- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

A few weeks back, I wrote a post about assessing for Lumbar Extension Rotation Syndrome (ERS) in low back pain patients. Since then I have received several comments from people wanting information regarding treatment options for this condition. Overview A typical patient presentation includes age >55 years old, chronic low back pain, and may be involved in a rotational sport (golf, tennis, etc). On physical examination, you will observe an exaggerated lumbar lordosis, paraspinal muscle asymmetry, excessive pelvic rotation during gait, and hinging during cardinal plane extension testing. They will often complain of unilateral lumbar pain that increases with extension and is relieved with non-weight bearing lumbar flexion. Generally a patient with ERS hyperextends their low back, which does not allow the gluts to fire properly. Treatment For the purposes of this post, I want to focus on core stability and lumbopelvic disassociation. I find that pure hip strengthening is not appropriate early on because the patient cannot adequately engage their gluteals without lumbar compensation. Since the patient has excessive lumbar lordosis and hinging during functional movements, addressing core stability is essential. Additionally, strengthening and motor control of the hip extensors and external rotators is important once the core has sufficient control. Manual therapy is performed on a patient-to-patient basis depending on individual impairments found during the physical examination. Since the patient is generally hypermobile at the hinging segment, they are hypomobilie cranially or caudally. Thoracic and lumbar mobilizations and manipulations are appropriate for the appropriate patient. Core Stability Assuming the patient has low irritability levels and good body awareness, I will usually begin TherEx by retraining the transversus abdominus (TrA) in supine. After the patient can maintain a neutral low back position, I will incorporate the bent knee fall out exercise using a blood pressure cuff for additional cueing. Many progressions of the blood pressure cuff are appropriate until the patient demonstrates good isolation of the TrA in supine. As the patient progresses, I take them through a progression of exercises in quadruped to ensure the patient can maintain a neutral low back posture in a gravity independent position. The progression includes isolated TrA contraction, TrA hand heel rocks (see below), and removing limbs from the table (alternating shoulder flexion, alternating hip extension, then birddog exercises). When the patient can demonstrate good control in quadruped, I address core control in spinal weight bearing. In standing, I have found using the wall as an external cue helps the patient 'find' their TrA. When appropriate, begin functional training in standing by incorporating mini-squats, lunges, and other upper and lower extremity disassociation exercises. Below is a progression of 3 common exercises I prescribe for ERS from supine to standing.

Please let me know if you have any questions or would like more information regarding treatment options of extension rotation syndrome. -Jim

3 Comments

The Selective Functional Movement Assessment (SFMA) is a systematic method that focuses on whole body movement patterns. You might be familiar with the Functional Movement Screen (FMS) created by the same group. The FMS is a screen that can be used by any fitness professional. The SFMA is a diagnostic system (that can only be performed by medical professionals) similar to that of McKenzie. At the core of the SFMA is the concept of regional interdependence, "seemingly unrelated impairments in a remote anatomical region may contribute to or be associated with the patient's primary complaint." The assessment is broken into 7 Top Tier tests and graded as Functional and Non-painful (FN), Functional Painful (FP), Dysfunctional Non-painful (DN), and Dysfunctional Painful (DP). If a Top Tier test does not pass the FN grade, then that specific movement must go to a breakout pattern to find the true cause of dysfunction. To simplify things, the "true cause of dysfunction" can either be viewed as a mobility (Tissue Extensibility Dysfunction (TED)/Joint Mobility Dysfunction (JMD)) OR a Stability/Motor Control Issue (SCMD). Below is an example of Chris performing the Multi-Semental Flexion Top Tier Test with demonstration of the appropriate breakout patterns following. In the Multi-Segmental Flexion Top-Tier test, have the patient bend forward to touch their toes. The person assessing the movement should be looking for a uniform spinal curve, the thoraco-lumbar junction ending up over the feet, a sacral angle >70 degrees, and the ability to touch the toes without excessive exertion. If the person passes all the listed criteria, they are considered FN! Otherwise they are graded as DN, DP, FP and the Multi-Segmental Flexion breakout needs to be performed. As you can see, Chris is unable to touch his toes, so he is immediately given a DN (the motion was pain-free). At this point, we know they have some type of dysfunction. Whether it is a posterior chain extensibility issue or motor control issue, we are not sure. Therefore we must continue with the assessment. The next video (below), demonstrates the Single Leg Forward Bend. This will give you a sense if the dysfunction is symmetrical or not & if a single leg movement produces pain. In order to "pass" this test, the same criteria as above need to be fulfilled. All this test really tells you is if there is an asymmetry or not. As you can see below, Chris' movement is still DN, so the breakout continues (it would continue even if he received a FN). At this point, we know Chris has a dysfunctional movement pattern in standing so we need to see if the movement changes when he is placed in NWB. This tells us if he simply has a postural control issue. The next test (seen below) is the Long Sitting Test. To pass this test, Chris needs to touch his toes, have a sacral angle of at least 80 degrees, and have a uniform spinal curve. You will see in the video that he cannot touch his toes and the sacral angle does not reach 80 degrees. He has no pain, so the movement is graded DN. Hypothetically at this point, if Chris were to have passed (FN), we could assume he has a SMCD due to an issue with postural control because he is able to perform the motion once the effects of spinal loading have been reduced. He would then proceed to the Rolling component. Since Chris is unable to complete the motion when postural control is decreased, we now break apart each component of the motion to determine where the fault lies. To first assess the lower extremity component, we move to the Active Straight Leg Raise (seen below). This motion assesses the motor control/stability to actively flex the lower extremity, provided there is sufficient range. A minimum of 70 degrees of hip flexion is required. Be sure to watch that the contralateral thigh stays down and the knee remains extended on both legs. As you can see, Chris does not reach 70 degrees, so he receives a grade of DN. If Chris were able to complete this motion, we would know that Chris has adequate tissue/joint mobility and motor control in his lower extremities. We would then move on to the Prone Rocking Test. With Chris failing to pass the Active Straight Leg Raise, we must now move onto the Passive Straight Leg Raise to determine if the tissue/capsular length even exists for the motion to complete. A passing score would require 80 degrees of hip flexion (with the same precautions in the active test). Chris again does not pass the test (DN). If he had passed this test, we would then proceed to Rolling. After determining that there was a TED or JMD limitation, we can now use the Supine Knee to Chest test to determine if it is a 1 joint or 2 joint limitation (it could potentially be both). As you can see with Chris, he has a 1 joint limitation for sure (he likely has a 2 joint deficit as well) - DN. This positive test may indicate capsular hypomobility, decreased length of the gluteus muscles, or decreased neural mobility (or a combination). This is a location for treatment with Chris. Going back to the Active Straight Leg Raise Test, had Chris passed it he would have proceeded to the Prone Rocking Test below. With the lower extremity component of the Multi-Segmental Flexion Top Tier Test ruled out, we now need to assess the other primary component: lumbar flexion. A passing test requires a uniform curve and the thighs pressing against the lower rib cage. With the lower extremity motion already cleared, we now know the restriction if located in the lumbar spine as a TED or JMD. With the video below, it appears Chris receives a DN, but remember he had limited hip flexion, which can cause a false positive here. As you can see, the sequencing is important! Assuming this test receives a FN, we once again proceed to Rolling. Had your patient had a DN score here, this would again be a location of treatment for JMD or TED. Finally we arrive at the rolling pattern. once we have shown that adequate joint/tissue mobility is present for the required pattern, we can assess motor control patterns with this breakout. Look for your patient's ability as to whether or not they can complete the flexion rolling patterns. The motions should be smooth with dissociation of each component (you should not see log-rolling). Limited mobility anywhere in the chain can cause pauses or difficulties completing the motion (i.e. decreased cervical rotation could easily inhibit normal rolling, especially since it is the starting point for UE flexion rolling. Rolling can be scored just as the other tests. FN requires pain-free smooth rolling with no difficulty, pauses, or inability to dissociate the components - any of these lead to DN. DP and FP follow the usual scoring roles as well. Hopefully this gives you an idea of what the SFMA offers as a method of doing examination. This doesn't mean you should exclude your strength tests, special tests, neuro screens or even ROM measurements for certain patient populations. In a way, this method is even more objective than a goniometer allows due to the system's utilization of actual landmarks for completion. A goniometer may still have a place where regular progress is required (i.e. surgical patients, adhesive capsulitis, etc.). Instead this system can help to gain a very detailed look at each patient and ensure that you don't miss anything significant. Your patients often will comment how thorough you are (making you look like an even better PT!). The rest of the SFMA has a similar process of going through joint-by-joint assessments of motion and stability for the rest of the body as well. If you are interested in this, you may want to take the SFMA course. Gray Cook's book Movement details the system as well; however, the system has actually been updated since the book was written and is much more thorough and appropriate now. This method of examination has helped us to better determine the best locations for treatment and other potential causes to dysfunction. If you have any questions, do not hesitate to ask!

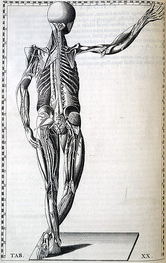

We may have touched on Lower Crossed Syndrome in the past, but it is seen so frequently that is does not hurt to mention it again. Lower Crossed Syndrome is a common musculoskeletal disorder related to postural imbalances. In this syndrome, the patient will often present with short/strong hip flexors and lower back extensors. Contrarily, they will have lengthened/ weak abdominals and gluteal muscles. These diagonal patterns of imbalance create an imaginary "X" on the patient (hence the name "crossed" syndrome). This syndrome is typically seen in people who sit for long periods of time, allowing the hip flexors to shorten. Additionally, it can be found in athletes who use repetitive movements such as running. Clinically you will see an anterior pelvic tilt, lumbar lordosis, lateral rotation of the lower extremities, genu recurvatum, and alterations in arm/leg swing patterns during gait. The anterior pelvic tilt and lumbar lordosis may create increased compressive forces along L4, L5, and S1. Any compromise of the lumbopelvic muscles may lead to instability throughout the lower extremities, so your patient may present with low back pain, knee pain, or ankle issues. For example, the gluteus maximus is an important eccentric decelerator for hip flexion, internal rotation, and adduction. If the gluteus maximus is weak, it cannot stabilize the tibiofemoral joint properly during dynamic motion. Additionally, the tight hip flexors are placed in a better position for muscle contraction and consequently receive increased neural input. This reciprocal inhibition can lead to further tibiofemoral instability and knee pain. When treating these patients, postural awareness, lifestyle modification, stretching, and strengthening will be important. Remember to address the shortened muscle prior to intensive strengthening. The patient needs to have adequate muscle length before beginning a strengthening program. Also, always direct your attention to the cause of the patients symptoms. While they may be having regional symptoms, the true cause may be either proximal or distal to the symptoms.  This is part 1 of Dr. E's blog post on treatment options to improve the overhead deep squat. Many components are involved in the deep squat which makes understanding the true cause of an inadequate performance difficult. The motion requires adequate hip extensor length, thoracic extension, ankle dorsiflexion, stability of the scapulothoracic musculature, and more. Both mobility and stability must be present in order to successfully complete the movement. With adaptive shortening of the hip extensors (especially the hamstrings), you often see difficulty maintaining proper lumbar position, leading to an excessively forward flexed torso. Thoracic extension and shoulder mobility combined with scapulothoracic stability are crucial for maintaining an upright posture while descending into the deep squat. Again, a deficit in this area often involves a forward flexed torso. Ankle dorsiflexion is necessary to prevent heel rise during the deep squat. We often see an adjustment for this in the FMS using the 2x6 wooden board to bring the ground up to the heels. Core stability is an obvious necessity as it contributes to maintaining proper posture during the movement. The components required for completion of the movement go on, but these are some common impairments. Dr. E outlines 5 treatment options: 1. Thoracic spine manipulation to help improve thoracic mobility and glenohumeral motion. 2. Subscapularis Release for shoulder mobility. 3. Psoas Release: He demonstrates a great new video on a new psoas technique that is much less invasive and utilizes the principles of the neurophysiological effects of muscle tone. 4. IT Band Release using the edge tool to help increase hip mobility 5. Tibial Internal Rotation Mobilization with Movement for both knee and ankle mobility. He describes how the lower leg often is put into relative external rotation due to hip weakness, medial rotation of the femur, and pronation of the foot. He demonstrates each of these techniques with good clarity. Although he is using these techniques in relation to the overhead deep squat, you can see how they would apply to any patient with deficits in that region.  Introduction: Low Back Pain is one of the most common musculoskeletal conditions with a lifetime prevalence between 70-85%. Ninety percent of the population will improve, but the other 10% will go on to develop chronic low back pain (cLBP). Known as a "Western Epidemic," it is estimated that the total costs of LBP each year amount to 100 billion dollars in the United States alone (Tsoa 2008). Chronic pain is defined as pain lasting longer than 6 months that is not related to a malignancy. Our current belief of pain roots from the traditional medical model that pain is a "physical response to an organic dysfunction (Wolff 1991)." Throughout the medical community there has been a push to change that traditional thinking pattern. New pain models are being produced with reliable data to support their findings. CLICK HERE TO READ MORE ABOUT THE MANAGEMENT AND TREATMENT OF CHRONIC PAIN One of the common findings in individuals with low back pain is poor utilization of the core musculature. The TA (transversus abdominus) has been found to be highly suspect in these cases. Any activity that involves movement of the extremities, first requires some sort of weight shift (it may be small) to assure stability. This is usually accounted for by a contraction of the TA right before the movement of the extremity. Studies have found that individuals with low back pain have delayed recruitment and decreased motor firing of the TA in activities. A common therapy technique in individuals with low back pain is to provide neuromuscular education on how to first fire the TA (and other core muscles) and then utilize them during daily activities. The theory is that since the TA encircles the abdomen/core (when combined with the internal obliques) and connects to the thoracolumbar fascia. When the TA contracts, it stiffens the fascia and creates a stabilized cylinder that is the core! There have been many exercises developed with the focus on isolating and educating usage of the TA, such as pelvic tilts. This study looked at the potential for using co-contraction to increase the motor control of the TA. The researchers found increased activity and thickness of the TA when resisted ankle dorsiflexion was combined with the abdominal draw-in maneuver. While the results are very interesting, there are many things that should be considered when examining this study. First of all, the study had a low sample of participants at 40 individuals that were conveniently selected. The measuring of TA baselines and improvements were questionable as well. Surface EMGs were used to measure activity and can receive interference relatively easily from other muscles due to their proximity. Ultrasound imaging was used to measure the thickness of the TA and other abdominal musculature. The methods to this study were questionable, but the results provided interesting findings that could potentially be incorporated in future studies and interventions. Anatomy Review ("Kendall"): Transversus Abdominus (TA): Origin: inner surfaces of cartilages of the lower 6 ribs, interdigitating with the diaphragm; thoracolumbar fascia; anterior 3/4 of internal lip of the iliac crest; and lateral 1/3 of the inguinal ligament. Insertion: linea alba by means of a broad aponeurosis, pubic crest, and pecten pubis. Innervation: T7-12, L1 iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal, ventral divisions. Action: acts like a girdle to flatten the abdominal wall and compress the abdominal viscera; upper portion helps to decrease the infrasternal angle of the ribs, as in expiration. This muscle has no action in lateral trunk flexion, except that it acts to compress the viscera and to stabilize the linea alba, permitting better action by the anterolateral trunk muscles. References:

Chon SC, You JH, Saliba SA. "Cocontraction of ankle dorsiflexors and transversus abdominis function in patients with low back pain." J Athl Train. 2012;47(4):379-89. Web. 09/28/2012. Kendall F, McCreary E, Provance P, Rodgers M, Romani W. "Muscles: Testing and Function with Posture and Pain." 5th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005. 197. Print.  Image Courtesy of JOSPT It seems today that every movement dysfunction can somehow be related to a deficiency in core stability. While this is an exaggeration, the importance of core strength and endurance has become a hot topic in recent research and should be carefully evaluated with many of your patients. This article does a nice job exploring the various core strengthening exercises that we often prescribe patients. The article highlights muscle activation of the upper and lower rectus abdominus, external oblique, internal oblique, lumbar paraspinals, latissimus dorsi, and rectus femoris muscles during common therapeutic exercises. It demonstrates which exercises elicit the highest maximum voluntary isometric contractions and how to get the most bang for your buck when selecting core interventions. Highlights: -The Roll-out Exercise and Pike Exercise were the most effective in activating core muscles. -Prone Position swiss ball exercises were as effective as kneeling and supine exercises. -The traditional crunch has fairly high upper rectus abdominus muscle activation, but lower activation in the internal oblique, external oblique, and lower rectus abdominus. Muscle Review:

|

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed