a period where they get pain relief from smoking or marijuana, but either offer alternatives to stress/pain relief or use a period of pain relief to progress the patient beyond the need for smoking. -Chris

Like this post? Then check out the Insider Access Page for advanced content! And check out similar posts below!

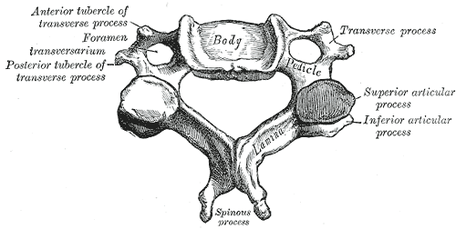

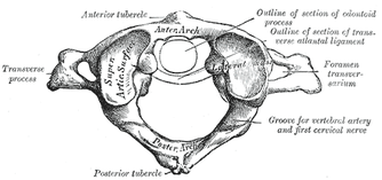

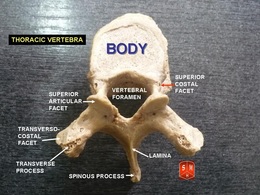

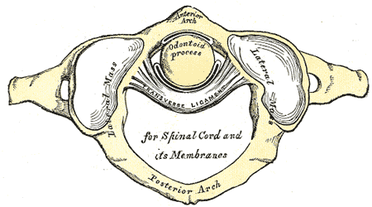

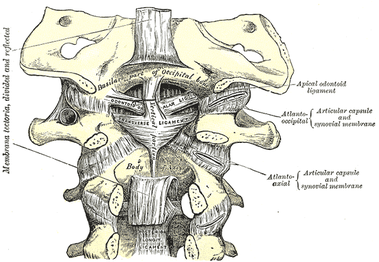

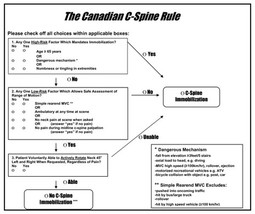

At our last OPTIM COMT Course, I gave two separate lectures on tissue mechanics and patient education. While seemingly unrelated at first, when preparing the lecture I discovered how interconnected the two topics are. For example, understanding basic tissue mechanics (collagen synthesis, healing time frames, etc...) has a direct connection into the patient's prognosis and plan of care. This post is about how we can turn our in-depth anatomical knowledge into patient friendly education. Essentially, how can we sell exercise to our clients! First and foremost, as physical therapists, we must understand we are selling something people struggle to buy. Exercise is hard work! It takes effort and commitment. It takes a life change. Before selling exercise, the PT needs to determine if the patient (customer) is ready to buy. From my experiences, many patients are truly ready for change or at least capable of persuasion. Once we confirm the patient is appropriate for therapy, then we can really delve into treatment and education. The Science On the physiological level, the body undergoes three phases of tissue healing: inflammation, proliferation, and maturation. Inflammation lasts 48-72 hours. In this phase the cells have an influx of white blood cells and fibroblasts to help facilitate healing and decrease waste products in the cell. As healing progresses the cells continue to develop and repair in the remodeling and maturation phases. Collagen synthesis occurs for up to 1-2 years meaning the injury may take longer than the patient anticipates. (See previous post regarding Expectations and Time Frame of PT.)  The Proper Education Since we know the body will undergo three phases of healing, we need to provide appropriate education to make these changes occur as efficiently as possible. There are several factors that influence collagen remodeling: adequate blood supply and oxygen, movement, pharmacology, protein intake and vitamin C intake. In physical therapy terminology, exercise aligns the collagen fibers, provides cellular lubrication, and increases elasticity of the tissue. In patient friendly language, we can explain the importance of gentle movement early will decrease swelling, increase blood flow to the region, and allow the tissue to remodel appropriately. Protein and vitamin C directly effect collagen strength and fibroblast production. Proper nutrition following an injury will give the injured tissue the greatest chance for healing. Simple education points like the ones above can make selling your treatment sessions much easier. Do not be ashamed to think of yourself as a salesperson because we are in the health care field! -Jim Something that should be included in every upper quarter evaluation, especially following a MVA, is ligament integrity testing. As physical therapy moves towards primary care, we must be certain we screen our patients for any potential instability or hypermobility in the cervical spine that may impact the patient. In general, you want to check both the transverse and alar ligaments both for integrity and laxity. With integrity deficits, the patient must be referred back immediately. With laxity, we may just choose not to utilize certain manual therapy techniques like manipulation. Anatomy The transverse ligament attaches at the medial side of each large, lateral process of the atlas with the anterior side of the middle part touching the odontoid process. The transverse ligament is responsible for maintaining the space of the vertebral canal by preventing the atlas from translating anterior relative to the dens. When damaged, the atlas slides anteriorly, impinging upon the spinal cord. There are two alar ligaments. The distal portion of each attaches to the respective sides of the odontoid process of C2. The proximal portion attaches to the tubercle on the medial side of the respective occipital condyle. When the head rotates or sidebends one direction, the tension in both alar ligaments (especially the contralateral one) is responsible for the spinous process of C2 moving the opposite direction. Performing the Tests Supine Transverse Ligament Stress Test: Place one hand on the occiput with the index finger on the space between C2 spinous process and occipital protuberance (where the posterior arch of C1 lies). Place the other hand on the forehead. Lift the head straight up in a vertical plane (not flexion, more of a protraction motion). The test is positive if the patient experiences some feelings of weakness, dizziness, numbness, nystagmus, or an odd feeling in the back of the throat. There is normally a firm end-feel. You should also note immediate motion of C2 spinous process when PA is applied to C1 posterior tubercle. If there is a delay, there may be laxity present. It should be noted that pain, by itself, is not a positive finding. We are looking for the neurological symptoms or "lump in the throat." Sharp-Purser Test (for Transverse Ligament): The patient should perform a slight cervical nod. The examiner then places one hand on the forehead, while the other hand is placed on the spinous process of C2 (both arms should be parallel to the ground!). A posteriorly directed force is applied by the hand on the forehead, while the hand on the spinous process of C2 just stabilizes. There should be a firm end-feel. A positive test occurs if there is a sliding movement of the head or a decrease in symptoms (often neuro symptoms; “clunk” may occur). Pain is not a positive finding. Alar Ligament Test: Place one hand on the occiput and use the other hand to palpate the spinous process of C2. Laterally flex or rotate the head to one side; you should feel the spinous process move to the opposite side. Repeat on the other side. Absence of the spinous process moving to the opposite side may indicate alar ligament injury. If you block the spinous process of C2 from moving, you may stress the ligament, looking at laxity. You should encounter a firm end-feel in this case. Significant movement may indicate ligamentous injury. Pain is not a positive finding. These tests are not enough by themselves, but when incorporated with your other exam findings, are essential for screening patients for instability. The reason I wanted to discuss this topic was the fact that I had a patient recently who had no cervical imaging following an MVA but was "cleared" for PT by a physician, even though the patient met part of the Canadian C-spine rules. This patient in particular was referred back for imaging, especially due to the potential "clunk" felt during Sharp-Purser test. Additionally, while I indicated in all the tests that pain is not a positive finding for the ligament stress testing (we are looking for neurological findings), the presence of pain may potentially indicate a sprain of the ligament. Typically, it just represents a hyper-sensitization of the nervous system in that region, however. Unfortunately, some specialties of physicians lack sufficient orthopaedic knowledge and training. It is for this reason that we must be highly skilled with our screening, especially if we want to increase our direct access. -Chris Fox PT, DPT, OCS Check out our Insider Access Page for advanced content!Other Similar Posts: |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed