- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

|

Pathophysiology: In 1980, Neer and Foster first coined the term multidirectional instability. They defined it as uncontrolled and involuntary subluxation or dislocation in the anterior or posterior direction of the shoulder. The primary pathology involved can have many potential contributors: excessive capsular redundancy, laxity due to increased elastin density and decreased collagen density, poor osseous configuration such as a flattened glenoid fossa, or weakness in the glenohumeral and scapular musculature that results in poor neuromuscular control (Andrews, Reinold, & Wilk, 2009). Understanding the primary constraints to these movements allows the clinician to have a better understanding of which ligaments and muscles are not functioning properly in MDI. There is little bony stability at the glenohumeral joint and therefore muscles and ligaments act as the primary supporter of the shoulder. Muscle activation patterns have been shown to be different in those with congenital instability compared to normal individuals; the normal force coupling that occurs is absent and the humerus has excessive translation during shoulder movements. There is some debate in the academic community about whether the abnormal muscle patterns are the cause of shoulder instability or shoulder instability leads to abnormal muscle patterns. Recent research is leaning towards the latter. The main structure resisting excessive anterior translation of the humeral head is the anterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL). Weiser et al. found that scapular protraction places increased tension on the anterior band of the IGHL. The main restraints regarding posterior instability include the posterior band of the IGHL and the posterior capsule. The rotator interval provides the main restraint against inferior instability. (The rotator interval consists of the superior glenohumeral ligament, the rotator interval capsule, the coracohumeral ligament, and the IGHL complex). One study we assessed found that subjects with MDI had significantly greater dimensions at the rotator cuff interval and inferior and posterior-inferior portions of the capsule. Additionally, inferior instability (or excessive inferior glide) was a common findings among patients with MDI. As with any other joint, the approximation of various structures can lead to injury of multiple tissue types with an injury (chronic or acute). The axillary nerve, for example, is at risk for injury with instability (the patient may present with abduction weakness). With MDI specifically, patients often present with rotator cuff tendinopathy, subacromial busitis, or secondary impingement syndrome due to the chronic nature of the pathology.

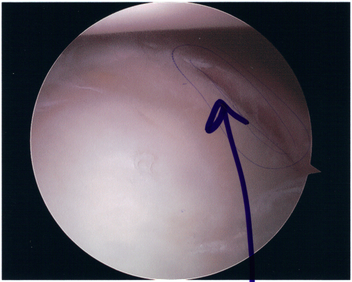

Diagnosis It is important to know the actual definition of Multiple Directional Instability in order to correctly identify individuals suffering from the disorder. There is some inconsistency in the medical field about how to accurately label these individuals. One common set of criteria include: symptomatic excessive translation of the humeral head with respect to the glenoid in more than one direction (Andrews, Reinold, & Wilk, 2009). When an individual suspect of dislocation is identified, often some form of imaging is requested by medical personnel. The initial technique is an x-ray in all common 3 views: anteroposterior, scapular, and axillary (this often doesn't reveal much in patients with MDI). Should some form of bone loss be suspected, a CT is performed to build a 3D image of the shoulder. In order to identify any soft tissue lesions, a MRI is necessary. If performed in the acute stage, a contrast may not be necessary to differentiate the tissues, but a MR arthrogram is the gold standard for viewing lesions in the shoulder related to instability. To further view a specific part of the shoulder's capsular structure, sometimes the imaging is performed in stressed positions: abducted and ER for anterior and flexed/horizontally adducted/MR for posterior. Occasionally, when nerve damage is suspected, some medical professionals prefer to perform a nerve conduction velocity test (and sometimes an MRI) to establish a baseline for nerve function and observe the progression of its healing. Imaging can also be useful in identify individuals with recurrent instability. The normal shape of the glenoid is an inverted comma. With recurrent instability, the glenoid appears like an inverted pear due to osseous destruction. It is important to identify recurrent dislocators, due to the increased incidence of additional pathologies to the shoulder (rotator cuff tears, Bankart lesions, capsular laxity, etc.). As physical therapists, we are unable to order any imaging in most settings. We have to rely on physical exam measures to determine which patients are showing signs of MDI. Patients with MDI will often present with decreased strength and proprioception, especially in the external rotators, scapular retractors, and scapular depressors. Testing ROM can give varied results, depending on the stage of the injury. In the acute stage, patients often have pain or a sense of apprehension that limit end range movement. In the chronic stage, patient may exhibit excessive ROM. As reported earlier, patients with MDI often exhibit increased instability in one specific direction compared to others; therefore, the tests for directional instability may be utilized for these individuals. To identify anterior instability and posterior instability, the examine uses the anterior and posterior instability tests respectively. To assess for inferior instability, the examiner should perform the sulcus sign. Some additional tests utilized include: Clunk test and the Load and Shift Test. Additionally, tests that identify labral pathology can be useful in determining the extent of the injury.  Conservative Treatment: Physical therapy is the first treatment course for patients with MDI. The patient should limit activities that reproduce pain or apprehension, during rehab to allow the tissues to heal. Additonally, the patient should practice proper posture, due to the stressed placed on parts of the capsule with poor posture. Conservative treatment has been shown to be effective in those suffering from MDI due to impaired muscular control or poor control and strength of the rotator cuff and scapulothoracic muscles. Patients with MDI due to bone or labral deformities have not been shown to have good outcomes with conservative treatment. Because shoulder weakness was found in 75% of MDI patients, upper extremity weight-bearing activities have been thought to play an important role in the management of MDI. In addition, rotator cuff, scapular stabilizer, and deltoid strengthening is a necessary component of the rehab program (focus on scapular stabilizers first to establish a stable base). After addressing the scapular stabilizers, the clinician should focus on strengthening the rotator cuff muscles in order to better centralize the humeral head during dynamic activities. Some clinicians prefer initiating rehab with isometric strengthening exercises or isotonic exercises in a limited range in order to allow time for the tissues to heal. Burkhead found that 80% of patients with MDI showed improvements with rotator cuff strengthening exercises. The exercises should be initiated in the scapular plane, as it is the most stable position. This position places the rotator cuff and deltoid in an optimal length-tension relationship and decreases stress placed on the anterior and posterior capsule. Exercises can be progressed to less stable positions, out of the scapular plane. Towards the end of rehabilitation, additional shoulder muscles can be addressed to further develop supporting musculature (i.e. triceps, biceps, etc.). To address the proprioception deficits, rhythmic stabilization drills can improve function of the mechanoreceptors and neuromuscular control in the shoulder by facilitating co-contraction of the shoulder musculature. Eventually, exercises should be attempted in positions of instability to decrease the muscular reflex that occurs in order to lower the likelihood of recurrent instability. Active repositioning tasks, PNF techniques, weight-bearing and plyometric exercises are also used to treat these impairments. The push-up plus, already known to strengthen the serratus anterior, has been shown to activate the subscapularis - an essential component of the rotator cuff force couple. The clinician should always remember to progress exercises in various ways: speed, intensity, frequency, etc. Stretching and PROM should not be utilized in the MDI patient due to the already excessive ROM present in the shoulder. Glenohumeral mobilizations grade III-IV should be avoided as well due to the desire to decrease capsular stress (grades I-II are permitted for pain treatment). It should be noted that conservative treatment may not be advised for all populations. According to Brotzman & Wilk, individuals < 30 years of age who experience a dislocation have a 70% chance of being recurrent dislocators. One study found that those who sought conservative treatment had a 47% recurrent dislocation rate, while those who sought surgical stabilization had a 15% recurrent dislocation rate. Therefore, patients over 30 years of age who experience a dislocation should seek conservative therapy, while patients under 30 years of age should seek surgical treatment. Always be certain of true dislocation. Often, children may present with increased apprehension for instability testing even without dislocation. Surgical Treatment If symptoms persist following a 6-12 month bout of conservative therapy, surgical treatment may be advised for the patient with MDI. Due to the overall capsular laxity, the surgical technique for unidirectional instability is not successful for patients with MDI. Capsular volume must be addressed. According to Dr. Andrews, the gold standard is the open inferior capsular shift. This technique decreases capsular volume by equilibrating capsular tension on all sides and balancing the humeral head. The approach can be anterior or posterior and is usually decided by the direction of greater instability. Those who seek surgical treatment to address instability may have an increased risk of recurrent instability of the direction opposite the approach of the procedure. The capsule can also be addressed arthroscopically (arthroscopic suture capsulorrhaphy). The advantage to the arthroscopic method is that the surgeon can identify concomitant pathologies (labral injury, rotator cuff tear, etc.) and treat them simultaneously. Thermal capsulorrhaphy is a technique that involves administering heat to the capsule with the hope of focusing on type I collagen. It breaks the cross-links and denatures the proteins, leading to a randomized state of collagen - decreasing capsular volume. This method, however, has been shown to have a high failure rate recently and is rarely used today. References:

Andrews, James, Michael Reinold, Kevin Wilk. The Athlete's Shoulder. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier, 2009. 229-236, 556-559. Print. Brotzman, S., & Wilk, K. Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2003. 197-198. Print. Dalton SE, Snyder SJ. "Glenohumeral Instability." Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1989 Dec;3(3):511-34. Web. 10/21/12. Gyftopoulos S, Bencardino J, Palmer WE. "MR Imaging of the Shoulder: First Dislocation versus Chronic Instability." Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2012 Sep;16(4):286-95. Web. 10/21/12. Illyés A, Kiss J, Kiss RM. "Electromyographic analysis during pull, forward punch, elevation and overhead throw after conservative treatment or capsular shift at patient with multidirectional shoulder joint instability." J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2009 Dec;19(6):e438-47. Web. 10/22/12. Kiss, Rita. "Electromyographic analysis during pull, forward punch, elevation and overhead throw after conservative treatment or capsular shift at patient with multidirectional shoulder joint instability." Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 2009. Web. 22 Oct. 2012 Lee, Hui Jen. "Multidirectional Instability of the shoulder: rotator interval dimension and capsular laxity evaluation using MR arthrography." Skeletal Radiology. 2012. Web. 21 Oct. 2012 Ogston, Jena. "Differences in 3-Dimensional shoulder kinematics between Persons with Multidirectional Instability and Asymptomatic Controls." American Journal of Sports Medicine. 35.8 (2007): n. page. Web. 21 Oct. 2012. Swanik KA, Huxel Bliven K, Swanik CB. "Rotator-cuff muscle-recruitment strategies during shoulder rehabilitation exercises." J Sport Rehabil. 2011 Nov;20(4):471-86. Web. 10/22/12. Yamaguchi, Ken. "Management of Multidirectional Instability." Clinics in Sports Medicine. 14.4 (1995). Web. 21 Oct. 2012.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed