- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

|

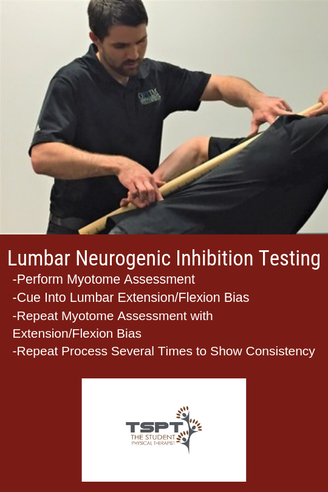

Last year I wrote an article about neurogenic inhibition testing. Neurogenic Inhibition is the concept that the muscle's ability to produce resistance and contractile force is limited by the neural input, not the true muscle strength. It is indicated when either a muscle became weaker with repetitive resistance testing or if the strength improved when resistance was gradually increased. In the past, I addressed these conditions with focusing on improving mobility along the path of the nerve and with strengthening the affected muscles.  About Neurogenic Inhibition One of my favorite aspects of my fellowship mentoring hours is that my mentor has a different treatment style and background compared to me. My training is more in line with Optim Manual Therapy's Fellowship, while my mentor went through NAIOMT's Fellowship. His coursework put a greater emphasis on testing and treating Neurogenic Inhibition. To evaluate a patient for Neurogenic Inhibition, test a patient's muscle strength with a relaxed lumbar spine, then repeat the same testing with a PPT and APT. If the strength completely normalizes with a bias of the lumbar spine, it would be positive for Neurogenic Inhibition. NAIOMT's theory is that the affected segment is "unstable" in a certain direction (decreasing the signal from the nervous system) and the lumbar spine bias provides stability that improves the neural input. An example would be supine ankle DF strength testing that was 4/5, but with the extension bias to the lumbar spine immediately becomes 5/5. The opposite may apply as well. In that same example, the 4/5 ankle DF strength may become 3+/5 with a lumbar flexion bias. It is worth testing and re-testing. Free Preview of Insider Access!I'm not saying that I agree with the theory, or that there is even any research to support this assessment method; however, I have noted regularly that strength changes can occur with changes in spinal positioning. The method that my mentor treats these cases is that he works on increasing strength and activation of the spine in the deficient region and then supplementing that activity with exercises that work the affected myotomal levels. For example, I evaluated a patient this past week that had 4-/5 strength of his R glutes, ankle DF and ankle eversion, all of which became 5/5 with lumbar bias into extension (complaints of drop foot for 4 years after cervical spine surgery). Some exercises we went over included ones that bias the lumbar spine into extension (APT) and work the glutes, toe extensors, and ankle eversion. Proposed Theories It may be that the patients improve because of increased "stability" in the dysfunctional direction, it may instead be due to improving mobility in the dysfunctional direction, or it may be something else altogether. However, because there is so little research in the area, we don't even know how effective the method is in the long-term; however, it is worth exploring due to the immediate changes that can occur. I like to implement Neurogenic Inhibition Testing to help direct my treatment direction. I have found that this same assessment method tells me which direction a patient may respond to repeated motions. Using the same previous example, if the strength improves with lumbar extension bias, I would have the patient perform repeated lumbar extensions (or a variation of it) and recheck the strength. In most cases, the strength is improved afterwards without doing the same biasing. In fact, the patient I described came back from the evaluation with a HEP of press-ups with a R bias and his ankle DF/eversion and hip abduction strength were all 4+/5 without any lumbar spine bias. It is far too early to tell if any long-term or practical changes will occur however the testing may still play a role. It can be useful when a patient is so acute that they may not be ready for a full repeated motions assessment. In general, my treatment method is going to stay the same as discussed in the previous article: improve mobility of the nervous system along the entire path, wherever restricted, and strengthen the affected muscles. I may get there differently with this alternative testing method and I may incorporate some of the treatment theories as well. -Dr. Chris Fox, PT, DPT, OCS See More from The Student Physical Therapist

1 Comment

"I was confronted with the ethical dilemma, do I tell him his ACL is likely torn or not."I was recently working with a 16 year old, active young man who injured his knee while playing rugby 6 days prior. During the initial evaluation, he reported quickly decelerating on the field while pivoting his body. He only had minimal pain, and his swelling was quickly improving with each day following his injury. Additionally, he had a rugby tournament overseas in 2 weeks that he needed to be in good athletic condition to play. As I continued to the examination, I performed the Lachman's Test, which was positive, as well as a positive Anterior Drawer Test. Despite the positive finding, he denied any buckling, locking, or catching. His clinical examination was negative for meniscal pathology and other ligament insufficiency. At this point, I was confronted with the ethical dilemma: Do I tell him his ACL is likely torn or not? On one hand he was making good progress with rest and gradual return to activity. Would the diagnosis of a torn ACL create thought viruses that would hinder his progress with conservative treatment? On the other hand, if he had a torn ACL, does he potentially have other associated injuries? Segund fractures are present in 75-100% of ACL tears. Lateral meniscus tears occur in 54% of acute ACL injuries.

"The MRI identified a fully torn anterior cruciate ligament and bucket handle tear of his medial meniscus."The following week, he travelled with his rugby team and played in several matches. Upon his surgeon's recommendation, he would have surgery after the tournament to reconstruct his ACL and repair the meniscal tear. In this case, should surgery have been avoided? Was his ACL surgery really necessary? Is ACL Surgery Really Necessary? For many many, a torn ACL was synonymous with surgery. However recently, the optimal management of ACL injuries has been placed under question. Recent research, 'A Randomized Trial of Treatment for Acute Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears,' identified that ACL reconstructive surgery was NOT superior to conservative management of ACL tears in young active adults. A second study by Meuffels et al, found similar outcomes between surgical and non-surgical groups at 10-year follow. The authors concluded, "we found no statistical difference between the patients treated conservatively or operatively with respect to osteoarthritis or meniscal lesions of the knee, as well as activity level, objective and subjective functional outcome." If the outcomes are similar, why are surgeons still being performed at an alarming rate? As with most questions in physical therapy, the answer depends on a variety of factors. Clinically, I try to identify if the patient is a 'coper' or a 'non-coper.' Copers are individuals who can function at their desired level despite having a torn ACL. Non-copers are individuals who are unable to function at their prior level following an ACL injury. Copers will demonstrate good quadriceps strength, no buckling or giving way in their knee, and strong, pain free hop tests following conservative rehabilitation. Non-copers will continue to have giving way of their knee, pain that limits function, and subjective reports of decreased quality of life. Regardless, whether someone is a coper or non-coper, it is important to educate them on the pro's and con's of both surgery and rehab. Final ThoughtsAs research continues to develop, we know at least one thing, the ACL is not vital for stability of the knee. Complications and risks will exist on either side of the equation. Patients can have success with both rehab and surgery. The job of a good physical therapist is to present the best available evidence and guide the patient in deciding which treatment option is MOST appropriate for them. -Jim Heafner PT, DPT, OCS Check out TSPTs NEW Knee Course!Save $10.00 using the promo code: ACLrehab Our Insider Access Library is Growing!

References:

1. Frobell RB, Roos EM, Roos HP, Ranstam J, Lohmander LS. A randomized trial of treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tears. N Engl J Med2010;363:331-42. 2. Meuffels DE, Favejee MM, Vissers MM, Heijboer MP, Reijman M, Verhaar JA. Ten year follow-up study comparing conservative versus operative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament ruptures: a matched-pair analysis of high level athletes. Br J Sports Med2009;43:347-51. Did the title of this post catch your eye? Articles with similar titles have caught my eye for years in my quest to understand proper sports rehabilitation and return to sport. Yet, despite completing a sports physical therapy residency with USC in 2014 and becoming a board certified sports physical therapist, I still find myself searching for more answers every day. I end up with more questions most of the time (which I think means I’m on the right track?).

Regardless of my current quest to continue to improve my knowledge and ultimately application of knowledge in return to sport, there are a few things I have learned that are worth sharing. Return to sport is a big buzz word and I feel confident saying that not one person has all the answers. I’ve been lucky to be in a residency class that boasts two NFL physical therapists (Rams & Eagles) and every conversation I’ve had with them (in the past and recently) demonstrates to me that they too are constantly searching for ways to improve these processes. Which is pretty crazy because they have great track records. My interest in ACL return to sport stems from my love for basketball and my years of special interest in treating the basketball athlete. Unfortunately, too many basketball players suffer from ACL injuries. This sparked my interest in understanding why this happens, how we can better prepare these athletes (prevention), and what we can do to successfully return them to sport at the highest level. I say return to sport at the highest level because too often I see players return to practice level but not full game level. Currently, literature has focused on more objective criteria and milestones based progressions. However, as we know, it does take the literature time to catch up to what we see anecdotally. Functional tests are good but do not take into consideration reactive measures. I find myself using these tests but often adding in different movement testing with reactive components to try to mimic sports. After all, almost all movements in sports are unplanned. Training our athletes during their rehab or injury prevention in reactive environments can be very useful. How can we start to train “reactive” components? I find it best not to overthink this and I often use auditory commands or visual commands. For example, when training a basketball player with shuffling in a defensive stance, I will say “Right!” or “Backwards!” or “Left!” continuously for a specified time to signal to the player to shuffle in that particular direction. Using your hands to point in specific directions is another way to do it by challenging a different sensory input. Lastly, using props such as a foam roller, tennis ball, basketball, etc to throw or drop it in a particular direction can be very effective in training reactive first steps. It’s important to note that I often like to record these drills to look at movement both in the moment and afterwards to see what I missed with their preferred movement strategies. ACL return to sport needs to be a multifactorial approach. As this literature article suggests, there are many ways to start preparing our athletes for their eventual return to sport. Understanding the particular athletes sport is something that is also absolutely crucial. Adding psychosocial components, fatigue testing, reactive testing, and sport specific movement based testing is just as important. If you have ACL athletes and do not understand the biomechanics of their sport, take a look through the literature and check out our resources here and here. Most importantly, continue to ask questions to yourself with each athlete you have to find continued ways to improve their outcomes. Dr. Brian Schwabe, PT, DPT, SCS, COMT, CSCS Board Certified Sports Physical Therapist What if there was ONE tool that could help you learn orthopedic evaluations as a student physical therapist (SPT)?What if this same tool reduced errors? And was easy to use, low-tech, and cost $0? Would you use it? What if I told you that tool was a checklist… When you are first learning how to perform orthopedic evaluations as an SPT, the demands on your attention can be overwhelming. Within your evaluation time frame- say you have 20-30 minutes, you must: take a subjective history, perform comprehensive testing (range of motion, strength, joint play, palpation, and special tests), as well as move the patient efficiently through multiple body positions (supine, prone, standing, sitting, etc.), and finally you must distill all of this information into a differential diagnosis. Whew! It is a lot to think about when you first start off! Any tips and tricks to improve efficiency, accuracy, and consistency of your physical therapy (PT) evaluation are truly valuable.  One tool that I have come to rely upon in learning how to perform a consistent and effective evaluation, in a timely manner is The Checklist. As I’ve written about before (Can A Checklist Make You A Better PT?), checklists have been used in various medical settings with positive outcomes (improving patient outcomes, reducing medical errors, and guiding treatment decisions). The checklist does not only function to reduce errors, but I believe it can be an effective learning tool for guiding appropriate practice when learning how to perform PT orthopedic evaluations. If you want to get good at the evaluation process, it is not enough to just practice evaluations. You must take a hard look at HOW you practice evaluations. There has been a lot written about this concept in scientific journals as well as the popular literature on expertise and skill learning. (1,2,5) In order to improve a skill to the level of “mastery” or “expertise”, you must practice that skill in very specific ways. The way you practice must include focused attention as well as a means for receiving reasonably timely feedback. As students, some of this feedback can come from our professors, some can come from peers, but much of our feedback is self-delivered feedback. Setting up conditions for practicing evaluations is not so different from how you might approach (or teach) someone who is learning a new movement skill. The complex skill, either movement skill or orthopedic evaluation, must be broken down into its component parts and each part practiced to the extent that it is performed correctly. Here are three key areas for optimizing your evaluation practice (and how checklists can help):1. Break Down The Evaluation into “Sets and Reps” 1st “Parts” Practice > 2nd “Whole” Skill Practice

“Practice” the way you want to “Play”

The Fundamentals Must Be Automatic Before You Get Fancy

As clinicians, I think there is a natural desire to want to feel the state of “Flow” early on- that everything is clicking and you are utilizing a unique combination of scientific “truths” and intuitive judgments in your evaluations. But, flow and mastery take time to develop. So, I would argue that as you are starting out, the number one priority should be to make your evaluations as consistent as possible- almost to the extent of feeling “boring” or rote. This idea, I think is well expressed by famous psychologist, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who coined the term “Flow” (4) and is author of the book: “Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention” (3). In this book, he writes,“You must first learn your craft and then set it aside.” I’m off to practice my evaluations… -Leda McDaniel, SPT Please Visit Her Website For Examples Of Her Orthopedic Evaluation Checklists Leda is a current Doctorate of Physical Therapy (DPT) candidate at Ohio University and upon graduating in May 2019 is interested in working with orthopedic patients with chronic pain. Leda recently published a book about her experience of personal recovery from chronic pain, which you can find on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/069212120Xref_=pe_870760_150889320 You can also find her blogging at: https://sapiensmoves.wordpress.com/ References:

|

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed