- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

“An estimated 1.6 to 3.8 million sports-related mild tramatic brain injuries (mTBI), also commonly referred to as concussions, occur each year in the United States.” The research on concussions has grown exponentially in the last decade. With better information, sports medicine professionals have been equipped with diagnosis and treatment of concussions. While it was once thought that complete rest for 7-10 days would clear up a concussion, we now know that some individuals sustain symptoms longer. We also have learned tools to better handle the post concussive symptoms and assist with treating these athletes. While concussions are typically not seen in the clinic, in team sports they are much more common. I’ve been fortunate to be side by side with athletic trainers on the field and basketball court for over 600 hours learning about concussions and other acute injuries. During this time I was lucky enough to see the many faces of a concussed athlete. Symptoms such as inability to articulate words, difficulty with memory, and a rash of different emotions were just a few of the symptoms that have stuck with me from some of the concussed athletes I helped off the field/court. Learning to recognize these symptoms was one challenge, but treating them post-concussion was a whole different. Treatment for concussions ranges. We know that intense exercise too soon can be detrimental to a post concussed athlete. Exercises targeting balance and proprioception are a must. Starting athletes out with simple balancing and progressing to ball tossing is a good start. Working on multi-directional lunge patterns or step-ups can be effective for neuromuscular control. Furthermore, dual tasking can be implemented to help with the cognitive function of a post concussed athlete. Dual tasking also serves the purpose of improving athlete performance as athletics often requires the combination of motor tasks and cognitive functions. Working an athlete in balance with a ball toss and reciting numbers or the alphabet is one example you can use to work dual tasking. You might be surprised how challenging this is in the beginning. Changing variables to progress the athlete is the goal. Moving from stable to unstable surfaces, adding a second ball, or tasking the athlete with a more complicated verbal recital are a few ways to progress. Just remember to continue slowly progressing cardio during this time. Treating concussions can be a challenge without the right information. Fortunately, we have lots of information and research available to us as sport clinicians. Sideline coverage is a great way to start learning how to recognize the many different faces of concussions. Treatment will vary athlete to athlete but dual tasking can be a very effective way to rehabilitate these athletes. -Dr. Brian Schwabe, PT, DPT, SCS, COMT, CSCS Board Certified Sports Physical Therapist

2 Comments

The Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) have been developed over the last decade with the goal of summarizing best practice methods for various orthopaedic diagnoses. While the utility of CPG's may be debatable, they do an excellent job providing a summary of the evidence for managing the specific conditions. With the hip being the focus of December, I am going to review what the evidence shows for examining a patient with hip osteoarthritis and the appropriate interventions. Before getting started, a quick reminder for the grading system for research: A (strong evidence), B (moderate evidence), C (weak evidence), F (expert opinion). Diagnosis (A): These patients are over the age of 50 and exhibit the following presentation (A-Level Evidence): -Moderate anterior or lateral hip pain with weight-bearing -Morning stiffness less than 1 hour after waking -Hip IR ROM < 24 deg or IR and Flexion < 15 deg compared to nonpainful side -Increased hip pain associated with passive hip IR Outcome Measures for Activity Limitation and Participation Restriction (A): -WOMAC -HOOS -LEFS -HHS Activity Limitation/Performance Measures (A): -6 Minute Walk Test -30 Second Chair Stand -Stair Measure -TUG Test -Self-Paced Walk -Timed SLS -4 Square Step Test -Step Test Balance Measures (A): -TUG Test -Berg Balance Test -Timed SLS Test Physical Impairment Measures (A): -FABER Test -Hip PROM -Hip Strength Testing As you can see, there are quite a few very reliable methods of diagnosing Hip OA and then tracking progress in function, balance, performance and impairment. It is in no way necessary to perform all of the above tests and measures. What I recommend from these is to identify your patient's goals and determine what outcome measures and performance measures will best track said progress. It is good to be thorough with the impairment measures in order to track objective changes. Once the patient has been diagnosed with Hip OA, there are several interventions that have shown varying levels of support. Interventions: -Education (B): activity modification, exercise, joint unloading, weight-loss -Functional Gait and Balance Training (C): gait/balance training and use of assistive device -Manual Therapy (A): thrust/non-thrust manipulation and STM and coupled with exercise -Flexibility/Strengthening/Endurance Exercises (A) -Modalities (B): US to ant/lat/post hip and coupled with exercises and heat -Bracing (F): should only be tried if exercise/manual therapy fail -Weight Loss (C) As you can see, the typical trend for PT continues with treatment for this diagnosis: manual therapy and exercise have high level evidence. While education has moderate evidence, it would be interesting to see the benefit of education that was more focused on pain science, graded exposure, and cognitive behavioral therapy. These topics are more pertinent today given the findings of pain science research, especially given how frequently people have "Hip OA" and don't have any pain. Additionally, it was surprising to see that ultrasound had moderate evidence. Even so, I would recommend more focus be placed on exercise, education and manual therapy for these patients. As a whole, I think that the development of CPG's will help to improve the standard of care. There is far too much varied care due to misdiagnosis. That being said, patients don't present "standardized" and we are moving away from pathoanatomical diagnoses as well. Hip osteoarthritis is so common in people that it is almost surprising that it even has its own CPG. There are so many factors that go into a patient's pain and disability experience: financial situation, relationship stress, past experiences, fear, and more. No two patients present the same. I recommend take the recommendations from the CPG into consideration, but don't hesitate to modify your plan of care based on the patient presentation. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS

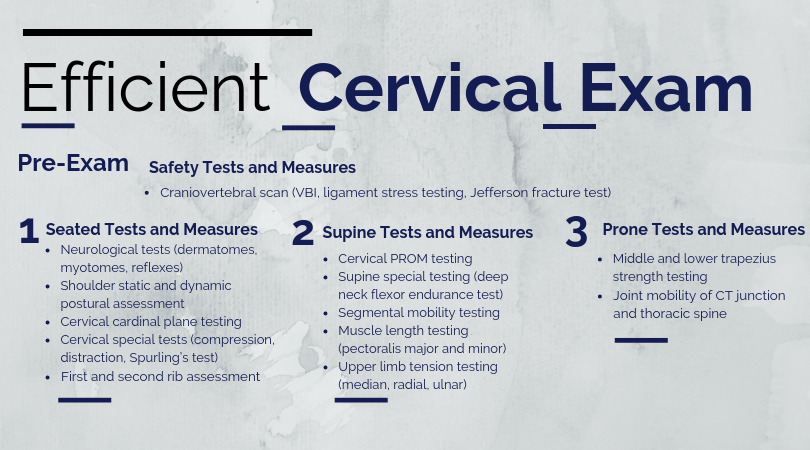

The Cervical Spine is Not Scary!The cervical spine is a sensitive region relative to other parts of the body; however, you should not be scared or less confident performing an evaluation in this region! When performing a cervical examination, it is important to assess for vertebral artery dysfunction, upper cervical instability, and other non-musculoskeletal pathology. Once you have cleared these regional red flags, proceed as you would with any examination. The KEY to creating a reliable cervical examination is to follow the same general steps for every new cervical evaluation you perform. These tests and measures are performed in a systematic, reproducible manner. While the clinician may add or remove testing as needed, the general framework for formulating their diagnosis is consistent. This consistency allows for efficiency and reproducibility. Cervical Examination Main Points

Cervical Examination SequenceCervical Day 1 Interventions (Post-Evaluation)Similar to my shoulder evaluation post and lumbar evaluation post, my Day 1 cervical interventions heavily focus on desensitizing the painful tissue through graded tissue exposure. Additionally, I spend a significant amount of time educating the patient on pain science and specific postures to temporarily limit due to pain. Cat/ CowCues and Main Focus Points

Thoracic Extension over Foam RollerCues and Main Focus Points

Many physical therapists are hesitant to perform a cervical spine evaluation due to a lack of confidence. Do NOT be one of them! Practice and perform the mental repetitions required to consistent and confident during your cervical examination. -Jim Heafner PT, DPT, OCS

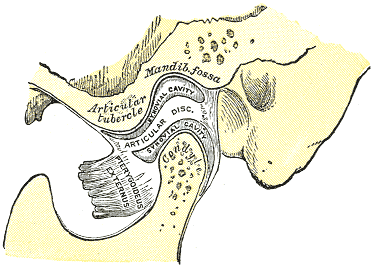

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is one of the least commonly treated regions of the body in outpatient orthopaedics. Due to this infrequency, many will therapists simply refer out to specialists when these patients present. Many are unaware of the fact that the TMJ and cervical spine are connected by more than just proximity. The spinal nucleus of the trigeminal nerve travels down into the upper cervical spine. Because of this relation, dysfunction (even if non-painful) in one can contribute to dysfunction in another. For this reason, among others the TMJ should be considered in management of cervical conditions and vice versa. One general point to consider regarding TMJ arthrokinematics is that movement of the mandible requires motion in bilateral TMJ's. A restriction in one may force a relative hypermobility in the other. The arthrokinematics of the TMJ require both rotation and translation. Rotation occurs between the superior aspect of the mandibular condyle and the inferior articular disc. Translation occurs as the condyle and disc move on the mandibular fossa/articular eminence. Protrusion/Retrusion: Relative anterior/posterior translation of disc and condyle on mandibular fossa/articular eminence. The mandible and condyle follow the slope of the articular eminence during the motion, so during protrusion, the mandible slide anteriorly and inferiorly. The opposite is true for retrusion. Lateral Excursion: Side to side translation of the disc and condyle on the fossa. The ipsilateral condyle has minimal motion, while the contralateral condyle moves anteriorly and medially. The ipsilateral condyle almost acts as a pivot point. Depression: Made up of two phases. During the early phase (35-50%), the condyle rolls posteriorly on the inferior surface of the disc with slight anterior translation. During the late phase (final 50-65%), it transitions to motion primarily consisting of condyle and disc translating anteriorly on the mandibular fossa and articular eminence. The roll and translation occur with varying degrees but the disc stays between the condyle and eminence to minimize stress between the structures. Protrusion and depression are limited by retrodiskal laminae being stretched by attachment to the disc. Elevation: The opposite arthrokinematics of depression. Elevation is initiated by tension in the retrodiskal laminae.

When you are assessing an individual referred for TMD and cervicalgia, your examination should include both (along with the rest of the upper quarter). Some standard examination techniques include are ROM, resisted isometrics, segmental mobility, palpation, listening for joint sounds (disc displacement), cotton roll test, and posture. ROM of the TMJ can reveal potential limitations of the capsule. Normal ROM is: 45 mm for depression, lateral excursion is 1/4 of depression, protrusion is 6-9 mm and retrusion is 3 mm (Ho, 2011). Lateral deviation to one side may signify capsular restrictions ipsilaterally, potential muscle dysfunction, or an anteriorly displaced disc without reduction ipsilaterally. This may be represented as a "C-curve" when opening (an "S-curve" is associated with hypermobility). Resisted isometrics can help you to identify a particular muscle that is not functioning properly. Segmental mobility of both the TMJ and upper cervical spine can potentially assist in identifying hyper- or hypomobility in a segment related to the abnormal mechanics. Palpation can be useful for assessing trigger points or tenderness in a capsule. The cotton roll test can help differentiate between muscular and joint involvement. If a patient complains of pain when chewing on one side of the mouth, have the patient bite down on a cotton roll. By doing so, this gaps the ipsilateral TMJ. Thus, if pain is decreased, it would appear the pain is joint related, but if it doesn't change or increases, the pain is muscular (it is still possible that the pain is related to the cervical spine as well). Also, we cannot forget about the cervical posture. Knowing the resting position of the teeth is important to understand the individual's TMJ mechanics and as previously mentioned the impact cervical posture can have on the TMJ. Finally, be sure to check for any poor habits such as bruxism, chewing on ice, grinding teeth, etc. that impact the TMJ. There are three primary disorders of the temporomandibular joint. Anterior disc displacement with reduction occurs when the disc rests anterior to the condyle. During depression of the mandible, the disc slides into proper position throughout the motion, but as the mandible elevates it slides into its anterior position again. Both of these disc transitions typically are accompanied by a "click." Anterior disc displacement without reduction occurs when the disc rests anterior to the condyle but is unable to slide into proper position during jaw movements. There is typically no clicking occurring with this pathology and depression of the mandible is limited (blocking translation of the condyle). Posterior disc displacement occurs when the jaw has been held widely open for a prolonged period of time or extensive range and the disc gets "stuck" posterior to the condyle, blocking mandibular elevation. With reduction, a closing "click" may occur. While this article by no means serves as a "how-to" with managing the temporomandibular joint, it will hopefully help to understand the biomechanics of the TMJ and some general concepts regarding TMJ pathology. It is essential to at least consider assessing the TMJ in cervical patients, particularly if their progress is limited. Unfortunately, the research for TMJ management is rather limited at this time. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS Check out our Insider Access Page!

|

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed