- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

Expected ECG Findings

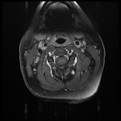

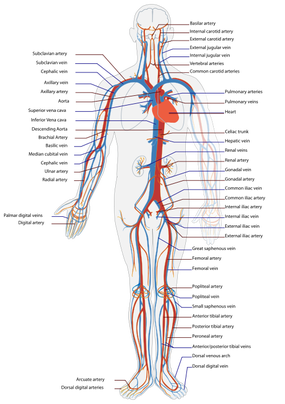

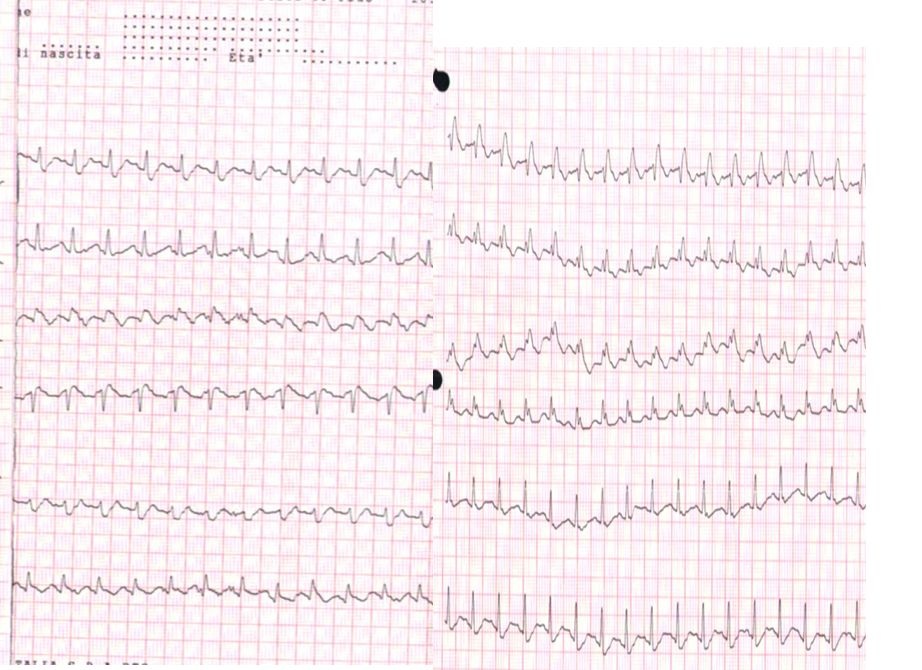

The easiest way to explain the heart rhythm is to refer back to an electrocardiogram (ECG - as depicted below). For review, we will go over the basics of an ECG first: -P Wave: depolarization of atria (starting at the SA node, then spreading out to the atria) -PR Interval: time it takes for the electrical pulse to get from the SA node to the AV node) -QRS Complex: depolarization of ventricles (starting at the AV node; re-polarization of atria hidden here) -T Wave: re-polarization of ventricles This patient in particular, as you recall, had 3 pulses followed by a pause. This likely signifies a Second Degree AV Block: Mobitz Type I (Wenckebach). This would be depicted at a slowly increasing PR interval, before a lack of QRS complex occurs. The cycle then restarts. Basically this means the signal from the SA node to the AV node slows until it doesn't make it through to initiate ventricular contraction, before the next SA node initiates again to restart the cycle. If you've ever struggled with interpretting ECG's, I recommend reading this book by Dale Dubin. It provides a step-by-step understanding and asssessment of ECG's along with the associated pathologies, at an MD level. It is an excellent source for reviewing for a CardioPulm course or preparing for the Cardiovascular section of the boards! -Chris

2 Comments

Pain science is becoming a more important aspect of physical therapy training. Many schools are not dedicating enough time to understanding how and why pain operates and persists. Fortunately, there is a wealth of resources on the internet to help supplement what is being taught in physical therapy education. On the TSPT blog, we have discussed this topic several times. (Here and Here). Recently, I stumbled upon this video produced by Brett Peterson, MPT, OCS, FiT on the PT Coop website. His video outlines: a) A brief history of the past and current pain theories b) Psychological components of pain c) Perception and the relationship to pain d) Treatment options for physical therapists

As this was my student's first initial evaluation on this clinical (and first ortho one in months), I can understand being a bit nervous and focusing in on the knee. The patient had complaints of vague thigh pain and the need to do a wider examination became even more apparent. I encouraged the student to perform a lumbar spine examination and slump test. Both back and the thigh pain were recreated, suggesting lumbar involvement to the current impairment level. While I typically prefer using the SFMA for evaluations, I typically do not do so with post-surgical patients. That being said, I do still have a system that I run through in assessing surgical patients. For example, in any lower extremity or back surgery, I assess lumbar/hip/knee/ankle mobility and strength, SIJ pain provocation tests, hip scour/FABER/POSH tests, neural tensioning, and segmental mobility. Based on the surgery, sometimes a modification is needed, but I still like to assess each area for potential contribution to the patient's pain and limitations. The benefit of having some form of a systematic examination results in lowering the chances of missing true causes and sources of the pain. Both are listed because the source of pain is not always the reason pain occurred in the first place.

While this was a difficult patient to evaluate, I am happy that my student was able to experience it so early in the rotation. It served a perfect example as to why we need to be thorough with our examinations, no matter the referral. Since then, she has done an outstanding job of taking a more global approach with each assessment. Physical therapists often go years before recognizing the need for development of a system. While this post might appear somewhat redundant to the previous posts we have had on the topic, the value of becoming more efficient clinicians can not be over-emphasized. -Chris  I have had a few "higher level" patients in the past few weeks and one consistent trend I found in my practice is that I have been progressing them too quickly. I am not exactly sure why this in the case. Both groups of people present with the same impairments so why would I treat them differently? My assumptions are that I do not want them to become bored with a basic HEP or maybe because they are starting at a higher level they should require higher level exercises. Both of these are fallacies. Despite starting from a higher functional baseline the higher level patients presented with similar impairments as the low level patient. A 3+/5 muscle grade is a 3+/5 no matter how you look at it. For example, with a low level patient, I gave the clamshell exercise to strengthen the posterior gluteus medius. For the higher level, I gave the clamshell exercise in a modified side plank position. Both exercises target similar muscle groups, but the higher level exercise is much more demanding across the entire system. I have given similar exercise prescriptions like this is the past and consistently found that the patient returns to the clinic performing the exercise improperly or having pain while performing it. Lessons Learned: 1. A weak muscle is a weak muscle regardless of what type of patient you find it on. 2. Start basic. In my example above, I added side planks to a clam exercise during the initial HEP. When prescribing this, I made sure the patient had adequate abdominal control, but it took away from the true target of my treatment. The primary impairment was gluteus medius weakness. I needed to start in the least aggressive position and isolate the glut medius. 3. Educate appropriately. My assumption is fairly true in that higher level patients get bored easily with low level exercises. This patient population is used to performing strenuous exercises. Generally, despite being in pain, they want to perform something hard. As a therapist, educating them on the importance of the low level exercises and discussing the exercise progression in future visits will allow for more patient buy-in to your treatment. Do not be afraid to start at the most basic level. You are the expert and you no why they need to start at that level. -Jim  I performed 3 evaluations yesterday morning. The first individual has been having cervical pain since a MVA in 1991, the second low back pain since her first child 7 years ago, and the last individual was having bilateral radicular symptoms for the past 6 months following a discharge from the military. All 3 can be defined as having chronic pain. Knowing their duration of symptoms alone, how does this change my plan of care? How does it change my prognosis? What sort of goals need to be set between the patient and I? When a patient presents to you with pain for >6 months, they often are having pain in multiple joints. This makes sense from both a biomechanical and cortical reorganizing perspective. Biomechanically, if an individual is having pain, they will often start to move more from other body regions to avoid pain. These abnormal movements cause repetitive microstrains and result in pain as well. Additionally, individuals with chronic pain will posture themselves in non-painful positions throughout the day. You will often see them in a guarded, fearful posture. Looking at chronic pain from the cortical level, many changes begin occurring in the cortex in the presence of pain. Cortical smudging occurs and other areas of the brain become activated in the presence of pain. Some of these other areas are those associated with cognitive functioning and emotion so you can imagine how the pain completely envelopes their life. As you can tell already, there is no magical solution to treating these patients. But good approaches include using graded exercises, addressing all barriers that will prevent them from succeeding, and creating realistic and specific goals to measure success. Graded exercise is essential because many of these people STOP exercising in the presence of pain. We see them completely deconditioned, making it difficult to distinguish between true tissue pain or simply the aches and soreness associated with starting a new exercise routine. Start small and start slow! For example, as part of their HEP, I gave one of these patients a home walking program (based off the results of their 6 minute walk test): Walk 4 minutes, 3x/day. Yes, it seems simple, but it is realistic! Barriers also need to be addressed. Typically if someone has been having pain for ~20 years, they have tried to seek care elsewhere but it has been unsuccessful. Why is it unsuccessful? Maybe the musculoskeletal pain is not the only factor. You need to determine if they have financial barriers, transportation issues, psychological issues, social barriers, and more (all of this is obtained during the subjective interview, but gathered much more throughout subsequent visits as you develop a relationship with the patient). Finally, realistic goals must be set. If someone believes they have 10/10 & have been having that pain for 7 years, completely eliminating their pain is not a realistic goal. You need to determine what the patient wants to achieve and set obtainable goals with a set time frame. As you can imagine, adherence and compliance with therapy is another huge problem. Throughout these treatments, education is KEY. Sometimes it may feel that we turn into psychologists. This is partly true, but I say we have a little more power than them. Our research shows that graded exercise is beneficial for individuals with chronic pain. We can spend 1 hour listening to and educating the patient while having them exercise. Early in the treatment you may be taking on a "general exercising and conditioning" approach. This is fine! Stick with it and you will likely find you are often successful. -Jim

2. Check Patient Compliance: This is a big one and a common culprit. It is our job to educate our patients on why it is essential that they are regularly performing their HEP. If you think how much time our patients spend working with us compared to being outside the clinic, any significant gains must be made (or maintained) independently. With regular performance of an HEP, we should expect to see a weak muscle get stronger, an adaptively shortened muscle lengthen, etc. If we are not seeing the expected improvements, it's time for another chat with the patient. Patients will often complain of not having time to do their HEP. It is here we must tell the patient that we cannot accomplish what we want to do in the clinic without the expected results from a regularly performed HEP. If they are too busy, maybe they need to reschedule their appointment once they have found time.

3. Refer Out: Physical therapy is sometimes used as a diagnostic tool for physicians. We are movement experts and often have a different perspective to offer when examining patients compared to medical doctors. This option actually has a couple different considerations. As you might have guessed, we all likely have impairments that would benefit from physical therapy. Whether or not these impairments are linked to the pathology is a separate issue. That explains why failure to respond to physical therapy after a month is a red flag. Another concern in this area is musculoskeletal pathology that sometimes benefits from skilled physical therapy. An example is meniscal tears. A study came out last year showing that conservative management of meniscal tears was just as successful as surgical outcomes. However, this does not mean that everyone will always respond to physical therapy. If after a few weeks the patient has not seen any significant improvements and is experiencing acute locking/catching in the joint, this patient may not be appropriate for conservative care. This applies to other pathologies as well.  Some of you may remember reading this post on Doctors of Physical Therapy Website about a year ago, but we believe its message is consistent. One of the biggest barriers to changing our profession is a lack of patient education and understanding of who we are and what we do. This post presents a simple, consistent message: " I am (a) ___________." -Musculoskeletal Expert, Movement Analysis Specialist, Direct Access, Cost Effective, etc. We must advocate for our profession from the Patient-Upward and not strictly Top-Down. We cannot expect to persuade the AMA or Insurance Companies to give us rights if we have little support from our consumer. Spread the Word!!!  This editorial was brought to me during my residency at Harris Health. It is written by Jason Silvernail on the website SomaSimple. As therapists we often deal with 2 types of pain: Chemical and Mechanical. Understanding the difference between the two is important because it allows you to explain to your patients "why" they are experiencing pain. Chemical Pain is associated with inflammation, and responds positively to anti-inflammatory medication and rest. Mechanical Pain is more complex! It is due to prolonged pressure or tension on nervous tissue. When you see a patient with mechanical pain, they may have questions regarding why their MRI did not show anything significant OR why their medications are not working. This is because Mechanical Pain is due to how the tissue feels, and not the way the tissue looks. There is no acute inflammation and no acute tissue damage. Mechanical pain is a chronic irritation. To fix mechanical pain, we need prescribe movements that relieve the tension that is being placed on the nervous system. This specific movement will gradually or immediately allow the patient to experience less pain. The patient needs to be regularly reversing the postures that are placing tension on their nervous system. This is where doing your Home Exercise Program regularly becomes so important. Sometimes it can be difficult to tell a patient to MOVE when they are in pain, but by educating them that the specific exercises you are prescribing are actually taking tension off the involved structures can be a great for compliance. The last point I will touch on is how many sets and reps should be prescribed for mechanical pain. As therapists, we know how many repetitions to prescribe for strength training, neuromuscular re-education, and power, but how many reps do you prescribe for pain? The answer is unique to each patient and will vary based on comorbidities, irritability level, etc... I would recommend starting with a high repetition, low load dosage. This will minimize the risk for compensations, decrease the risk of increasing symptoms, and hopefully get the patient performing them more frequently. Reference:

Silvernail, J. "Understanding Mechanical Pain." Somasimple.com. Web. 14 Dec. 2013.  Our roles as physical therapists is constantly changing & seems to differ extraordinarily depending on what type of patient population you see. Currently, I see A LOT of chronic pain. If someone presents with chronic pain, usually this means the traditional medical model of care will not suffice. In these situations, it is important to use the biopsychosocial model of care if I plan to be successful. Part of the biopsychosocial model is understanding what barriers a person has to therapy. By addressing these barriers, the therapist will best be able to address impairments in the scope of the patient's life. Also by looking at these barriers, you will be able to see if a patient is ready for physical therapy. "Ready" you may be asking yourself? One reality I quickly stumbled across while practicing at a community hospital is that certain people have so many life stresses that take priority before their musculoskeletal health. If a patient comes to see you with cLBP, but also has a history of depression, transportation issues, financial problems, family problems, and reports little to no exercise, strengthening the PGM may not be the first thing they need. I would recommend starting this patient on a general exercise program and a few basic exercises. Going back to barriers, one of the biggest barriers I face each day is patient adherence and compliance. I often struggle with how to address these issues. Which clients are appropriate for PT and which are unfortunately not ready to change? Check out this post by Chris Johnson. He poses some great questions that will put you and the patient on the same level regarding your goals and their expectations of physical therapy. They may save you some time down the road. -Jim  In a recent post, we discussed our experience learning the Selective Functional Movement Assessment (SFMA). A large component of the SFMA is utilizing Rolling Patterns. These patterns are used whenever mobility is cleared and the patient has a pure stability or motor control dysfunction (SMCD). As Gray Cook states in Movement, "Rolling patterns offer a low-load opportunity to review symmetry and motor control, and are even less taxing than quadruped movements." Since the movement is so basic, strength is not what you are assessing. With rolling, the focus is directed toward sequencing, timing, breathing, upper extremity vs. lower extremity disassociation, and of course motor control. Gray also states, "Rolling and quadruped movement patterns are unique observations of fundamental reflex stabilization." In the developmental sequence, rolling is one of the most basic motor patterns. The SFMA assesses 8 different rolling patterns which are a combination of Left vs. Right, Supine vs. Prone, and Upper Extremity vs. Lower Extremity Patterning. On our Multisegmental flexion post, we were asked a question regarding the difference between SFMA rolling and the PNF rolling patterns. From our understanding, the rationale behind both rolling assessments/interventions is the same. Both try to assess side to side symmetry and upper quarter vs. lower quarter symmetry. They both focus on the demands of timing and reflex stabilization. The difference (and not necessarily a difference, but rather treatment style) is how PNF elaborates further on ways to facilitate the incorrect pattern. Someone can definitely utilize different PNF facilitation and inhibition strategies to address rolling in the SFMA, but always allow the patient to self-select a method first before giving any external cues. Without the ability to perform this basic movement properly, how can a patient expect to perform higher level movements? |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed