- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

|

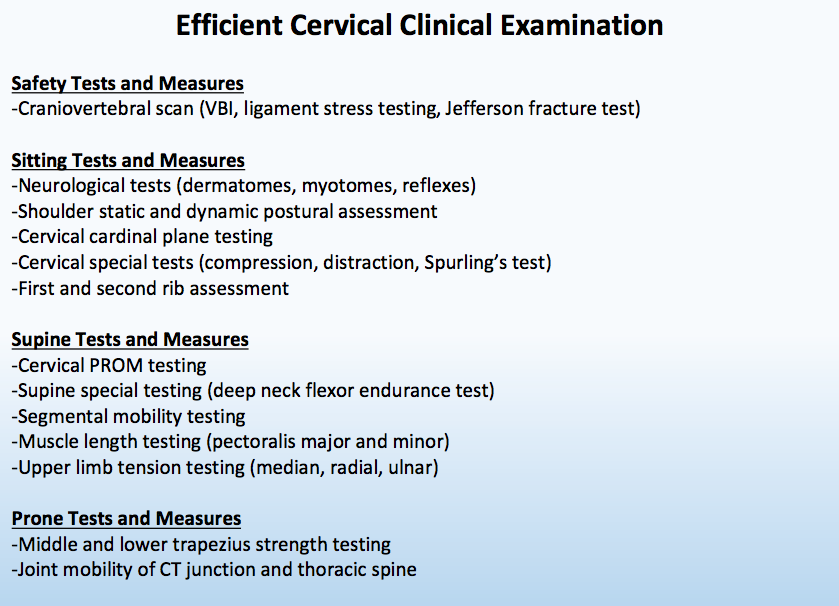

I distinctly remember the first few times I performed manual therapy on the cervical spine. My hands were sweatier than normal, and I had an unusual shakiness in my fingers. For some reason, I thought everyone with cervical pain was on the verge of having upper cervical instability. While this mindset was irrational, it may have been something that was instilled in me during physical therapy school. This fear was likely due to a lack of experience with the cervical examination and techniques. While performing a cervical spine examination may seem intimidating, it is very similar to any other body region. The main objectives should be to determine if the patient is appropriate for physical therapy and to identify the primary impairments that will have the greatest effect. The key to each evaluation is efficiently completing this process so that more time can be spent on treatment! In many instances, the examination begins in sitting following the subjective history. Depending on the subjective information, various safety tests and measures may need to be completed. While all safety tests may not be completed on every cervical evaluation, having them accessible is important. Assuming the patient is appropriate for physical therapy, many other tests can be performed in the seated posture to assist in making the appropriate physical therapy diagnosis. For example, shoulder active range of motion should be performed to determine if this region is a pain generator or contributing to the cervical pain. Additionally, a seated upper rib mobility assessment should be performed to determine if the ribcage is contributing the one's symptoms. The complete flow of tests and measures can be seen in the picture below. In the Efficient Examination breakout, many special tests are left off the list. Being efficient means quickly determining the painful region and identify primary impairments. The cervical examination should includes a brief assessment of the thoracic spine, cervical spine, ribcage, and upper quarter. Quickly assessing each one of these regions will help determine the true cause of the patient's symptoms. Do not be intimated by the cervical examination! Jim Heafner PT, DPT, OCS Follow Jim's Instagram Like this post? Last year Jim published 'The Guide to Efficient Physical Therapy Examination.' The Ebook takes readers through a step-by-step evaluation of the lumbar spine, cervical spine, knee, and shoulder. Each examination is centered around efficiency and clinical excellence.

1 Comment

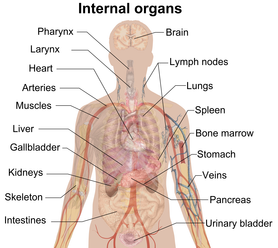

For those of you that follow TSPT regularly, I'm sure you are aware of my affinity for considering all 3 pillars of evidence-based practice (EBP) equally. With the push for a more research-driven approach, we are improving our foundation of what we know that works. This is excellent and should continue to be developed regularly. While it is a sign of progress, we need to remember an older phrase, "You know what you know, you know what you don't know, and you don't know what you don't know." With where research is going, we are improving our understanding of what we know and maybe even some understanding of what we don't know; however, I fear we are pushing so far away from the 3rd tier that we are purposefully blinding ourselves to it. In regards to knowing what we know, we know that strengthening the quadriceps and glutes in those with knee pain often helps. While we know that a thoracic manipulation does help with neck pain or shoulder pain, we don't necessarily know why. The mechanism is theorized under biomechanical, neurophysiological, or biopsychosocial. The issue lies in not knowing what we don't know. A perfect example of this is voodoo type treatments like visceral manipulation. The way it is presented in most physical therapy culture is as a joke, unfortunately. The lack of research and basic understanding tends to push many away from exploring the topic. With many never considering it as a possible beneficial treatment, they ignore any possible chance of discovering the potential benefits and effectiveness of the treatment. While I do think the concept would be more accepting if it had greater research support, I do not believe we have the techniques to fully study the methods. As I am preparing to take my first visceral manipulation course next week, I have been reading one of the textbooks for the course. A concept that was just brought up in the first couple pages was restriction in mobility of the viscera. The abdomen and thorax are typically ignored from a physical therapy education's perspective as we typically focus on muscles, bones, and joints. However, each time we bend or twist, there is force transmitted through the thorax and, thus, the organs. Is it possible that a restriction in visceral mobility can then limit motion or affect pain/disability as well? I do not know, but I look forward to developing some sort of understanding of it, so that I can at least begin to know more about what I don't know. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

Recently, Dr. Erson Religisio III over at Modern Manual Therapy discussed differentiating weakness versus inhibition in this post. If you take a look at the video, he finds that an inhibited muscle will test much stronger if we gradually increase resistance while applying force and the patient can then match, or at least improve. A truly weak muscle doesn't exhibit this improvement. When completing my residency, we found neurogenic weakness through repetition testing of the muscle. That is, we would quickly test the muscle strength and re-test the strength rapidly, looking for a loss of strength. While I think both Dr. E's method and the one I learned in my residency can play a role, personally, I look at any loss of muscle activity as potential neural involvement. What is key to consider is correlating with testing other muscles and other findings as well. For example, if the gluteus medius tests weak, as does EHL and peroneal longus/brevis, we should think about L5 being involved. The difficulty comes in differentiating peripheral nerve lesions from local muscular weakness, specifically if there are few muscles innervated via that peripheral nerve. In reality, with the power of the nervous system, I find that we can frequently alter "strength" through treating the spine or nerves. When in comes to practice, I recommend tackling it from all ends. If a patient with hip pain and weak glutes also has a deficit in lumbar mobility, I would treat both the weak glutes and limited lumbar motion. These are impairments and may or may not be contributing to the patient's dysfunction. As I always recommend, treat the impairments, but it may be fun to start playing around with testing for true weakness vs inhibition in your patients. See how that impacts your examination and treatment! -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

A few weeks ago, one of my colleagues developed some knee pain with running. He reported that it was "clicking" and had pain along lateral tibiofemoral joint line. Having review repeated motions in the past with him, I recommended what to assess and what likely was contributing to his pain (he also reported a history of LBP on and off L>R). Over the next couple weeks he would occasionally do his exercises, report some relief and then report that it "just wouldn't get better." Having finally gotten some free time in the clinic, I thought I would take a look at his knee. As many of you know, I always start at the spine in my evaluations. Even though a lot about this case screamed knee/meniscus, I still go to the spine. While flexion and extension of the lumbar spine were generally pretty good, he had a slight loss of loading L lumbar spine with sideglides. Additionally, he had loss of terminal knee ext and tibial IR mobility on the involved side. His primary report of frustration was that his knee felt "swollen/painful" with deep squats, so I made this my asterisk sign. With the difficulty loading the L lumbar spine, I had my colleague begin with 20 repetitions of press ups biasing the L side (I frequently go to this if it is an end-range deficit in mobility). I then reassessed the squat ("a little better"). Another 20 repetitions ("better"). Another 20 repetitions ("almost 100%"). At this point, I had found my colleague's directional preference. For fun, I re-checked terminal knee ext and tibial IR mobility at the end as well - both were nearly normal. While many think of repeated motions of the spine as possibly addressing pain distal to the spine, it also can have a significant impact on mobility of distal joints. If there's one thing to take from this case, it's to always check the spine! -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

Preferential activation of the vastus medialis head of the quadriceps is a trend that never seems to end. While I have talked previously in this post about the research for trying to activate the VMO, the concept was revisited by Chris Beardsley in this post recently but with more of a focus on alterations in squat forms. Changing the position of the ankles may improve quadriceps activation overall and the amount of activation does change throughout the depth of the squat; however, no study has been able to selectively activate the VMO. Check out these posts for a more in-depth analysis of the studies and their impact, but, overall, just focus on trying to strengthen the quadriceps muscle group as a whole instead of trying to isolate. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

|

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed