- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

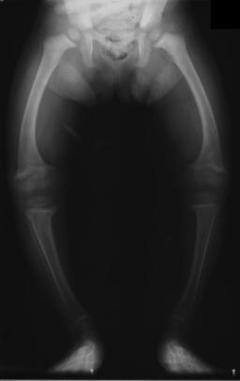

We were recently asked about treatment methods for genu varum of the knee, so we thought we would do a little literature review on the subject. We believe the request was directed towards an exercise-based approach. Unfortunately, we were unable to find much evidence regarding treating genu varum with exercise. With genu varum, the line of gravity runs farther medial to the knee than normal, putting increased stress on the medial compartment of the knee. This puts the individual at risk for developing OA. Due to the increased risk in developing unicompartmental osteoarthritis, it is desireable for the patient to restore normal alignment in order to delay the need of having a Total Knee Replacement. There are several methods of managing genu varum right now, which we will briefly review. The traditional method of treating genu varum involved an osteotomy of the proximal tibia with the goal of restoring normal knee alignment. Goutallier et al found a desirable range for realignment: 3-6 degrees of valgus. At < 3 degrees of valgus, individuals developed recurrent genu varus, while at > 6 degrees of valgus, individuals developed deterioration of the lateral tibiofemoral joint. A newer method that is currently being developed is known as the llizarov method (Park et al, 2012). During the osteotomy, the surgeon also places an external fixator on the patient. This allows gradual adjustments to be made to the knee alignment during the 24 weeks it remained on. While the method was able to restore normal alignment to the knee, there was a high level of complications to the patients. An alternative method of treating genu varum includes bracing and heel wedges. The brace under discussion is called a compartmental unloader. An individual with genu varum would want a valgus orthosis. It functions by either having a valgus stress built into it or the ability to develop the stress while donning the orthosis. With the valgus stress placed on the knee, the natural varus moment decreases, lowering the stress on the medial tibiofemoral joint. This hopefully delays the need for a Total Knee Replacement. Both a compartmental unloader and a lateral heel wedge have been shown to be effective as short-term pain relief methods (Brouwer et al, 2005). This can play a role in at least delaying the need for a Total Knee Replacement (Wilson et al, 2011). Additionally, we must consider what mechanical issues may be predisposing a patient to genu varum alignment. It is well documented that abnormal strength of the hip muscles can alter knee mechanics. Strengthening the hip external rotators and hip extensors, for example, is a key component in the rehabilitation of patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Zeni and Synder-Mackler discuss the importance of strengthening the contralateral limb following a total knee replacement. They also report that decreasing body mass may have an impact on forces across the knee following replacement. Other authors discuss quadriceps strength as an important measurement to consider when viewing the success of a total knee replacement. There are examples across the literature that stress the importance of a lower limb strengthening and endurance program to decrease stresses at the knee to help prolong total joint replacements. While there may not be direct evidence linking hip strengthening programs to decreasing genu varum alignment, hip strength is definitely a measure to address when working with this population. Again, unfortunately, we were unable to find much evidence on exercise as a treatment for genu varum. What about you, what has your research and experience shown in addressing the condition? References:

Brouwer RW, Jakma TS, Verhagen AP, Verhaar JA, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. (2005). Braces and orthoses for treating osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. ;(1):CD004020. Web. 28 Jan 2013. Goutallier D, Hernigou P, Medevielle D, Debeyre J. (1986). Outcome at more than 10 years of 93 tibial osteotomies for internal arthritis in genu varum (or the predominant influence of the frontal angular correction. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot.;72(2):101-13. Web. 28 Jan 2013. Park YE, Song SH, Kwon HN, Refai MA, Park KW, Song HR. (2012). Gradual correction of idiopathic genu varum deformity using the Ilizarov technique. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. Web. 28 Jan 2013. Wilson B, Rankin H, Barnes CL. (2011). Long-term results of an unloader brace in patients with unicompartmental knee osteoarthritis. Orthopedics. ;34(8):e334-7. Web. 28 Jan 2013. Zeni J, Synder-Mackler L. (2010). Early post-operative measures predict 1- and 2- year outcomes after unilateral total knee arthroplasty: importance of contralateral limb strength. Journal of the American Physical Therapy Association.; 90(1): 43-54. Web. 29 Jan 2013.

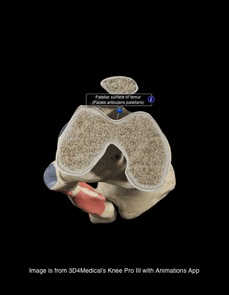

5 Comments

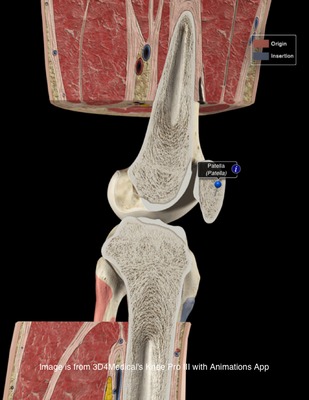

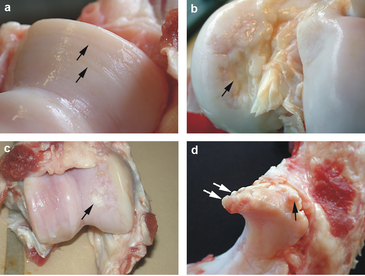

"Use of a Squatting Movement as a Clinical Marker of Function After Total Knee Arthroplasty"1/10/2013  With skyrocketing health care costs, insurance agencies are constantly looking for ways to reduce reimbursement. This includes decreasing payments to organizations that have poor outcomes. As most PTs are looking to stay in business, it is important that we have valid and reliable outcome measures in order to receive appropriate reimbursement. This study looked at the effectiveness of analyzing the symmetry of a squat as a clinical marker of function after Total Knee Arthroplasty. As many functional activities involve a squat-like maneuver, the squat may prove to be a valid measure for functional ability. The authors compared body weight % on each side in standing, 30 degree squats, and 60 degree squats. For anyone who has seen a knee replacement surgery, it's easy to understand why individuals place the majority of their weight on the uninvolved limb following surgery. The compensations caused by the asymmetries place the uninvolved limb and joints around the involved knee at risk for additional injuries due to their increased load. The study found that the 60 degree squat asymmetries was correlated with individuals who had moderate difficulty with functional activities, while standing asymmetries were not. Symmetry was found to be improved upon further rehabilitation. The squat may be a useful outcome measure when treating patients following total knee replacements. Upon further research, this may be a common tool used in the clinic for assessing patient progression.  With the success prehab has had with patients undergoing ACL reconstruction, there has been an increase in interest for prehab with total knee replacements as well. Quad strength has long been linked to functional outcomes following surgery. Given the strength deficits noted after surgery, it's possible improving strength prior to surgery may have an impact on patient outcomes. This RCT contained a placebo group and a lower body strengthening group. The placebo group performed non-specific upper body exercises, while the lower body group performed 10 minutes of warm-up and a set of exercises. The exercises included: standing calf raise, seated leg press, leg curl, and knee extension. Following prehab, increases in quadriceps strength, walking speed, and mental health were noted prior to surgery (improvements were noted in the control group as well). However, after surgery there was no difference between the control group and experimental group in these categories. Some potential limitations were a low sample size of 22 participants and a focus on open-kinetic chain exercises. It would be interesting to see the effects closed-kinetic chain exercises would have. While further research in this area is definitely still needed, it may be that prehab is not as pertinent for patients receiving a total knee replacement as compared to those preparing for ACL reconstruction. Reference: McKay C, Prapavessis H, & Doherty T. (2012). The Effect of a Prehabilitation Exercise Program on Quadriceps Strength for Patients Undergoing Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. PM&R: The Journal of Injury, Function and Rehabilitation, 4(9), 647-656.  No matter where you do your rotations or practice physical therapy, you are bound to work with both people who target the VMO with their interventions and people who think it's impossible to do so. Following trauma, knee surgery, or patellofemoral pain syndrome, many practitioners claim selective atrophy and weakness of the VMO relative to the rest of the quadriceps. This becomes a focus of several interventions in the patient's care plan. Due to the controversial state of this case, we thought we would do a review on the isolation of the vastus medialis muscle. CONTINUE READING  There is a lot of confusion in the health care community about chondromalacia patella (CP). Many practitioners use it simply to identify individuals with anterior knee pain. This can lead to difficulty when researching the evidence regarding CP. Due to the relationship between CP and patellofemoral pain syndrome, many of the treatment methods are similar. This will be explained in further detail later on. Clinical Presentation: Patients with chondromalacia of the patella will often complain of pain with knee flexion and extension, difficulty climbing stairs, crepitus, and pain that increases progressively. The pathology tends to affect women more than men, has an insidious onset, and is usually bilateral. Often there is no specific traumatic injury. These patient's will frequently demonstrate an increased Q-angle and contracture of the lateral retinaculum of the patella. Additionally, patients may present with patella alta (creating increased wear in the lateral part of the patella), increased valgus angle, and femoral condyle hypoplasia, which predispose the individual to changes in the cartilage (Harman, 2003). The patella functions as a mechanical lever for the quadriceps muscle. As knee flexion increases, the compressive force of the patellofemoral joint increases as well, further stressing the joint. Localized pressure at the middle and inferior facets of the patella results when the knee is hyperextended or the knee is flexed beyond 90 degrees. The altered articular cartilage and changes in synovial fluid can create a chronic inflammatory state within the knee joint, which can accelerate the degenerative processes occurring in the knee. One study looked at the pathological process in the development of CP, "The initial lesion was at the matrix of cartilage, the collagen network was disrupted, then proteoglycan was lost. The microenvironment of chondrocytes was changed with degradation of matrix. So the chondrocytes became degenerative and necrosis from superficial to deep layer, then feed back the matrix again. Finally, the total cartilage layer might disappear, and the bone under cartilage might proliferate. At late stage, the cartilage was completely destroyed and had no self-restorative ability" (Ye et. al, 2001). CP can have both acute and chronic causes. Acute chondromalacia is associated with instability, direct trauma and fracture, while chronic chondromalacia is related to subluxation, increased Q angle, quadriceps imbalance, posttraumatic mal-alignment, excessive lateral pressure syndrome, late effects of direct trauma or pressure and PCL injuries (Harman, 2003). Repetitive microtrauma to the patellofemoral joint, external trauma, or sudden increases in leg exercise load/frequency can contribute to chondromalacia (McMullen et. al 1990). More recently, practitioners are looking at core muscle weakness as a potential cause of chrondromalacia in the knee. Decreased hip abductor and hip extensor strength has been shown to create poor pelvic support, decreased femoral internal rotation, and poor valgus positioning. The strength deficits can also create gait abnormalities such as in-toeing and a trendelenburg pattern.  Diagnosis: As stated earlier, chondromalacia is sometimes used by clinicians to identify individuals with anterior knee pain. To develop a true diagnosis of chondromalacia, visual observation of the articular changes on the cartilage must be performed (Brotzman & Wilk, 2003). Dehaven et. al went so far as to say that patients are diagnosed with patellofemoral pain syndrome until visual observation of cartilage degradation occurred. At that point, the diagnosis would be changed to chondromalacia. The change in articular cartilage that occur is "arthritis in it's truest description" (Chevestick 2012). Because the articular cartilage is aneural, the patient's pain reports are always secondary from capsular, synovial or subchondral bone irritation (Gomoll 2006). One study reported that clinical examination for chondromalacia patella is relatively unreliable, which may present an issue for physical therapists. The most common feature is tenderness on palpation of the medial undersurface of the patella. Other signs that are reported are patellar crepitus, a positive apprehension test and effusion and pain on compressing the patella onto the distal femur (Macmull et. al, 2012). It should be noted that none of these signs are highly specific for chonrdomalacia. In fact, there is no correlation at all with the severity are amount of symptoms compared to staging of chondromalacia; therefore symptomatic severity should not be used when determining the need for an arthroscopy (Pihlajamäki HK et. al, 2010). One test that some practitioners choose to use is the Clarke Sign. Doberstein et. al reviewed the validity of the Clarke Sign in identifying individuals with chondromalacia. The test involves the examiner placing his/her 1st webspace of the hand against the superior pole of the patella. The patient is then asked to isometrically contract the quads (the examiner is blocking the patella from moving superiorly at this point). The test is considered positive if the patient is unable to maintain the contraction for >2 seconds due to pain. Unfortunately, this test was found to have low diagnostic accuracy: sensitivity (.391) and specificity (.675). On average the articular hyaline cartilage behind the patella is 3 mm thick, which often gives the appearance of a space when visualized on a radiograph. As the collagen becomes degraded, there is a decrease in sulfated mucopolysaccharides within the ground substance, which can alter the collagen matrix. X-rays can display decreased joint space in individuals with degradation, along with tracking issues of the patellofemoral joint; however, x-rays are basically only able to aid in diagnosis of late stage CP. Standard MRIs are not useful with early stages of chondromalacia as well. In fact, all imaging techniques have low sensitivity for early degeneration, but a MRA is the most sensitive with early stages. Essentially all imaging techniques are able to detect changes in the later stages (Harman 2003). Another study looked at the diagnostic accuracy of 1.0-T MRI for detecting chondromalacia: sensitivity (.60), specificity (.84), PPV (.75), and NPV (.72); however, the authors found sensitivity values .26-1.00 and specificity values .50-.94 when looking at other studies (Pihlajamäki HK et. al 2010). This means there is a lack of consensus on the various methods of MRI techniques and their diagnostic accuracies for detecting chondromalacia.

Conservative Treatment: Patients with chondromalacia of the patella are first directed to physical therapy for conservative management. A primary intervention of conservative treatment is a strict quadriceps strengthening program to help centralize the compressive forces during quadriceps contraction. Gomoll et. al believes placing the patients on a stretching program, emphasizing the quadriceps, hamstrings, and Iliotibial band is an important component. Additionally, they emphasized isometric and short arc closed-chain concentric and eccentric exercises. Isometrics are thought to avoid unusual loading on the defected cartilage. It is important to identify the contributing factors and address them when treating patients with chondromalacia. The McConnell taping technique, which is often used with patellofemoral pain, is a good intervention to help promote proper patellar tracking. The primary goal is to "restore soft tissue balance in the patellofemoral joint (Gomoll 2006)." Patients with knee pain often present with poor strength in the hip and pelvic musculature. Therefore, these muscles should be a focus in treatment, especially the hip lateral rotators and extensors. These muscles can decrease the valgus stress places on the patellofemoral joint, resulting in less stress on the articular surface of the patella. Check out our previous post on treating patellofemoral pain syndrome for exercises that specifically address these impairments! One study looked at static and isokinetic exercises in treating chondromalacia. With static exercises (knee extended), compressive forces of the patellofemoral joint are minimized, because the patella is contacting the supratrochlear fat pad. Therefore, the quadriceps would could be strengthened, while minimizing stress on the knee. With high-speed isokinetic strengthening, the theory is that the surfaces of the joint are moving so fast that "hydroplaning" would occur. Stress would be minimized because the surfaces are moving too quickly. The study found that both static and isokinetic exercises improved several functional outcomes (walking, running, jumping/twisting, overall activity, and stairclimbing); however, no change in pain occurred (McMullen et. al 1990). Yildiz et. al performed a study on the effects of an isokinetic protocol for individuals with chondromalacia as well. The participants experienced improved functional ability, strength and pain following the protocol. Isokinetic exercise may be something to consider in rehabbing your patient. Chondromalacia is a frequent (and likely incorrect) diagnosis in athletes. In one particular study, the effect of a protocol that had 4 phases was reviewed: symptomatic control, progressive resistance exercise program of isometric quadriceps and isotonic hamstring exercises, a graduated running program, and a maintenance program. To decrease symptoms, the patients would stop activities that aggravate symptoms and take salicylates regularly. The progressive resistance exercises included isometric quad exercises and isotonic hamstring exercises. These were performed 3 sets of 10, 5-6 days/wk. The running program was begun once the symptoms were controlled and the patient could lift 30 lb with quads. Initially, jogging was all that was permitted. As the patient progressed in quadriceps weight levels, so did the running style increase: 30 lb - jogging, 35-40 lb - half speed, 40-50 lb - three quarter speed, 60 lb - full speed/cutting. The final phase involves unrestricted activity, continued use of the progressive resistance exercise program at least 2-3 days/wk, and other adjunctive measures like knee pads, patellar braces, and shoe orthotics (Dehaven et. al, 1979). The program was found to be successful in 82% of the patients. There is often debate about the choice between open and closed-chain exercises for treating knee disorders. One study looked at the benefits of each method for chondromalacia; however, the authors identified chondromalacia as "anterior knee pain," so the participants did not truly have chondromalacia (big surprise). The CKC group performed partial squats, whle the OCK group performed SLR. Each group performed their exercises 20x, twice every day for 3 weeks. Every 2 days, an additional 5 reps would be performed. The results found both groups improved upon pain, but the CKC group had significantly greater improvements in thigh circumference, Q-angle, crepitus, and muscle force (Bakhtiary & Fatemi, 2008). Some potential adjuncts to exercise may include utilization of NSAIDs, injections, and warming needling. If the chondromalacia is not complex, NSAID's have been shown to be beneficial. The more degradation that has occurred in the cartilage, the more invasive treatment becomes. Typically patients with more complex chondromalacia are given a viscosupplementation injection to help increase viscosity and lubrication within the knee joint. Dry needling is becoming a more prominent treatment option for many pain disorders. The theory is that with application of needles, endorphins in the CSF and serotonin in the peripheral blood have increased levels, leading to an analgesic effect. Ling et. al found that warming needling combined with rehabilitation training was more effective in reducing long-term pain than rehabilitation training plus NSAIDs. Surgical Management: When conservative measures fail, surgery is typically the next course of action. The surgical procedure is dependent upon the stage of chondral disease with which the client presents. If the patient has patellar tilt (Outerbridge Level I or II*) The goal of this surgical operation is to restore proper tracking of the patella. Another common surgical procedure is a tibial tubercle osteotomy. The osteotomy attempts to normalize the tibial tubercle to trochlear groove distance. By achieving this, normal congruency is achieved at the patellofemoral joint and less contact stress is induced. One study looked at the effects of arthroscopic debridement for chondromalacia grades III & IV (Outerbridge levels). The treatment involved shaving the remaining cartilage until bleeding bone was reached. Additionally, all the joints were lavaged, and intra-articular debris was removed; this included partial meniscectomies. Following surgery, patients would assume partial weight-bearing on crutches for 5 days before being progressed to full weightbearing. The authors were unable to provide any true indications for when arthroscopic debridement should be performed in grade III & IV chondromalacia, but they still believe it is indicated for certain populations to prolong additional surgery (van den Bekerom et. al, 2007). Given the lack of findings, the evidence is questionable. Other surgery techniques you may see include Bone Marrow Stimulation (Microfracture begins the healing process by making perforations in the subchondral bone), Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation, Osteochondral Grafting, and Patellofemoral Prosthetic Arthroplasty (for patients too young for a TKA). Macmull et. al looked at autologous chondrocyte implantation versus matrix-assisted chondrocyte implantation for chondromalacia. The study found that both methods improved patient symptoms and function, but matrix-assisted chondrocyte implantation was more effective (Macmull et. al, 2012). Again, the type of surgery is largely based off the degree of articular cartilage degradation and other biomechanical influences. Regardless of the surgical technique, patients will go through a strict physical rehabilitation process afterward. A potentially overused treatment for chondromalacia (and patellofemoral pain syndrome) is surgical release of the lateral retinacular fibers. In one study, patients with Q angle >20 degrees did not benefit by lateral release as much as patients with normal Q-angle. The theory is that lateral retinacular fiber release can decrease some of the lateral tracking forces of the patella. Additionally, severing the nerve endings in the internal retinaculum may explain some of the analgesic effects (Vaatainen et. al, 1994). Another study found lateral retinacular release to be as effective as lavage and may be appropriate for patients with patella decentration 5-10 mm and appropriate pain symptoms (Kruger et. al, 2002). Given the conflicting findings, lateral retinacular release should not be an initial course of action. *Outerbridge Classification is used to grade amount of articular cartilage arthritis. (Chevestick 2012) Grade 0: Normal Cartilage Grade 1: Cartilage with softening and swelling Grade 2: Partial Thickness defect with fissures on the surface that do not reach subchondral bone or exceed 1.5 cm in diameter Grade 3: Fissuring to the level of subchondral bone in an area with an area >1.5 cm in diameter Grade 4: Exposed subchondral bone. References:

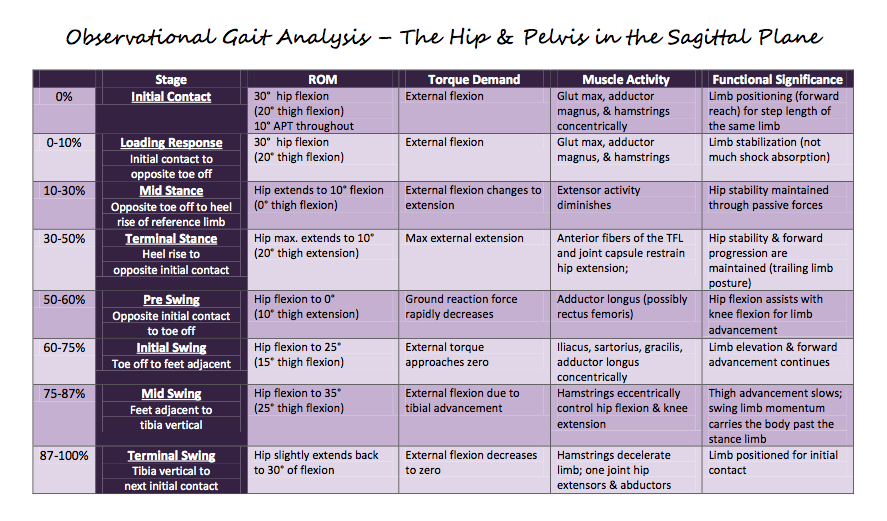

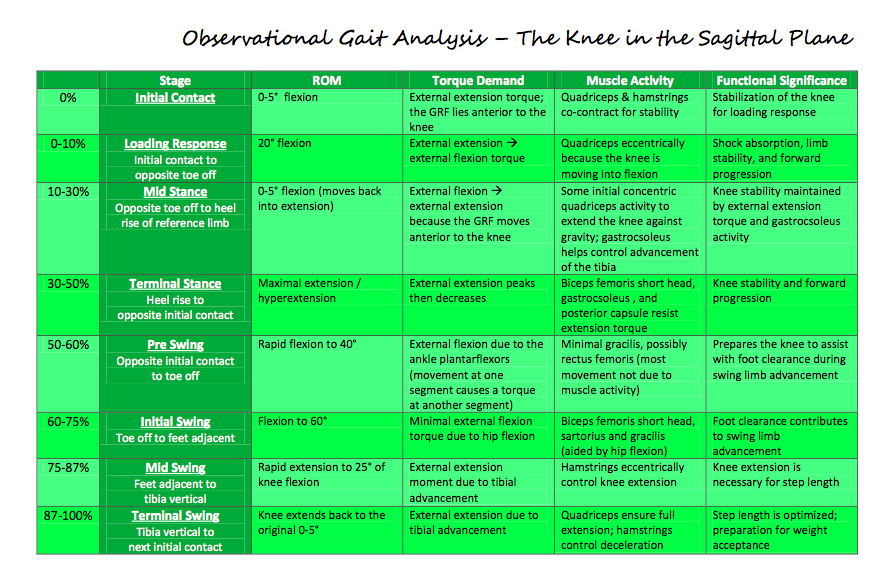

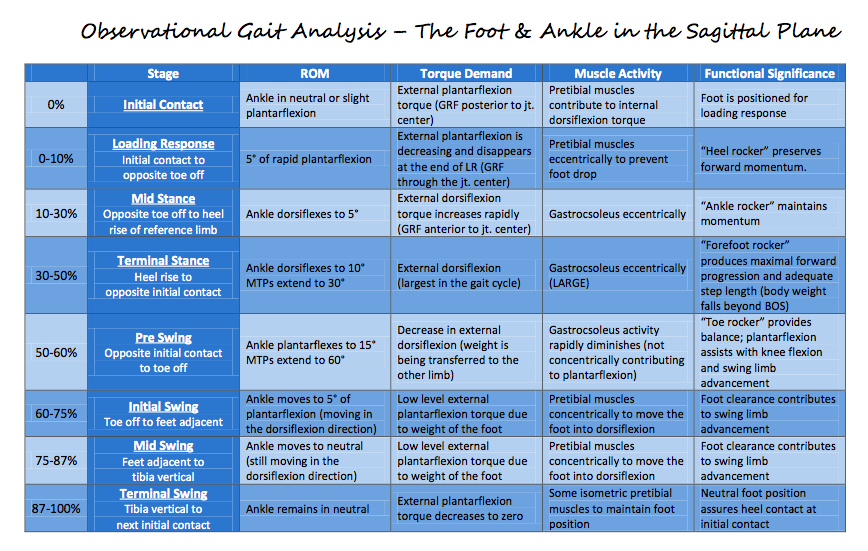

Bakhtiary AH, Fatemi E. "Open versus closed kinetic chain exercises for patellar chondromalacia." Br J Sports Med. 2008 Feb;42(2):99-102. Web. 9 Nov 2012. Brotzman, S., & Wilk, K. Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2003. 320. Print. Chevestick, A, et al. "Anterior knee pain: the pitfalls of plica and chondromalacia patellae." Advance Newsmagazines. 2.6 (2012). Web. 7 Nov. 2012. Dehaven K, Dolan W, & Mayer P. "Chondromalacia patellae in athletes: Clinical presentation and conservative management." Am J Sports Med. 1979 Jan-Feb;7(1):5-11. Web. 8 Nov 2012. Dehaven KE, Dolan WA, Mayer PJ. "Chondromalacia patellae and the painful knee." Am Fam Physician. 1980 Jan;21(1):117-24. Web. 9 Nov 2012. Doberstein ST, Romeyn RL, Reineke DM. "The diagnostic value of the Clarke sign in assessing chondromalacia patella." J Athl Train. 2008 Apr-Jun;43(2):190-6. Web. 9 Nov 2012. Gomoll, Adreas, et al. "Treatment of Chondral Defects in the patellofemoral joint." Journal of Knee Surgery. 19.4 (2006). Web. 7 Nov. 2012. Harman, Mustafa, et al. "MR Arthrography in chondromalacia patellae diagnosis on a low field open magnet system." Journal of Clinical Imaging. 27 (2003). Web. 8 Nov. 2012. Krüger T, Göbel F, Huschenbett A, Hein W. "Significance of lateral release in the therapy of patellar chondromalacia." Zentralbl Chir. 2002 Oct;127(10):900-4. Web. 9 Nov 2012. Ling Q, Min Z, Ji Z, Le-nv G, Da-wei C, Jun L, Jia-yi S, Ling W, Jin-yan Y, Le-ping H, & Yang B. "Chondromalacia Patellae Treated by Warming Needle and Rehabilitation Training." Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. June 2009; 29: 90-94. Web. 8 Nov. 2012. Macmull S, Jaiswal PK, Bentley G, Skinner JA, Carrington RW, Briggs TW. "The role of autologous chondrocyte implantation in the treatment of symptomatic chondromalacia patellae." Int Orthop. 2012 Jul;36(7):1371-7. Web. 9 Nov 2012. McMullen W, Roncarati A, Koval P. "Static and Isokinetic Treatments of Chondromalacia Patella: A Comparative Investigation." JOSPT. Dec 1990. 12:6: 256-265. Web. 8 Nov 2012. Murphy E, FitzGerald O, Saxne T, Bresnihan B. "Increased serum cartilage oligomeric matrix protein levels and decreased patellar bone mineral density in patients with chondromalacia patellae." Ann Rheum Dis. 2002 Nov;61(11):981-5. Web. 9 Nov 2012. Pihlajamäki HK, Kuikka PI, Leppänen VV, Kiuru MJ, Mattila VM. "Reliability of clinical findings and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of chondromalacia patellae." J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010 Apr;92(4):927-34. Web. 9 Nov 2012. Salehi I, Khazaeli S, Hatami P, Malekpour M. "Bone density in patients with chondromalacia patella." Rheumatol Int. 2010 Jun;30(8):1137-8. Web. 9 Nov 2012. Vaatainen U, Kiviranta I, Jaroma H, Airaksinen O. "Lateral Release in Chondromalacia Patellae Using Clinical, Radiologic, Electromygraphic, and Muscle Force Testing Evaluation." Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994 Oct;75(10):1127-31. Web. 8 Nov. 2012. van den Bekerom M, Patt T, Rutten S, Raven E, van de Vis H, & Albers G. "Arthroscopic Debridement for Grade III and IV Chondromalacia of the Knee in Patients Older Than 60 Years." J Knee Surg. 2007; 20: 271-276. Web. 8 Nov. 2012. Ye QB, Wu ZH, Wang YP, Lin J, Qiu GX. "Preliminary investigation on the pathogeny, diagnosis and treatment of chondromalacia patella." Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2001 Apr;23(2):181-3. Web. 9 Nov 2012. Yildiz Y, Aydin T, Sekir U, Cetin C, Ors F, Alp Kalyon T. "Relation between isokinetic muscle strength and functional capacity in recreational athletes with chondromalacia patellae." Br J Sports Med. 2003 Dec;37(6):475-9. Web. 9 Nov 2012. This is a a great video review by The Sports PhysioTherapist on Juvenile Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee. Check out his website for some great information! Because we all strive to be movement analysis specialists, a little gait mechanics review never hurts. Each graph breaks down the ROM requirements, muscle, torque demand, and functional significance as described by Rancho Los Amigos. All graphs courtesy of Saint Louis University student, class '12.

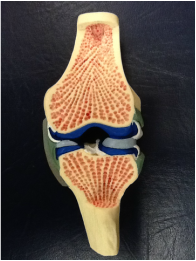

In each knee, there is a medial and lateral meniscus attached to the proximal tibia that accepts the femoral condyles. The shape and composition of the menisci serve to increase the surface area of contact at the tibiofemoral joint. On the medial side, the meniscus is oval-shaped and attaches to the capsule and medial collateral ligament. On the lateral side, the meniscus is more circular and attaches to the lateral capsule. The cusp-like form of the meniscus conforms to the convex shape of the appropriate femoral condyle. Due to the structural makeup of the meniscus, compression during weight-bearing activities is absorbed via circumferential tension (hoop stress) and allows the meniscus to deform peripherally. By increasing the surface area, there is a resultant decrease in stress on both the tibia and femur. Each meniscus is anchored to the intercondylar area at the anterior and posterior horns. The peripheral aspects of each meniscus adheres to the tibial plateau and capsule via coronary ligaments, and an anterior transverse ligament connects to two menisci. With the loose attachments of the meniscus to the knee, significant movement is permitted by each meniscus. According to Neumann, the quadriceps and semimembranosus muscles attach to both menisci, while the popliteus muscle attaches to the lateral meniscus only. These muscular attachments can aid in stabilizing the relatively loose menisci during knee motion, but also can put too much stress on the meniscus during recovery from surgery. The menisci are also important for guiding arthrokinematic motion, proprioception, lubricating the articular cartilage, and stabilizing the knee. The mechanism of injury can often be useful in diagnosing the pathology. In traumatic cases, the meniscus is often torn by twisting of the femur on a flexed knee and fixed tibia. Due to the proximity of the menisci to other structures of the knee (MCL, ACL, etc.), common mechanisms of injury, such as a valgus collapse, can injure the meniscus as well (remember the medial meniscus attaches to the MCL). Patients often complain of having "twisted" their knee, hearing a "pop," joint line pain that is increased during weight-bearing, and possibly having the joint lock in place. It is widely accepted that the medial meniscus is torn more frequently than the lateral, however, one of the studies we looked at stated that the opposite might be true. Meniscal tears are commonly associated with ACL injuries. During an ACL rupture as a result of a valgus collapse, it is the lateral meniscus that has been found to be torn more frequently due to the compression forces between the tibia and femur. The medial meniscus is found to be torn more frequently in the chronic ACL-deficient knees as a result of repetitive translation of the tibiofemoral joint. In the acute cases, we may or may not see joint effusion and a flexed-knee gait pattern. Patients may be unable to achieve full extension, due to a block caused by a meniscal tear. When the mechanism of injury is not clear, or in non-traumatic cases, we as clinicians have many options to assess the integrity of the menisci. The McMurray Test is used commonly when assessing the menisci, but due to its low diagnostic accuracy, should only be used when clustered with other tests (pain with flexion overpressure, pain with extension overpressure, joint line tenderness, and a hx of locking - check out the knee homepage for the criteria!). Another special test, the Thessaly Test, has very good diagnostic accuracy. As far as imaging goes, MRIs are commonly used with a contrast to identify meniscal tears, but do not always visualize well enough to be certain. Arthrograms are a cheaper option, but are not as sensitive and specific as an MRI. An arthroscopy can increase certainty with direct visualization. There are many factors that should come into consideration when addressing a meniscal injury in an individual. One of the most important ones is age. The standard meniscus has good blood supply to the peripheral 1/3, decent blood supply to the middle 1/3, and poor blood supply to the central 1/3. Obviously, the blood supply can translate into ability to regenerate. When we are younger (especially the skeletally immature), there is increased vascularity throughout the entire meniscus, which translates into an even higher potential for regeneration. With this knowledge, it is widely accepted that adolescents will have a surgical procedure for a meniscal repair. In a study on young athletes, meniscal repairs had good results for peripheral and central tears. The study used the "inside-out" technique that has shown significant success. Another factor that comes into play is whether or not an ACL reconstruction occurred at the same time. Many studies have shown that individuals who simultaneously had their ACL reconstructed and a meniscal repair had better results. The theory is that the hemarthrosis created by the ACL reconstruction aided in healing factors for the meniscus. Studies have also shown that the risk for retearing the meniscus is higher when located centrally, where there is poorer blood supply. Stability of the knee can play a role in the likelihood of retearing the meniscus as well. In an unstable knee, additional arthrokinematic motion can occur; thus, additional stress can be placed on the meniscus. A large contributing factor to potential for repair is the type of tear i.e. bucket-handle, longitudinal, radial, etc. The issue is that this cannot be identified without direct visualization. Tears like a bucket-handle often are partially removed instead of repaired, due to the destruction of the collagen tension lines. Another important note is that these factors can play a role in the pace of the rehab program. With characteristics that are shown to have increased healing rates, a more aggressive rehab protocol can be utilized. In the adult population, since repairs are less likely to be successful, a partial meniscectomy is often preferred over a total meniscectomy. In the past, total meniscectomies were performed frequently without concern; however, over time a link has been shown between those who had their entire meniscus removed and the development of osteoarthritis. As the understanding of the importance of the menisci increased, we learned how the menisci were responsible for decreasing the stress placed on the articular cartilage and bone. As a result of this finding, surgical procedures were adjusted to try and preserve the meniscus as much as possible, which led to thedevelopment of the partial meniscectomy. In those who choose to still pursue a complete meniscectomy, it has been shown that adherence to an exercise program can delay or reduce the risk of developing OA. One of the major correlations for developing OA is reduced thigh muscle strength. It is known that an exercise program can reduce this risk factor. In a partial meniscectomy, the tear is often removed and the remaining meniscus is smoothed out, so that any fraying cannot lead to another tear. In elderly individuals, where degeneration injuries are more common, studies have shown an initial bout of conservative therapy (physical therapy) can often delay or sometimes eliminate the need for a partial meniscectomy, however, this is a debatable topic where further research is needed. One study in particular found that in an exercise group vs. an arthroscopic partial meniscectomy + exercise group, no difference was found in results. It should be noted that the participants only had non-traumatic meniscal injuries. In the athletic population, some athletes have the option of returning to sport to finish the season, while having the meniscal tear remain. This could delay surgery until the season is finished. However, if the athlete was unable to withstand the symptoms, surgery could be utilized. The article did not discuss if conservative therapy was used during the season to try and alleviate symptoms. An important consideration is the time period between injury occurrence and surgical procedure. An article found that better results were achieved if the repair occurred within 8 weeks of injury for traumatic meniscal injuries. The longer the tear was present, the more likely OA developed. As far as rehabilitation of individuals following meniscal repairs goes, PTs are often found following the protocol of the surgeon in a step-by-step process. As expected, there is a wide variety of both conservative and accelerated programs that can vary from 10 weeks to 7 months for return to sports. Research is underway that will hopefully aid in determinig the appropriate speed of a rehab program. A study on animal meniscal repairs found that 80% of the tensile strength was achieved after 12 weeks. Variable factors include whether or not an immobilization period is used (and how long that phase is), weight-bearing restrictions, ROM limitations based on time from surgery, concomitant surgeries such as ACL reconstruction can influence the rehab protocol, and of course activities that stress the meniscal repair more forcefully. One study showed that prolonged immobilization is linked to decreased collagen content. It is interesting to note that it is not necessarily the weight-bearing element that stresses the meniscus, but the combination of weight-bearing with gliding of the tibio-femoral joint and of course rotation of the knee. As physical therapists we work on treating the patients' impairments, such as flexibility, strength deficits (especially the quads), and tasks that involve a high level of balance and neuromuscular coordination. Sport-specific training is included, when appropriate. An additional method of treatment that should be considered is the use of aquatic therapy. Aquatic therapy has been used in accelerated ACL rehab programs with success and could find benefit with meniscal repairs as well. The pool environment addresses the concern of weight-bearing and stress put on the repair. More advanced exercises can potentially be implemented earlier in the pool due to that decrease in stress. Something to consider, however, is the resistance put on hamstrings, due to their attachment to the menisci. Be sure to know any limitations the surgeon has on hamstring activity before using the pool. Some more experimental methods are out there to try and facilitate meniscal repair. The fibrin clot is a procedure where a fibrin clot matrix is injected into the meniscal tear to promote normal healing processes. While the meniscus was repaired, it was unable to resist the stresses that a normal, healthy meniscus can withstand, so the additional healing factors can potentially improve the process. Another procedure being explored is vascular access channels. As the name might explain, tunnels are created to connect the vascular areas of the meniscus to the avascular areas that are damaged in order to try and redirect the healing nutrients to the injured site. This method has had positive results in the initial studies and could potentially be useful for particular cases! Synovial abrasion is a process that involves surgical irritation of the synovial lining of the knee. The purpose is to have the healing cells from the synovium aid in healing the damaged meniscus. This technique is used frequently during surgeries. Many researchers are also trying to develop working meniscal transplants. Right now there are various methods of transplants for a meniscus: fresh allografts, deep-frozen allografts, cryopreserved allografts, and freeze-dried allografts. Of the four listed there, the fresh allografts and cryopreserved allografts provided the best potential results, but the long-term outcomes are still unknown. On a related topic, researchers are also looking at constructing collagen scaffolds that can provide the characteristics necessary for fibrochondrocyte ingrowth that could lead to meniscal regeneration. Something to look out for in the future! A recent study utilized a treatment known as AposTherapy for individuals with degenerative meniscal injuries and potential development of OA. The researchers analyzed the gait of the participants. Each individual was then given shoes that had an element placed on the hindfoot and an element placed on the forefoot (customized following the results of the gait analysis) that were designed to alter the gait of the individual. Participants gradually built up tolerance wearing the devices each day. After 12 months, significant changes were noted in the participants' gait patterns, especially increased gait speed, SLS, and step length. When further research is done, this could be an interesting treatment option to delay the need for surgical intervention and could be useful for treating those at risk for developing OA as well. References: Brindle T, Nyland J, Johnson DL. "The meniscus: review of basic principles with application to surgery and rehabilitation." J Athl Train. 2001 Apr;36(2):160-9. Web. 09/22/2012. Elbaz A, Beer Y, Rath E, Morag G, Segal G, Debbi EM, Wasser D, Mor A, Debi R. "A unique foot-worn device for patients with degenerative meniscal tear." Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012 May 4. Web. 09/22/2012. Englund M, Roemer FW, Hayashi D, Crema MD, Guermazi A. "Meniscus pathology, osteoarthritis and the treatment controversy." Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012 May 22;8(7):412-9. Web. 09/22/2012. Ericsson YB, Dahlberg LE, Roos EM. "Effects of functional exercise training on performance and muscle strength after meniscectomy: a randomized trial." Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009 Apr;19(2):156-65. Web. 09/22/2012. Giuliani JR, Burns TC, Svoboda SJ, Cameron KL, Owens BD. "Treatment of meniscal injuries in young athletes." J Knee Surg. 2011 Jun;24(2):93-100. Web. 09/22/2012. Greis PE, Holmstrom MC, Bardana DD, Burks RT. "Meniscal injury: II. Management." J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002 May-Jun;10(3):177-87. Web. 09/23/2012. Herrlin S, Hållander M, Wange P, Weidenhielm L, Werner S. "Arthroscopic or conservative treatment of degenerative medial meniscal tears: a prospective randomised trial." Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007 Apr;15(4):393-401. Web. 09/22/2012. Kraus T, Heidari N, Švehlík M, Schneider F, Sperl M, Linhart W. "Outcome of repaired unstable meniscal tears in children and adolescents." Acta Orthop. 2012 Jun;83(3):261-6. Web. 09/22/2012. McCarty EC, Marx RG, Wickiewicz TL. "Meniscal tears in the athlete. Operative and nonoperative management." Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2000 Nov;11(4):867-80. Web. 09/22/2012. Neumann, Donald. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System: Foundations for Rehabilitation. 2nd edition. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier, 2010. 526-528. Print. Pyne SW. "Current progress in meniscal repair and postoperative rehabilitation." Curr Sports Med Rep. 2002 Oct;1(5):265-71. Web. 09/22/2012. Vanderhave KL, Moravek JE, Sekiya JK, Wojtys EM. "Meniscus tears in the young athlete: results of arthroscopic repair." J Pediatr Orthop. 2011 Jul-Aug;31(5):496-500. Web. 09/22/2012.

There have been many suggestions on how to treat patients with this diagnosis. One common method, focuses on decreasing the effect of the valgus force at the knee by strengthening the hip external rotators and extensors. By decreasing the valgus forces, there is theoretically less compression on the lateral side of the patellofemoral joint.

There have also been studies on strengthening the quadriceps muscles with reported success. In the study, both closed-chain and open-chain exercises were used with improvement in function and pain. Some alternate methods that can be included in treating PFPS are taping of the patellofemoral joint and utilizing orthotics. While there has not been much evidence in using orthotics, if the patient is reporting a decrease in pain with use, it would not hurt for them to keep using the device. Taping, on the other hand, has shown to have success in improving pain and function when combined with exercise. The study looked at here utilized a program with 2 initial weeks of taping followed by exercise that had successful long-term outcomes. A final study we looked at was exercise vs. exercise and knee arthroscopy. Both immediate and 5-year follow-up reported improvements in pain and function; however, there was no significant difference between the two groups, suggesting that surgery may not be necessary for all individuals. From reviewing these articles, we like to try and take a conservative approach initially with patients of PFPS by including taping, exercises that strengthen the quads and hip external rotators/extensors, and possibly orthotics. Of course, consider using additional exercises and stretches with these patients, but surgery may not be the option for everyone. Check out the articles to decide for yourselves! References: Bolgla LA, Boling MC. "An update for the conservative management of patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic review of the literature from 2000-2010." Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2011 Jun;6(2):112-25. Web. 09/02/2012. Kettunen JA, Harilainen A, Sandelin J, Schlenzka D, Hietaniemi K, Seitsalo S, Malmivaara A, Kujala UM. "Knee arthroscopy and exercise versus exercise only for chronic patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized control trial." Br J Sports Med. 2012 Mar;46(4):243-6. Epub 2011 Feb 25. Web. 09/02/2012. Khayambashi K, Mohammadkhani Z, Ghaznavi K, Lyle MA, Powers CM. "The effect of isolated hip abductor and external rotator muscle strengthening on pain, health status, and hip strength in females with patellofemoral pain: a randomized control trial." J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012 Jan;42(1):22-9. Epub 2011 Oct 25. Web. 09/02/2012. Paoloni M, Fratocchi G, Mangone M, Murgia M, Santilli V, Cacchio A. "Long term efficacy of a short period of taping followed by an exercise program in a cohort of patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome." Clin Rheumatol. 2012 Mar;31(3):535-9. Epub 2011 Nov 3. Web. 09/02/2012. Swart NM, van Linschoten R, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, van Middelkoop M. "The additional effect of orthotic devices on exercise therapy for patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic review." Br J Sports Med. 2012 Jun;46(8):570-7. Epub 2011 Mar 14. Web. 09/02/2012. |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed