- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

|

Overview: The SLUMP test is a highly sensitive test that can elicit positive neural tension in even asymptomatic individuals. The test can be used in conjunction with other neural tension testing (straight leg raise) and is often a great concordant (asterisk) sign to demonstrate within treatment progress. Due to the complexity of this test, consistency is key. To ensure you are performing the SLUMP correctly, you must be systematic. Perform the same order of events with every patient, every time. Proper Start Position: 1) The patient sits upright with their popliteal creases against the back of the plinth. 2) The therapist presses the knees together and releases them to maintain a neutral position of the lower extremities 3) The patient folds their arms behind their low back *These 3 steps are to maximize consistency Performing the Test: 1) Have the patient slowly slouch from their thorax spine (this will also create lumbar flexion) 2) SLOWLY flex the head toward the sternum 3) SLOWLY begin extending the knee* 4) SLOWLY dorsiflex the ankle* 5) Extend the cervical spine (move a distant component) *In steps 2, 3, and 4, I emphasize SLOWLY because the test is intended to pick up adverse neural tension. Many individuals will push past the onset of neural tension and confound the results of the examination. Remember, neural tension is only positive if their is a side to side difference, reproduces their primary complaint of pain, and if symptoms change by moving a distant component. Turn the SLUMP Test into a Treatment: Fortunately, setup and treatment for positive neural tension findings can be very similar. Check out our HEP program page on Slump Sciatic Nerve Glides to improve your intervention selection. Additionally, for more information on neurodynamic testing and treatment check out our guest post from Darrin Staloch. -Jim Heafner PT, DPT, OCS Learn more about the Lumbar Exam!TSPT Lumbar Spine course has over 5 hours of lecture dedicated to lumbar examination, treatment, biomechanics, and more! The course outlines multiple treatment options include Sahrmann, repeated motions, and manipulative therapy. Click below to learn more!

0 Comments

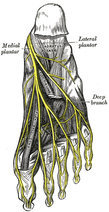

Plantar Fasciosis can be a very difficult condition to treat because of the intricate anatomy of the foot and ankle complex. To complicate issues, we now know that many lower quarter problems root from lumbopelvic and hip dysfunction as well. In previous posts, TSPT has done a literature review of the condition as well as talked about new treatment methods regarding plantar fasciosis. In these posts, one aspect of management we did not discuss in depth is assessing for neuropathic pain. From my clinical experiences and the experiences of my colleagues at the Harris Health System, many patients with plantar fasciosis have positive neural provocation tests for the distal branches of the tibial nerve. Anatomy Review After the tibial nerve passes around the medial malleolus, it splits into three distal branches: the medial plantar nerve, lateral plantar nerve, and medial calcaneal branch. Specifically, the lateral plantar nerve innervates the fifth and lateral 1/2 of the fourth toes and provides motor input to many of the intrinsic foot muscles. The nerve passes laterally across the foot and splits between the flexor digitorum brevis and quadratus plantae. Assessment To assess for tibial nerve adverse neural tension, have the patient lie supine. Passively extend the toes, dorsiflex and evert the ankle. This combined movement place a stress across the tibial nerve and its distal branches. Ask the patient if this position changes their primary symptoms (better, worse, or the same). Next, passively perform a straight leg raise maintaining the foot and ankle components. If this position recreates their primary symptoms, they have positive neural tension in the tibial nerve* (remember to test bilaterally as well). To further assess the tibial nerve, adduct and internally rotate the lower extremity. If the test is positive, appropriate treatment options include nerve sliders, tensioners, and manual therapy. *When performing a straight leg raise, you are changing the hip component. No musculoskeletal structure courses from the hip to the ankle, so if symptoms change it must be the nervous system that is being assessed. Conclusion -Lateral plantar nerve pain can be a contributing factor to plantar fasciosis pain. -By performing the proper assessment (discussed above), you can identify if neural tension is part of your patient's symptoms. -Do not underestimate the impact of the peripheral nervous system in musculoskeletal dysfunction. Lower Extremity Peripheral Nerve Testing [Video taken from TSPT Insider Access Library- subscribe to learn other advanced assessments!] Author: Jim Heafner PT, DPT, OCS is one of the founders of The Student Physical Therapist. He is owner of Heafner Health Physical Therapy in Boulder, Colorado. Are You on the Inside?Looking for advanced sports and orthopedic content? Take a look at our BRAND NEW Insider Access pages! New video and lecture content added monthly.

The problem In the general public there seems to be a lack of awareness regarding neural dynamics. Everyone knows muscles and joints require movement, but people do not think about the nervous system as a mobile unit. As a profession, physical therapy is gaining more knowledge regarding neural dynamics and incorporating these principles into our treatment sessions and home exercise programs. Unfortunately, we are not doing an adequate job explaining to patients WHY we are performing these exercises. What is important to know about the nervous system? The body is one unit of interconnected nerves stemming from the brain. Healthy nerves require regular movement to stay lubricated and mobile. Unhealthy nerves are less pliable and can get trapped or compressed creating nerve tension. Decreased pliability increases the risk of injury because of the high amount of oxygen required by the nervous system. The nervous system receives 20% of the body’s blood supply, yet comprises only 2% of the body’s weight. It relies on adequate oxygen to function, and whenever that supply is disrupted, problems (manifested as tension) occur. The above paragraph is brief summary of a 2009 3 part series, by Todd Hargrove on Nerve Mechanics. These easy to read blog posts will give you simple tips to explain nerve pain to your patients. -Jim  General Overview Time and time again, the Occupational Therapists in my clinic get referrals for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS). In some of these cases, the patients also have cervical pain, shoulder pain, proximal forearm weakness, and/or palmar paresthesias. While these individuals may have compression within the carpal tunnel, many of them are suffering from nerve entrapment proximal to the carpal tunnel. Many develop adverse neural tension caused by postural dysfunctions, muscle imbalances, and systemic comorbidities which cause a breakdown of the nervous system. Am I saying CTS is over-diagnosed? That is exactly what I am saying. It has become a blanket term for pain in the wrist and hand just as lateral epicondylagia has at the elbow. Many times, the cause of someone's symptoms is not consistent with the referring diagnosis. In this mini-review, I will break down a few areas of entrapment of the median nerve and how to assess for adverse neural tension within the median nerve. Median Nerve Pathway The median nerve is formed from contributions of the spinal nerve roots C5-T1. After originating from the brachial plexus in the axilla, the medial nerve travels down the arm to the cubital fossa. Next, the nerve travels through the two heads of the pronator teres and between the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus muscles. At this point the median nerve splits into the anterior interosseous nerve (AIN) and palmar cutaneous nerve. Finally, the nerve travels through the carpal tunnel space. (Be aware there are many alternative anatomy presentations; this is simply one of the most common ones). As you can see there are many points of entrapment for the median nerve: the cervical spine, interscalene musculature, between the heads of the pronator teres, and within the carpal tunnel (among other less common ones). The patient's subjective reports and your clinical examination will point you to the correct structure and location of dysfunction. When suspecting neural tension, a clinical examination measure you should utilize is the Median Nerve ULTT. Assessing for Adverse Neural Tension & Different Sites of Entrapment We have discussed adverse neural tension several times before on The Student Physical Therapist (How to assess neural tension, Differential Dx in neural tension). At the Harris Health Orthopedic Residency, I use 3 distinguishing criteria for positive adverse neural tension testing. The symptom(s) must reproduce the patient's primary complaint, it must change by moving a component at a joint proximal or distal to the complaint, and it must be different side to side. To see the full test for adverse neural tension of the median nerve, click HERE. This test will not tell you the exact location of symptoms, but it will give you an understanding of the sensitivity of the nerve. In addition to performing neural tensioning tests, it is important to perform a thorough assessment of other potential areas of entrapment. For example, if you find muscle wasting in the FPL, pronator quadratus, and/or radial half of the FDP, the involved nerve is likely the AIN being compressed in the proximal forearm. Additionally, if the patient has comorbidities that affect the nervous system, such as a history of uncontrolled DM, this can significantly alter your patient presentation. Several clinicians I work with relate this to a form of double crush injury: the nerve is being mechanically entrapped and is also receiving compression from other intrinsic sources. Continue to use your differential diagnosis skills to determine the source of one's symptoms. It may save your patient from an unnecessary surgery. -Jim |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed