- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

|

In the video below, Kelly Starrett discusses how sitting throughout the day places the hip joint in a poor position for normal daily movements. In the video he discusses how prolonged sitting places the psoas muscle in a short, contracted position. As an individual attempts to stand from this position, he/she hyper-extends the lumbar spine. Biomechanically, a tight psoas and shortened lumbar paraspinals draw the pelvis into an anterior pelvic tilt and the lumbar vertebrae into extension. Be aware: the chest may appear upright- giving the impression of natural movement,- but a closer look at the L-spine reveals movement beyond the neutral range. The problem with sitting exists beyond the chair as well. Normal standing posture requires little muscular action to maintain an upright position. In the presence of a hip flexor contracture due to prolonged sitting, forces are placed anteriorly across the hip requiring the hip extensors to counteract the force. Increased muscular action and metabolic cost creates the desire to sit, perpetuating the circumstance which initiated the hip flexion contracture (Neumann 2010).

The Student Physical Therapist Advice: Engage the Transversus abdominus (TrA) prior to moving from sitting to standing. The TrA provides a posterior pelvic tilt to counteract the force of the psoas muscle. Additionally a posterior tilt does not allow the lumbar paraspinals to contract as readily. With proper cueing, the gluteus maximus can then be engaged and stress will be taken off the low back. Enjoy the video- Jim References: Neumann, Donald. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System: Foundations for Rehabilitation. 2nd edition. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier, 2010. 341-342. Print.

2 Comments

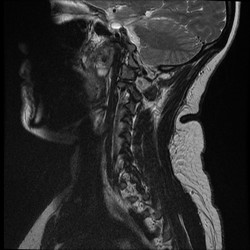

In school, many students are taught about the clinical significance of imaging, but how many end up utilizing it clinically? It seems like I rarely go a day when I don't hear a patient or clinician mention how bad the patients' MRI findings are and how that is the reason for the patient's symptoms. "So and so blew out a disc lifting a heavy box," "I have 3 slipped discs in my neck," or "the MRI revealed impingement at C4." The list goes on and on; however, my personal favorite is "my knees are bone on bone!" Sure the MRI can pick these things up, but do they matter? While I support the use of imaging to help rule out various non-musculoskeletal pathologies and life-threatening symptoms, there is quite a bit of evidence that says we should not rely on imaging for things like determining the significance of herniate discs, stenosis, bone spurs, and more (Boden et al, 1990 & Jensen et al, 1994). What these studies reveal is that quite a few people without any symptoms or complaints have the same MRI findings as those with pain. What does this mean? While it is theoretically possible that findings like stenosis, bone spurs, and discs can create various symptoms, just because we see something on an MRI does not mean that it is the source of our patient's symptoms. This is why I get frustrated when I hear patients (or PT's) start to list off their findings or when patients and health care practitioners are pushing for surgery. As clinicians, we should regularly educate our patients on just how insignificant some imaging results can be in regard to orthopaedic complaints. What we have discussed thus far does not even touch upon our understanding of modern pain science. Having recently completed Butler and Moseley's Explain Pain, my understanding of what "pain" actually means and how it develops has changed drastically. We don't actually have pain receptors. We have an intricate system of "danger" (noci-) receptors. This system is influenced by different cultural upbringings, our surroundings, and much more. It can even adapt to affect and be affect by other parts of the nervous system! What we feels as pain often occurs for a reason, to warn us. However, the nervous system can become hypersensitive and lead to various types of chronic pain. Think about diagnoses such as Chronic Regional Pain Syndrome. These patients actually visualize the affected body part as being enlarged! How is it that someone with horrendous pain from a "blown disc" can immediately get near 100% within a couple days with something like repeated motions? We aren't pushing the disc back into place; we are affecting the nervous system! This ties right back in with abnormal imaging findings. We cannot let the results of an MRI impact our clinical decisions and treatments based on this. I am not advocating against the use of MRI's (or other types) in general, but I believe we do a disservice to our patients by biasing their mind with MRI results before even giving therapy a shot. This thought process alone can affect how the patient perceives their disability and affects the function of the nervous system. With the right treatment technique (repeated motions, manual therapy, chronic pain education), most patients should see improvement. -Chris Reference:

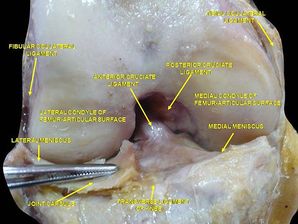

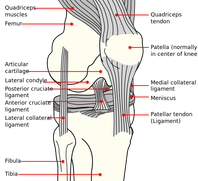

Boden SD1, Davis DO, Dina TS, Patronas NJ, Wiesel SW. (1990). Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990 Mar;72(3):403-8. Web. 24 Aug 2014. Butler D & Moseley L. (2013). Explain Pain: 2nd Edition. NOI Group. 2013 Sept. Print. Jensen MC1, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian D, Ross JS. (1994). Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994 Jul 14;331(2):69-73. Web. 24 Aug 2014.  A few weeks back I posted an article discussing a recent knee injury I sustained. In that post I outlined several important pieces of information often under-looked when rehab'ing a knee. As of last week, my rehabilitation was going great: I had returned to running for >1 hour, performing weighted squats, and only having pain at end-range flexion. This all changed 1 week ago when I returned to wake boarding for the first time. While performing a trick, I landed wrong and re-injured my knee. I experienced similar symptoms to my first injury: a pop, immediate pain, and swelling. Under the supervision of a nurse practitioner, we agreed it would be best for me to get an MRI to rule out ligament or osteochondral lesions (Phisikil 2006). The MRI impression (verbally per NP): 1) Meniscofemoral ligament rupture 2) MCL and ACL sprain (fortunately not torn) 3) Intact meniscus 4) No chondral lesions Based off the impression, it appeared I dislocated my patella during the injury (unknown to me). Once again I needed to start conservative management. In this post I am going to do a brief knee anatomy review of the ACL and MCL as well as discuss conservative management of these injuries.

Conservative management of an MCL injury: Non-operative management has been proposed as the mainstay treatment for MCL injuries (Phisikil 2006). With an isolated MCL injury, treatment consisting of protected ROM and progressive strengthening has been shown to produce excellent results. During the inflammatory phase, use the RICE principle to minimize pain and swelling. Use crutches until the individual can walk without a limp. As the patient progresses, both the stair climber and the bicycle ergometer are easy methods of maximizing ROM and minimizing stiffness. Once range of motion is restored, lower extremity progressive resistive exercises should be initiated. I have been following the above protocol closely with good success. One consideration I need to take into account is the concomitant ACL sprain. Although the research is lacking on multi-ligament conservative management, I am guiding my ACL rehab by both pain and the knowledge of ACL stress/strain. Since my ACL is healing, I want to avoid exercises that place excessive strain across the ligament. At the same time, the ligament does need some stress to allow for normal collagen realignment. Thus far I have mainly been performing closed chain activities and riding the bicycle. Fortunately I do not have any meniscal or articular cartilage damage which allows me to progress loading at a faster rate. I hope this mini-anatomy and conservative management review was helpful. -Jim References:

Phisitkul P., James S.L., Wolf B.R., Amendola A. (2006) MCL injuries of the knee: current concepts review. Iowa Orthopaedic Journal 26, 77-90 As you know, we have reported in the past about using the edge mobility band for things like increasing hip IR, tibial IR, or ankle DF with MWM techniques. It's success is primarily based upon the theory that it engages mechanoreceptors and alters fascial mobility via changes in sympathetic nervous system. Additionally, it enhances the grasp by the clinician for MWM. Recently, I had a couple of instances where I tried using the mobility band that I had not previously trialed. In one case, I was treating a patient s/p ACL reconstruction just a couple weeks out. She was presenting with significantly limited flexion ROM secondary to medial thigh and proximal tibia pain. These aren't your traditional pain locations from surgery and led me to believe it was more neural-based. The next session, I applied a mobility band over the thigh and over the proximal tibia. The patient immediately reported she no longer had pain. This allowed the patient to tolerate PROM and her exercises much better. The second case was a patient who had reports of neural symptoms and a sensation of "weakness" in his UE. He had been responding, albeit slowly, to IASTM with his symptoms decreasing. On his last treatment session, a mobility band was applied over his affected UE near the elbow for his exercises. The patient reported he was able to complete all exercises with no abnormal sensations in his UE. Being able to change our patient's symptoms with the bands can be crucial to maximizing their time in treatment. Our patients can tolerate manual therapy and exercise better, thus possibly allowing for larger gains. Check out the pictures below to see where I applied the bands. Depending on your patient's presentation, a different application may be required.

-Chris  A few weeks ago, I read an article about the need for developing a system for assessing hip rotation ROM in weight-bearing compared to our standard NWB positions. While it is great that researchers are becoming aware of the differences between anatomical ROM and functional ROM, the study has a somewhat limited focus on female golfers. In reality, the importance of these differences apply to all patients, not just athletes. As we have stated in previous posts, we strongly encourage the type of systematic assessment for mobility that is included in the Selective Functional Movement Assessment (SFMA). The beauty of the evaluation method is that it takes the patient through various levels of required motor control for each combined or single movement. This is an essential concept as it can get to the root of the problem. With our standing tests of combined patterns, mobility, motor control/stability, and postural control are all required. If a dysfunctional movement pattern is found, the patient then is taken into a NWB (or less WB) position, where the test may be performed again. You may be surprised to find your patient's pattern is now fully functional! Should the pattern still be dysfunctional, each pattern can be broken down and tested actively versus passively to determine if mobility or stability/motor control is the primary concern. Whether you use the SFMA system or another method, assessing movement with various levels of stability is something we should consider with all our patients. Without adequate examination, we may be mistreating the impairments of our patients. Why stretch a hamstring in someone that can't touch their toes if they have 80 degrees of active SLR? By breaking down each level of stability, we can better determine the true source of the patient's limitations. -Chris  Introduction At the Harris Health System, many clinicians practice Shirley Sahrmann's movement impairment syndromes. Utilizing Sahrmann's principles helps guide the clinician toward movement dysfunctions often caused by prolonged postures and repetitive micro-trauma. Since Sahrmann focuses on movement impairments, her syndromes are named using pathokinesiology and kinesiopathology. For the purposes of learning, in this post I will include pathoanatomical diagnoses that relate to lumbar extension rotation syndrome (ERS). Evaluation When performing a lumbar evaluation, assessing for lumbar extension rotation should be a priority. General presentation includes: >55 years old, chronic low back pain, and may be involved in a rotational sport (golf, tennis, etc). On physical examination, you will observe an exaggerated lumbar lordosis, paraspinal muscle asymmetry, excessive pelvic rotation during gait, and hinging during cardinal plane extension testing. They will often complain of unilateral lumbar pain that increases with extension and is relieved with non-weight bearing lumbar flexion.

Clinical Tests In addition to my findings during my functional assessment and observation (stated above), there are many clinical tests used to diagnose lumbar ERS. A few tests I commonly perform are 1) supine bent knee fallout, 2) prone knee bend, 3) quadruped hip extension, and 4) single limb stance. With each of these tests, the examiner should be looking for lumbopelvic compensation (extension and rotation) on the involved side. This compensation generally occurs due to poor timing, coordination, and strength of the core and hip musculature.

Try these tests on a few of your patients and watch how their low back compensates! Let me know if you have any questions or want more information regarding other tests you can perform.

-Jim |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed