- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

With the vast amount of locations that non-musculoskeletal conditions can present with pain in the thorax, one red flag that often stands out is pain in the middle of the back. A patient that presents with a case of simple neck or shoulder pain resulting from forward head posture may appear to have red flags with night pain of the mid thoracic spine. However, with further questioning you will often discover that the patient prefers to sleep with multiple pillows, reproducing the forward head posture and potentially disc irritation. A pain presentation that is fairly common that we should be aware of is Cloward Areas. Cervical disc irritation has the tendency to refer to the mid thoracic spine and the scapular border. Think about how lumbar disc irritation can essentially refer down to the knees (and sometimes below). The cervical spine has the same feature. With careful questioning of when the thoracic pain comes about, you may notice that it occurs with sustained positioning of forward head posture and disappears with correction, thus lowering the likelihood of non-musculoskeletal involvement. This article contains a good summary of the abstracts related to Cloward Areas. Some of the studies discuss the usefulness of various imaging methods in diagnosing symptomatic discs. This is interesting because it recognizes the difference between symptomatic and asymptomatic radiological findings - something many overlook. What we must remember however, is that we do not treat the pathology based on imaging. We treat the impairments.

1 Comment

The Selective Functional Movement Assessment (SFMA) is a systematic method that focuses on whole body movement patterns. You might be familiar with the Functional Movement Screen (FMS) created by the same group. The FMS is a screen that can be used by any fitness professional. The SFMA is a diagnostic system (that can only be performed by medical professionals) similar to that of McKenzie. At the core of the SFMA is the concept of regional interdependence, "seemingly unrelated impairments in a remote anatomical region may contribute to or be associated with the patient's primary complaint." The assessment is broken into 7 Top Tier tests and graded as Functional and Non-painful (FN), Functional Painful (FP), Dysfunctional Non-painful (DN), and Dysfunctional Painful (DP). If a Top Tier test does not pass the FN grade, then that specific movement must go to a breakout pattern to find the true cause of dysfunction. To simplify things, the "true cause of dysfunction" can either be viewed as a mobility (Tissue Extensibility Dysfunction (TED)/Joint Mobility Dysfunction (JMD)) OR a Stability/Motor Control Issue (SCMD). Below is an example of Chris performing the Multi-Semental Flexion Top Tier Test with demonstration of the appropriate breakout patterns following. In the Multi-Segmental Flexion Top-Tier test, have the patient bend forward to touch their toes. The person assessing the movement should be looking for a uniform spinal curve, the thoraco-lumbar junction ending up over the feet, a sacral angle >70 degrees, and the ability to touch the toes without excessive exertion. If the person passes all the listed criteria, they are considered FN! Otherwise they are graded as DN, DP, FP and the Multi-Segmental Flexion breakout needs to be performed. As you can see, Chris is unable to touch his toes, so he is immediately given a DN (the motion was pain-free). At this point, we know they have some type of dysfunction. Whether it is a posterior chain extensibility issue or motor control issue, we are not sure. Therefore we must continue with the assessment. The next video (below), demonstrates the Single Leg Forward Bend. This will give you a sense if the dysfunction is symmetrical or not & if a single leg movement produces pain. In order to "pass" this test, the same criteria as above need to be fulfilled. All this test really tells you is if there is an asymmetry or not. As you can see below, Chris' movement is still DN, so the breakout continues (it would continue even if he received a FN). At this point, we know Chris has a dysfunctional movement pattern in standing so we need to see if the movement changes when he is placed in NWB. This tells us if he simply has a postural control issue. The next test (seen below) is the Long Sitting Test. To pass this test, Chris needs to touch his toes, have a sacral angle of at least 80 degrees, and have a uniform spinal curve. You will see in the video that he cannot touch his toes and the sacral angle does not reach 80 degrees. He has no pain, so the movement is graded DN. Hypothetically at this point, if Chris were to have passed (FN), we could assume he has a SMCD due to an issue with postural control because he is able to perform the motion once the effects of spinal loading have been reduced. He would then proceed to the Rolling component. Since Chris is unable to complete the motion when postural control is decreased, we now break apart each component of the motion to determine where the fault lies. To first assess the lower extremity component, we move to the Active Straight Leg Raise (seen below). This motion assesses the motor control/stability to actively flex the lower extremity, provided there is sufficient range. A minimum of 70 degrees of hip flexion is required. Be sure to watch that the contralateral thigh stays down and the knee remains extended on both legs. As you can see, Chris does not reach 70 degrees, so he receives a grade of DN. If Chris were able to complete this motion, we would know that Chris has adequate tissue/joint mobility and motor control in his lower extremities. We would then move on to the Prone Rocking Test. With Chris failing to pass the Active Straight Leg Raise, we must now move onto the Passive Straight Leg Raise to determine if the tissue/capsular length even exists for the motion to complete. A passing score would require 80 degrees of hip flexion (with the same precautions in the active test). Chris again does not pass the test (DN). If he had passed this test, we would then proceed to Rolling. After determining that there was a TED or JMD limitation, we can now use the Supine Knee to Chest test to determine if it is a 1 joint or 2 joint limitation (it could potentially be both). As you can see with Chris, he has a 1 joint limitation for sure (he likely has a 2 joint deficit as well) - DN. This positive test may indicate capsular hypomobility, decreased length of the gluteus muscles, or decreased neural mobility (or a combination). This is a location for treatment with Chris. Going back to the Active Straight Leg Raise Test, had Chris passed it he would have proceeded to the Prone Rocking Test below. With the lower extremity component of the Multi-Segmental Flexion Top Tier Test ruled out, we now need to assess the other primary component: lumbar flexion. A passing test requires a uniform curve and the thighs pressing against the lower rib cage. With the lower extremity motion already cleared, we now know the restriction if located in the lumbar spine as a TED or JMD. With the video below, it appears Chris receives a DN, but remember he had limited hip flexion, which can cause a false positive here. As you can see, the sequencing is important! Assuming this test receives a FN, we once again proceed to Rolling. Had your patient had a DN score here, this would again be a location of treatment for JMD or TED. Finally we arrive at the rolling pattern. once we have shown that adequate joint/tissue mobility is present for the required pattern, we can assess motor control patterns with this breakout. Look for your patient's ability as to whether or not they can complete the flexion rolling patterns. The motions should be smooth with dissociation of each component (you should not see log-rolling). Limited mobility anywhere in the chain can cause pauses or difficulties completing the motion (i.e. decreased cervical rotation could easily inhibit normal rolling, especially since it is the starting point for UE flexion rolling. Rolling can be scored just as the other tests. FN requires pain-free smooth rolling with no difficulty, pauses, or inability to dissociate the components - any of these lead to DN. DP and FP follow the usual scoring roles as well. Hopefully this gives you an idea of what the SFMA offers as a method of doing examination. This doesn't mean you should exclude your strength tests, special tests, neuro screens or even ROM measurements for certain patient populations. In a way, this method is even more objective than a goniometer allows due to the system's utilization of actual landmarks for completion. A goniometer may still have a place where regular progress is required (i.e. surgical patients, adhesive capsulitis, etc.). Instead this system can help to gain a very detailed look at each patient and ensure that you don't miss anything significant. Your patients often will comment how thorough you are (making you look like an even better PT!). The rest of the SFMA has a similar process of going through joint-by-joint assessments of motion and stability for the rest of the body as well. If you are interested in this, you may want to take the SFMA course. Gray Cook's book Movement details the system as well; however, the system has actually been updated since the book was written and is much more thorough and appropriate now. This method of examination has helped us to better determine the best locations for treatment and other potential causes to dysfunction. If you have any questions, do not hesitate to ask!

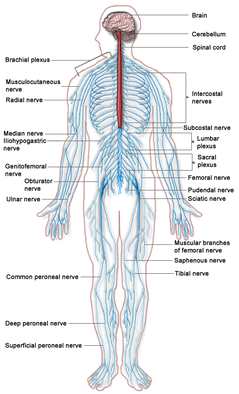

A similar technique often confused with nerve gliding is nerve sliding. Nerve sliding works by elongating the nerve bed at one joint, while simultaneously shortening it at another (Coppieters & Butler, 2008). The reasoning is that the nerve can move without increasing strain. It was found that nerve sliding creates the largest nerve excursions with the least amount of strain. Nerve gliding can potentially create even larger nerve excursions at proximal joints but it creates significant strain. Due to the chance for symptom provocation, nerve gliding should only be considered in non-acute and non-surgical conditions. It is here that nerve sliding is the preferred intervention. A recent study found that the sequencing of nerve tensioning/gliding at each joint was irrelevant when looking at net strain on the nerve (Boyd et al, 2013). However, it was also shown that variation in sequencing of joint movements altered where the nerve strain occurred first. This has potential clinical implications as we may be able to target specific locations if we know where the restrictions lie. The real-world applicability is unknown at this point as there have not been any studies performed in this area. When comparing education to education + neural tissue management (both nerve sliding/gliding were used with cervical manual therapy), it was found that the intervention group had superior results compared to the control with no significant increased risk of exacerbations (Nee et al, 2012). Not only is it important to note the benefit of these nerve gliding/sliding exercises, but it brings up the point that we should also be looking at the spine. Other than some form of direct trauma, another source of nerve irritation can come from poor spinal mechanics that lead to neural irritation. Treating just the nerve may mean treating just the symptoms in some cases. It is essential to look at the spinal and restore normal mechanics if any abnormalities are found, especially because a manipulation may immediately show symptom relief as well. There are two additional treatment techniques we wanted to mention. A case study we looked at utilized Active-Release Therapy (ART) for saphenous nerve entrapment (Settergren, 2012). In general, ART involves a technique where the clinician applies a force to the restricted area while the patient actively moves to "release" the adhesion. The technique often causes significant pain during the maneuver but is followed by increased mobility and decreased pain. This method may not be as useful to most clinicians as it involves extensive training to correctly perform and the research is limited in the area. Another technique that we often perform and have had success with is Instrument-Assisted Soft Tissue Mobilization (IASTM). While we have personally seen immediate effects on pain and neural symptoms with this, again the research is limited in the area. References:

Boyd BS, Topp KS, & Coppieters MW. (2013). Impact of Movement Sequencing on Sciatic and Tibial Nerve Strain and Excursion During the Straight Leg Raise Test in Embalmed Cadavers. JOSPT 2013 43(6):398-403. Coppieters MW & Butler D. (2008). Do "sliders" slide and "tensioners" tension? An Analysis of Neurodynamic Techniques and Considerations Regarding Their Application. Manual Therapy 2008 13(3): 213-221. Web. 26 October 2013. Nee RJ, Vicenzino B, Jull GA, Cleland JA, and Coppieters MW. (2012). Neural Tissue Management Provides Immediate Clinically Relevant Benefits Without Harmful Effects For Patients With Nerve-Related Neck and Arm Pain: A Randomised Trial. Journal of Physiotherapy 58 2012. Web. 26 October 2013. Settergren R. (2012). Conservative Management of a Saphenous Nerve Entrapment in a Female Ulra-Marathon Runner. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2013 Jul;17(3):297-301. Web. 26 October 2013.

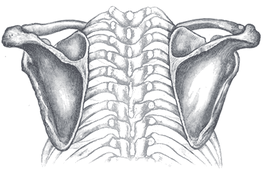

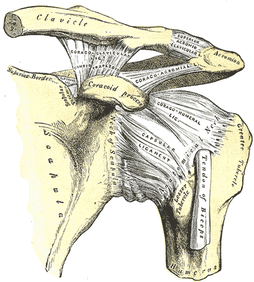

After reading these articles, it would appear that, while there are many hypotheses to the changes in shoulder impairments following thoracic spine manipulation, we still are uncertain about the mechanism. Strunce et al looked at the effect of thoracic and rib manipulations had on shoulder pain in general. The authors found both an increase in shoulder ROM and a decrease in pain. This study, like many others related to this topic, had several methodological errors. There was no blinding, randomization, or control. That doesn't mean the results of this study should be disregarded. It at least should bring the idea of regional interdependence to consideration in your differential diagnosis. Walser et al performed a systematic review for the effect of thoracic manipulations on various musculoskeletal conditions. The authors reported that significant differences were found between those who had a thoracic manipulation and those who did not, in the short-term. In the long-term, there was no difference. Scapular upward rotation is one of the usual suspects in regards to causes of subacromial impingement and rotator cuff tendinopathy. Interestingly, the literature varies on findings of decreased upward rotation to increased upward rotation in these patients (Muth et al, 2012). This study found that thoracic manipulation resulted in minimal decreases in scapular upward rotation, along with little to no change in EMG activity of the shoulder musculature. On the other hand, t-spine manipulation was found to increase shoulder elevation force production and improve both level of function and pain. While no change in shoulder elevation ROM was found, this may have been due to the fact that ROM was measured with weighted glenohumeral elevation. Strunce et al, however, did find an increase in glenohumeral motion following thoracic manipulation. Boyles et al performed an exploratory study on the effects of a single thoracic spine manipulation on subacromial impingement syndrome. While no additional treatment was performed, the authors were able to find statistically significant changes in both pain and disability scores in just 48 hours; however, these results were not found to be clinically significant, based on the established minimal change for clinical significance. The methods of this study were lacking in several areas: low participant number, no randomization, no control group, and more. The authors realized this and emphasized the fact that this study should be used as a launching point for further studies. The fact that significant changes were created after one treatment alone in just 48 hours suggests the potential for a component of care in dealing with patient suffering from subacromial impingement syndrome. Just as manual therapy + exercise was found to be greater than exercise alone for cervical pain, maybe the same applies to these conditions. Additionally, when using thoracic manipulations for cervical pain or lumbar manipulations for low back pain, there exists specific inclusion criteria in order to have the desired results. Again, maybe the same applies to thoracic manipulation for subacromial impingement (or other should pathologies) and we just need to discover the criteria. Sounds like a perfect research opportunity! Obviously, solid evidence on this topic is still lacking, but we hope that this research has at least opened your mind to the possibility of regional interdependence in your patients and maybe treating either the cervical or thoracic spine (or both) the next time you have a patient with a shoulder pathology. References:

Boyles RE, Ritland BM, Miracle BM, Barclay DM, Faul MS, Moore JH, Koppenhaver SL, Wainner RS. (2009). The short-term effects of thoracic spine thrust manipulation on patients with shoulder impingement syndrome. Man Ther. 2009 Aug;14(4):375-80. Web. 15 May 2013. Muth S, Barbe MF, Lauer R, McClure PW. (2012). The effects of thoracic spine manipulation in subjects with signs of rotator cuff tendinopathy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012 Dec;42(12):1005-16. Web. 15 May 2013. Strunce JB, Walker MJ, Boyles RE, Young BA. (2009). The immediate effects of thoracic spine and rib manipulation on subjects with primary complaints of shoulder pain. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17(4):230-6. Web. 15 May 2013. Walser RF, Meserve BB, Boucher TR. (2009). The effectiveness of thoracic spine manipulation for the management of musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17(4):237-46. Web. 15 May 2013.  A 2013 Cochrane review was recently published regarding the effects of Spinal Manipulative Therapy (SMT) for acute low back pain. The review identified 20 randomized control trials with inclusion criteria being adults 18 or older with a mean duration of low back pain of six weeks or less & participants with or without radiating pain. In general the review found that SMT for the outcomes of pain and functional status had low to very low quality evidence. This suggests that there is no difference when treating a patient with SMT vs. another intervention. The conclusion stated that "SMT is no more effective for acute low back pain than inert interventions, sham SMT, or as adjunct therapy. SMT also seems to be no better than other recommended therapies." For someone who is entering an Orthopaedic Residency with a strong emphasis in manual therapy, this information was astounding. I have seen the short and long term benefits of manipulation and mobilization first-hand in the clinic. How could the evidence be so contradictory? When discussing this article with an OCS/ fellow trained manual therapist, he had the following comments to make: "This review like many others on manipulative therapy have similar pitfalls: Operational definitions- Spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) includes every hands on intervention: thrust, non-thrust, mobs, etc. I thinking it would make for a more valid study to really try and separate the types of therapies out. Apples and oranges in my book. SMT alone- we have known that SMT without exercise for low back and neck pain provides very minimal effect. Let’s move on from the thinking that SMT is a panacea and look at what actually happens in the clinic. Minimal subgrouping of patients- classification of patients is vital. Any physical therapist can perform SMT, regardless of training or expertise. Whether the patients are sub-grouped based off of a CPR, patient preference, or therapist experience/critical thinking, not all patients will respond from treatment types the same. After all LBP is a symptom and not a diagnosis. Multiple low quality studies- there is still a void in the literature. Minimal high quality articles regarding SMT are performed by PT’s using the above qualifiers. Therefore, most RCT’s are really just comparing a bunch of low quality research and finding the same conclusions. This study is helpful in that it adds to the body of literature. However, I don’t think it is clinically useful, because it does not adequately describe practice patterns. Humans are extremely complex and manual therapy will only be THE answer in a small subgroup of patients. Everyone else needs a uniquely tailored solution based on the biopsychosocial state, fitness level, and impairments." I found all of these points to be true. Additionally, it allowed me to realize that I too often skim to the conclusion and results section of an article without fully interpreting the research process that goes into finding these results. Understanding the operational definitions and the quality of studies that were researched will alter the authors conclusive points and change your ability to translate this information into a practical clinical setting. The biggest battle which stands between us and our research is the complexity of the human being. We are all so unique. While 2 patients may present the same impairments, there are a myriad number of factors that will go into how they respond to your treatment session. Reference:

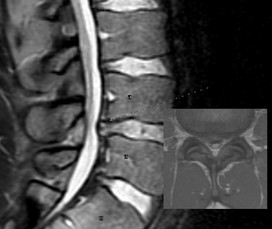

Rubinstein S, et al. "Spinal Manipulative Therapy for Acute Low Back Pain: An Update of the Cochrane Review." SPINE. 2013; 38.3: E158-E177.  While the thoracic spine is often not the source of a patient's symptoms, decreased mobility in this region can create problems up and down the chain. For example, in his book Movement, Gray Cook discusses the importance of thoracic mobility when assessing scapular stability. Additionally, mobility of the ribs, breathing pattern, and referred pain from the cervical spine must all be considered when working with the thoracic spine. In this post from Dr. E, he discusses several innovative techniques to mobilize the thoracic spine. Below is a direct link to the video.  One of the most common pathologies encountered in the health care field is low back pain. It is almost guaranteed that someday in your career as a physical therapist, you will encounter a patient with this diagnosis. With the prevalence of low back pain in our society, there is a large financial drain on the health care system that could be decreased with proper management. The diagnosis of disc herniation as the source of back pain is a controversial issue. There is a large proportion of the population that is asymptomatic and shows disc herniation in MRIs, which leads to the issue of the disc being incorrectly labeled as the source of the patient's complaints sometimes. With the appearance of a herniating disc, some surgeons and patients jump to the conclusion that a surgical procedure is necessary for correction without considering conservative treatment. While surgery can be effective for some individuals, it may represent an expensive overreaction to the patient's symptoms. The study we looked at this week was a systematic review of conservative treatment for lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy. Studies were only included if the patients were over 18 years old and referred with leg pain (with or without low back pain). 75% of the patients had to have a confirmed lumbar disc herniation through MRI or CT as well. Participants with discs that were only "bulging" were not included. Studies were also excluded if surgery was performed or an injection was used; accupuncture, along with other physical therapy interventions, was labeled as conservative therapy. The review found that advice had poorer short and intermediate outcomes for back pain and leg pain compared to surgical microdiscectomy, but there was no difference in the long term. Those who pursued surgery had better function compared to the advice group at short-term follow-up, but no difference was noted at intermediate and long-term outcomes. Manipulation was found to be effective as long as the annulus was still intact. No difference was found between traction, Low Level Laser Therapy, and ultrasound, but traction had good results when combined with electrotherapy and medications in the short term. The review found moderately strong evidence that stabilization exercises were better than no treatment at all. It should be noted that there are possible adverse effects linked between ibuprofen use and traction. While this article offers some information on the effectiveness of various conservative treatment methods in treating lumbar disc herniation radiculopathy, it does not sufficiently examine the entire scope of physical therapy interventions, such as repeated motions, extension based exercises, neuromuscular education of the core, etc. While there are plenty of studies out there that look at the effectiveness of interventions like repeated motions, neuromuscular education, and core stabilization, there weren't many studies looking at those treatment methods that fit the specific inclusion criteria of this systematic review. It does not mean they are not effective, but it points out an excellent research opportunity for anyone interested. Be sure to keep an eye out for some posts coming out in the near future for treating low back pain. Reference: Hahne AJ, Ford JJ, McMeeken JM. "Conservative management of lumbar disc herniation with associated radiculopathy: a systematic review." Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010 May 15;35(11):E488-504. Web. 09/15/2012. |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed