- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

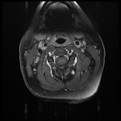

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

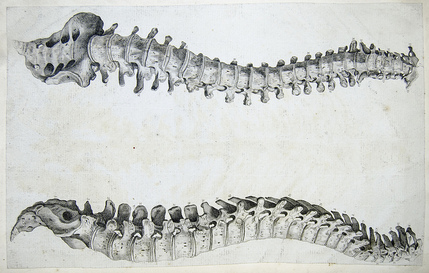

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

|

As many of you know, we recently launched a Home Exercise Portion to our website. They consist of many exercises that we prescribe and programs like VHI don't contain. I wanted to highlight one exercise today, the Quad Rock Back, because of all of uses for it. The exercise is a staple of the Shirley Sahrmann philosophy. While it is listed under the "Low Back" section, it is often prescribed for cervical, shoulder, and hip patients as well. We will break down how the exercise can be used for each region. As described in the video, when this exercise is performed for cervical patients, often the head begins to extend or flex while rocking back. This is a result of abnormal movement and compensatory patterns in the cervical spine. For cervical spine patients, we encourage a chin tuck so that no neck movement occurs during the rocking.

There are many reasons why I like to give this exercise to shoulder and hip patients, one being joint compression. We are taught in our manual therapy classes that joint compression can be beneficial for healing; it also can help mobilize the posterior capsule. It also helps mimic the developmental patterns of weight bearing on the upper extremities, and thus is a critical part of rehabilitation. Additionally, the quad rock back exercise can be use to help normalize scapulohumeral movement patterns and avoid any compensatory activity. While performing the exercise, the movement can be completed by actively flexing the hips, instead of pushing away with the UE's. This allows the shoulder to move in a more normal pattern. Similarly, the exercise can help with unwanted hip musculature activity. By reversing the directions (instructing the patient to push with the hands and not actively flex the hips), the patient can decrease abnormal femoral head sliding and thus compete hip flexion less painfully. The exercise can be used both for treating and assessing and low back dysfunctions, and not just because it is one of the more comfortable positions for low back pain. If you take your patient into quadruped and have them rock back, pay attention to the pelvis, hips, and low back. You may note a deviation to one side, suggesting increased muscle activity, stiffness, or movement patterns. Often you will note premature lumbar flexion compared to end-range hip flexion. This is secondary to all the sitting we do throughout the day - our lumbar spine becomes more flexible compared to the hip! By encouraging the patient to maintain a stable lumbar spine while rocking back (this can be done by placing a stick across the low back - if it falls off, we know there has been abnormal movement). This teaches our patients to isolate hip movement from back movement. While I may not subscribe to all of Sahrmann's theories on movement impairment syndromes, especially in the acute phase, I do appreciate the focus she places on changing compensatory patterns with her exercises. Many of these patterns stem from abnormal postures or repetitive tasks that we perform throughout our daily lives. The rehab focuses on resisting any changes in movement that occur as a result. I have found that I get better results with incorporating repeated motions into my treatment, but I continued to use Sahrmann exercises to try and retrain movement afterwords. -Chris

1 Comment

A few weeks back Chris wrote a great post on Sequencing Your Treatment Session. His post focused heavily on manual treatment and the importance of checking and rechecking your asterisk (concordant) sign. This post is intended to be a quick and dirty outline regarding how to prioritize interventions from start to finish. Not all apply to every patient, but knowing the sequence is fundamental.

1) Brief Subjective/Objective Recheck: This should be viewed as a mini-reassessment. Was there any change in symptoms since their last visit? How did they tolerate the their HEP? How did the patient respond 24-hours after the last treatment? Objectively, are the same restrictions and movement impairments present? 2) Manual Therapy: During the objective, you likely found a joint restriction or movement pattern that needs correcting. Perform the necessary manual techniques and re-check your asterisk sign. 3) Corrective Exercise: Performing corrective exercises immediately following manual therapy will maximize the patient's ability to find and recruit muscles that were previously not recruiting normally. 4) Functional Warm-up: The warm-up should increase core temperature targeting the muscle groups that are dysfunctional. Examples: bicycle, total gym, elliptical. 5) Power Exercises: Incorporate power/ plyometric exercises following the warm-up when the muscles are not fatigued. Since form is essential during these exercises, performing them while the muscles are fresh is very important. It should be noted that not all patients will be ready for power-type exercises during their first few visits. 6) Strength Exercises: Strength exercises include those performed in the 4-8 repetition range, 3-4 sets with 2-3 minutes of rest between each set. Similar to power, not all patients can tolerate pure strengthening early on. Many times patients require a few sessions of neuromuscular re-education and form re-training prior to pure strengthening. 7) Conditioning and Endurance: Often we find ourselves going directly to this stage following a functional warm-up. Since pain and movement impairments our the primary focus early on, performing conditioning or retraining exercises is acceptable. The dosage of these exercises is typically 3 sets of >10 repetitions with less rest in between sets. A main focus is on proper form and controlling the movement throughout the ROM. 8) Warm Down Appropriately structuring a treatment session is a key component to the patient's success. One question you need to continually ask yourself: "how do you dose pain?" There is no perfect answer. Pain generally leads to muscle inhibition and form breakdown which often categorizes the patient in the conditioning and retraining exercises section. As your patient progresses it is essential to perform the exercises in an appropriate order to maintain form and maximize gains throughout the session. -Jim The last month or so I have been using repeated motions consistently in my evaluations and treatments. Like many other PT's, I was taught McKenzie in school basically was lumbar extensions and only applied to a select few patients. The misunderstanding of how repeated motions work and should apply to our patients is probably one of the most significant disservices we are doing to our patients. Since incorporating them into my care (thanks to The Manual Therapist), I have noted significantly greater improvements in less time. Now I do not have a full understanding of the system based on MDT, but this post will link to several posts by The Manual Therapist so you can learn to apply it tomorrow. Let's start of with why you should be using repeated motions in your exam. With about 90% of our patients being rapid responders, we should be getting immediate improvements on the day of our examination. Repeated motions are easy, reliable, have built in testing, lead you to treatment and give you your HEP. You will notice with application of these principles, for the appropriate patient you will be amazed at how much better your patients get faster. Now what exactly is that about MDT and repeated motions that makes it so effective. Let's start with some of the misconceptions about MDT. MDT does benefit from some manual techniques. While I like repeated motions because it makes the patient more independent and gives them their HEP, sometimes they are unable to get the patient 100% of the way there. A manual technique may get that extra bit or may even accelerate improvements in another area. The MDT theory is not based on disc model like what is taught in school. With modern pain science showing how much force is required to deform tissues and how much normal degeneration solidifies different tissues, we must realize that we are not actually affecting the disc. These "disc" injuries are often associated with McKenzie extension exercises, leading to the stereotype that MDT is extension. This couldn't be further from the truth as repeated motions can be applied to any direction and any joint (the link there has a video that shows various resets for repeated motions at different joints). So how are the changes acquired with MDT? One of the prime components of why MDT works (per one hypothesis) is because the repeated loading of the joints engages mechanoreceptors enhancing proprioception. This may alter the patient's perception of their ability to go into what was a painful motion. What is necessary for repeated motions to actually work is to actually get to end range. We all have seen mobilizations and manipulations have improvements with our patients. There are different theories as to how these changes actually occur, but one of the necessary components is that end-range is required. Repeated motions have the benefit of making the patient independent with their care and allows a patient to maintain any gains acquired from PT. We may not improve ROM in all patients due to degeneration, but pain or other symptoms can still improve. It is often difficult for patients to get to this end-range out, because more often than not the direction that is prescribed is the painful one. With each motion in the correct direction, the patient will realize that it is okay to move into that direction and lower their fear avoidance. How do we choose which direction to proceed? The treatment choice is based on the directional preference. The directional preference is the direction that a joint needs to be repeatedly loaded to have effects potentially on ROM, pain, DTR's, strength, and function. The direction is more often than not the direction the patient tends to avoid. When trying to find the directional preference for sure or when distributing a repeated motion as part of an HEP, it is essential that you remember the stoplight system. The stoplight system allows you and the patient to monitor the progress of symptoms ensuring the correct exercise was given. A green light is when the symptoms centralize and remain better. It is still a green light if the pain centralizes but increases centrally, because it is still centralizing! A yellow light is when a patient's pain or symptoms increases but they can "walk it off." What we must realize with yellow lights is that maybe a patient's pain will increase, but in doing so they have greater motion or greater motion before the pain occurs. It is easy to become hesitant with yellow light responses, but we must remember that we need to get to end-range to have the desired effect. A red light is when a patient's pain or symptoms worsen but cannot be "walked off." Hopefully this helps to summarize some of the concepts of repeated motions and MDT. I encourage you to look at each one of the links for further information and better understanding of repeated motions. For more information, check back on Dr. E's blog regularly in order to enhance your understanding in the area. He often has posts like this that may show you how to incorporate MDT into your clinical reasoning. In doing so, you likely will notice rapid improvements with many of your patients. -Chris  In most physical therapy schools, including ours, McKenzie method is glossed over and, for the most part, summarized as "extension exercises." We are taught that sure it works great, but only for a small subset of populations. While some of the research may support this notion, it appears there is more to McKenzie method than the literature reveals. I recently have watched numerous video's on The Manual Therapist's channel that showed rapid changes using McKenzie method. It is more than just repeated motions. There is a necessity of reaching end-range and a clinical reasoning behind how the patient's symptoms change with the repeated or sustained motions. The Manual Therapist had a guest post recently that discussed 5 key things for understanding and implementing McKenzie. Odds are several of these topics will apply to more than McKenzie method.

Next, I recommend a reassessment of the structures that were targeted during the initial evaluation. For example, if I found decreased mobility of the AA joint on the eval day, I would definitely be sure to reassess that prior to performing a manipulation - if warranted. With daily activity, joint mobility, flexibility, etc. can easily change due to something that happened between treatment sessions. And if a previously hypomobile joint is now normal, why mobilize it? Now I am not saying we should perform a complete re-examination of the objective section, but if the plan for the day involved manual therapy, I recommend assessing the targeted structures first. In cases like SIJ Dysfunction, maybe you reassess the pelvic alignment each session. How thorough you need to be is determined by dysfunction location, severity of injury, and various individual patient factors.

After finding the dysfunctional areas of mobility, I typically perform my manual therapy. My goal is to give the patient as much mobility in the limited structures as possible to the norm. Any limitation can lead to a compensation of hypermobility in adjacent or distant structures that may be the source of the pain. With the sedentary aspects of our lives, degeneration has become an expected normal development. While we would like to acquire true normal motion in everyone, it is not always feasible. I should note that some clinicians may prefer the patient do a warm-up prior to manual therapy or the reassessment as that may have an impact on treatment performance and clinical findings. Personally, I determine the need of a warm-up based on each individual patient. (I also should note not every patient requires manual therapy). Once I have completed my manual therapy, I go back to reassessing. Is the previous hypomobile joint now hypermobile? Is the previously painful motion or action now pain-free or less painful? We need to be certain our manual therapy had the desired outcome. As Nick Rainey states in a previous guest post, this is know as an asterisk sign (test-treat-retest). We may find that our previous assessment was inaccurate or that we need to spend a little more time with manual therapy in order to reach our goal. It is at this time that I proceed to therapeutic exercise/neuro re-ed. I truly believe it is important to complete your manual therapy first before moving this stage. With manual therapy, we often acquire new ranges of motion due to changes in joint mobility/tissue length/neural tension. While this is important, it is essential we use exercises to lock in the changes. We must retrain the body to move in those new ranges; otherwise, we are setting the patient up for re-injury. As Gray Cook has said, our bodies adapt dysfunctions often as a form of protection. If you free up the dysfunctional tissues, you are putting the patient at risk. Finally, I recommend finishing up each treatment session with another subjective portion. See how the patient immediately responds to that day's work. Some treatments have an immediate effect and again can impact our plan for the next session. As is typical, every patient is different and may require a different sequence for the treatment. This is merely an outline of how I work with my orthopaedic patients typically. There are more than a few indicators for adding, subtracting, or re-ordering the plan for that day! -Chris  I have had a few "higher level" patients in the past few weeks and one consistent trend I found in my practice is that I have been progressing them too quickly. I am not exactly sure why this in the case. Both groups of people present with the same impairments so why would I treat them differently? My assumptions are that I do not want them to become bored with a basic HEP or maybe because they are starting at a higher level they should require higher level exercises. Both of these are fallacies. Despite starting from a higher functional baseline the higher level patients presented with similar impairments as the low level patient. A 3+/5 muscle grade is a 3+/5 no matter how you look at it. For example, with a low level patient, I gave the clamshell exercise to strengthen the posterior gluteus medius. For the higher level, I gave the clamshell exercise in a modified side plank position. Both exercises target similar muscle groups, but the higher level exercise is much more demanding across the entire system. I have given similar exercise prescriptions like this is the past and consistently found that the patient returns to the clinic performing the exercise improperly or having pain while performing it. Lessons Learned: 1. A weak muscle is a weak muscle regardless of what type of patient you find it on. 2. Start basic. In my example above, I added side planks to a clam exercise during the initial HEP. When prescribing this, I made sure the patient had adequate abdominal control, but it took away from the true target of my treatment. The primary impairment was gluteus medius weakness. I needed to start in the least aggressive position and isolate the glut medius. 3. Educate appropriately. My assumption is fairly true in that higher level patients get bored easily with low level exercises. This patient population is used to performing strenuous exercises. Generally, despite being in pain, they want to perform something hard. As a therapist, educating them on the importance of the low level exercises and discussing the exercise progression in future visits will allow for more patient buy-in to your treatment. Do not be afraid to start at the most basic level. You are the expert and you no why they need to start at that level. -Jim  I performed 3 evaluations yesterday morning. The first individual has been having cervical pain since a MVA in 1991, the second low back pain since her first child 7 years ago, and the last individual was having bilateral radicular symptoms for the past 6 months following a discharge from the military. All 3 can be defined as having chronic pain. Knowing their duration of symptoms alone, how does this change my plan of care? How does it change my prognosis? What sort of goals need to be set between the patient and I? When a patient presents to you with pain for >6 months, they often are having pain in multiple joints. This makes sense from both a biomechanical and cortical reorganizing perspective. Biomechanically, if an individual is having pain, they will often start to move more from other body regions to avoid pain. These abnormal movements cause repetitive microstrains and result in pain as well. Additionally, individuals with chronic pain will posture themselves in non-painful positions throughout the day. You will often see them in a guarded, fearful posture. Looking at chronic pain from the cortical level, many changes begin occurring in the cortex in the presence of pain. Cortical smudging occurs and other areas of the brain become activated in the presence of pain. Some of these other areas are those associated with cognitive functioning and emotion so you can imagine how the pain completely envelopes their life. As you can tell already, there is no magical solution to treating these patients. But good approaches include using graded exercises, addressing all barriers that will prevent them from succeeding, and creating realistic and specific goals to measure success. Graded exercise is essential because many of these people STOP exercising in the presence of pain. We see them completely deconditioned, making it difficult to distinguish between true tissue pain or simply the aches and soreness associated with starting a new exercise routine. Start small and start slow! For example, as part of their HEP, I gave one of these patients a home walking program (based off the results of their 6 minute walk test): Walk 4 minutes, 3x/day. Yes, it seems simple, but it is realistic! Barriers also need to be addressed. Typically if someone has been having pain for ~20 years, they have tried to seek care elsewhere but it has been unsuccessful. Why is it unsuccessful? Maybe the musculoskeletal pain is not the only factor. You need to determine if they have financial barriers, transportation issues, psychological issues, social barriers, and more (all of this is obtained during the subjective interview, but gathered much more throughout subsequent visits as you develop a relationship with the patient). Finally, realistic goals must be set. If someone believes they have 10/10 & have been having that pain for 7 years, completely eliminating their pain is not a realistic goal. You need to determine what the patient wants to achieve and set obtainable goals with a set time frame. As you can imagine, adherence and compliance with therapy is another huge problem. Throughout these treatments, education is KEY. Sometimes it may feel that we turn into psychologists. This is partly true, but I say we have a little more power than them. Our research shows that graded exercise is beneficial for individuals with chronic pain. We can spend 1 hour listening to and educating the patient while having them exercise. Early in the treatment you may be taking on a "general exercising and conditioning" approach. This is fine! Stick with it and you will likely find you are often successful. -Jim  Dosage is one of the most important factors to consider when prescribing an exercise. This decision is often made based off level of acuity, tissue type, anatomical location, patient age, and more. In school, one learns the general principles of exercise prescription, but what is often neglected is WHY you prescribe in certain ranges. "Mechanotherapy: how physical therapists' prescription of exercise promotes tissue repair" is a 2009 article published in the Journal of Sports Medicine that elaborates on this topic. Physiologically, what stimulates tissue repair of articular cartilage, muscles and tendons is a term called Mechanotransduction. In this article Mechanotransduction is defined as "the process by which the body converts mechanical loading into cellular responses." This can be thought of in clinical terms as what is occurring at the histological level to allow one to prescribe a certain exercise dosage without increasing the risk of injury. Mechanotransduction can be broken down into 3 phases: 1) Mechanocoupling: This is the physical load cells undergo while in repair. The physical load is transferred into chemical signals which stimulate cellular changes. 2) Cell-Cell Communication: When one cell is stimulated, other cells in the area (whether directly stimulated by the initial mechanical stimulus or not) will undergo a cellular response. 3) Effector Response: When a cell is mechanically stimulated through compression, distraction, etc., several processes will occur intrinsically to allow change to occur. Now knowing each of the 3 stages, you must think about them in relation to the Type of Tissue involved to understand how that tissue heals. Tendon Healing: When a tendon is trying to heal, there is up-regulation of insulin-like growth factor, other growth factors, and cytokines which allows for cellular proliferation and tissue remodeling. Because healing is occur at the cellular level, too much stress OR too little stress on the tendon tissue could cause an alteration in the up-regulation, not allowing the tendon to rehabilitate optimally. The research up-to-date shows that tendons responds positively to "controlled loading." Research focusing on the type and intensity of controlled loading (eccentrics, assisted, resisted) is still ongoing. Muscle: The authors Khan and Scott state that "muscle offers one of the best opportunities to exploit and study the effects of mechanotherapy" because of how muscle tissue responds to loading. We know there is an overload of mechanogrowth factor (MGF) released when load is induced on the muscle force. This in turn causes muscle cell hypertrophy due to a cell-to-cell communication with nearby satellite cells. At this point, the research shows that early loading after a brief immobilization period is essential for minimizing atrophy and restoring normal cellular structure of the muscles. Articular Cartilage: Articular cartilage is comprised of a large population of mechanosensitive cells. It is hypothesized that by repetitively stimulating the articular cartilage with a low load/high repetition exercise dosage, better outcomes will result. One study assessing full thickness cartilage defects following periosteal transplantation demonstrated that individuals who used continuous passive motion (low load/high repetitions) had greater outcomes than those who did not receive this intervention. As with all things, research is ongoing. Bone: When assessing bone healing, osteocytes are the primary mechanosensors. A recent study looking at individuals following a distal radius fracture had stronger bone growth if they received intermittent compression as an adjunct to the standard of care (compression & gripping exercises). The pneumatic compression allowed for extra stimulation of the bone cells and an increased healing rate. We know parts of this article are dense, but understanding what is occurring at the cellular level can greatly change your viewpoint of how various tissues heal. Through each of these tissues we can see that Mechanotherapy plays a unique role in healing of different tissues types. The healing of osteocytes differs from that of chondrocytes which differs from myocytes. It is fundamental to understand these differences in order give appropriate doses during exercise - just as it is important to know the tissue type you should be treating following your examination. As a general rule of thumb: Articular Cartilage: Low Load, High Repetition; ~15% 1 RM; Thousands of repetitions. Tendon: Controlled Loading; consider eccentric exercises, but do not overload the tissue. Muscle: allow for a brief period of immobilization to restore homeostasis following injury. Bone: Based on location of the fracture, consider adding compression to your treatment to improve rate of bone growth and decrease healing time. References:

Khan and Scott. (2009) "Mechanotherapy: how physical therapists' prescription of exercise promotes tissue repair." British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2009; 43: 247-251. Web. 5 Dec. 2013.  This editorial was brought to me during my residency at Harris Health. It is written by Jason Silvernail on the website SomaSimple. As therapists we often deal with 2 types of pain: Chemical and Mechanical. Understanding the difference between the two is important because it allows you to explain to your patients "why" they are experiencing pain. Chemical Pain is associated with inflammation, and responds positively to anti-inflammatory medication and rest. Mechanical Pain is more complex! It is due to prolonged pressure or tension on nervous tissue. When you see a patient with mechanical pain, they may have questions regarding why their MRI did not show anything significant OR why their medications are not working. This is because Mechanical Pain is due to how the tissue feels, and not the way the tissue looks. There is no acute inflammation and no acute tissue damage. Mechanical pain is a chronic irritation. To fix mechanical pain, we need prescribe movements that relieve the tension that is being placed on the nervous system. This specific movement will gradually or immediately allow the patient to experience less pain. The patient needs to be regularly reversing the postures that are placing tension on their nervous system. This is where doing your Home Exercise Program regularly becomes so important. Sometimes it can be difficult to tell a patient to MOVE when they are in pain, but by educating them that the specific exercises you are prescribing are actually taking tension off the involved structures can be a great for compliance. The last point I will touch on is how many sets and reps should be prescribed for mechanical pain. As therapists, we know how many repetitions to prescribe for strength training, neuromuscular re-education, and power, but how many reps do you prescribe for pain? The answer is unique to each patient and will vary based on comorbidities, irritability level, etc... I would recommend starting with a high repetition, low load dosage. This will minimize the risk for compensations, decrease the risk of increasing symptoms, and hopefully get the patient performing them more frequently. Reference:

Silvernail, J. "Understanding Mechanical Pain." Somasimple.com. Web. 14 Dec. 2013. 23 1/2 hours is a short video by Dr. Mike Evans regarding the BEST intervention for patients of all diagnosis'. He assessed risk factors such as drinking, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, and more. After years of research, he found one intervention that was the single most important thing you could do for your health. The video has some great information for you as a health care practitioner, and also can be used as a teaching tool for your patients. |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed