- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

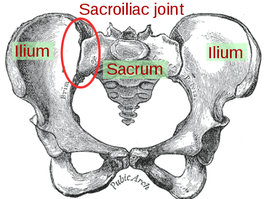

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

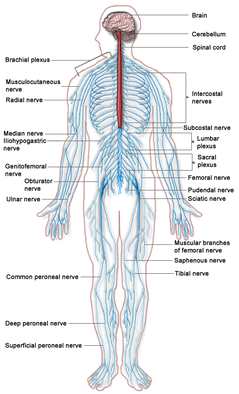

A similar technique often confused with nerve gliding is nerve sliding. Nerve sliding works by elongating the nerve bed at one joint, while simultaneously shortening it at another (Coppieters & Butler, 2008). The reasoning is that the nerve can move without increasing strain. It was found that nerve sliding creates the largest nerve excursions with the least amount of strain. Nerve gliding can potentially create even larger nerve excursions at proximal joints but it creates significant strain. Due to the chance for symptom provocation, nerve gliding should only be considered in non-acute and non-surgical conditions. It is here that nerve sliding is the preferred intervention. A recent study found that the sequencing of nerve tensioning/gliding at each joint was irrelevant when looking at net strain on the nerve (Boyd et al, 2013). However, it was also shown that variation in sequencing of joint movements altered where the nerve strain occurred first. This has potential clinical implications as we may be able to target specific locations if we know where the restrictions lie. The real-world applicability is unknown at this point as there have not been any studies performed in this area. When comparing education to education + neural tissue management (both nerve sliding/gliding were used with cervical manual therapy), it was found that the intervention group had superior results compared to the control with no significant increased risk of exacerbations (Nee et al, 2012). Not only is it important to note the benefit of these nerve gliding/sliding exercises, but it brings up the point that we should also be looking at the spine. Other than some form of direct trauma, another source of nerve irritation can come from poor spinal mechanics that lead to neural irritation. Treating just the nerve may mean treating just the symptoms in some cases. It is essential to look at the spinal and restore normal mechanics if any abnormalities are found, especially because a manipulation may immediately show symptom relief as well. There are two additional treatment techniques we wanted to mention. A case study we looked at utilized Active-Release Therapy (ART) for saphenous nerve entrapment (Settergren, 2012). In general, ART involves a technique where the clinician applies a force to the restricted area while the patient actively moves to "release" the adhesion. The technique often causes significant pain during the maneuver but is followed by increased mobility and decreased pain. This method may not be as useful to most clinicians as it involves extensive training to correctly perform and the research is limited in the area. Another technique that we often perform and have had success with is Instrument-Assisted Soft Tissue Mobilization (IASTM). While we have personally seen immediate effects on pain and neural symptoms with this, again the research is limited in the area. References:

Boyd BS, Topp KS, & Coppieters MW. (2013). Impact of Movement Sequencing on Sciatic and Tibial Nerve Strain and Excursion During the Straight Leg Raise Test in Embalmed Cadavers. JOSPT 2013 43(6):398-403. Coppieters MW & Butler D. (2008). Do "sliders" slide and "tensioners" tension? An Analysis of Neurodynamic Techniques and Considerations Regarding Their Application. Manual Therapy 2008 13(3): 213-221. Web. 26 October 2013. Nee RJ, Vicenzino B, Jull GA, Cleland JA, and Coppieters MW. (2012). Neural Tissue Management Provides Immediate Clinically Relevant Benefits Without Harmful Effects For Patients With Nerve-Related Neck and Arm Pain: A Randomised Trial. Journal of Physiotherapy 58 2012. Web. 26 October 2013. Settergren R. (2012). Conservative Management of a Saphenous Nerve Entrapment in a Female Ulra-Marathon Runner. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2013 Jul;17(3):297-301. Web. 26 October 2013.

6 Comments

Subacromial Impingement Syndrome (SAIS) is reported to be the most frequent cause of shoulder pain in an OP physical therapy clinic. Despite the high prevalence, physical therapists still struggle to appropriately diagnose the syndrome. The gold standard for diagnosing SAIS in arthroscopic surgery. Since we do not have access to this tool everyday, we must reply on our patient examination skills. A study by Michener et al, Reliability and Diagnostic Accuracy of 5 Physical Examination Tests and Combination of Tests for Subacromial Impingement, assessed 5 special tests commonly used to help rule-in SAIS. The 5 tests were Neers, Hawkins-Kennedy, Painful Arc, Empty Can (Jobe), and External Rotation Resistance Test. Specifically this article wanted to assess the interrator reliability of the tests, diagnostic accuracy of each test, and finally if clustering the tests would confirm or rule-out SAIS. The results of the study were surprising. Moderate to Substantial strength of agreement between raters was found for the empty can test, the painful arc sign, and external rotation resistance test. Surprisingly Hawkins Kennedy had the lowest kappa value at .39. We found this surprising because Hawkins-Kennedy is graded as painful or not painful. There seems to be little room for subjectivity, yet it received the lowest reliability among raters of all the tests. The difference likely lies in how the test is performed and thus perceived. It is easy to forget to not horizontally adduct the shoulder sufficiently or to ignore the patient's compensation of elevating the tested shoulder during IR as a means of avoiding/minimizing the pain provocation. Something we must always be wary of in studies of manual techniques is accepting the fact that all examiners perform/analyze movements the same. When looking at the diagnostic accuracy of each test individually, the External rotation resistance test had the highest positive likelihood ratio (LR) of 4.39, empty can had the second highest with 3.9, and the painful arc sign came in third at positive LR 2.25. Finally, the article found that when clustering the tests a "combination of any 3 positive tests out of the 5 have the best ability to confirm SAIS, with small to moderate shifts in the pretest to posttest probability." While this article provides interesting and useful clinical information, the results are different from other studies in the literature. A separate article on SAIS by Park et al found that the clustering Hawkins-Kennedy, Infraspinatus Muscle Test, and the Painful Arc Sign yielded a high +LR (10.56) for ruling-in SAIS. So what cluster should you use? Personally, we would use both. The etiology of SAIS is multifactorial. Several structures have the potential to be pain generators and the presentation of SAIS will vary based on posture, scapulohumeral rhythm, accessory joint mechanics, and more. The Michener article was quick to point out the importance of a thorough subjective history to help aide in the diagnostic process. Reference: Michener LA, Walsworth MK, Doukas WC, Murphy KP. Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of 5 physical examination

|

| When most people think of McKenzie method, they think of extension based exercises and herniated disks. That is but the tip of the iceberg. A true understanding of the system that McKenzie offers can provide tools to help clinicians both diagnose and treat various conditions in the spine and extremities. In a recent post, Dr. E from The Manual Therapist reviews exactly what directional preference is and why we sometimes need to test/treat with sustained or repeated motions. Directional preference refers to motion in any body part that needs to be sustained or repeated to end range in order to improve ROM, pain, DTRs, strength, and/or function. Dr. E provides common treatment methods throughout the spine in this post. He doesn't discuss loading in the extremity as much here, but that isn't the point. The purpose of this article is to raise the importance of determining if/where the directional preference lies, and how to treat it. Definitely worth checking out. |

Insider Access pages

We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!

Archives

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

October 2016

September 2016

August 2016

July 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

March 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

November 2015

October 2015

September 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

May 2015

April 2015

March 2015

February 2015

January 2015

December 2014

November 2014

October 2014

September 2014

August 2014

July 2014

June 2014

May 2014

April 2014

March 2014

February 2014

January 2014

December 2013

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

August 2013

July 2013

June 2013

May 2013

April 2013

March 2013

February 2013

January 2013

December 2012

November 2012

October 2012

September 2012

August 2012

Categories

All

Chest

Core Muscle

Elbow

Foot

Foot And Ankle

Hip

Knee

Manual Therapy

Modalities

Motivation

Neck

Neural Tension

Other

Research

Research Article

Shoulder

Sij

Spine

Sports

Therapeutic Exercise

RSS Feed

RSS Feed