- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

|

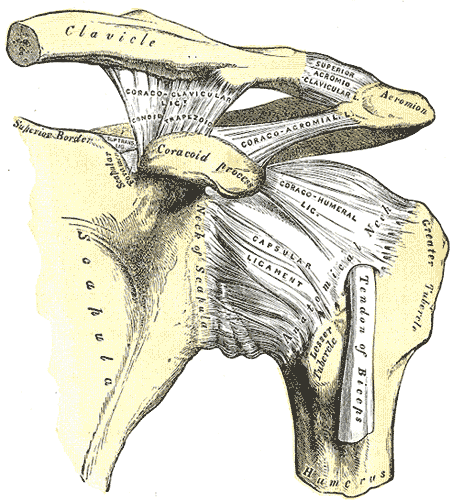

A couple months ago, we posted about the diagnosis and management of Lumbar Extension-Rotation Syndrome. The use of Shirley Sahrmann's Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes text can be extremely useful in identifying the original fault in a patient's injury. Some of the more common shoulder pathologies, like shoulder impingement and rotator cuff tears, actually can result from a movement impairment syndrome. Recently, I have come across a couple patients that did not present like the typical subacromial impingement or rotator cuff tear. After looking at the patient's movement patterns, I recognized a link between the impairments and dysfunction of superior humeral glide syndrome, leading to the proper treatment.

Alignment: -Flattened deltoids -Arms in abduction relative to scapulae. Associated with downwardly rotated scapulae. When scapula position corrected, humerus is in abduction. -Hypertrophied deltoid Movement Impairment: -During GH flexion or abduction, note excessive movement of head of humerus superiorly against acromion. More evident in abduction. -Humeral superior glide more evident during active abduction versus passive. -Decreased GH crease noted just distal to acromion with arm overhead. Impairments: -Decreased inferior glide and lateral distraction of GH joint. -Short subscapularis and lateral rotators, supraspinatus, deltoid. -Weak rotator cuff muscles. -May find positive tests for rotator cuff tears and impingement. -Often associated with scapular downward rotation syndrome. So how does this happen? With elevation of the humerus, there tends to be over-activity of the deltoid muscle and decreased activity of the rotator cuff muscles responsible for inferior glide of the head of the humerus. If you are able to either increase deltoid activity or increase rotator cuff activity, a decrease in pain will be noted. While we should treat every patient based on the impairments they present with, I will list some of the important treatments I have found based on common impairments with this syndrome. Mobilization of the inferior capsule of the GH joint is necessary due to the excessive superior glide and lack of inferior glide. Exercises to restore the scapular fault are important as that provides the base for the shoulder. Since this syndrome is often associated with scapular downward rotation, I like to do standing wall shrugs to improve upper trap function. This must be coupled with decreasing the downward force the arms play on the humerus. It can be done by crossing arms against chest when unsupported or using well-positioned arm rests. Rotator cuff exercises are important as well. Sahrmann recommend using prone ER in 90 deg of abduction to improve infraspinatus and teres minor function. This helps to decrease posterior deltoid activity, unlike shoulder ER in adduction. Supine shoulder IR/ER can be used to regain shoulder mobility but I recommend it be done in 90 deg abduction again to limit deltoid activity. Finally, another exercise Sahrmann recommend is sliding ulnar borders of hands up on wall above head and then exerting a downward force to depress the head of the humerus. Hopefully this helps in identifying patients that you come across with this syndrome! For more information, check out Sahrmann's Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes. -Chris Reference:

Sahrmann SA. Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes. St. Louis, MO: Mosby. 2002. 234-236. Print.

1 Comment

Tension points are areas of the body with little or no movement between the nervous system and it's surrounding structures. Tension points can occur peripherally (at the carpal tunnel or superior tibiofibular joints for example) and centrally within the spinal column. The three main tension points of the spine are C6, T6, and L4. Clinically, it is important to investigate tension points whenever the patient reports radiating symptoms to an extremity. Peripherally, tension points occur where the nervous system branches, at soft tissue or osseous tunnels, areas where the nervous system is relatively fixed, and areas where the nervous system passes closely to surrounding structures. Examples of each of these can be seen below. EXAMPLES OF TENSION POINTS

I've been a fan of Erik Meira for some time now. He has great insight into the world of sports physical therapy as well as the science behind things. In addition, his journey into sports physical therapy is very interesting and uncommon. However, he really did a good job with providing a foundation for those looking to stay more current with the latest research out there. It's so important to stay up to date with the research in your subspecialty area as well as attend conferences and CEU's. Being complacent in the field of physical therapy just won't work. You will get frustrated in the clinic and your patients will not get better. Check out his article and then check out our favorites page with other resources and names to follow. You won't be disappointed. Article Sports Resources Page Favorites page - Brian Regular readers of the Sports Physio blog are well aware that there is definitely at least a dislike towards manual therapy (or what many claim to be manual therapy) with the author of the blog, Adam. He recently put up a post about his frustrations with certain theories of the mechanisms behind physical therapy. The post was well supported with various articles. While the tone of the article is somewhat extreme and definitely opinionated, Adam brings up some very important points, particularly about the lack of any evidence for biomechanical explanations behind manual therapy. In our most recent fellowship class with the Manual Therapy Institute, we covered adverse neural tissue tension and manipulations. The instructors recognize that there is a lack of research to support a specific mechanism behind manual therapy, but do have a hard time factoring in studies as proposed by Adam in his blog post. They offer up both biomechanical and neurophysiological explanations for the techniques. To the casual reader, it would appear Adam's post argues against using manual therapy at all, when in reality, it is just arguing against a particular theory of it - the biomechanical one. Towards the end, he recognizes that most of the current research suggests that manual therapy works via the central nervous system. While this may be true, it is a difficult argument to fully support. According to Shirley Sahrmann, it is impossible to prove a neurophysiological mechanism behind the success of manual therapy. Even though some studies may suggest an existing mechanism behind the theory, we are incapable of actually proving it according to her.

Now the theme of the article would suggest that manual therapy has minimal applications. This may prove discouraging to those who have spent thousands of dollars trying to improve their manual skills. This is the point at which I disagree with the author. I have seen significant improvements in patients in which I use manual therapy. Measure a joint's mobility, perform some IASTM, reassess and find changes in ROM. Assess neural tension, perform a manipulation, reassess and find changes in neural tension. Of course this is not applicable to everyone, but it does affect a lot. There are quite a few studies that have shown improvements in patients after manual therapy has been applied (check out our previous post here). Even though we cannot prove why a technique works, should we stop using it if it is successful? That is the message I fear some will take away from Adam's article. Take IASTM for example. With my IASTM training (IASTM Technique), we learn the theory behind the changes are in activation of mechanoreceptors that allow the nervous system to have altered mobility. There is also some theory about cortical remodeling. Adam links to an article that he uses to defend his belief that IASTM has little effect. However, upon closer look, we do not know enough about the individuals selected in the study (possibly slow-responders) and the study's small sample size of 17 participants do not exactly qualify for normalizing to the population. Many that use IASTM, myself included, have seen immediate changes after the manual treatment alone. Now, of course we must reinforce any changes we acquire through manual therapy with some sore of exercise or education to make the patient more independent and lock in the changes. Manual therapy can be an extremely useful tool to accelerate your treatment plan. Be flexible as research continues to come out about manual therapy that might assist your decision making, but don't throw it away just yet. -Chris From my clinical experiences thus far, I have found that many individuals with low back pain lack proper gluteus maximus strength. (This should not be a surprise to you unless you went to physical therapy school when dinosaurs were still roaming). I often find that the gluteals are weak due to a combination of disuse atrophy and muscle inhibition secondary to pain. In the case of disuse atrophy, the individual does not activate their gluts and therefore preferentially activates other muscles to perform the movement. For example, think about the individual who arches his/her back to pick up a box rather than perform a hip hinge and squat OR consider the individual who rests in lumbar extension, locking out the lumbar facets and resting on the anterior hip ligaments. They avoid the gluteals and activate their lumbar paraspinals and hamstrings to perform movements. With pain inhibition, the gluteals are not receiving proper neuromuscular facilitation because pain is overriding the movement. The muscles are temporarily unable to fire because pain is inhibiting the activation. In either situation, properly assessing hip strength and assessing the cause of weakness is a fundamental part of a low back evaluation. In this post, I want to discuss hamstring dominance is relation to gluteus maximus testing. As I stated in the previous paragraph, poor movement patterns often lead to improper activation of the glut muscles. Since the gluts are not helping perform the movement, a different muscle overcompensates to perform the movement. Clinically, I often find that this other muscle is the hamstrings (or lumbar paraspinals). Individuals that preferentially activate their hamstrings prior to their gluts are called 'hamstring dominant.' This can be problematic because the gluteals are meant to act as a hip stabilizer and extensor. When they do not fire first, the gluteals do not stablize. The hamstrings attempt to act as both a prime mover and stabilizer. The test for hamstring dominance is similar to the Kendall Glut Max testing position. Place the individual in prone with the tested knee bent to 90 degrees. Ask them to lift their leg off the table. In the normal healthy individual, the glut max engages prior to the hamstrings. Proper activation order: 1. TrA engages, 2. gluteus maximus activates, 3. hamstrings fire as the leg is lifted. If the hamstrings fire before the glut max, the individual drives that motion with the hamstrings. In the video below, the individual presents with both hamstring and lumbar paraspinal dominance over gluteal muscle activation. He compensates by arching through his low back and avoids using his glutes. (Video feed has been taken from The Movement Corner on the OPTIM Manual Therapy Felowship Website) Do not be fooled by strong gluts in the low back pain population. After assessing the glut max, retest for hamstring dominance to ensure they are not over-activating the hamstrings. I frequently discuss dominance patterns on The Movement Corner as they are common causes of movement dysfunction. I highly recommend assessing for hamstring dominance in your lumbar patients.

-Jim Heafner PT, DPT, OCS  We have written before about how the pelvic floor is often overlooked by orthopaedic physical therapists, but there is still a lack of awareness of the specialty. People forget that pelvic floor dysfunction can present as low back, groin, hip, LE pain and more. It is more than just "B&B problem." Even though there is a movement in the physical therapy world that is shooting down the importance of core stability training, it is a concept that should not be ignored. When people think of the various components of the core, the two that are often forgotten include the diaphragm and pelvic floor. There is probably more awareness regarding diaphragmatic breathing compared to proper pelvic floor function, but it definitely is still lacking. There are classes about various assessment and treatment techniques for breathing in the orthopaedic world that are accepted due to the ease of application. With the sensitivity around the pelvic floor (no pun intended), we are often hesitant to even subjectively assess the area. Julie Wiebe, PT recently wrote a post about pelvic floor activity with squats. With squats being a higher level exercise, people are often aware of the necessity of core activation, but again let the pelvic floor fall to the wayside. Due to the lack of public education regarding the area, there is a significant amount of inappropriate advice for pelvic floor training. There is an excessive amount of information on the web that advocates for kegels as the solution to any pelvic floor dysfunction. This is often the opposite of what is desired as over-recruitment of the pelvic floor can lock up hip mobility and encourage excessive lumbar mobility. The pelvic floor has an intricate relationship with some of the hip stabilizer muscles and is important for serving as a stable base. Check out Julie's article for further understanding of how the pelvic floor acts throughout the squat and other functional activities. As orthopaedic physical therapists, we need to increase our knowledge of the impact this can have on our clientele. -Chris I have not had many experiences with De Quervain's Tenosynovitis, but I recently performed an evaluation on a woman with a classic case of the pathology. In this post, I perform a mini-review on the syndrome and give a reflection on own evaluation. Note: De Quervain's is a pathoanatomic diagnosis. My PT diagnosis was radiocarpal joint dysfunction with repetitive muscle overuse. Additionally, my patient was truly an -itis, her symptoms began days prior and she had repetitively began working despite having pain. Many patients may present with a longer duration of symptoms and would be classified as an -osis. Review: Tenosynovitis is an inflammation of the synovial sheath that surrounds a tendon. Swelling, decreased mobility, and pain often occur in the presence of tenosynovitis. The two tendon sheaths that become irritated are the Abductor Pollicis Longus (APL) and Extensor Pollicis Brevis (EPB). [To recall these tendon, remember one is a longus and the other is a brevis. Then, think of the word apple (APL). If you can recall APL, remembering the second tendon is easy.] These two tendons are found in the first compartment of the wrist and together perform a movement called radial abduction. Typical patient presentation includes middle-aged women, pregnant, and overuse injuries. Impairments include pain over the first compartment of the wrist, decreased wrist and finger ROM and joint mobility, decreased grip strength, and difficulty grasping objects. Clinical diagnosis can be made by performing Finkelstein's test along with palpation of the involved tendons, A/PROM assessment, joint mobility assessment. The astute clinician should rule out 1st CMC osteoarthritis because the two pathologies will have a similar presentation. Finkelstein's Test My Eval and Treat

The treatment of De Quervain's Tenosynovitis should be based off the patient's individual irritability level and should address primary impairments. In my case example, the patient presented with high pain levels and decreased ROM noted in all planes with the greatest limitation moving into pronation. She had joint mobility restrictions at the 1st CMC joint as well as the radiocarpal joint. I ruled out 1st CMC OA because the patient did not meet the age criteria and palpation of the 1st CMC was unremarkable and joint mobility assessment did not reproduce her symptoms. For her treatment, I performed GI and II mobilizations at the radiocarpal joint for pain relief. Additionally, I prescribed gentle stretching of the APL and EPB in the pain free range as well as pronation AROM within the pain free. Finally, I gave the patient a wrist splint to avoid further over-use of the tendons while returning to work. Additionally, I gave advice on proper ergonomic set-up and workplace posture. In reflection, I should have spent more time working proximal and central. I believe I did a nice job treating some primary impairments, but did I really address the cause of the problem? Probably not! Looking at the spine, shoulder girdle, and inquiring further about workplace set-up would have taken my eval to the next level. In my defense, the patient was a walk-in evaluation. I only had limited time and resources on the day of the evaluation. I will definitely investigate more proximal, central at the follow-up visit. Thanks for reading! Do not forget to check out our premium page for exclusive content! -Jim Attention SPT followers: You can officially sign up now for our premium page content!! You will have your own unique log in for unlimited access for only $4.95/mo or $49.95/yr. That's unlimited access to podcasts and videos from orthopedic and sports residency trained PT's! New content every month. See the link below for more information: http://www.thestudentphysicaltherapist.com/premium-page.html About a month ago, one of the physical therapists at my clinic did an inservice on the exercises she prescribes for the shoulder. She recently graduated from PT school and had done one of her final clinical rotations with Todd Ellenbecker from whom she basis her shoulder rehab. For those of you unfamiliar with Ellenbecker's treatment approach, each and every shoulder patient gets the exact same shoulder exercises. This was confirmed by my co-worker. The idea that a "cookie-cutter" approach is effective can be frustrating to the diligent therapist. Why take all the strength and ROM measurements if you are going to apply the same exercises anyway? It's not that these generic approaches don't work, because they often do! If you think about your past cervical, shoulder, or whatever evaluations, you may recall that there exists a common set of impairments. Likely, the scapula are downwardly rotated, the middle and lower traps are weak, there is a hypomobile posterior capsule, and more. Impairments like these are so common, because of the frequency with which we assume certain postures (like FHP) and perform repetitive motions throughout each day. Because of this, many shoulder pathologies present with similar impairments and, thus, can be successfully treated the same way.

But what if they don't fall into the majority? Sure most people have limited occipitoatlantal flexion due to forward head posture (FHP), but not everyone. Most people respond well to repeated lumbar extension, but not everyone. The problem of always treating based on common impairments, instead of actual impairments, is that eventually you will run into the patient that does not fall into the majority. They will not respond to your treatment and not get better. Sure, most of the patients will improve, but not all. Or maybe they won't get 100% better. It is for this reason that we cannot blindly apply the same exercises to everyone we treat. We actually talked about how Ellenbecker is referred to as the shoulder and elbow expert by the APTA. You don't get to that level without some significant success, and the majority of patients improving (based on this approach) will form a large following, but may limit your expertise. Base your treatments off of impairments. If you stretch a lengthened muscle or mobilize a hypermobile joint, you may actually make a patient worse! Physical therapy does not have to be as difficult as we like to make it. The key is keeping an open eye to find all relevant impairments and treat accordingly. Knowing the common patterns may allow you to speed up the process, but if you ignore the exceptions, you will fail to make progress. -Chris |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed