- Home

- About Us

- TSPT Academy

- Online Courses

-

Resources

- Newsletter

- Business Minded Sports Physio Podcast

- Day in the Life of a Sports PT

- Residency Corner

-

Special Tests

>

-

Cervical Spine

>

- Alar Ligament Test

- Bakody's Sign

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test

- Craniocervical Flexion Test (CCFT)

- Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test

- Posterior-Anterior Segmental Mobility

- Segmental Mobility

- Sharp-Purser Test

- Spurling's Maneuver

- Transverse Ligament Test

- ULNT - Median

- ULNT - Radial

- ULNT - Ulnar

- Vertebral Artery Test

- Thoracic Spine >

-

Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joint

>

- Active Sit-Up Test

- Alternate Gillet Test

- Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test

- Extensor Endurance Test

- FABER Test

- Fortin's Sign

- Gaenslen Test

- Gillet Test

- Gower's Sign

- Lumbar Quadrant Test

- POSH Test

- Posteroanterior Mobility

- Prone Knee Bend Test

- Prone Instability Test

- Resisted Abduction Test

- Sacral Clearing Test

- Seated Forward Flexion Test

- SIJ Compression/Distraction Test

- Slump Test

- Sphinx Test

- Spine Rotators & Multifidus Test

- Squish Test

- Standing Forward Flexion Test

- Straight Leg Raise Test

- Supine to Long Sit Test

-

Shoulder

>

- Active Compression Test

- Anterior Apprehension

- Biceps Load Test II

- Drop Arm Sign

- External Rotation Lag Sign

- Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Sign

- Horizontal Adduction Test

- Internal Rotation Lag Sign

- Jobe Test

- Ludington's Test

- Neer Test

- Painful Arc Sign

- Pronated Load Test

- Resisted Supination External Rotation Test

- Speed's Test

- Posterior Apprehension

- Sulcus Sign

- Thoracic Outlet Tests >

- Yergason's Test

- Elbow >

- Wrist/Hand >

- Hip >

- Knee >

- Foot/Ankle >

-

Cervical Spine

>

- I want Financial Freedom

- I want Professional Growth

- I want Clinical Mastery

Recently, The Manual Therapist wrote a blog post about what is most important when treating a patient: the what, the why, and the how. To relate it more directly, what you have refers to specific diagnoses. Why you have it refers to the theory of why the pathology occurred, i.e. movement impairment syndromes. The how refers to how we actually treat and assess. Much of medicine and physical therapy is often stuck in the "what" phase. We tend to assign diagnoses to tissue pathology and often look to treat what we believe is the source of the pain, not the original cause. Many physical therapists are moving towards the "why" mindset where we look at a more complete chain of the body to determine why our patients are in pain. This typically leads to a more well-rounded treatment approach. The "how" comes back to what we are actually doing and how we are treating our patients. I recommend reading the original post by Dr. E to get further clarification. This post comes with good timing in the wake of Tiger Woods' "sacrum" comments. In case you missed it, Tiger Woods recently played in a golf tournament and had to withdraw, because he claimed his "sacrum went out." As a result, there was a backlash from much of the young PT community claiming how it was a horrible diagnosis, Woods' physical therapist had poor communication skills, etc. The discussion lead to many physical therapists and physical therapy students ranting about how the research for SIJ Dysfunction as a diagnosis is poorly supported based on higher level evidence (which is correct) and some even saying how the SIJ doesn't move at all. Based on these comments, it would appear many do not assess or treat the Sacroiliac Joint. While I may agree that we shouldn't worry about actual tissue diagnoses, I get frustrated by people's reluctance regarding any potential SIJ treatment given my personal clinical success. In the residency at Scottsdale Healthcare, we were taught various assessment and treatment techniques for the SIJ, but the distraction manipulation could be used as a "shotgun" approach and treat typically any form of SIJ dysfunction. In my limited experience, in the patients I feel would benefit from the manipulation, they tend to be 100% within just a few visits. Now a manipulation by itself is never the answer alone, but it can be an extremely useful tool. We need to build on preventing future recurrences of pain and teach our patients to maintain improvement independently. Some patient's arrive at clinic in excruciating pain and are nearly pain-free after manual treatment. A manipulation and mobilization are not the only potential treatment for what some would diagnose "SIJ Dysfunction." Repeated motions towards the directional preference may be appropriate as well. Basically, many of treatment techniques like these have theories to support them, but the evidence is not always as established. That doesn't mean successful treatment techniques should be discounted. I again recognize our limited ability (and importance) of truly diagnosing what we think we see with the SIJ, but I must continue to stress the impact of when we assess, treat, and reassess. This is the importance of the how I discussed at the beginning. If the patient feels better immediately after a treatment technique, something I did had the desired effect! We currently are unable to be certain in knowing the exact mechanism our techniques have, but we should not ignore positive results. I have written extensively in the past about the problems with the studies regarding manual therapy, especially the SIJ, but that is not important in the end. What is important is that we find effective ways in getting our patients better as soon as possible. If that means doing a manipulation or mobilization where we think we are targeting the SIJ, then so be it. Do not let the limitations in higher level research prevent you from providing your patients with the most effective care. -Chris

17 Comments

As you know, we have reported in the past about using the edge mobility band for things like increasing hip IR, tibial IR, or ankle DF with MWM techniques. It's success is primarily based upon the theory that it engages mechanoreceptors and alters fascial mobility via changes in sympathetic nervous system. Additionally, it enhances the grasp by the clinician for MWM. Recently, I had a couple of instances where I tried using the mobility band that I had not previously trialed. In one case, I was treating a patient s/p ACL reconstruction just a couple weeks out. She was presenting with significantly limited flexion ROM secondary to medial thigh and proximal tibia pain. These aren't your traditional pain locations from surgery and led me to believe it was more neural-based. The next session, I applied a mobility band over the thigh and over the proximal tibia. The patient immediately reported she no longer had pain. This allowed the patient to tolerate PROM and her exercises much better. The second case was a patient who had reports of neural symptoms and a sensation of "weakness" in his UE. He had been responding, albeit slowly, to IASTM with his symptoms decreasing. On his last treatment session, a mobility band was applied over his affected UE near the elbow for his exercises. The patient reported he was able to complete all exercises with no abnormal sensations in his UE. Being able to change our patient's symptoms with the bands can be crucial to maximizing their time in treatment. Our patients can tolerate manual therapy and exercise better, thus possibly allowing for larger gains. Check out the pictures below to see where I applied the bands. Depending on your patient's presentation, a different application may be required.

-Chris The last month or so I have been using repeated motions consistently in my evaluations and treatments. Like many other PT's, I was taught McKenzie in school basically was lumbar extensions and only applied to a select few patients. The misunderstanding of how repeated motions work and should apply to our patients is probably one of the most significant disservices we are doing to our patients. Since incorporating them into my care (thanks to The Manual Therapist), I have noted significantly greater improvements in less time. Now I do not have a full understanding of the system based on MDT, but this post will link to several posts by The Manual Therapist so you can learn to apply it tomorrow. Let's start of with why you should be using repeated motions in your exam. With about 90% of our patients being rapid responders, we should be getting immediate improvements on the day of our examination. Repeated motions are easy, reliable, have built in testing, lead you to treatment and give you your HEP. You will notice with application of these principles, for the appropriate patient you will be amazed at how much better your patients get faster. Now what exactly is that about MDT and repeated motions that makes it so effective. Let's start with some of the misconceptions about MDT. MDT does benefit from some manual techniques. While I like repeated motions because it makes the patient more independent and gives them their HEP, sometimes they are unable to get the patient 100% of the way there. A manual technique may get that extra bit or may even accelerate improvements in another area. The MDT theory is not based on disc model like what is taught in school. With modern pain science showing how much force is required to deform tissues and how much normal degeneration solidifies different tissues, we must realize that we are not actually affecting the disc. These "disc" injuries are often associated with McKenzie extension exercises, leading to the stereotype that MDT is extension. This couldn't be further from the truth as repeated motions can be applied to any direction and any joint (the link there has a video that shows various resets for repeated motions at different joints). So how are the changes acquired with MDT? One of the prime components of why MDT works (per one hypothesis) is because the repeated loading of the joints engages mechanoreceptors enhancing proprioception. This may alter the patient's perception of their ability to go into what was a painful motion. What is necessary for repeated motions to actually work is to actually get to end range. We all have seen mobilizations and manipulations have improvements with our patients. There are different theories as to how these changes actually occur, but one of the necessary components is that end-range is required. Repeated motions have the benefit of making the patient independent with their care and allows a patient to maintain any gains acquired from PT. We may not improve ROM in all patients due to degeneration, but pain or other symptoms can still improve. It is often difficult for patients to get to this end-range out, because more often than not the direction that is prescribed is the painful one. With each motion in the correct direction, the patient will realize that it is okay to move into that direction and lower their fear avoidance. How do we choose which direction to proceed? The treatment choice is based on the directional preference. The directional preference is the direction that a joint needs to be repeatedly loaded to have effects potentially on ROM, pain, DTR's, strength, and function. The direction is more often than not the direction the patient tends to avoid. When trying to find the directional preference for sure or when distributing a repeated motion as part of an HEP, it is essential that you remember the stoplight system. The stoplight system allows you and the patient to monitor the progress of symptoms ensuring the correct exercise was given. A green light is when the symptoms centralize and remain better. It is still a green light if the pain centralizes but increases centrally, because it is still centralizing! A yellow light is when a patient's pain or symptoms increases but they can "walk it off." What we must realize with yellow lights is that maybe a patient's pain will increase, but in doing so they have greater motion or greater motion before the pain occurs. It is easy to become hesitant with yellow light responses, but we must remember that we need to get to end-range to have the desired effect. A red light is when a patient's pain or symptoms worsen but cannot be "walked off." Hopefully this helps to summarize some of the concepts of repeated motions and MDT. I encourage you to look at each one of the links for further information and better understanding of repeated motions. For more information, check back on Dr. E's blog regularly in order to enhance your understanding in the area. He often has posts like this that may show you how to incorporate MDT into your clinical reasoning. In doing so, you likely will notice rapid improvements with many of your patients. -Chris

A couple months ago, I subscribed to the premium portion of The Manual Therapist. Dr. E presents a very eclectic approach with various techniques with which I had not been familiar. One of the prime components of Dr. E's assessment and treatment techniques includes repeated loading. While this might be associated with the McKenzie school of thought, his reasoning has more of a neural approach. Since my neck hurt more on one side, I wanted to look for an asymmetry to treat. With cervical retraction and sidebend, both sides were painful, but I was especially limited to the R. Noting the asymmetry, I proceeded to perform repeated motions in the limited direction which resulted in increased range and decreased pain. Part of the theory is that by getting to the end-range repeatedly, we can re-teach the nervous system that it is okay to go in that direction and possibly others. A common saying for McKenzie type exercises is 10 repetitions 6-8 times a day. With Dr. E's approach, the more the motion is performed, the better. This applied to me. I noted the more I did the exercise, the longer I could go without pain and with increased motion. That evening I had my girlfriend do a cervical manipulation and thoracic manipulation which helped my pain, but within 30 minutes, I was back to the prior levels. The next 2 days, I did the cervical retractions and right sidebend 10x every 30 minutes throughout the day (give or take). Each time I did the exercises, I found I could go longer before the pain and stiffness returned. After 48 hours, I was 95% better.

There are two important components I took from this experience. First, repeated loading can be an incredibly useful assessment and treatment technique, when applied properly. With the majority of people being rapid responders, we should get almost immediate changes with pain and/or motion. Secondly, it is frustrating how long we often have to wait for patients to be evaluated due to length of time after referral, lack of awareness of what PT can offer, or other reasons. The sooner patients can access physical therapy, the sooner physical therapy can begin to help patients on the road to recovery. -Chris

Next, I recommend a reassessment of the structures that were targeted during the initial evaluation. For example, if I found decreased mobility of the AA joint on the eval day, I would definitely be sure to reassess that prior to performing a manipulation - if warranted. With daily activity, joint mobility, flexibility, etc. can easily change due to something that happened between treatment sessions. And if a previously hypomobile joint is now normal, why mobilize it? Now I am not saying we should perform a complete re-examination of the objective section, but if the plan for the day involved manual therapy, I recommend assessing the targeted structures first. In cases like SIJ Dysfunction, maybe you reassess the pelvic alignment each session. How thorough you need to be is determined by dysfunction location, severity of injury, and various individual patient factors.

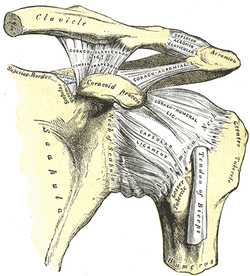

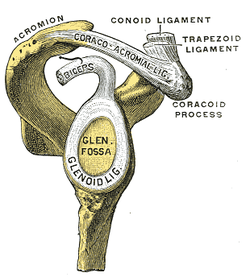

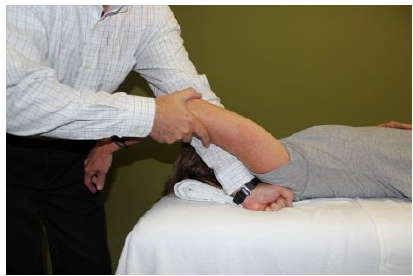

After finding the dysfunctional areas of mobility, I typically perform my manual therapy. My goal is to give the patient as much mobility in the limited structures as possible to the norm. Any limitation can lead to a compensation of hypermobility in adjacent or distant structures that may be the source of the pain. With the sedentary aspects of our lives, degeneration has become an expected normal development. While we would like to acquire true normal motion in everyone, it is not always feasible. I should note that some clinicians may prefer the patient do a warm-up prior to manual therapy or the reassessment as that may have an impact on treatment performance and clinical findings. Personally, I determine the need of a warm-up based on each individual patient. (I also should note not every patient requires manual therapy). Once I have completed my manual therapy, I go back to reassessing. Is the previous hypomobile joint now hypermobile? Is the previously painful motion or action now pain-free or less painful? We need to be certain our manual therapy had the desired outcome. As Nick Rainey states in a previous guest post, this is know as an asterisk sign (test-treat-retest). We may find that our previous assessment was inaccurate or that we need to spend a little more time with manual therapy in order to reach our goal. It is at this time that I proceed to therapeutic exercise/neuro re-ed. I truly believe it is important to complete your manual therapy first before moving this stage. With manual therapy, we often acquire new ranges of motion due to changes in joint mobility/tissue length/neural tension. While this is important, it is essential we use exercises to lock in the changes. We must retrain the body to move in those new ranges; otherwise, we are setting the patient up for re-injury. As Gray Cook has said, our bodies adapt dysfunctions often as a form of protection. If you free up the dysfunctional tissues, you are putting the patient at risk. Finally, I recommend finishing up each treatment session with another subjective portion. See how the patient immediately responds to that day's work. Some treatments have an immediate effect and again can impact our plan for the next session. As is typical, every patient is different and may require a different sequence for the treatment. This is merely an outline of how I work with my orthopaedic patients typically. There are more than a few indicators for adding, subtracting, or re-ordering the plan for that day! -Chris  General Overview Acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) injuries are quite prevalent throughout the general population and specifically in the athletic population. In 2012 Harris et al found that ACJ disease was present in 31% of individuals who presented with shoulder pain. (Harris 2012) The ACJ is a synovial joint which connects the distal clavicle to the acromion process. The joint assists the scapulothoracic joint in full rotation to adjust for changing elevation of the humerus. Composite motion of the ACJ and sternoclavicular joint (SCJ) contributes up to 60 degrees of upward elevation, 15-30 degrees of posterior tipping, and 15-25 degrees of external rotation during arm elevation (measuring the motion at the ACJ is difficult and typically not done because the kinematics are not well defined). What we do know is that kinematics at the ACJ affect the "quality and quantity of movement at the scapulothoracic joint." (Neumann 2010) With motion occuring in 3 planes, the ACJ lacks stability and relies on 3 major ligaments for support. The acromioclavicular ligament and coracoclavicular ligaments (conoid and trapezoid) support the joint and resist horizontal stresses and limit superior translation respectively. These ligaments have fascial connections with nearby muscles, specifically the trapezius and deltoid. In a high grade AC joint separation, a clinician will often find these muscles injured as well. The resting position of the ACJ is the arm at the side and the closed packed position is full elevation. Due to the high prevalence of dysfunction, assessing the ACJ needs to be a priority during an initial evaluation with a patient who presents with shoulder pain.  Manual Therapy Now that we know more about the ACJ, how can we treat this joint when suspecting hypomobility? Since the ACJ is a planar joint, normal concave/ convex rules of manual therapy do not apply. Therefore, we must use our clinical judgement as to when and why to perform joint mobilization or manipulation. A major factor to consider is the patient's acuity. (The novice clinician should be aware that acute ACJ separations do not require intense manual therapy because of the acuity of their symptoms and the laxity present in the region.) Generally in more acute stages, posterior to anterior ACJ mobilizations in supine with the arm resting at the side are effective (left picture below). Remember, this is the resting position of the joint as well allowing for more mobility. As the patient's ROM and strength progresses, more intense manual therapy can be performed. For example, certain patients may only have pain and limitations at end range of motion. To reach full humeral flexion and external rotation at least 30 degrees of upward rotation and 8 degrees of external rotation is needed. (Teece 2007). An example of a more advanced manual technique is a posterior to anterior mobilization at end range using the arm as a lever. In this position, the therapist's hand blocks movement of the distal clavicle so that acromion is mobilized on the stabilized clavicle. Small oscillations of the humerus are made at the end-range promoting movement at the ACJ. There are many more mobilization and manipulative techniques and positions that can be performed at the ACJ. Hopefully this post gave you an insight into a beginner and a advanced mobilization technique. -Jim References:

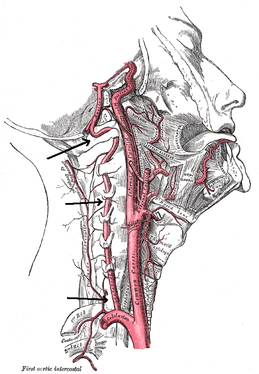

Harris, Kevin D., Gail D. Deyle, Norman W. Gill, and Robert R. Howes. "Manual Physical Therapy for Injection- Confirmed Nonacute Acromioclavicular Joint Pain." Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 42.2 (2012): 66-80. Print. Neumann, Donald A. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System: Foundations for Physical Rehabilitation. St. Louis: Mosby, 2002. N. pag. Print Teece, Rachael M., Jason B. Lunden, Angela S. Lloyd, Andrew P. Kaiser, Cort J. Cieminski, and Paula M. Ludewig. "Three-Dimensional Acromioclavicular Joint Motions During Elevation of the Arm." Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 38.4 (2008): 181-90. Print.  There is a common fear in treating the cervical spine (especially the upper portion) manually due to risk of injury. With the potential for damaging the vertebrobasilar artery system in the cervical spine, many people stray away from performing cervical manipulations. There have been a few situations where patients have died of ischemia following a cervical manipulation. The fatal reaction (and associated risk for lawsuit) to something that we can do as health care practitioners may discourage some from learning how to effectively apply manual therapy to the region. Is there really that much risk to injury? And what can we do to assess it? As with any fatalities in the health care system, media (and other professional disciplines) will try to make the public aware of the risk for injury following a treatment. The same case applies to cervical manipulations. Some people have a somewhat irrational fear of this technique following media coverage and word of mouth. But how much risk is there really? NSAIDS have a .0004% annual mortality rate (Vizniak 2015). There is a .00005% chance of dying from a lightning strike each year. With cervical manipulations, there is a .00002% risk of death. This means you are more likely to die from taking NSAIDS or being struck by lightning than a cervical manipulation. That being said, it is essential that proper patient selection is done before even considering this type of treatment technique. Start with patient history. Any patient with ligament laxity, rheumatoid arthritis, long-term corticosteroid use, osteoporosis/-penia, Down's Syndrome, osteoarthritis, and VBI be excluded. Naturally, we should perform our structural integrity tests and blood flow tests. We recently completed a review of the upper cervical spine that may prove beneficial reading as well. The structural integrity tests should at least include Transverse Ligament Test (and/or Sharp Purser Test), Alar Ligament Test, and a test for a Jefferson's Fracture. This last test is completed by compressing the transverse processes of the Atlas to assess for integrity. A positive test will occur with lack of stability or reproduction of neural symptoms. The artery test that is commonly performed is for Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency (VBI). While the test we show displays combined end-range motions, some say this is not necessary. With the manipulation techniques staying closer to mid-ranges, some suggest just performing complete rotation when assessing. In theory, combined rotation and extension significantly closes off the vertebral arteries greater than rotation alone. Now, the real question is: should we perform the Vertebral Artery Test? A compilation of studies revealed that there is a 0% sensitivity and .67-.90% specificity for the test (Cope et al, 1996). What this tells us is that a negative test means absolutely nothing and a positive test means a patient may have VBI. The testing we perform cannot rule out or rule in VBI. Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency is essential to consider as many of the symptoms mimic other orthopaedic cervical spine conditions: headache, neck pain, etc. (along with more traditional VBI symptoms - see link for symptoms). Even though there is poor diagnostic accuracy associated with the Vertebral Artery Test, it is recommended that the test be performed. There is a traditional thought that the vertebrobasilar artery system be tested prior to any manual therapy, no matter how poor the test is. Due to the media's perception that cervical manipulations risk VBI, any sign of "negligence" by not performing the test would likely place blame on the practitioner. As with any treatment technique, evaluate each patient individually for the potential benefit and associated risk factors prior to performing. In addition to performing the VBI test, Jim and I agree that the therapist should perform a pre-manipulative hold prior to any thrust procedure. The pre-manipulative hold allows the therapist to see how the patient will respond to the manipulative position prior to performing the thrust technique. Finally, we recommend following that process up with a "gut check" as well. Is the risk of the technique worth the reward/ benefit the patient will experience? Not everyone needs or should have a manipulation, but there are some instances where it has been shown to be highly beneficial. -Chris References:

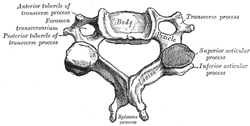

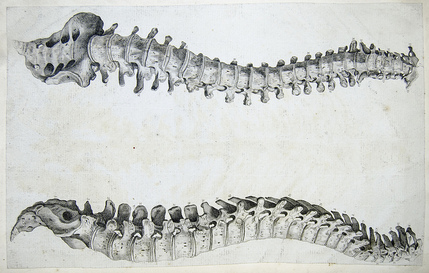

Cote P et al. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1996. Vizniak, Nikita. Spinal Manual. Canada: Professional Health Systems, Inc, 2015. 156-157. Print.  Individuals with mechanical neck pain often have pain and a loss of mobility in the upper cervical spine, specifically at the atlanto-axial (C1-C2) joint. This joint is primarily responsible for cervical rotation, but also contributes to small amounts of flexion and extension. Arthrokinematically, during left rotation, the left facet of the atlas(C1) glides posterior on the axis (C2) & the right facet of the atlas glides anterior. During flexion, the facet of the atlas glides anterior and rolls posterior in relation to the axis. The opposite happens with extension. There are 2 different theories as to how to assess the mobility of C1-C2. At Harris Health, I learned to maximally side bend the head, followed by opposite rotation. For example to assess C1-C2 rotation to the left, maximally side bend the head to the right, followed by maximal rotation to the left. The maximal side bend "locks out" the lower cervical vertebrae allowing for motion only at the C1-C2 junction. The other method to assess C1-C2, which I learned in PT school at St. Louis University, is the flexion- rotation test. To perform this test, maximally flex the cervical spine followed by maximal rotation either left or right. Flexion is thought to lock out all vertebrae below allowing for rotation at C1-C2 only. The difficulty with the flexion-rotation test is maintaining flexion while maximally rotating the upper cervical spine. From my experience, there is a tendency to lose upper cervical flexion. In the residency, I learned that the flexion-rotation test assesses C1-C3. One can then differenciate C1-C2 restrictions from C2-C3 restrictions by first performing the side bend rotation test first, then performing the flexion rotation test. If greater rotation is achieved during the flexion-rotation test vs. the sidebend then rotation, it can be assumed the dysfunction is greater at C1-C2 joint.

It is important to understand that different programs teach different methods of assessment. One method is not better than the next as long as there is sound reasoning behind your decision making. Does anyone else assess C1-C2 differently or have preference with one method over the other? Let us know! -Jim Thank you to the Harris Health Orthopedic Residency for letting me use images from their Cervicothoracic Module Workbook.  I once had a teacher tell me, "A physical therapist is only as good as his/her home exercise program." At the time I did not fully understand the scope of this statement. Of course a home exercise program (HEP) is an essential component of physical therapy, but the really important aspects are completed in the clinic...or so I thought. Once I complete each initial evaluation, I start educating my patients on their HEP by giving them a frame of reference. I discuss how little time each week is spend with the physical therapist. If they come in 2 times a week for 45 minutes, they would not even be with me for 1% of the week. Getting better is a commitment that should require them to think about their HEP daily. Prescribing the correct exercises is another factor the must be considered of course. We want to combine the primary impairments found during the examination with results from any manual therapy to determine which exercises are most critical. While the patient is responsible for being committed to performing the HEP, it may be unrealistic to expect every patient to perform every exercise that we would prefer as clinicians, often leading to a selection of the most key exercises. I recently read a post from The Manual Therapist about the 5 articles that most significantly impact his practice (I highly recommend reviewing it). Several of the articles covered really had an impact on me regarding my understanding as to what my manual therapy techniques actually are and are not accomplishing. One of the articles is a basis for the differing views regarding Instrument Assisted Soft Tissue Mobilization (IASTM). IASTM techniques such as Graston and ASTYM preach the effect collagen remodeling, while other perspectives view it as a neurophysiological effect. One study showed that it requires over 100# of force to remodel fascia by 1% (Chaudhry et al, 2008). Why is it we spend so much time on soft tissue techniques and see results? Schleip did an extensive review on the fascial systems. He reminds the reader of the high number of mechanoreceptors located in the skin and other soft tissues. Different parts of the body are intricately connected via this fascial system, suggesting treatment of one location may impact another. When stimulated via our techniques such as soft tissue massage, trigger point release, foam rolling, etc., we are in fact encouraging the receptors to alter the sympathetic nervous system and alter tone in the muscle and fascia, which can be portrayed as a "release" in soft tissue restrictions. This leads us to believe that many of our manual therapy techniques achieve their results due to a neurological effect. To get mechanical changes, we would need high levels of force for prolonged periods (this may not apply to manipulations - high velocity low amplitude thrusts). If the fascia were as easy to deform as some think with manual therapy techniques, actions such as running, jumping, or even sitting provide larger forces than we are providing with our hands on our patients. Another study looked at spinal mobilizations/manipulations and their effect on various outcomes. Manual therapy techniques like these have been shown to have effects on the sympathetic nervous system via the dorsal peri-aqueductal matter of the midbrain (Hegedus et al, 2011). The study also found that these neurophysiological effects only last typically 5 minutes. They pain-modifying results lasted up to 24 hours. So what does all this mean? If we want any lasting changes, it is imperative we distribute a HEP that encourages movement in these gained patterns and establish the necessary changes in posture, habits, work space, etc. needed to reinforce proper tissue mobility and stability. It means our manual therapy techniques can be effective, but maybe not due to the reasons we previously thought. We can instill immediate or near-immediate changes with any manual therapy skills we have but they may not last more than anywhere from 5 minutes to 24 hours. To put it simply, manual therapy is not enough. Without an effective home exercise program, we would be likely to see our patients returning week after week with little retention of the gains we had achieved during prior treatment sessions. -Chris References:

Chaudhry H, Schleip R, Ji Z, Bukiet B, Maney M, & Findley T. (2008). Three-Dimensional Mathematical Model for Deformation of Human Fasciae in Manual Therapy. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2008;108(8):379-390. Web. 5 April 2014. Hegedus EJ, Goode A, Butler RJ, Slaven E. (2011). The neurophysiological effects of a single session of spinal joint mobilization: does the effect last? J Man Manip Ther. 2011 Aug;19(3):143-51. Web. 5 April 2014. Schleip R. (2003). Fascial Plasticity - A New Neurobiological Explanation. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2003;7(1-2):1-22. Web. 6 April 2014.  Next Tuesday I will presenting a Journal Club on the different manual physical therapy "cults" that exist in our practice. I did not choose the word "cult" nor do I think that this term is appropriate. "Cult" has a negative, even evil connotation, that makes the cult-ee seem close-minded and against all other practices. A simpler, more optimistic word may be "brand,"(which manual therapy brand is one associated with) but for the sake of today's writing, I will stick with cult. When discussing different manual cults, I think it is important to look back into the beginnings of this name game in PT practice. In a 1996 Physical Therapy Journal editorial entitled, "Be not content to Sleep and Feed," author James Holmes defends the "cult" of manual therapy against therapeutic exercise and passive modalities for the treatment of low back pain. Around this time, there was much controversy regarding the proper management of low back pain patients. Many patients were not improving with therapeutic exercise and the use of passive modalities. In response, some therapists turned to manual therapy. At this time, there was limited evidence toward the efficacy of manual therapy treatments. This change in practice did not go unforeseen. The traditional therapists started classifying manual therapy as a cult. In the editorial he writes: "reconsider chastising manual therapists as cultists...our methods await research validation...and our patients are better served as a result of the emergence of manual therapy." Holmes was right in defending manual therapy, but what is more interesting is that manual therapy in itself was viewed as a cult. Now each branch of manual therapy is its own cult: Maitland, Kaltenborn, Active Release Technique, IASTM, etc. As human beings, we have tendency to classify ourselves based on our training. The question one needs to ask, "is it bad to be identified with a certain brand of manual therapy?" I do not think so as long as I am not solely utilizing that one system. Each "cult" has its unique positives and negatives, but the truth is that our research is not strong enough to place a patient in only 1 cult. Be open-minded and ready for change. Humans are too unique and individual to place all of one's training into 1 type of practice. It is best to have an eclectic approach, where we consider evaluation and assessment techniques from various schools of though. -Jim Reference:

Holmes, James A (1996). Be Not Content to Sleep and Feed. Physical Therapy Journal. 76(6), 664-666. doi: 31 Mar 2014. |

Dr. Brian Schwabe's NEW Book in partner with PaleoHacks!

Learn residency-level content on our

Insider Access pages We value quality PT education & CEU's. Click the MedBridge logo below for TSPT savings!Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed