- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

Static and dynamic postural assessment are important components of my physical examination. Static postural assessment cues me into what dynamic postures I want to evaluate. The most common spinal postural deviations I see clinically are lumbar lordosis, kypholordotic, swayback, and flatback postures. Of those four, increased lumbar lordosis is the most common postural problem in my outpatient population. In this post, I will break analyze the lordotic posture and give a few assessment suggestions.  Background & Biomechanics Individuals with lumbar lordosis will have relatively tight hip flexors, rectus femoris, erector spinae, tensor fascia latae, and plantarflexors. This line of muscles running from posterior to anterior is generally thought to be strong and facilitated. On the contrary, the rectus abdominus, transversus abdominus, obliques, gluteus maximus and gluteus medius are all relatively lengthened and inhibited. In addition to muscle changes, there is increased pressure on the anterior lumbar vertebral bodies, adaptive shortening of the posterior lumbar ligaments, and relative narrowing of the intervertebral foramen. Patients will often have the greatest stress placed across L4-S1 segments. It is important to note that understanding the biomechanics is only as important as understanding the movement dysfunction, patient's pain science, and how to appropriately prescribe corrective exercise. Assessment & Treatment

Due to the increased lumbar lordosis, patients will generally have difficulty maintaining a neutral core during functional movements. Additionally, they will have difficulty isolating their glut muscles due to over facilitation of the lumbar paraspinals or hamstrings. Based on the patient's occupation and daily requirements, it is important to look at both the upper and lower extremities when treating spinal dysfunctions. A few quick clinical tests you can perform to assess for abdominal control are as follows: 1) Standing Hip Extension test: Have the patient perform hip extension from a standing position. If the patient is unable to move into hip extension without excessive lumbar movement, they lack lumbopelvic rhythm. Individuals with lumbar lordosis will generally initiate hip extension from the lumbar spine. Turn this test into a treatment by performing the same movement with specific cueing. 2) 180 degree shoulder flexion test: Have the patient raise their arms overhead fully and see how the core responds to the movement. Generally, the patient will over-extend their lumbar spine creating a hinge point in the low back. 3) Straight leg raise : Have the patient raise 1 leg into the air and assess for core stability. The patient will often hyperextend their low back secondary to core insufficiency. These 3 assessments are only a few of the many assessment and treatment tools we teach in the OPTIM COMT and Fellowship programs. Don't forget to check out TSPT Insider Access Page for exclusive information! -Jim

1 Comment

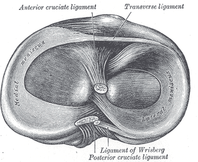

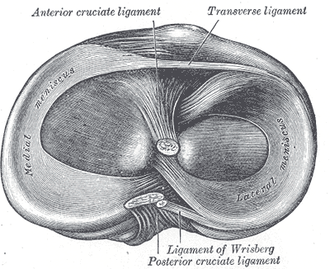

Last week, I wrote about the importance of assessing segmental mobility, even with the lack of evidence for our ability to do so. Some of the research says segmental mobility and SIJ assessment have both poor inter- and intra-rater reliability, suggesting we shouldn't waste our time with it. This can be detrimental to the patient as the slight differences may be important for directing our treatment. As I've said before, without these kinds of assessment skills, diagnoses like a fallen cuboid may be missed. Even if the research hasn't been supportive of our abilities to do segmental assessment, we shouldn't give up on our efforts to find a more effective method. Could the lack of support be due to lack of training in standard physical therapists? Lachman's test requires the therapist to notice a difference of a couple millimeters in order to assess the integrity of the ACL, yet the test has extremely high diagnostic accuracy. Why is it we are presumed to be able to notice these small differences and not others? It is likely due to a lack of training. Physical therapists out of school are used to assessing joints with large amplitude forces that blow through one joints available range and moves into another - negating the findings typically. The smaller differences may play a larger role. I returned to this topic, yet again, because of a recent discussion I had with some physical therapists in Optim's online mentoring program. Between each course we have several sessions where the participants present a case they have been working on and feedback is given from the mentors and other classmates. One of the issues during the early stages of the COMT program is that there isn't a consistency in assessment between all the therapists. One clinician may list hip and knee ROM as WNL (within normal limits). While this may be true, the therapist may have not been thorough with their exam and missed some subtle differences that may impact treatment. For example, when treating knee pain, often there is a loss of just a couple degrees of knee ext on the involved side that if treated appropriately, may completely eliminate the pain. The same applies to every joint, especially when considering treatments like repeated motions or manipulations. I don't typically use a goniometer in my measurements because I feel like I focus too much on aligning the arms and stop paying attention to the actual motion. The most important finding in my opinion are those small asymmetrical losses of mobility, as it can be the key to your treatment. -Chris

Like this post? Then check out the Insider Access Page for advanced content! And check out similar posts below!

Segmental mobility assessment is a technique that is taught in school, but at a very basic level. Not much time or reasoning is put into it, so new graduates have difficulty seeing value nor identifying noticeable differences with it. I've written before about how advanced manual training allows clinicians to become more precise with the segmental assessments and how new grads typically assess too large a range, leading to inaccurate assessments. This unfortunately has been discredited with studies saying we cannot be precise with our manual skills, however, these studies typically just use "experienced clinicians" and not clinicians with advanced manual training. I decided to return to this discussion after one of Optim COMT's mentoring sessions last night. One of the participants asked what the point was in trying to identify the source of the symptoms. In our program, we like to present a variety of approaches, which includes repeated motions and a standardized mobility exam. The techniques can be an incredibly useful tool in facilitating a thorough examination and effective treatment. That being said they may have limitations and being able to identify a segmental component may be essential to getting the patient 100% better. For example, many standardized exams to not look at the foot/ankle more than gross AROM. Without segmental assessment, a fallen cuboid may be missed and without manipulation will not improve. In no way am I saying to ignore the benefits of standardize exams and repeated motions as treatment, but you will likely have patients that do not respond to these global approaches. Even though some research says we cannot be specific with our assessments or manual treatments, there is something to be said about trying to narrow your range of effect to the region of restrictions. For example, likely hypomobility will be noted in the CT junction, but we may not be able to find the exact segment. However, if we just look at cervical extension and ignore any segmental assessment at all, we may end up mobilizing a hypermobile region, which can lead to worse symptoms. Don't be so quick to disregard the potential benefits of manual segmental assessment and determining the affected structure, it may play a role in getting the patient 100% better. -Chris

Like this post? Then check out the Insider Access Page for advanced content! And check out similar posts below!

Imagine a 65-year old patient walks into your clinic with medial sided knee pain. He reports an insidious onset of pain that increases after rest and decreases with movement. Assuming he does not present with any red flags, this patient likely has knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis is a breakdown of the protective cartilage surrounding synovial joints. The knee joint contains fibrocartilaginous meniscus and the articular cartilage surrounding the joint surfaces. In osteoarthritis, there will be a breakdown of both types of cartilage. As a clinician it is important to understand that a patient with OA will also have degenerative meniscal tears. This individual likely does not need a meniscal surgery, they need lower quadrant strengthening and mobility exercises. Conservative management of cartilage defects is challenging. Cartilage has poor vascular supply which does not aid the healing process. Movement is the ideal method of healing for cartilage. As the PT, our job is to gradually reintroduce joint loading to the injured tissue. This can be done through muscle contractions and gradual weightbearing. Individuals with cartilage defects should be performing 1,000's of repetitions at ~15% of their 1RM. In other words, low resistance/high repetition interventions are the best. Examples of low resistance/high intensity include the bicycle, total gym (vigor gym), unloaded treadmill, and seated tailgaters (passive knee swings). Early in the patient's plan of care, you want to train in the pain free region as much as possible. The patient should not leave the clinic in more pain than when they come in.  Recommendation for Treatment for someone with Degenerative Knee Meniscal Pathology: 1) Manual therapy to address joint hypomobility 2) Corrective exercises to address any positional faults 3) Strengthening the hip and ankle musculature 4) Education on cartilage damage and how to rehabilitate the tissue* 5) Aerobic machines for high repetition, low resistance exercise- Thousands of repetitions at 15% 1 RM. 6) Retraining poor functional movement patterns (squat, lunge, SL balance) *Education includes the necessity to perform these repetitions throughout the day also. If able, the patient should be going to the gym an riding a stationary bike for long periods. As always, let pain and the patient's response to treatment be your guide before progression. -Jim  Final days to apply for the OPTIM Manual Therapy Fellowship Program in Houston, Texas. The first course is this coming weekend Nov. 14 and 15, 2015 & will include a unique opportunity to get back into the cadaver lab to relearn upper quarter anatomy. If you're looking to join the Houston cohort, there is still time left. With OPTIM, you can expect a residency-like learning experience without breaking the bank, all while learning from highly skilled physical therapists. Check out optimfellowship.com for more information! Please email OPTIM if you are interested!  Last week I woke up one morning with significant knee pain on the L side. I hadn't exercise or done any new activity the prior day. I simply woke up with knee pain. The pain was primarily located medially and was increased with any twisting or flexing of the knee beyond 90 degrees. It's one of those occasions where it is good to be a PT, because you can treat yourself and do so quickly! The typical presentation may lead some to think meniscus tear. While I believe I have meniscus tears in both knees, I think they are asymptomatic and I have had them for years. The fact that there was no mechanism of injury should lower meniscus as your diagnosis as well. Typically if I were to have an evaluation like this, I would check the spine and neural tension immediately even if I suspect local involvement. However, for myself I went straight to the knee due to rapid improvement. The significant findings were lack of knee flexion mobility, maybe a slight loss of end-range knee extension, but the most significant findings was decreased tibial IR on the symptomatic side. You can assess this with the patient seated by having them actively (or you perform passively) tibial IR (watch out for ankle inversion!). Often you will notice a loss of mobility on the involved side.

Like this post? Then check out the Insider Access Page for advanced content! And check out similar posts below!

Are you currently performing spinal thrust manipulation in the clinic? If you answered no, why not? We asked this question at our first OPTIM COMT program two weekends ago. Aside from a lack of experience performing the techniques, a main reason physical therapy clinicians are not manipulating is because of potential complications associated with manipulation. In this post, I will analyze the true risk associated with spinal manipulation and how safe these techniques truly are with appropriate screening.  Cervical Manipulation Risks Cervical thrust joint manipulation is often viewed as a danger zone by physical therapists. For whatever reason, physical therapy schools avoid teaching cervical manipulations. In school the negative complications are ingrained in our minds. The greatest risk associated with cervical manipulation is inducing vertebral basilar insufficiency (VBI). VBI is defined as an occlusion or injury to the vertebral artery causing a decrease in bloodflow to the brain stem and posterior cranium. If the vertebral artery is affected, stroke or death could result. In addition to VBI, other adverse reactions can include neck soreness, radiating arm pain, nystagmus, headaches, ringing in the ears, and other less severe complications. Risk by the Numbers: What the Research Reports The exact risk of severe complications (VBI or death) is unknown. Rivett and Milburn estimate that 1 in 50,000 to 1 in 5,000,000 manipulations will result in neurovascular compromise (1). DiFabio et al performed an extensive literature review of 177 patients who experienced severe adverse events following cervical manipulation. Of the 177 patients, arterial dissection (VBI) was the primary diagnoses found. Additionally, DiFabio pointed out that only 2% of the severe injuries were performed by physical therapists (2). Others have reported the risk of VBI following cervical manipulation to be as high as 6 in 10,000,000 (3).

Conclusion The research suggests that severe adverse responses to spinal manipulation are extremely low. As physical therapists, we receive extensive training to assess for VBI and cauda equina syndrome. With a thorough subjective history and objective examination, you should be able to determine if the patient is appropriate for manipulation. If you find that the patient is demonstrating signs and symptoms of cauda equina or VBI, refer back to the appropriate medical provider. Stronger evidence on the benefits of spinal manipulation is emerging every year. If the patient is appropriate, we should be performing these techniques. If you do not feel prepared to perform these techniques, find a good manual therapy program to learn them! Let me know if you have any questions, Jim References:

1. Rivett, D.A., Sharples, K.J., & Millburn, P.D. (1999). Effect of pre-manipulative tests on vertebral artery and internal carotid artery blood flow: A pilot study. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, 22, 368-375 2. Di Fabio, Richard P. "Manipulation of the Cervical Spine: Risks and Benefits."Physical Therapy 79.1 (1999): 50-65. 3. Coulter ID. Efficacy and risks of chiropractic manipulation: what does the evidence suggest? Integ Med1998;1: 61-6 4. J. D. Childs, T. W. Flynn, and J. M. Fritz, “A perspective for considering the risks and benefits of spinal manipulation in patients with low back pain,” Manual Therapy, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 316–320, 2006.  OPTIM just got word from the American Board of Physical Therapy Residency/ Fellowship Education that it is now an APTA/ AAOMPT- accredited manual therapy fellowship program. OPTIM was granted this prestigious accreditation for the next 5 years. OPTIM can now bestow the credentials of Fellow of the American Academy of Orthopedic Manual Physical Therapists (FAAOMPT) on our program graduates. A few words from OPTIM owner Dana Tew PT, DPT, OCS, FAAOMPT: "Big thanks to all of those that believed in us, and even those that didn't. Thanks to the folks who had confidence in us to start the program, trusting us to make this happen, and all of the mentoring and feedback along the way. The amount of effort and time that it takes to reach this milestone is proof of how strongly we believe in post-professional education and moving our profession forward." There are now 25 accredited programs in the U.S., but still less than 1% of PT's have earned the privilege of using the fellow designation. OPTIM is now honored to help raise the bar on physical therapist education. Congratulations OPTIM! Please like and share this post to show your support for OPTIM Physical Therapy!  We have previously gone over many methods and indications for utilizing repeated motions, especially pain and mobility. Something that can be overlooked however is the effect it can have on muscle strength. I recently had a patient who I was treating for "hip OA." As is typical, the patient actually responded well to repeated lumbar extensions, improving her hip mobility, strength and pain. It wasn't until a couple weeks later the patient reported she experiences "drop foot" after walking approximately half a mile and it had been going on for years. I instructed the patient to perform her repeated extensions before her walk. The following appointment she reported no drop foot at all. There are a couple things that I want to review here. First, while it is important to do your repeated motions HEP hourly (or more!), it is essential to perform them prior to any "fitness" training. The activities challenge our bodies more than normal, so our deficits can become more pronounced typically. I used to experience my sciatic neural tension only when running, but it could be prevented with sideglides. If we don't try and reset our bodies prior to exercise, we may actually be reinforcing the dysfunction. Second, never dismiss our potential effectiveness in treating chronic injuries. You will encounter patients that have been experiencing a pain, or in this case a weakness, for decades that become fast responders to repeated motions. Finally, a weak muscle may not be secondary to local atrophy. Pay attention to muscles that don't seem to improve in strength. Muscles may test weak only because of spinal inhibition. Whenever you evaluate a patient with an extremity deficit or pain, check for spinal mobility restrictions as a sign for potential contribution. -Chris

Like this post? Then check out the Insider Access Page for advanced content! And check out similar posts below!

|

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed